Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Essays on History and Literature, by James Anthony Froude (published 1906). All spelling is in the original.

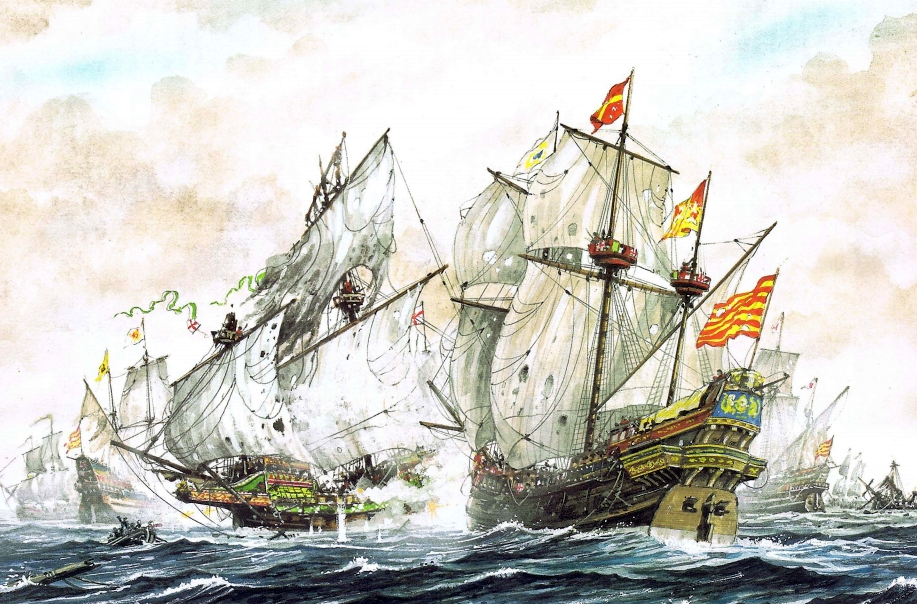

In August, 1591, Lord Thomas Howard, with six English line-of-battle ships, six victuallers, and two or three pinnaces, were lying at anchor under the Island of Florez. Light in ballast and short of water, with half their men disabled by sickness, they were unable to pursue the aggressive purpose on which they had been sent out. Several of the ships’ crews were on shore: the ships themselves “all pestered and rommaging,” with everything out of order. In this condition they were surprised by a Spanish fleet consisting of 53 men-of-war. Eleven out of the twelve English ships obeyed the signal of the Admiral, to cut or weigh their anchors and escape as they might. The twelfth, the Revenge, was unable for the moment to follow; of her crew of 190, 90 being sick on shore, and, from the position of the ship, there was some delay and difficulty in getting them on board. The Revenge was commanded by Sir Richard Grenville, of Bideford, a man well known in the Spanish seas, and the terror of the Spanish sailors; so fierce he was said to be, that mythic stories passed from lip to lip about him, and, like Earl Talbot or Coeur de Lion, the nurses at the Azores frightened children with the sound of his name. “He was of great revenues,” they said, “of his own inheritance, but of unquiet mind, and greatly affected to wars,” and from his uncontrollable propensities for blood-eating, he had volunteered his services to the Queen; “of so hard a complexion was he, that I (John Huighen von Linschoten, who is our authority here, and who was with the Spanish fleet after the action) have been told by divers credible persons who stood and beheld him, that he would carouse three or four glasses of wine, and take the glasses between his teeth and crush them in pieces and swallow them down.” Such he was to the Spaniard. To the English he was a goodly and gallant gentleman, who had never turned his back upon an enemy, and was remarkable in that remarkable time for his constancy and daring. In this surprise at Florez he was in no haste to fly. He first saw all his sick on board and stowed away on the ballast, and then, with no more than 100 men left him to fight and work the ship, he deliberately weighed, uncertain, as it seemed at first, what he intended to do. The Spanish fleet were by this time on his weather bow, and he was persuaded (we here take his cousin Raleigh’s beautiful narrative and follow it in his words) “to cut his mainsail and cast about, and trust to the sailing of the ship.”

“But Sir Richard utterly refused to turn from the enemy, alledging that he would rather choose to die than to dishonour himself, his country, and her Majesty’s ship, persuading his company that he would pass through their two squadrons in spite of them, and enforce those of Seville to give him way, which he performed upon diverse of the foremost, who, as the mariners term it, sprang their luff, and fell under the lee of the Revenge. But the other course had been the better: and might right well have been answered in so great an impossibility of prevailing: notwithstanding, out of the greatness of his mind, he could not be persuaded.”

The wind was light; the San Philip, “a huge highcarged ship” of 1500 tons, came up to windward of him, and, taking the wind out of his sails, ran aboard him.

