Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twenty-fourth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXIV

On reaching the laager, Van Rensberg and myself, backed by Mr. Cecil Rhodes, were very anxious to have the base camp moved at once to the kraal near to which we had captured the woman in the early morning, and then at once attack the impis we had seen that same afternoon with as large a force as could be spared from the laager. However, as Captains Grey and Van Niekerk had then not yet returned, Colonel Napier thought it would be better to move the laager round the hills to the vicinity of the Insiza river and attack the rebels from that side on the following day.

This plan was at once acted upon, and the Scouts and Africanders turning up just as we had inspanned, we moved round the broken country in which the Matabele had taken up their positions, and camped in open ground beyond it, on a small stream running into the Insiza river.

Early the following morning we moved to the bank of the river itself, just opposite the spot where a Dutchman named Fourie had been building a house for a Mr. Ross, whose temporary residence whilst the house was being built could be seen still standing on a rise some mile and a half farther down the river.

At the latter end of March Mr. Fourie had been living here with his wife and six children, whilst Mr. and Mrs. Ross with an adopted daughter named Agnes Kirk were occupying temporary dwellings some little distance away from them. These eleven people—two men and nine women and children—were all murdered on the outbreak of the rebellion, Miss Johanna Ross being the only survivor of her family, and owing her escape to the fact that at the time the murders were committed she was on a visit to friends living near the main road, who, having received warning of the rising, took her with them to Mr. Stewart’s store at the Tekwe river, where they were relieved by Captain Grey and his men on Thursday, 26th March.

With others I went down to the scene of the massacre of the Fourie family early in the morning and found the remains of four people—a woman and three children, the body of Mr. Fourie and those of three of the children being missing. The murders had evidently been committed with knob-kerries and axes, as the skulls of all these poor people had been very much shattered. The remains had been much pulled about by dogs or jackals, but the long fair hair of the young Dutch girls was still intact, and it is needless to say that these blood-stained tresses awoke the most bitter wrath in the hearts of all who looked upon them, Englishmen and Dutchmen alike vowing a pitiless vengeance against the whole Matabele race.

At about ten o’clock a force of about 300 men under Captain Grey was despatched to the scene of yesterday’s fighting, Colonel Napier and staff taking up a position with a seven-pounder gun on the top of a hill which commanded the valley in which we had seen the two small herds of cattle on the preceding day. I was placed in charge of the infantry division, which, spread out in skirmishing order, formed the centre of the line of attack.

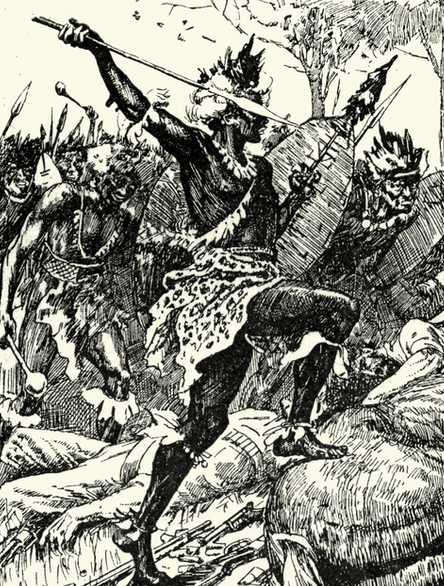

After what had been seen that morning of the ghastly remains of the Fourie family, every one was most eager to come to close quarters with the Kafirs, but we were not able to do so, as, although we found the scherms where they had slept, with the fires still burning in them, the impis had left apparently at daylight in the morning, and it was impossible to tell in which direction they had gone, as their camp was surrounded by rough stony hills, on which their footsteps had left no trace. As the number of their scherms showed that the rebels must have been at least a thousand strong, I don’t quite know why they did not wait for us and have another day’s fighting, the more especially as they had been successful in repulsing about one hundred mounted men of the Scouts and Africanders on the previous day. I am half inclined to think that several rocket signals sent up from our laager during the early part of the preceding night, to notify our whereabouts to Colonel Spreckley, may have had something to do with their unexpected retreat, or possibly a peep at our laager at daylight may have given them an exaggerated idea of our numbers. At any rate they were gone, and the blow which might have been struck at them on the afternoon of the day before was now not struck at all.

