Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Khartoum Campaign, 1898, by Bennet Burleigh (published 1899). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 1)

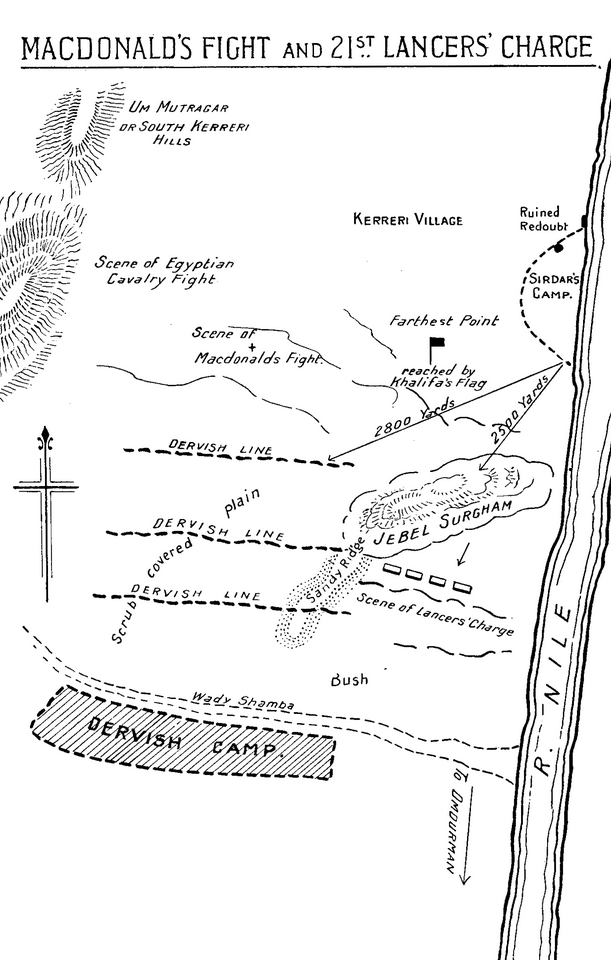

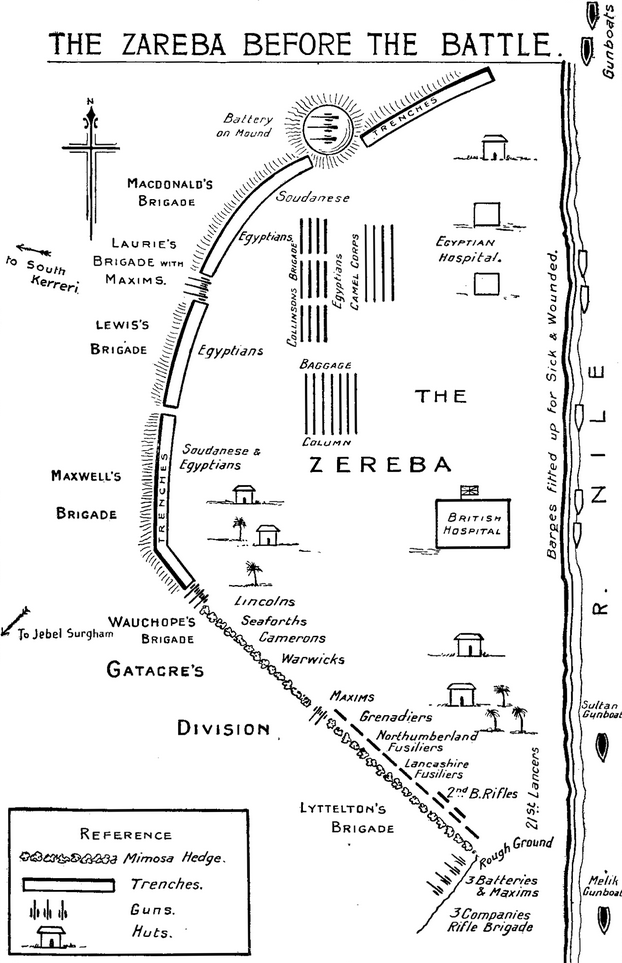

Before I deal with the second phase of the battle, there is something more to be said of the first. So far I have but written of the infantry and the artillery. It is no easy task to give a succinct account of a whole catalogue of events happening at the same time over so widespread a field. The battle of Omdurman was full of incident and of Homeric combats. Whilst we in the zereba were awaiting, ready and confident of the issue, the oncoming of the enemy, the two regiments of Egyptian cavalry and the Camel Corps, which had advanced on the right to Um Mutragan hills,—South Kerreri jebels,—like the 21st Lancers at El Surgham on the left were opposing the dervish advance. Their orders were to check the dervish left. The nine squadrons of troopers with Colonel Broadwood remained on the plain, but the Camel Corps, seven companies, with four Maxims, and the horse battery went up the west shoulder of one of the Um Mutragan hills. As the dervishes were advancing very rapidly, the four Maxims under Captain Franks were recalled into the zereba before they had fired a shot, or ere the mounted troops got into action. Three dismounted squadrons of Egyptian troopers thereupon went forward and temporarily occupied the position which had been assigned to the Maxims. The Camel Corps were already afoot, and had lined the crest and slopes of the hill, waiting to fire as soon as the Mahdists came within range. When the big columns of the dervishes, led by the Sheikh Ed Din, Khalifa Khalil and Ali Wad Helu, approached nearer, Major Young’s horse battery of six guns began shelling them at 1500 yards range. The Camel Corps then opened a sharp fusilade, and within a few minutes a brisk fight was going on. But the enemy neither halted nor stayed in face of the fire. It only served to quicken their pace, and they ran forward shooting rapidly the while. An order was sent to the Camel Corps to retire at once, as the dervishes were seen to be trying to cut them off by advancing on both sides of the hill. Before the order carried by Lieutenant Lord Tullibardine actually reached them, they had suffered severely and were falling back. A large number of men and camels had been hit. The cavalry endeavoured to relieve the pressure. Ultimately, though hotly pressed by the dervishes who got to within a few hundred yards, the Horse Artillery and the Camel Corps took up a second position upon a ridge fully half a mile to the rear. From the zereba we could see that the mounted troops were being hurried, and that the action taking place was an exceedingly