Editor’s note: The following sermon by Archbishop Richard Chenevix Trench is extracted from Great Sermons by Great Preachers (published 1889).

“Then Agrippa said unto Paul, Almost thou persuaded me to be a Christian.” — ACTS xxvi. 28.

Almost, and not quite! So near the prize, and yet missing it after all! With only one step between him and life, and that one step not taken! Surely this was a tragic doom; the whole range of Scripture does not offer us a more tragic one; for oh ! the difference between the ‘almost’ and the ‘altogether’ — a difference not less than between death and life, between all which we have most to fear, and all which we have most to desire.

Who was it that uttered these memorable words, which I take as they stand in our version, and without entering into the question whether or not they might be capable of a somewhat different turn? It was ‘King Agrippa,’ as St. Luke calls him; being known as Herod Agrippa the Second in profane history. It was no good stock of which he came. He was son of another Herod Agrippa, who is branded in an earlier chapter of the Acts as the murderer of James the Apostle; and who was only defeated by the interposition of an angel in his purpose of killing Peter also; of that Herod Agrippa who perished so miserably, being smitten of God in the hour of his blasphemous pride. Nor was this all. He was descended from a mightier criminal yet; he was great-grandson of that first Herod who slew all the young children at Bethlehem, trusting to include in that slaughter the royal Child, to whom the throne which he occupied as an intruder and usurper rightfully belonged. There was blood enough of God’s saints and servants on that wicked Herodian race; and, to do this Herod justice, there is no desire upon his part to shed more of this precious blood, or to curry favor with the Jewish people, by delivering Paul, as his father would fain have delivered Peter, to their will. Had he been such a cruel persecutor, breathing out rage and threatenings against the followers of Christ, his story would not have contained half, no, nor a hundredth part of the warning for us which it does contain. It might hardly have touched us at all.

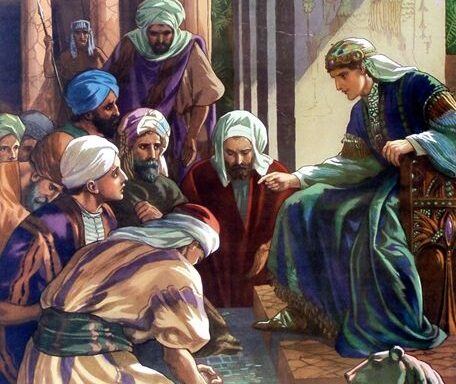

This Agrippa was a king — one of those little kings who were permitted to maintain a shadow of royalty within the limits of the Roman Empire. When Festus, the newly appointed Roman governor of the neighboring province, arrived at Caesarea, the seat of his government, it was consistent with the subordinate position of Agrippa, that he, though called a king, should do homage to the superior majesty of Rome in the person of the Roman deputy, and wait upon him on his first arrival, and welcome him there. After many days, spent no doubt in feasts and ceremonies and courtly revels, and when now the interest in these began to flag, and some new excitement was needed to stimulate the jaded appetite of these hunters after pleasure, Festus chanced to mention to his royal guest that a strange Jewish prisoner — his name was Paul — had been left upon his hands by his predecessor Felix. What offence this man had committed he was quite unable to make out; nor yet why the Jews were so fiercely set against him that nothing would satisfy them but his blood. And to confuse matters more, the man had claimed to be sent to Rome, and to be tried before the Emperor himself, a right which, being a Roman citizen, could not be denied him; while yet he, Festus, was sorely perplexed what account of Paul’s matters, of the crime wherewith he was charged, to send with him. In fact, the whole quarrel between the other Jews and this Paul was a mystery to him. It turned on some wretched dispute of their own superstition, on one Jesus, who certainly was dead, for a predecessor of his own, Pontius Pilate, had crucified him some thirty years before; but whom Paul, who on other points seemed reasonable enough, persisted in affirming to be alive.

The curiosity, perhaps even the interest, of Agrippa is excited. Though not a Jew by birth, he was such by education; familiar with the law and the prophets, ‘expert in all customs and questions which were among the Jews.’ He would gladly hear the man himself. Festus readily consents. It was this probably which he had been aiming at all the while. The next day they are all assembled: Agrippa and Bernice ‘with much pomp,’ and Paul with his chain. But being permitted to speak for himself, he so speaks, so convincingly, with such demonstration of the truth, so pressing home upon the king the claims of Jesus of Nazareth to be the Christ, the promised king of Israel, that from Agrippa at length are wrung those memorable words, ‘Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian.’

