Editor’s Note: The following is extracted from Days to Remember: The British Empire in the Great War, by John Buchan and Henry Newbolt (published 1922).

On May 30, 1916, the Grand Fleet put to sea for one of its periodical sweeps. Admiral Jellicoe had information which gave him some hope that the enemy might at last be caught in the North Sea; and in fact, on the morning of the 31st, the German High Sea Fleet did come out, in ignorance of Jellicoe’s move, but in “hope of meeting with separate enemy divisions.” Admiral Scheer had with him the Battle Fleet of fifteen dreadnoughts and six older ships, with three divisions of cruisers, seven torpedo flotillas, and ten zeppelins; and in advance of these was a squadron of five battle-cruisers, under Admiral Hipper, with his own cruisers and destroyers. Advancing towards Hipper was the British Battle-Cruiser Fleet under Admiral Beatty—the Lion, Princess Royal, Tiger, Queen Mary, Indefatigable, and New Zealand—with the Fifth Battle Squadron under Rear-Admiral Evan-Thomas—the Barham, Valiant, Malaya, and Warspite; and in front of these were three light-cruiser squadrons under Commodore Goodenough, with four destroyer flotillas. Behind, and at a considerable distance, to avoid alarming the enemy too soon, came Admiral Jellicoe with the main fleet—twenty-four dreadnoughts in six divisions abreast of each other, and each in line ahead. He had with him also the Third Battle-Cruiser Squadron, three squadrons of cruisers, and three destroyer flotillas.

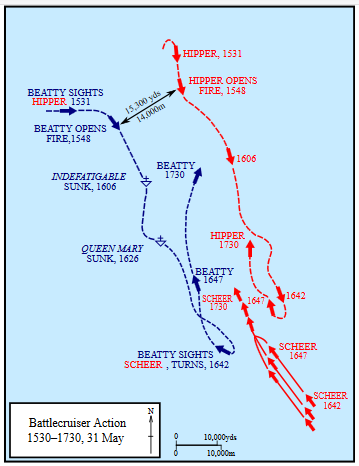

The light cruiser Galatea first sighted enemy ships at 2.20 p.m. Soon she reported the smoke of a fleet, and at 3.31 Beatty sighted Hipper and formed his line of battle. At 3.48 the action began at 18,500 yards, Hipper racing back towards his fleet and Beatty pursuing. The firing on both sides was rapid and accurate; in twelve minutes the leading ships on both sides had been seriously hit; six minutes more and a salvo, which reached her magazine, destroyed the Indefatigable.

The Fifth Battle Squadron now drew up and came into action. Immediately afterwards the enemy sent fifteen destroyers and a light cruiser to attack with torpedoes. They were met by our twelve destroyers, who fought with them a most gallant battle within the main battle, repulsing them and forcing their battle-cruisers to turn. The Nestor, the Nomad, and two enemy destroyers were sunk; the battle-cruisers swept on, and the action was resumed.