sharp one. In fact, before the guns and the Camel Corps got into position upon the second ridge, the dervishes were firing at them from the summit and slopes of Um Mutragan. Major Young had only fired a round or two from his guns when the enemy were but 600 yards off. The dervishes were swarming along the eastern sides of Um Mutragan, running direct for the guns and the Camel Corps. Colonel Broadwood formed his cavalry up to charge, and Major Mahan led his regiment of “Gippy” troopers forward. But a detachment of the Camel Corps under Captain Hopkinson pluckily stood their ground, covering the retirement of their comrades and the batteries down the very rough slope. Unfortunately, Captain Hopkinson was severely wounded, and a native officer and a number of men were killed. Falling back along the east and north sides of the hill the force was sorely pressed by the enemy, and a series of brave and bristling hand-to-hand encounters took place. Near the crest of a hill, one of the “wheelers” of the horse battery was shot. The traces could not be cut in time, so the gun had to be abandoned. At the critical moment another gun collided with it, and was upset beside the first, so both pieces, with, later on, a third, fell temporarily into the dervishes’ hands. They did nothing with them. Colonel Broadwood, on finding the enemy pushing so determinedly, as though they had struck the whole of the Sirdar’s army, directed the Camel Corps to retire to the zereba. Luckily, two of the gunboats, getting sight and range of the eager dervishes who were hunting the camelmen, began firing with every piece of armament they could bring to bear. I assume they saved the situation, for the Camel Corps were hard pressed, and lost eighty men before they got to the river and into a safe position under the shelter of the gunboats and Macdonald’s brigade, which was at the north end of the zereba. The myth of a Camel Corps as a useful fighting unit had been exploded. Meantime, Colonel Broadwood’s troopers rode away to the north, trying to shake off outflanking parties of dervishes. The Sheikh Ed Din and Khalil continued to pursue the cavalry with great eagerness and venom. Several times bodies of 200 and 300 Baggara horsemen threatened to charge, but Majors Mahan and Le Gallias turning upon these riders sent them flying back helter-skelter. For five miles the cavalry was, so to speak, driven from pillar to post by the dervish infantry. When the pursuit had been pressed four miles, and more, north of the zereba, Major Mahan succeeded in clearing the flanks, whereupon the dervishes gave up the chase and sat down to rest. One advantage came of the hot-headed pursuit; it led two columns of the enemy away, and only a portion of those dervish commands got back in time to engage in the assault upon the zereba.