On the site of the engagement of the previous morning between Grey’s Scouts and the Africanders and the one section of the Matabele, we found the body of Parker, absolutely stripped of clothing, even to the socks, and riddled with assegai stabs inflicted after death. The corpse was carried back to camp, together with that of Rothman, which latter, as it had been carried to some distance from the scene of the fight, had not been found and mutilated by the Kafirs. The Matabele must have removed their dead, as none were lying on the hill-side below Parker’s corpse, where many had been seen to fall. However, in a small kraal situated just under the hills and within a mile of the scene of the fight, we found a Kafir lying stretched out on his back close to the door of a hut, who could not long have been dead, as his body was still warm, and his limbs quite limp. He had evidently been wounded during the fight, the bullet having passed through both thighs, and broken the right femur. Then I suppose he had been carried or had crawled to the village where we found him lying, and a cord tightly twisted round his neck showed that he had been strangled shortly before our arrival on the scene. Whether he had thus compassed his own death on hearing or being informed of our approach, or whether he had been strangled by a friend to prevent his falling into the hands of the white men, I cannot say, but as, besides having been strangled, he had a fresh assegai-wound in the right side, I fancy that he had been killed by his friends, who had fled at our approach and were unable to carry the wounded man with them.

Besides this man, another was found in a dying condition—a young fellow of two or three and twenty who must have been some one of importance, as his friends had made a stretcher of oxhide lashed to poles, on which to carry him. They seem to have been surprised in the act of carrying him away, as the stretcher was first found, and then the wounded man was seen crawling away at a little distance, but he was nearly spent, having been shot right through the chest, and died soon afterwards. His shield and assegais, and many little personal belongings, were found tied on to the stretcher.

After having burnt a few kraals and picked up a flock of sheep and goats and a stray cow or two, we returned to laager very much disappointed that we had had a ten-mile walk for nothing, so far as meeting with the rebels was concerned. The Hon. Tatton Egerton (M.P. for Knutsford) accompanied us on this outing, walking and shouldering a rifle with the rest of us, and unless I am very much mistaken no one was more eager to let off his piece at a Kafir than was he. In the afternoon a military funeral was accorded to the bodies of Parker and Rothman, and also to the poor scattered remains of the Fourie family, which having been carefully collected were all buried in one grave dug close alongside that in which the two dead troopers had been placed. The funeral service was read by the Rev. Douglas Pelly, who was attached to the Salisbury contingent.

After the service was over I took a few men of the Africander Corps, and some friendly Matabele with a stretcher, and went off to collect the remains of the Ross family. These we found had been scattered and dragged about in every direction by dogs or wild animals. We could find no trace of Mr. Ross, and it is quite possible that he had been murdered at some distance from his homestead. The broken skull of a young woman which we found close to the door of one of the huts must have been that of Miss Agnes Kirk, but of old Mrs. Ross all we found by which to identify her was a mass of long grey hair, the skull having disappeared. Besides these sad relics we also found the remains of three children, the one a boy by his clothes, and the other two, little girls, their fair hair being still plaited into several short plaits in the Boer style. These three poor children must have been members of the Fourie family who had probably been visiting the Rosses on the day when the murders were committed.

Thus, of the eleven people murdered here some remains of all were found, except of Mr. Fourie and Mr. Ross, and these being the only men were very likely led away on some pretext, such as looking at cattle, and murdered at a distance from their dwellings where there was no chance of their getting hold of rifles or revolvers. Then, the men being disposed of, the noble savages came down fearlessly to the homesteads and smashed in the heads of the women and children comfortably and at their leisure.

On Sunday, 24th May—the Queen’s Birthday—we continued our march down the Insiza valley, burning a large number of kraals as we advanced. All these kraals had only just been deserted by their owners, and they were all full of grain, while, in addition, in every one were found articles of some kind or another which had been taken from the homesteads of white men. All the grain that could not be carried with us was destroyed as far as possible. In many of the kraals were found large accumulations of dried meat, and many dried skins of bullocks, cows and calves, proving that the rinderpest had been brought into this district by the natives since the outbreak of the rebellion, and had been playing havoc amongst their cattle.

As we advanced, burning kraal after kraal, on the northern slope of the range which runs to the south of and parallel to the course of the Insiza river, column after column of smoke continually ascending into the clear sky from the southern side of the hills let us know that Colonel Spreckley’s column was devastating the murderers’ country on his line of march as effectually as we were doing on ours.

