Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twenty-third chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

(Go back to previous chapter)

CHAPTER XXIII

On resuming our journey, we had not proceeded a couple of miles, when on cresting a rise we came in sight of the Salisbury relief force coming out of the bush ahead of us and just entering the valley which lay between us. The two columns were soon laagered up in the open ground some 500 yards apart on either side of a small stream. With the Salisbury contingent were Mr. Cecil Rhodes, Sir Charles Metcalfe, and several gentlemen who, having left Bulawayo on a shooting trip some two months previously, had been obliged on the outbreak of the rebellion to take refuge in the Gwelo laager, where they had been cooped up ever since.

Mr. Rhodes, I thought, looked remarkably well, and yet the fast grizzling hair and a certain look in the strong face told the tale of the excessive mental strain undergone during the last few months. Amongst those who had joined the Salisbury column at Gwelo were Mr. Weston Jarvis, Mr. Farquhar, the Hon. Tatton Egerton (M.P. for Knutsford) and his son. That evening Mr. Rhodes and Colonel Napier dined with our mess, and in course of conversation after dinner it was decided that, instead of returning at once with the combined columns along the main road to Bulawayo, a flying column should be sent under Colonel Spreckley through the country to the south of the hills bordering the Insiza river, whilst Colonel Napier should travel down the valley of that river itself with the main body; the two columns to meet in the neighbourhood of the ford across the Insiza, on the road from Bulawayo to Belingwe.

Early on the morning of Thursday, 21st May, Colonel Spreckley’s column of about four hundred men left us and bore away to the south; the main body to which my own troop was attached making a move very shortly afterwards. We first kept the road as far as the valley beyond the Pongo store, but there turned off to the south, outspanning at about eleven o’clock amongst a lot of kraals, all of which had evidently been hastily vacated on our approach, as they were all full of grain, and pots were found cooking on fires that had only lately been lighted. The corn-bins in these villages were one and all quite full of maize, Kafir corn, and ground-nuts, showing not only that the harvest in this part of Matabeleland had been a very plentiful one, but also that the people thought they had got rid of the white men for good and all and had no reason to fear their return.

After all the grain had been removed that we could carry, the kraals were burnt and the remainder of the corn destroyed, in order that it might not again fall into the hands of the rebels, for a good food-supply constitutes “the sinews of war” to a savage people, who are not likely to come to terms as long as such supplies hold out.

In the afternoon we moved on a few miles farther, destroying several more kraals. The huts in some of these had been newly built and plastered, and we found that ground had been freshly hoed up to lie fallow until the sowing-time came. In every village were found goods of some kind or another which had belonged to the many white people murdered in this district, and the articles of women’s clothing, and especially a hat that was recognised as having belonged to a young girl of the name of Agnes Kirk, made the troopers simply mad to exact vengeance on the murderers.

About two miles distant from the spot where we laagered up for the night, the huts of some white prospectors were found, but no trace of their former owners. These huts had been made use of by the Kafirs as store-rooms, and were found to be full of every conceivable description of merchandise, taken from neighbouring farmhouses and the hotels and stores along the road. The goods were all carefully packed up, and included bags of sugar, flour, and Boer meal, as well as boxes of soap and candles, tinned provisions, blankets, and many other articles. Outside the huts stood a waggon and a coach, the latter of which was known to have been brought from the Tekwe store, some five miles distant.

As it was evident that we were now in the midst of a native population, who were not only responsible for the murders of the white men in the district, the destruction of their homes, and the looting of their property, but who also seemed so infatuated by their success that they appeared to think that the compatriots of the murdered people “would never come back no more,” it was determined to make an effort to prove to them in a practical manner that there is some truth in the French proverb which says that “tout vient à qui sait attendre.”

Therefore at 4 A.M. on the following morning, the 22nd May, Grey’s Scouts and a portion of the Africander Corps under Captain Van Niekerk, in all about one hundred men, were sent out down the valley of the Insiza in order to try and discover the whereabouts of the main body of the rebels in this part of the country. The members of the patrol at first proceeded on foot, leading their horses until day broke, when the order was given to mount. Shortly afterwards smoke was seen rising from a valley amongst the hills to the left, and the horses’ heads were at once turned in that direction, and presently, after the first range of hills which bounds the Insiza valley had been passed, a herd of cattle was seen amongst the broken country on ahead. These cattle were found to be in charge of a small force of Kafirs, who abandoned them to the white men without making much resistance.

It was the firing which took place during this skirmish which was heard in camp soon after sunrise, and which caused Colonel Napier to send Commandant Van Rensberg and myself with a small party to ascertain what was going on. Just after these cattle had been captured, Mr. Little and some of Gifford’s Horse under Captain Fynn, forming the right-hand flanking party to Colonel Spreckley’s column, which was then moving forwards some four miles to the south, rode up, having been attracted by the firing. After a few minutes’ conversation, no more Kafirs being anywhere in sight, Colonel Spreckley’s men went on their way, whilst the Scouts and Africanders started on their return with the captured cattle towards the laager. A little farther on a halt was made, and some of the men produced some provisions from their wallets and were proceeding to discuss the same, when Kafirs were suddenly seen on the crest of a rise in front.