When the Khalifa Abdullah, who escaped being killed, retired with his shattered army after their futile attack behind the western hills a little south of Um Mutragan, it was thought that the fighting spirit had been knocked out of the enemy. There was no assurance that if the Sirdar and his men followed after the Khalifa the dervishes would risk a second battle. They had the legs of us, and would presumably use them to run away, or to harass us if we went after them into the wilderness. Discreetly and shrewdly the Sirdar decided to march his army straight into Omdurman, but six miles distant. We were able to move upon inside lines and over open ground, so that if the Khalifa meant to race us for the place he would have to fight at a disadvantage. The command was issued about 8.30 to prepare to march out of camp for Omdurman. Our wounded, who had been borne from the field on stretchers, were put upon the floating hospitals. Colonel Collinson’s brigade was told off to guard stores and material to be left behind for a time. Ammunition was drawn from the reserve stores afloat, and the supply columns’ boxes were refilled, as well as the battery limbers and the men’s pouches. The army was again equipped for action as though it had not fired a shot. Camels were reloaded, and all was in readiness for a start. We could see bodies of the enemy still flaunting their banners, and watching our every movement from the western hills. Wounded dervishes were crawling and dragging wearily back from their fated field towards Omdurman. There was the occasional crack of a rifle as some dervish sniped us, or invited a shot from the Egyptian battalions. Many of our black soldiers actually wept with vexation on being withdrawn from the firing line to make room for guns and Maxims. One man, who declared he had not fired a shot, was only comforted on being assured that the battle was not altogether over, that his chance would come later.

I think it was about 9 a.m. when the Sirdar’s army, re-formed for marching, stepped clear of the zereba and the trenches. The order of advance for the infantry was as before, in échelon of brigades, the British being on the left and in front. Lyttelton’s 2nd brigade was leading, Wauchope’s was behind it. On the right were Maxwell’s and Lewis’s brigades. Macdonald was to look after our extreme right rear flank, whilst Collinson followed in the gap nearer the river. Lyttelton’s brigade was directed to pass to the left, east of Jebel Surgham, Maxwell’s left was to extend to and pass over the hill, whilst Lewis and Macdonald would sweep part of the valley between Surgham and South Kerreri. Such was the general direction to be taken, exposing a front measured on the bias, of fully one mile. Once more the 21st Lancers trotted out towards Jebel Surgham to make sure there were no large bodies of the enemy in hiding. Keeping somewhat closer to the river than previously, and avoiding the main field of battle, they passed to the east of the hill. Part of their duty was to check, if possible, any attempt of the enemy to fall back into Omdurman, or at least delay such an operation. Great numbers of scattered dervishes were seen, some of whom fired at the troopers. Keeping on until about half a mile or more south of Surgham, a small party of dervish cavalry, about thirty, and what was thought to be a few footmen, were seen hiding in a depression or khor. Colonel Martin determined to push the party back and interpose his regiment between them and Omdurman. A few spattering shots came from the khor, as the four squadrons formed in line to charge. “A” squadron, under Major Finn, was on the right, next it was “B” squadron, commanded by Major Fowle. On the left of “B” was “D,” or the made-up squadron, led by Captain Eadon, and “C” squadron, under Captain Doyne, was on the extreme left.