But wherefore ‘almost,’ and why not altogether? How came it that he stopped short where he did, and never advanced any further? Alas! brethren, it is only too easy to answer this question. Our own hearts supply, and only too well, the answer, when they whisper to us that, under like temptations, we might only too probably have stopped short where Agrippa stopped. For suppose he had been ‘altogether’ persuaded. What a change in all his outward conditions of existence must have followed! What a coming down from his pride of place!

To be a Christian was not so easy a thing then as it is now. No more of that great pomp, no more of those obsequious crowds, no more of that royal purple, no more of those flatteries and favors which the world reserves for its own, for the great and prosperous among its own children. Then too, if the king was bound, as there is too much reason to believe, in the cords of an unholiest attachment, those cords must have been snapt asunder at once, that secret wickedness utterly put away. And other thoughts, as we can little doubt, rose up before him, even the thoughts of all the scorn and all the bitter mockery which that same world has in store for those that desert its allegiance.

What would they say at Rome? What would they say at Jerusalem? What would they say in Caesar’s palace; what in the Great Sanhedrim, when it was told, as the latest and most piquant news of the day, that he, that King Agrippa, had thrown in his lot with the despised Nazarene, the crucified Galilean? All this, we may well believe, passed swiftly through his mind; he counted the cost, and that cost seemed too much for him to pay.

Truly, dear friends, it was much; the only question is, whether it was too much. Perhaps not. Perhaps he counted amiss, and another could have counted better for him than he counted for himself. Let us make the experiment. Let us, for we can do it deliberately and dispassionately, cast up his gains first, and then his losses, and set those against these. His gains, what were they? For a few years more he kept the glories to which he clung, he played his part of king on the world’s stage, and men bowed to him the crooked hinges of the knee, and paid him lip-homage, and he sat in the chief place of honor at wearisome feasts, and was the principal figure in hollow court-ceremonials and empty pageants of state; and then the play was over, and his little day was done, and darkness and night swallowed up all, and he carried nothing away with him when he died (except indeed his sins), neither did his pomp follow him. His gains then, they were not after all so very large, and, such as they were, they did not tarry with him long.

But his losses, or rather his loss? It may not seem so much, seeing that it can be summed up in a single word, and yet that word a word of awful significance. What did he lose? He lost himself. Christ has demanded, ‘What shall a man profit, if he gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?’ Agrippa had not gained the whole world — only a miserable little fragment of it; and this but for a moment, for a little inch of time; but in the grasping and gaining of this he had made that terrible loss and ship wreck of which Christ speaks, had lost himself; in other words, had lost all.

But now let us contemplate the matter from another point of view.

Suppose, dear brethren, he had found strength actually to do that thing which he was almost persuaded to do; suppose he had made room for the truth in his heart, had been wholly persuaded to become a Christian, had followed on where the Spirit would have led him, how would it have been with him then? Here, again, let us count the cost for him; let us put the sufferings of this present time over against the eternal weight of glory. The sufferings of this present time — a few years of self-denial and of toil; a few hard words and contemptuous looks from the world which he had forsaken, a few buffetings from evil men; it might have been a sharp and painful passage into life; but sweetened all by the sense of God’s love, by the assurance of His favor, by the knowledge of sin forgiven, of a conscience cleansed from its guilty stains through the blood of the atonement, by the fellowship of all the best and noblest upon earth, by the hope of a glory to be revealed; and then, this brief life ended, then when the expectation of the worldling perishes, when there is nothing more for him but a fearful looking for of judgment to come, Agrippa’s hope would have begun to find its fulfilment, and the gates of Paradise have been thrown open to him, and the great ‘Well done’ have sounded in his ears. For the purple which here he renounced, he should have been clothed for ever in the white and shining garments of immortality; for the crown which here he laid down, he should have worn a crown of life for evermore. Joy beyond joy, to see the face of God, and in and through that beatific vision to be changed from glory to glory even into His likeness, to leave behind and for ever every soil and spot and stain, all impurity and defilement; and this should have been his portion for ever. Certainly it was a mistake which he made, a miscalculation, as we all must own. It was a rich treasure hid in the field, on which he had stumbled unawares. It was a pearl of great price, which had come within his reach, and he would have been no foolish merchantman had he sold all that he had, and bought this pearl. It would have proved no sorry bargain after all.