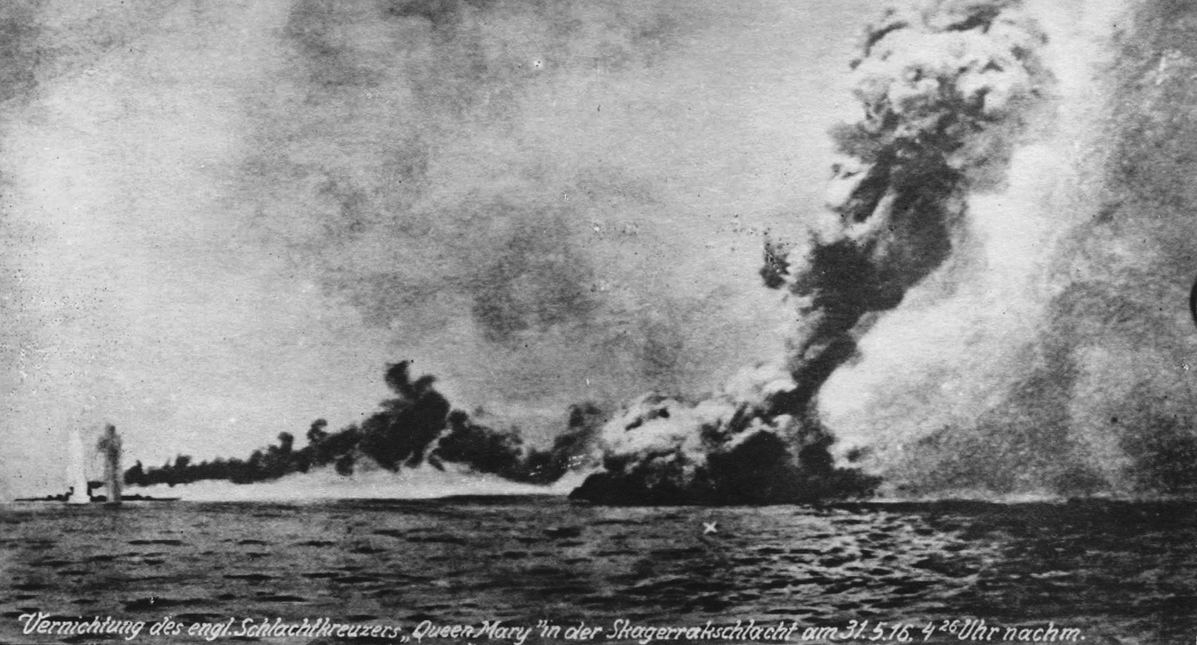

The enemy’s gunners now seemed to be losing their first accuracy, and at 4.18 the third ship of the German line was burning. But a few minutes later a salvo struck the Queen Mary in a vital part abreast of a turret; in one minute the ship was gone, and the Tiger, her next astern, passed over the place where she had been, without seeing any sign of her but smoke and falling debris. Admiral Beatty had lost two of his six battle-cruisers, and his flagship was damaged; but his tactics and his fighting spirit were in no way disturbed.

Twelve minutes later he was cheered by Commodore Goodenough reporting the German Battle Fleet. He had found the enemy at last in the open, and his business now was to draw them on towards the Grand Fleet. He recalled his destroyers and turned his whole force northward. Hipper, still steering south, fought him for a few minutes as they passed one another on opposite courses, and then turned north to follow him. The whole German fleet was now in line; but Beatty, having the superior speed, was able to overlap their head and keep their tail out of action. He engaged their five battle-cruisers with his own four, supported by the Barham and the New Zealand, while the Malaya and the Warspite were hammering their leading battleships.

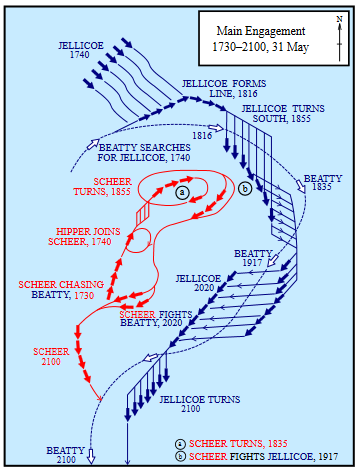

The Grand Fleet was now rapidly approaching, and Admiral Jellicoe had to prepare for the extremely difficult manoeuvre of joining battle with an enemy of whose position he was not fully informed. Gun-flashes were reported at 6.5 on the starboard bow, but the only ships visible were the Lion and other battle-cruisers steering east in thick mist. The admiral lost no time; at 6.8 he ordered two torpedo flotillas to his port front and one to starboard; then, after receiving a further report from Admiral Beatty, at 6.16 he ordered his six divisions of battleships to deploy eastwards, forming on the port wing column. He thus threatened to cut off the enemy from his base, and in order to close him the more quickly the deployment was made by divisions instead of in succession. The movement was entirely successful. At the same time the battle-cruisers were getting clear to the south and east, and Admiral Evan-Thomas’s four ships were forming astern of the fleet. They did this under fire, but without serious interference; the Warspite, whose helm jammed, was for a few moments carried over towards the enemy, but the German gunnery was no longer steady enough to hit her.

For the Germans the horizon was now filled with an unending line of British ships, and the sight, as their own officers said, “took the heart out of the men.” They were already “utterly crushed” by the masterly way in which Admiral Jellicoe had brought his huge fleet into action, and they saw that Admiral Beatty was outflanking them by “a model manoeuvre, a performance of the highest order.”[1] Their line bent away, first to the east, and then to the south, suffering heavily as it turned, and making not a hit in return.