Leading the regiment forward at a gallop from a point 300 yards away, the Lancers dashed at the enemy, who at once opened a sharp musketry fire upon our troopers. A few casualties occurred before the dervishes were reached, but the squadrons closed in and setting the spurs into their horses rushed headlong for the enemy. In an instant it was seen that, instead of 200 men, the 21st had been called upon to charge nearly 1500 fierce Mahdists lying concealed in a narrow, but in places deep and rugged, khor. In corners the enemy were packed nearly fifteen deep. Down a three-foot drop went the Lancers. There was a moment or so of wild work, thrusting of steel, lance, and sword, and rapid revolver shooting. Somehow the regiment struggled through, and up the bank on the south side. Nigh a score of lances had been left in dervish bodies, some broken, others intact. Lieutenant Wormwald made a point at a fleeing Baggara, but his sabre bent and had to be laid aside. Captain Fair’s sword snapped over dervish steel, and he flung the hilt in his opponent’s face. Major Finn used his revolver, missing but two out of six shots. Colonel Martin rode clean through without a weapon in his hand. Then the regiment rallied 200 yards beyond the slope. Probably 80 dervishes had been cut or knocked down by the shock. But the few seconds’ bloody work had been almost equally disastrous for the Lancers. Lieutenant R. Grenfell and fifteen men had been left dead in the khor. It so happened that the squadrons on the two wings had comparatively easy going and did not strike the densest groups of the enemy. Squadrons “D” and “B” fared badly, and particularly Lieutenant Grenfell’s troop, of whom ten men fell with that officer. In their front was a high rough bank of boulders, almost impassable for a horse. They were cut down and hacked by the enemy. His brother, Lieutenant H. M. Grenfell, subsequently recovered his watch, which had been thrust through by a dervish lance point and had stopped at 8.40 a.m. Young Robert Grenfell was probably struck from behind with a Mahdist sword blade, and killed instantly as his charger was endeavouring to scramble up the wall of loose stones and rock. Melées were taking place to right and left, every trooper having any difficulty in getting out of the khor being instantly surrounded by mounted dervishes and footmen. Lieutenant Nesham in leading his troop was savagely attacked. His helmet was cut off his head, and he was wounded severely upon the left forearm and right leg. The bridle reins of his charger were cut, but he piloted the animal safely through. “B” and “D” squadrons lost respectively nine killed and eleven wounded, and seven killed and eight wounded. Lieutenant Molyneux, R.H.G., had his horse knocked over. He called to a trooper not to leave him, and the man replied, “All right, sir, I won’t leave you.” Together they had a busy time. Two dervishes attacked the lieutenant; he shot one, but the other cut him over the right arm, causing him to drop his revolver. He then ran for it and got away. Lieutenants Brinton and Pirie received wounds. Private Ives of “A” squadron picked up a wounded comrade in the nullah, and got chased and separated from his regiment. He reached the infantry covered with his comrade’s blood. The latter was killed, but Ives was not seriously hurt.

Lieutenant Montmorency, having got through safely, turned back to look for his troop-sergeant Carter. Captain Kenna went with him. At the moment they were not aware that young Grenfell had fallen. Lieutenants T. Connally and Winston Churchill also turned about to rescue two non-commissioned officers of their respective troops. They succeeded in their laudable task. Surgeon-Captain Pinches, whose horse had been shot under him on the north side of the khor, was saved by the pluck of his orderly, Private Peddar, who brought him out on his horse. Meanwhile, Captain Kenna and Lieutenant Montmorency, who were accompanied by Corporal Swarbrick, saw Lieutenant Grenfell’s body and tried to recover it. They fired at the dervishes with their revolvers, and drove them back. Dismounting, Montmorency and Kenna tried to lift the body upon the lieutenant’s horse. Unluckily, the animal took fright and bolted. Swarbrick went after it. Major Wyndham, the second in command of the Lancers, had his horse shot in the khor. He was one of the few who escaped after such a calamity. The animal fortunately carried him across, up, and beyond the slope ere it dropped down dead. Lieutenant Smith, who was near, offered him a seat, and the Major grasped the stirrup to mount. Just then—for these events have taken longer in telling than in happening—Montmorency and Kenna found the dervishes pressing them hard, both being in instant danger of being killed. Swarbrick had brought back the horse, and Kenna turned to Major Wyndham and gave him a seat behind, then leaving Grenfell’s body they rejoined their command. Proceeding about 300 yards to the south-east from the scene of the charge, Colonel Martin dismounted his whole regiment, and opened fire upon the dervishes. Getting into position where his men could fire down the khor, a detachment of troopers soon drove away the last of the enemy. Thereupon a party advanced and recovered the bodies of Lieutenant Grenfell and the others who had fallen in the khor.

It was a daring, a great feat of arms for a weakened regiment of 320 men to charge in line through a compact body of 1500 dervish footmen, packed in a natural earthwork. Perhaps it is even a more remarkable feat that they were able to cut their way through with only a loss of 22 killed and 50 officers and men wounded and 119 casualties in horseflesh. Many of the poor beasts only lived long enough to carry their riders out of the jaws of death. One cannot refuse to admire the gallant deed, which probably had as good an effect upon the enemy as a bigger victory of our arms; but the obvious comment will be that made about the Balaclava charge—equally heroic, and not, I honestly think, less useful—”C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre.” On searching the ground inside the khor sixty dead dervishes were found where the central squadrons passed over. A small heap lay around Lieutenant Grenfell and his troop. Four of our men were found alive, but died before they could be moved. A sword-cut had cleft young Grenfell’s head and given him a painless death. The bodies were, as usual, full of sword-cuts and spear-thrusts inflicted by the enemy before and after the victims had breathed their last.