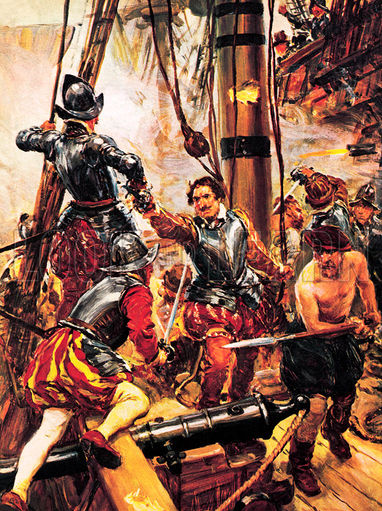

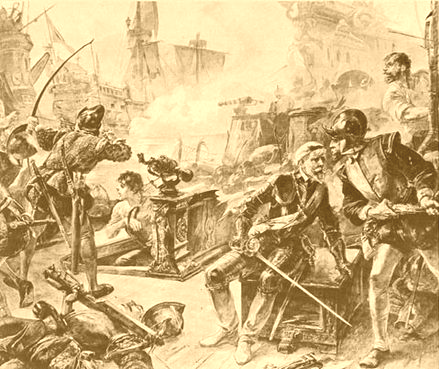

“After the Revenge was entangled with the San Philip, four others boarded her, two on her larboard and two on her starboard. The fight thus beginning at three o’clock in the afternoon continued very terrible all that evening. But the great San Philip, having received the lower tier of the Revenge, shifted herself with all diligence from her sides, utterly misliking her first entertainment. The Spanish ships were filled with soldiers, in some 200, besides the mariners, in some 500, in others 800. In ours there were none at all, besides the mariners, but the servants of the commander and some few voluntary gentlemen only. After many interchanged vollies of great ordnance and small shot, the Spaniards deliberated to enter the Revenge, and made divers attempts, hoping to force her by the multitude of their armed soldiers and musketeers; but were still repulsed again and again, and at all times beaten back into their own ship or into the sea. In the beginning of the fight the George Noble, of London, having received some shot through her by the Armadas, fell under the lee of the Revenge, and asked Sir Richard what he would command him; but being one of the victuallers, and of small force, Sir Richard bade him save himself and leave him to his fortune.”

A little touch of gallantry, which we should be glad to remember with the honour due to the brave English heart who commanded the George Noble; but his name has passed away, and his action is an in memoriam, on which time has effaced the writing. All that August night the fight continued, the stars rolling over in their sad majesty, but unseen through the sulphur clouds which hung over the scene. Ship after ship of the Spaniards came on upon the Revenge, “so that never less than two mighty galleons were at her side and aboard her,” washing up like waves upon a rock, and failing foiled and shattered back amidst the roar of the artillery. Before morning fifteen several armadas had assailed her, and all in vain; some had been sunk at her side; and the rest, “so ill approving of their entertainment, that at break of day they were far more willing to hearken to a composition, than hastily to make more assaults or entries.” “But as the day increased so our men decreased, and as the light grew more and more, by so much the more grew our discomfort, for none appeared in sight but enemies, save one small ship called the Pilgrim, commanded by Jacob Whiddon, who hovered all night to see the success, but in the morning bearing with the Revenge was hunted like a hare among many ravenous hounds– but escaped.”