At this moment Captain Grey was missing, but he turned up immediately afterwards with seven of the Scouts, who had been foraging with him, each man having a dead sheep tied behind his saddle. These, however, had to be immediately cut loose and abandoned, as large numbers of Kafirs were now seen both in front and to the right, where they had previously been hidden in a deep river-bed.

A running fight was now commenced, which was kept up for some four miles before the Kafirs were shaken off. When it was first seen that the Matabele were in force, and meant to try and cut off their enemy’s retreat, Captain Grey sent the American Scout Burnham, together with a compatriot named Blick, to the top of a hill on ahead, to try and ascertain the numbers and disposition of the rebels; but Burnham and his companion were cut off from the main body, and had to gallop for their lives, and had they not both been very well mounted, they would probably not have got away, as the Kafirs nearly surrounded them in a very rocky bit of ground. The cattle which had been captured had to be abandoned by the men who were driving them, and very hurriedly too, as a party of the rebels made a determined attempt to cut them off from the main body.

Early in the fight Trooper Rothman of the Africanders was shot through the stomach, and, as a comrade named Parker belonging to the same corps was assisting the wounded man to mount his horse, he was himself shot through the upper part of the body, from side to side, and died almost immediately. Poor Parker had to be left where he fell, as there was no means of carrying him.

Just as the white men were descending the last hill-slope into the level valley of the Insiza river, a young Dutchman named Frikky Greeff, the son of an old elephant-hunter long resident in Matabeleland, had his horse shot through both forelegs just above the fetlocks. On being struck the poor animal fell heavily, pinning its rider to the ground. He, however, soon extricated himself, and one of the Scouts, Trooper Button, who was riding a strong, quiet horse, took him up behind him. Up to this time poor Rothman had been able to retain his seat on his horse, but being greatly weakened by loss of blood, and in fact in a dying condition, he now fell off. Lieutenant Sinclair of the Africander Corps, on seeing this, dismounted, and with the assistance of others placed Rothman across his saddle, and, mounting behind him, carried him in this way for over three miles. By this time it was apparent to all that the man was dead, so, as the Kafirs had now given up the pursuit, the body was placed on the ground in a shady place, there to remain until it could be recovered and brought in to camp.

After getting out into the open country the horses were off-saddled for an hour on the banks of a stream which runs into the Insiza, and the patrol then returned to laager. Besides the two men who were killed, two more were wounded, though not seriously, Trooper Niemand being shot through the fleshy part of the arm, and Trooper Geldenhuis getting something more than a graze just above his ankle. Singularly enough, as all the men were mixed up together, all the casualties occurred to members of the Africander Corps.

Just at sunrise the same morning Colonel Napier asked me to take a few mounted men of the Salisbury column and proceed, together with a small detachment of the Africander Corps under Commandant Van Rensberg, to a ridge of hills on our left rear, in order to burn some kraals which could be seen with the glasses in that direction.

We were just getting ready to start, when shots were heard straight ahead of us down the Insiza valley; and as the firing, though never very heavy, was kept up until our horses were all saddled up, Van Rensberg and myself asked permission to take our men in the direction of the firing, as we knew that it meant that Captains Grey and Van Niekerk were engaged with a party of Matabele, and we thought that we might be able to render them some assistance.

Colonel Napier at once granted us permission to do as we wished; so we lost no time in making a move, and before we had ridden much more than a mile heard two shots at no great distance on our left front. We immediately turned in that direction, and after having crossed a small stream, again heard two more shots which sounded quite close, in fact, only just beyond a ridge of low stony hills on our left. On hearing these shots we rode to the crest of the ridge as quickly as possible, and then saw a broad open valley beyond us, in the centre of which stood a good-sized native kraal. We however could see nothing, either of our friends or our enemies, nor did we hear any further shots. We therefore crossed the ridge, and a deep river-bed beyond it, and rode towards the kraal, with the intention of burning it. Before reaching it, however, we caught sight of a few natives running through some corn stubble, and galloping after them found them to be a young woman and three little girls. These were taken prisoners and sent back to camp, as it was thought that Colonel Napier might be able to obtain some information from them regarding the whereabouts of any impis that might be about.

Just then a man carrying a shield and assegais was seen running to our right. He was soon caught and shot by some of the Africanders, just as he threw himself under a bush, where he then lay on his face, dead. “Pull him out that I may look on the murderer’s face,” I said in Dutch to the men, which they did, revealing the features of a middle-aged evil-looking Kafir, whom, however, I did not remember to have ever seen before.

After killing this man we rode back towards the kraal, but before reaching it, made out a number of Matabele standing on the slope of a hill overlooking a deep river-bed, about a mile distant. On looking at these natives through the glasses, I could see that they were all men, many carrying shields, and as there were too many of them to make it possible to suppose that they all belonged to the kraal near which we were standing, I surmised that they probably belonged to the impi with which Captains Grey and Van Niekerk had been engaged.