They had, however, inflicted some losses on the British cruisers while the battleships were deploying. Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot, who had chased the light cruiser Wiesbaden (with the Defence, Warrior, and Black Prince) and crippled her between the lines, came under fire from two German battle-cruisers, and was blown up with the Defence, while the Warrior and the Black Prince were badly hit. Rear-Admiral Hood, too, met his fate; he had been scouting far to the south with the Invincible, Inflexible, and Indomitable, and was returning north to take station at the head of Beatty’s line. He executed this manoeuvre in grand style, and at once engaged the gigantic Derfflinger, hitting her repeatedly; but after two minutes of hard pounding a big shell blew up the Invincible’s magazine, and she sank with her admiral.

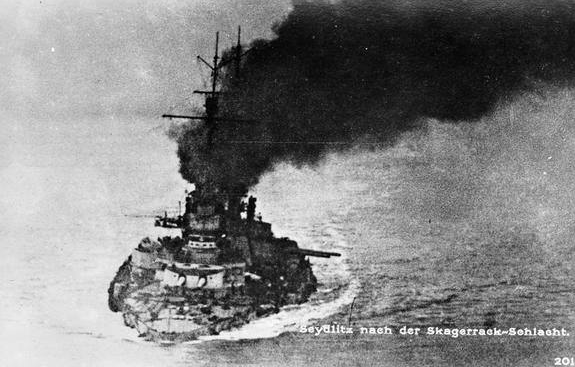

But by this time the action between the main fleets had been virtually lost and won. The German battleships at the head of Admiral Scheer’s line had suffered severely under the fire of the British rear divisions and were turning away south, while their battle-cruisers were in even worse plight. Two minutes after the Invincible sank, the Lutzow was no longer able to keep station, and Admiral Hipper was compelled to transfer his flag. But his difficulty was to find a sound ship; his next astern, the Derfflinger, had lost her wireless and was gaping with a hole 20 feet square in her bows; the Seydlitz had also lost her wireless, and had shipped several thousand tons of water. After being some time in a destroyer, the admiral went aboard the Moltke, and sent the Derfflinger to lead the line, with only the Von der Tann to follow.

Half dead though these three remaining ships were, their hardest task was yet before them. Admiral Scheer was in a desperate position, outmanoeuvred and outfought, with the Grand Fleet in the act of forming line between him and his base; and he is entitled to all credit for the plan which he adopted to secure his escape from total destruction. At 7.12 he ordered Hipper to attack Beatty in hope of breaking his encircling movement, and three minutes afterwards sent his destroyers to hold Jellicoe’s line with a torpedo attack, while he got away his crumpled battle fleet to the westward. These tactics cost him dear, but he was successful in increasing his distance and withdrawing his battleships from the fire which must speedily have overwhelmed them.

In the torpedo attack not less than twenty of his torpedoes were seen to cross the British line. All were avoided, for Admiral Jellicoe, acting on principles adopted by the Admiralty some time before, ordered his ships to turn away two or more points as soon as the attack was seen. When it was over they at once turned back towards the enemy, but Admiral Scheer had by that time disappeared westward into the mist. Of his twenty-one battleships twelve had been seriously damaged, and their united fire had made but a single hit on the twenty-six British battleships which engaged them—a hit which wounded three men in the Colossus.

The gallant Hipper suffered even more severely. He had no sooner started his attack on Beatty when the Derfflinger met more than her match in the Lion. In eight minutes she is reported by her chief gunnery officer, Captain von Hase, to have received twenty 15-inch shells, which destroyed turret after turret, carried away her fire control and chart-house, and set her on fire fore and aft. With only two heavy guns left, she drew off and went after her fleet, followed by the Von der Tann only. The Seydlitz and the Moltke had already left the line under cover of the smoke from the burning Lutzow. The light was now failing fast; the Lion was still hunting, but could no longer find her prey. In spite of some heavy hits, her admiral and his command were insatiable, and even disappointed. But they had, in fact, achieved a day’s fighting which is without a parallel—a battle-cruiser victory complete in itself.