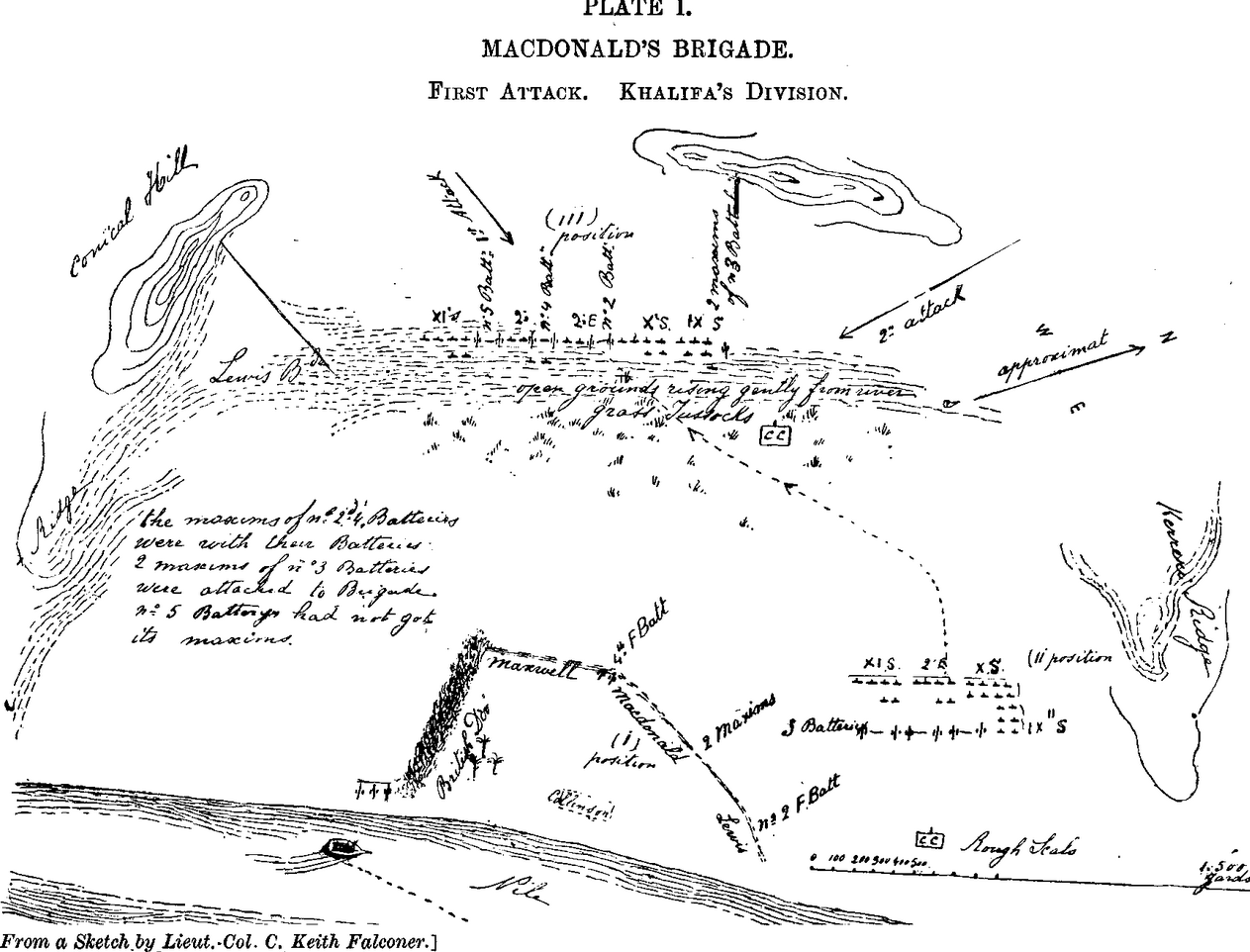

It is a long tale I am telling, but yet the most brilliant and heroic episode of a day so full of glowing incident remains to be told. About 9.20 a.m. the Sirdar led his troops slowly forward towards Omdurman. Great as the slaughter had been, thousands of dervishes could be seen still watching us from the western hills. Behind them they had re-formed again into compact divisions. The Sirdar’s direction, I have said, was that his troops were to swing clear of the zereba and march in échelon with the 2nd British brigade leading Moving out a few hundred yards, Lyttelton’s brigade, which, as before, marched in four parallel columns of battalions, the Guards on the right, swung to the left. They were making to pass Surgham, leaving it upon their right. The 1st British brigade, Major-General Wauchope’s, was behind, and had turned to the left to follow the 2nd brigade. Behind, in succession, were Maxwell’s, Lewis’s, and Macdonald’s Egyptian or Khedivial brigades. The nature of the ground forced some of them out of their true relative positions. Macdonald had marched out due west. The dervishes, like wolves upon the scent for prey, suddenly sprang from unexpected lairs. With swifter feet and fiercer courage than ever they dashed for the comparatively isolated brigade of Colonel Macdonald. Although I was far away at the moment with the 1st or Lyttelton’s brigade, the shouts, the noise of the descending tornado reached me there. From behind the southern slope of Um Mutragan hills the Khalifa was charging Macdonald with an intact column of 12,000 