We own, we confess as much. Standing, in regard of him, upon an eminence, where the hillocks of time do not conceal from us the mountains of eternity, nor the trivialities of this life the realities of the life eternal, as for him they did, we are all ready to admit that he left the better part, and chose the worse; even while we do not conceal from ourselves the mighty difficulties which hindered him from embracing that better. But shall we stop here, with this acknowledgement? Are not all things, and these among the rest, written for our learning? What about ourselves? Are there no Agrippas now? Thou that art hesitating in thy mind, thou also convinced of sin by the power of the Spirit, but not yet converted from sin by the same Spirit, thou that tremblest on the brink of the mighty river of God’s love, and yet darest not commit thyself boldly to its waves, art not thou exactly such another as this was? Change the name and this tale might be told of thee. Thou art this King Agrippa; thou art the man. Thou too hast said after some searching sermon, or the earnest converse of some godly friend, or after reading some holy book which has found thee out in the deeper depths of thy soul, or after some manifest dealings of God with thee by sorrow or by joy, by mercy or by judgment, thou too hast said to this book, to this sermon, to this friend, to this joy, to this sorrow, or rather to Him who was speaking to thee through all these — ‘Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian, a Christian in deed and not only in name, to accept Christ for what He is, the true Lord of my life;’ and yet this ‘almost’ of thine, like that of the unhappy king long ago, has never ripened into a ‘quite.’

And why not? It rises clear before thee, the blessedness of a life in Christ, of having the deep wound of thy spirit healed, as He only can heal it, of throwing in thy lot with saints and apostles and martyrs, and all the holy and humble men of heart that have ever lived, of working for God, and not against Him, for the truth and not against it, the blessedness of such a life as this rises up plainly before thee; and the emptiness, the vanity, the disappointment, the defeat, the misery, the despair which must attend any other life than this; and thou too hast almost chosen thy part, even that better part which should never be taken from thee. And why not? what has hindered? what has stood hitherto in the way of so blessed a consummation? will perhaps stand in the way unto the end ? Alas! exactly that which stood in the way of King Agrippa. The bands that bound him, and bound him so closely, that he dallied indeed with life and with heaven, but made a covenant with death and with hell, they are the same that bind thee.

Perhaps, like him, thou art holden by the cords of some sinful passion. Thou canst not bring thyself to forego the sweetness of it. It seems to thee that if that were taken out of thy life, the life which remained would not be worth the living, that all the wine would be drawn, and nothing but the lees remain. Or the sin may not be sweet, the sweetness of it, if it ever had any, may have departed long ago; — but though not sweet, it may be strong, binding thee with bands which thou hast no courage to break, which thou knowest thou couldst not break with out a far mightier effort than any which thou art prepared to make.

Or there may be no such single well-defined hindrance to thy yielding thyself without reserve to that God, who would have thee altogether, that He might bless thee altogether; no bosom sin, dear as a right eye, almost as much a part of thyself as a right hand, which would need to be plucked out or cut off; but rather a more vague and general reluctance to yield thy will to God’s to mortify the corrupt affections of the heart, and to come under the rules and discipline and obligations of the life in Christ, the indolence of a worldly and self-indulgent spirit, than which perhaps there is nothing more effectual to keep men from Him. Or it may be, at least in part, the fear of man which oppresses thee.

What will they say, the old ungodly companions with whom thou hast walked at liberty in times past, when thou announcest to these thy intention of ordering thy life henceforward by another rule, of living the rest of thy time not to the lusts of men but to the will of God?

But be these bonds what they may, oh! believe that it is worth the while to break them, as in the strength of Christ they can be broken. These mountains of opposition, it is worth while to cry to Him, that He would make them a plain. It is well worth the while. A few years hence, and it will be with every one of us, as it was with King Agrippa not very long after these memorable words were uttered; and then how utterly insignificant, not merely to others but to ourselves it will be, whether we were here in high place or in low, rich or poor, talked about or obscure, whether we trod lonely paths, or were grouped in joyful households of love; whether our faces were oftener soiled with tears or drest in smiles. But for us, gathered as we then shall be within the veil, and waiting for the judgment of the great day, one thing shall have attained an awful significance, shall stand out alone, as the final question, the only surviving question of our lives, Were we almost Christ’s or altogether, in other words, were we Christ’s or were we not?

Oh! sadness of all sadnesses — that ‘almost,’ which never ripened into ‘quite’; to have stood on the brink of the great river of salvation, and yet never to have committed ourselves to its waves; to have seen the King afar off, some faint glimpses of His beauty, and yet never to have followed on to know Him more, and thus never to see Him near. Oh ! sadness of all sadnesses, and guilt of all guilts! And that this may be never ours, let us pray earnestly and with something such a prayer as this: ‘Fix, Lord, our wavering hearts on Thee. Strengthen our weak desires for Thee. Suffer us not to fall back from Thee, even though we would. Hedge up our way behind us, though this be with thorns. Draw us to Thyself, and having drawn, bind us by any cords to the horns of thy altar. Compel us by any discipline of love, that we be not almost, but altogether, Thine.’

5