Touch was now lost between the two fleets, and Admiral Jellicoe had to consider his dispositions for the night. He had completely succeeded in interposing between the enemy and their base, and his object was to bar their retreat and secure a final action next day. He therefore placed his battleships to the south in four columns a mile apart, his destroyers 5 miles to their rear, with the battle-cruisers and cruisers to the west, and two light-cruiser squadrons farther north and south. Finally, at 9.30, he sent the mine-laying flotilla leader, Abdiel, to lay a minefield towards the Horn Reef—a precaution which resulted in several explosions among enemy ships during the night.

The German commander-in-chief was well aware that in a daylight action he could expect nothing but destruction. He resolved on a rush for home in the dark, and here again he has the credit of a right decision and a right method. He sent his ships to make their way through in detachments. Some three or four light cruisers first ran into our destroyers, slightly damaged the Castor, received a torpedo hit, and vanished. Another group of cruisers attacked our Second Light Cruiser Squadron at very short range, inflicted heavy casualties on the Dublin and the Southampton, and disappeared, but with the loss of the light cruiser Frauenlob. The destroyer Sparrowhawk was sunk in action with a third group of cruisers, and a little later the Tipperary. At midnight some battleships passed near the same flotilla, and one, the Pommern, was torpedoed and sunk. Another battleship squadron followed soon after, and sank the destroyer Ardent.

At 1.46 a.m. the Twelfth Flotilla, farther north, sighted six Kaiser battleships and attacked them. Captain Stirling, in the Faulkner, torpedoed one, and some time later Commander Champion, in the Nomad, hit another; but the Germans claim that both the wounded ships reached port. The Ninth Flotilla lost the Turbulent, rammed by a large unknown vessel; but at 2.35 the destroyer Moresby, of the Thirteenth Flotilla, attacked four Deutschland battleships and torpedoed one. Lastly, it is believed that the Black Prince, who had been crippled hours before, was seen for a moment under the searchlights and guns of a number of enemy ships, who sank her at once. All this battle by night was fought under the most desperate conditions, the horror of darkness and the glare and crash of sudden death alternating for five hours; but it was far more ruinous to the German fleet than to the British.

When day broke, Admiral Jellicoe formed his fleet in line ahead and turned north; at 5.15 he called in the battle-cruisers; at 6 a.m. he sighted his cruisers, and at 9 the destroyers rejoined. He had now all his force in hand, except the Sixth Division of six battleships under Admiral Burney, whose flagship, the Marlborough, had been hit by a torpedo and was now being sent home under escort to be repaired. This, however, was no cause for delay, and Admiral Jellicoe patrolled the battle area till noon, in search of the enemy, moving first north, then south-west, and finally north by west.

It was clear that Admiral Scheer had no intention of further fighting. He had a zeppelin out scouting, and admits that she reported to him the position of the British fleet. But he was in no condition to move. He had inflicted on us a loss of three battle-cruisers, three armoured cruisers, and eight destroyers; while of his own ships one battleship, one battle-cruiser, four light cruisers, and five destroyers had been sunk. But his effective force had been diminished out of all proportion to ours; his battle-cruisers were in no condition to fight; he had discovered that the whole squadron of pre-dreadnoughts were unable to lie in a modern line of battle, while six of the remaining fifteen were unfit to be anywhere but in dock; of his eleven light cruisers ten had been hit, and four of them sunk. He had, in short, no fleet to make a fight with; whereas Admiral Jellicoe had available twenty-six powerful battleships, all but four of them untouched, six battle-cruisers out of nine, and all his light forces, except three cruisers sunk and three hard hit.

More fatal still, then and for ever, was the injury to the moral stamina and tradition of the German fleet. In that one day they passed from the militant to the mutinous state of mind, and their commander knew it. As Captain Persius wrote afterwards in the Berliner Tageblatt: “The losses sustained by our fleet were enormous, in spite of the fact that luck was on our side; and on June 1, 1916, it was clear to every one of intelligence that this fight would be, and must be, the only one to take place. Those in authority have often admitted this openly.” The Kaiser did his best to shout our victory down, and he was seconded, though more feebly, by German admirals who knew better. But the High Sea Fleet had failed completely to challenge the control of the sea, and henceforth degenerated towards the final surrender.

[1] Captain von Hase.