men, the banner-bearers and mounted Emirs again in the forefront. A broad stream, running from the south and the east, of dervishes who had lain hidden sprang up and ran to strike in upon the south-east corner of Macdonald’s brigade. Worse still, Sheikhs Ed Din and Khalifa Khalil, returned from chasing the Egyptian cavalry, were hastening with their division at full speed to attack him in rear. Scarcely a soul in the Sirdar’s army, from the leader down, but saw the unexpected singular peril of the situation. I turned to a friend and said, “Macdonald is in for a terrible time. Will any get out of it?” Then I rode at a gallop, disregarding the venomous dervishes hanging about, up the slopes of Surgham, where, spread like a picture, the scene lay before me. Prompt in execution, the Sirdar rapidly issued orders for the artillery and Maxims to open fire upon the Khalifa’s big column. Eagerly he watched the batteries coming into action. At the same moment the remaining brigades were wheeled to face west, and Major-General Wauchope’s was sent back at the double to help the staunch battalions of Colonel Macdonald, now beset on all sides. Fortunately Macdonald knew his men thoroughly, for he had had the training of all of them, the 9th, 10th, 11th Soudanese, and the 2nd Egyptians under Major Pink. No force could have been in time to save them had they not fought and saved themselves. Lewis’s brigade was nearest, but it was almost a mile away, and the dervishes were wont to move so that ordinary troops seemed to stand still. And Lewis, for reasons of his own, determined to remain where he was.