Not knowing their numbers, and recognising the impossibility of getting at them in the hills with mounted men, Van Rensberg and myself judged it advisable to send back to the laager for a reinforcement of men on foot. A man was therefore at once despatched with a verbal message to Colonel Napier, and whilst waiting for his return we took up our position on the crest of the rise we had previously crossed, in order both to guard against a surprise and keep a watch on the enemy. These latter gradually retired round the shoulder of the hill and disappeared from view.

From where we had taken up our position we could see the laager, which was little more than a mile distant, and the reinforcement of footmen we had asked for had already left it, when a heavy fusillade broke out which sounded amongst the hills to our left front. Immediately after this heavy firing commenced, large numbers of Matabele, who up to that moment had been hidden in the river-bed below the hill on which we had seen the others standing, suddenly showed themselves, and streamed out across a corn-field with the evident intention of taking part in the fight which it seemed was going on between the Scouts and Africanders under Captains Grey and Van Niekerk and another body of Matabele. Our party consisted of only twenty-two men all told, and it was rather difficult to know what was the best course for us to pursue; but we had just decided to go on and try and reach our friends without waiting for the reinforcements, when the heavy firing ceased, being succeeded by scattered shots, which showed that the fight was moving more and more to the right. The Matabele whom we had seen leaving the shelter of the river-bed must also have recognised this fact, as they soon returned, marching in lines across the corn-field where we had first seen them, and again taking up their old position.

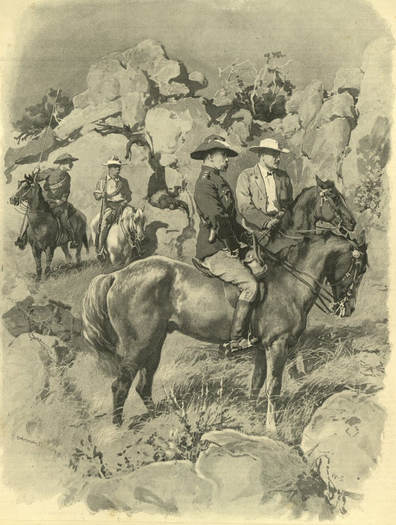

Shortly after this Captain Windley and Lieutenant Frost came up with thirty Colonial Boys, and Captain Taylor and Lieutenant Jackson also brought a contingent of Friendly Matabele; but as but few of these latter were armed with rifles, they could not be expected to be very useful in attacking a position, though no doubt they would have done excellent service in following up a defeated foe. Mr. Cecil Rhodes, Sir Charles Metcalfe, Mr. Weston Jarvis, and Lieutenant Howard also came up with the Colonial Boys.

On their arrival we at once proceeded as quickly as possible towards the point in the hills from which the heavy firing had seemed to come, and after having advanced for about a mile and a half through thick thorn bush we found ourselves in a valley bounded on one side by the main range of hills, and on the other by a single hill very thickly wooded at the crest. At this point several natives were seen on the hills above us to the left, and a few shots were fired at them, which they returned, whilst at the same time some shots were also fired at us from the crest of the rise to our right. I therefore ordered the Colonial Boys to charge up the hill and take it, which they at once did, led by their officers and Lieutenant Howard; the few natives who had been firing from the summit at once giving up their position, and running down into the thick bush on the farther side, several of them leaving blankets and other goods behind them, whilst in one case a handkerchief had been abandoned, which was found to contain about twenty Martini-Henry cartridges. After we had taken possession of the hill, a few odd Matabele fired a shot or two at us from the valley below and from the hills above, but their fire was soon silenced by the heavy fusillade kept up by the Colonial Boys.

From the position we had taken we commanded a good view over the country to our front and right front, but we could see nothing of the mounted men under Captains Grey and Van Niekerk, and therefore judged that they had found it necessary to retreat from the Matabele by a circuitous route to the laager; and we soon saw that it would be expedient for us to do the same, as we could see a large number of rebels on a hill about 1000 yards to our right, amongst them being a man on horseback, and knew that besides those actually in sight there were many others in the river-bed under the hill, as well as the impi which had been engaged with the Scouts and Africanders, which we afterwards discovered was lying in a deep river-bed hidden from view only a short distance ahead of the hill on which we were standing.

In the valley beyond this river-bed were two small herds of cattle in a corn-field, but this seemed such a very obvious bait to entice us onwards that Van Rensberg and myself at once saw the advisability of getting back to the more open country beyond the thick thorn bush through which we had come as quickly as possible, in order not to allow ourselves to be outflanked by the impi to our right, which had now disappeared in the bush behind the hill on which we had seen it.

Had we crossed the river-bed in front of us and endeavoured to capture the cattle, we should have been completely cut off from the laager by two separate impis, which our small force would have been altogether inadequate to cope with. By keeping well to the right, however, on our return to the open country we avoided coming in contact with the enemy in the bush, and saw nothing more of them.