On the following day we still pursued our way unopposed down the Insiza valley, burning kraal after kraal, but never seeing a sign of the native inhabitants, who had evidently received timely notice of our approach and fled into the hills. On the morning of Wednesday, 27th May, we reached the Belingwe road at about nine o’clock, and were soon joined by Colonel Spreckley’s column which had been waiting for us a little farther down the road. Colonel Spreckley’s force had had no general engagement with the enemy, but his scouts had captured about seven hundred head of cattle and twenty-three donkeys. They had also found the remains of several murdered Europeans, amongst whom the bodies of a miner named Gracey and those of Dr. and Mrs. Langford and a Mr. Lemon were recognised. Mr. Gracey’s body lay just outside his hut, but he had evidently been killed when lying on his bed inside, as a blanket still lying there was soaked through and through with blood.

The case of Dr. and Mrs. Langford is one of the saddest of the many sad episodes of the late native insurrection in Matabeleland. They had been married but a short time, and had only left the old country three months before the rebellion broke out. Unfortunately fate ordained that they should reach Bulawayo, and leave it in order to take up their residence in the Insiza district, just before the outbreak. Thus they were suddenly surprised by a party of murderous savages when travelling in their waggon. Mr. Lemon was with them, and his body was found lying close to that of Dr. Langford; but poor Mrs. Langford’s corpse was discovered some two miles away under the bank of a stream flowing a few hundred yards below Mr. Rixon’s farmstead. It looked as if when first attacked the two men had held the murderers at bay, and given Mrs. Langford time to run on to Mr. Rixon’s house in the hope of obtaining assistance. But when she reached the homestead she found it unoccupied, Mr. Rixon having left the day before. The poor woman then probably waited at the house for the husband and friend that never came, and then knowing that they must have been killed took refuge under the bank of the river which ran below the house. Here she seems to have lain hidden for some days at least, as she had made a sort of bed of dry grass to lie on under the bank, and as a pie-dish was found beside her body, she probably visited the house at nights to get food of some sort. The agony of mind this poor young woman must have suffered, one shudders to think of. But at last the Kafirs found her, and then, poor soul, her troubles were nearly at an end, for they lost no time in killing her. They appear to have stoned her to death, as her skull was terribly shattered and some large round stones taken from the river-bed were lying beside her corpse. None of her clothes had been removed, and two rings were still on her finger, on the inner side of one of which were engraved the words “Sunny Curls, Mizpah.”

On the afternoon of the day on which the columns rejoined, the Insiza river was recrossed by the ford on the main road leading from Belingwe to Bulawayo, and on the following day, 27th May, the Salisbury contingent, reinforced by sixty men of Gifford’s Horse, left the Bulawayo column, and went off southwards with the intention of visiting the Filibusi district, where it was thought that an impi might be met with, and thence making their way to Bulawayo by the road which passes Edkins’ store, where it may be remembered a number of white men were murdered at the first outbreak of the insurrection. As soon as the flying column under Colonel Beal had left us, Colonel Napier gave the word to inspan, and an hour later the remainder of the troops under his command were on their way back to the capital of Matabeleland, which was finally reached after an uneventful journey on Sunday, 31st May.

As on the road home the column passed near the northern boundary of my Company’s property of Essexvale, I asked and obtained leave from Colonel Napier to pay a visit in company with Mr. Blöcker to the homestead where I had been living in the midst of an apparently happy and contented native population at the outbreak of the insurrection. Leaving the camp at daylight, just as the mules were being inspanned for the morning’s trek, we reached the scene of our agricultural labours after a two hours’ ride, only to find that the house was absolutely gone, literally burnt to ashes, there being nothing left to mark the spot on which our pretty cottage had once stood but the stone pillars and solid iron shoes on which it had rested. The roof of the stable had been burnt too, as well as all the outhouses, and a waggon, under which last wood must have been piled in order to set it alight. The only building which had not been destroyed was the kitchen, which, having been built very solidly of stone with an iron roof, was practically fireproof. The mowing machine and rake had not been touched, nor had the ploughs been interfered with. In the vegetable garden we found any amount of cabbages, cauliflowers, onions, carrots, parsnips, beetroot, tomatoes, etc., which had ripened since the natives had left, and we loaded up our horses with as much as they could carry. The potatoes had all been dug up by some animals, probably porcupines. We visited some of the native villages close round the homestead, but found them entirely empty, having been probably deserted since the time when the Matabele burnt my house down. After having off-saddled our horses for a short time, we rode back with our load of vegetables to the column, which we found laagered up some six miles farther along the road than where we had left it in the morning.