Indecision or flurry would have totally wrecked Macdonald’s brigade, but happily their brigadier well knew his business. An order was sent him which, had it been obeyed, would have ensured inevitable disaster to the brigade, if not a catastrophe to the army. He was bade to retire by, possibly, his division commander. Macdonald knew better than attempt a retrograde movement in the face of so fleet and daring a foe. It would have spelled annihilation. The sturdy Highlandman said, “I’ll no do it. I’ll see them d——d first. We maun just fight.” And meanwhile Major-General A. Hunter was scurrying to hurry up reinforcements—a wise measure. Other messages which could not reach Macdonald in time were being sent to him by the Sirdar to try and hold on, that help was coming. Yes; but the surging dervish columns were converging upon the brigade upon three sides. Surely it would be engulfed and swept away was the fear in most minds. And what other wreck would follow? Ah! that could wait for answer. It was a crucial moment. A single Khedivial brigade was going to be tested in a way from which only British squares had emerged victorious. Most fortunately, Colonel Long, R.A., had sent three batteries to accompany Colonel Macdonald’s brigade, namely, Peake’s, Lawrie’s, and de Rougemont’s. The guns were the handy and deadly Maxim-Nordenfeldt (12½-pounders). Macdonald had marched out with the 11th Soudanese on his left, the 2nd Egyptian, under Major Pink, in the centre, and the 10th Soudanese on the right, all being in line. Behind the 10th, in column, were the 9th Soudanese. Major Walter commanded the 9th, Major Nason the 10th, and Major Jackson the 11th Soudanese battalions. Going forward to meet the Khalifa’s force Colonel Macdonald threw his whole brigade practically into line, disregarding for the moment the assaulting columns of Sheikh Ed Din, which providentially were a little behind in the attack. The batteries went to the front in openings between the battalions and smote the faces of the dervish columns. Steadily the infantry fired, the blacks in their own pet fashion independently, the 2nd Egyptians in careful, well-aimed volleys. Afar we could see and rejoice that the brigade was giving a magnificent account of itself. The Khalifa’s dervishes were being hurled broadcast to the ground. Major Williams at last with his 15-pounders, our other batteries, and the Maxims were finding the range and ripping into shreds the solid lines of dervishes. Still the enemy pressed on, their footmen reaching to within 200 yards of Macdonald’s line. Scores of Emirs and lesser leaders, with spearmen and swordsmen, fell only a few feet from the guns and the unshaken Khedivial infantry. It is said one or two threw spears across the indomitable soldiery, and other dervishes turned the flanks, but were instantly despatched. A few salvoes and volleys shook the looser attacking columns of dervishes. The Khalifa’s division had at length received such a surfeit of withering fire that the rear lines began to hold back, and the desperate rushes of the chiefs and their personal retainers grew fewer and feebler. But Sheikh Ed Din was at length within 1000 yards running with his confident legions to encompass and destroy the 1st Khedivial brigade. Macdonald, as soon as he saw that he could hold his own against the whole array of the Khalifa’s personally commanded divisions, threw back his right, the 9th, and one and then another battery. He was now fairly beset on all sides, but fighting splendidly, doggedly. The dervishes, taking fresh courage, made redoubled efforts to destroy him. It was by far the finest, the most heroic struggle of the day. A second battalion, the famous fighting 11th Soudanese, under Jackson, which lost so heavily at Atbara, swung round and interposed itself to Khalil’s and Sheikh Ed Din’s fierce followers. Furious as was the blast of lead and iron, the dervishes had all but forged in between the 9th and 11th battalions, when the 2nd Egyptian, wheeling at the double, filled the gap. Without hesitation the fellaheen, let it be said, stood their ground, and, full of confidence, called to encourage each other, and gave shot and bayonet point to the few more truculent dervishes who, escaping shot and shell, dashed against their line.

It was a tough, protracted struggle, but Colonel Macdonald was slowly, determinedly, freeing himself and winning all along the line. The Camel Corps came out to his assistance, and formed up some distance off on the right of the 11th Soudanese. Shells and showers of bullets from the Maxims on the gunboats drove back the rear lines of Sheikh Ed Din’s men. Three battalions of Wauchope’s got up to assist in completing the rout of the Khalifa. The Lincolns, doubling to the right, got in line on the left of the Camel Corps, and assisted in finishing off the retreating bands of the Khalifa’s son. I then saw the dervishes for the first time in all those years of campaigns turn tail, stoop, and fairly run for their lives to the shelter of the hills. It was a devil-take-the-hindmost race, and the only one I ever saw them engage in through half a score of battles. Beyond all else the double honours of the day had been won by Colonel Macdonald and his Khedivial brigade, and that without any help that need be weighed against the glory of his single-handed triumph. He achieved the victory entirely off his own bat, so to speak, proving himself a tactician and a soldier as well as what he has long been known to be, the bravest of the brave. I but repeat the expressions in everybody’s mouth who saw the wonderful way in which he snatched success from what looked like certain disaster. The army has a hero and a thorough soldier in Macdonald, and if the public want either they need seek no farther. I know that the Sirdar and his staff fully recognised the nature of the service he rendered. A non-combatant general officer who witnessed the scene declared one might see 500 battles and never such another able handling of men in presence of an enemy. When the final rout of the dervishes had been achieved it was about 10 a.m. The Sirdar wheeled his brigades to the left, into their original position, and marched them straightway towards Omdurman. Passing slowly over the battle-field the awful extent of the carnage was made evident. In my first wires I insisted that our total casualties were about 500, and the enemy’s over 10,000 slain. Macdonald lost about 128 men. I subsequently ascertained that the total of our killed and wounded was about 524. The dervish killed certainly numbered over 15,000, and their wounded probably as many more. Mahdism had been more than “smashed,” it had been all but extirpated. So may all plagues end.