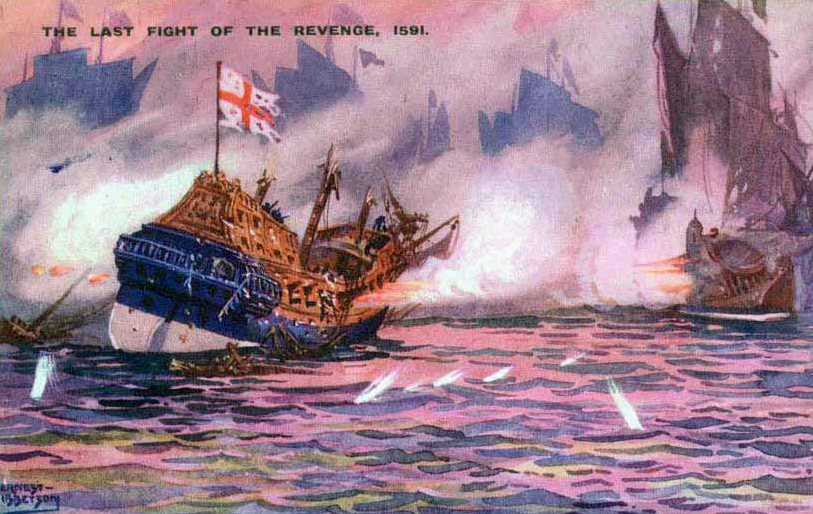

All the powder in the Revenge was now spent, all her pikes were broken, 40 out of her 100 men killed, and a great number of the rest wounded. Sir Richard, though badly hurt early in the battle, never forsook the deck till an hour before midnight; and was then shot through the body while his wounds were being dressed, and again in the head; and his surgeon was killed while attending on him. The masts were lying over the side, the rigging cut or broken, the upper works all shot in pieces, and the ship herself, unable to move, was settling slowly in the sea; the vast fleet of Spaniards lying round her in a ring like dogs round a dying lion, and wary of approaching him in his last agony. Sir Richard seeing that it was past hope, having fought for fifteen hours, and “having by estimation eight hundred shot of great artillery through him,” “commanded the master gunner, whom he knew to be a most resolute man, to split and sink the ship, that thereby nothing might remain of glory or victory to the Spaniards; seeing in so many hours they were not able to take her, having had above fifteen hours time, above ten thousand men, and fifty-three men-of-war to perform it withal; and persuaded the company, or as many as he could induce, to yield themselves unto God and to the mercy of none else; but as they had, like valiant resolute men, repulsed so many enemies, they should not now shorten the honour of their nation by prolonging their own lives for a few hours or a few days.”

The gunner and a few others consented. But such daimonie arete was more than could be expected of ordinary seamen. They had dared do all which did become men, and they were not more than men, at least than men were then. Two Spanish ships had gone down, above 1500 men were killed, and the Spanish Admiral could not induce any one of the rest of his fleet to board the Revenge again, “doubting lest Sir Richard would have blown up himself and them knowing his dangerous disposition.” Sir Richard lying disabled below, the captain finding the Spaniards as ready to entertain a composition as they could be to offer it, gained over the majority of the surviving crew; and the remainder then drawing back from the master gunner, they all, without further consulting their dying commander, surrendered on honourable terms. If unequal to the English in action, the Spaniards were at least as courteous in victory. It is due to them to say, that the conditions were faithfully observed. And “the ship being marvellous unsavourie,” Alonzo de Bacon, the Spanish Admiral, sent his boat to bring Sir Richard on board his own vessel.

Sir Richard, whose life was fast ebbing away, replied, that “he might do with his body what he list, for that he esteemed it not; and as he was carried out of the ship he swooned, and reviving again, desired the company to pray for him.”

The Admiral used him with all humanity, “commending his valour and worthiness, being unto them a rare spectacle and a resolution seldom approved.” The officers of the rest of the fleet, too, John Higgins tells us, crowded round to look at him, and a new fight had almost broken out between the Biscayans and the “Portugals,” each claiming the honour of having boarded the Revenge.

“In a few hours Sir Richard, feeling his end approaching, showed not any sign of faintness, but spake these words in Spanish, and said, ‘Here die I, Richard Grenville, with a joyful and quiet mind, for that I have ended my life as a true soldier ought to do that hath fought for his country, queen, religion, and honour. Whereby my soul most joyfully departeth out of this body, and shall always leave behind it an everlasting fame of a valiant and true soldier that hath done his duty as he was bound to do.’ When he had finished these or other such like words, he gave up the ghost with great and stout courage, and no man could perceive any sign of heaviness in him.”

Such was the fight at Florez, in that August of 1591, without its equal in such of the annals of mankind as the thing which we call history has preserved to us; scarcely equalled by the most glorious fate which the imagination of Barrere could invent for the Vengeur; nor did it end without a sequel awful as itself. Sea battles have been often followed by storms, and without a miracle; but with a miracle, as the Spaniards and the English alike believed, or without one, as we moderns would prefer believing, “there ensued on this action a tempest so terrible as was never seen or heard the like before.” A fleet of merchantmen joined the armada immediately after the battle, forming in all 140 sail; and of these 140, only 32 ever saw Spanish harbour. The rest all foundered, or were lost on the Azores. The men-of-war had been so shattered by shot as to be unable to carry sail, and the Revenge herself, disdaining to survive her commander, or as if to complete his own last baffled purpose, like Samson, buried herself and her 200 prize crew under the rocks of St. Michael’s.

“And it my well be thought and presumed,” says John Huyghen, “that it was no other than a just plague purposely sent upon the Spaniards; and that it might be truly said, the taking of the Revenge was justly revenged on them; and not by the might of force of man, but by the power of God. As some of them openly said in the Isle of Terceira, that they believed verily God would consume them, and that he took part with the Lutherans and heretics … saying further, that so soon as they had thrown the dead body of the Vice-Admiral Sir Richard Grenville overboard, they verily thought that as he had a devilish faith and religion, and therefore the devil loved him, so he presently sunk into the bottom of the sea and down into hell, where he raised up all the devils to the revenge of his death, and that they brought so great a storm and torments upon the Spaniards, because they only maintained the Catholic and Romish religion. Such and the like blasphemies against God they ceased not openly to utter.”

Impressive. I’m something of a student of military history, and I’ve never heard of that battle before.

Good to know that “outnumbered and outgunned” doesn’t equate to “defeated.”

He might have lost in localized sense, but that sort of action stiffens the spine of all who come after.