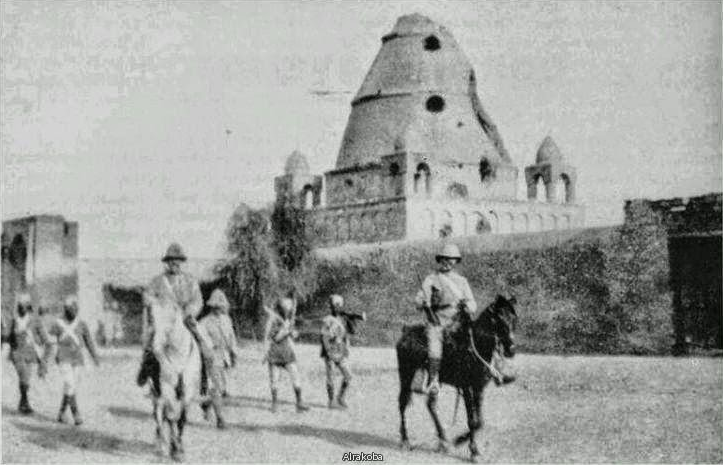

On the march the British troops having to swing aside from where the Khalifa’s black flag still stood, it fell into the hands of an Egyptian brigade, and was conveyed to the Sirdar by Captain Sir Henry Rawlinson and Major Lord Edward Cecil. It was given to an Egyptian orderly to carry behind the headquarters staff. Unfortunately, it attracted the attention of some of our own people on the gunboats who were unaware it had been captured. Several rounds were fired at the supposed dervishes following it, and then it was discreetly furled for a time. By midday the army had arrived at the northern outskirts of Omdurman, where the troops were halted near the Nile to obtain food and water. I rode forward and saw that there were thousands of dervishes in the town, many of them Baggara. The cavalry were sent as speedily as possible, after watering and feeding the horses, towards the south side of the town, and the gunboats were ordered up the river. Several deputations of citizens, Greeks and natives, came out and saw Slatin Pasha and the Sirdar. It was stated that the people would surrender, and that there would be no difficulty in occupying the place. The Khalifa, it was said, was in his house and must yield. Slatin Pasha, by the way, had gone over the battle-field and identified many of the slain Emirs. At 4.20 p.m., with two batteries, several Maxims and Colonel Maxwell’s brigade leading, the Sirdar rode down the great north thoroughfare towards the central part of the squalid town. The houses, or more accurately huts, were full of dervishes, hundreds of whom were severely wounded. Women and children flocked into the streets, raising cries of welcome to us. Of all the vile, dirty places on earth, Omdurman must rank first. There was no effort at sanitary observances, and dead animals, camels, horses, donkeys, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, in all stages of putrefaction, lay about the streets and lanes. There were dead men, women, and children, too, lying in the open.

We passed the big rectangular stone wall enclosing the Khalifa’s special quarters. Within its area were his Mulazimin or body-guards’ quarters, his granaries, treasuries, arsenal, the Mahdi’s tomb, and the great praying square, misnamed the Mosque. Except the tomb, the Khalifa’s and his sons’ houses, the town was void of buildings of any style or finish. I admit the great stone wall was of good masonry, and so was the well-finished praying-square wall. The Sirdar and party were frequently shot at, particularly on nearing the Khalifa’s quarters. Abdullah slipped out with his treasures as the Sirdar arrived at his gate. It was long after sunset and dark when, with difficulty, the prison was reached, and Charles Neufeld brought out of his loathsome den, where he had spent eleven years in chains. He looked well, notwithstanding his long and irksome captivity, feeling, as he said, like a man drunk with new wine, on account of his release. That night I helped to relieve him from his fetters, freeing the limbs from the heavy bar and chains. Tired, worn out, without water or food, the Sirdar and his staff, as well as many more of us, were glad to escape out of Omdurman back to where the British camp was pitched in the northern outskirts. There I and others lay down and fell asleep on the bare desert, hoping to wake and find that our servants and baggage had turned up. Two of my colleagues had fared worse than I that day. Colonel F. Rhodes, of the Times, had been shot in the shoulder within the zereba early in the fight, and the Hon. Hubert Howard, of the New York Herald, was killed almost under my eyes, in the paved courtyard of the Khalifa, opposite the Mahdi’s tomb. Such is the hasty record of as exciting and interesting a battle and a day’s campaigning as it ever fell to mortal man to witness. Neither in my experience nor in my reading can I recall so strange and picturesque a series of incidents happening within the brief period of twelve hours.