Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Ten Great Events in History, by James Johonnot (published 1887).

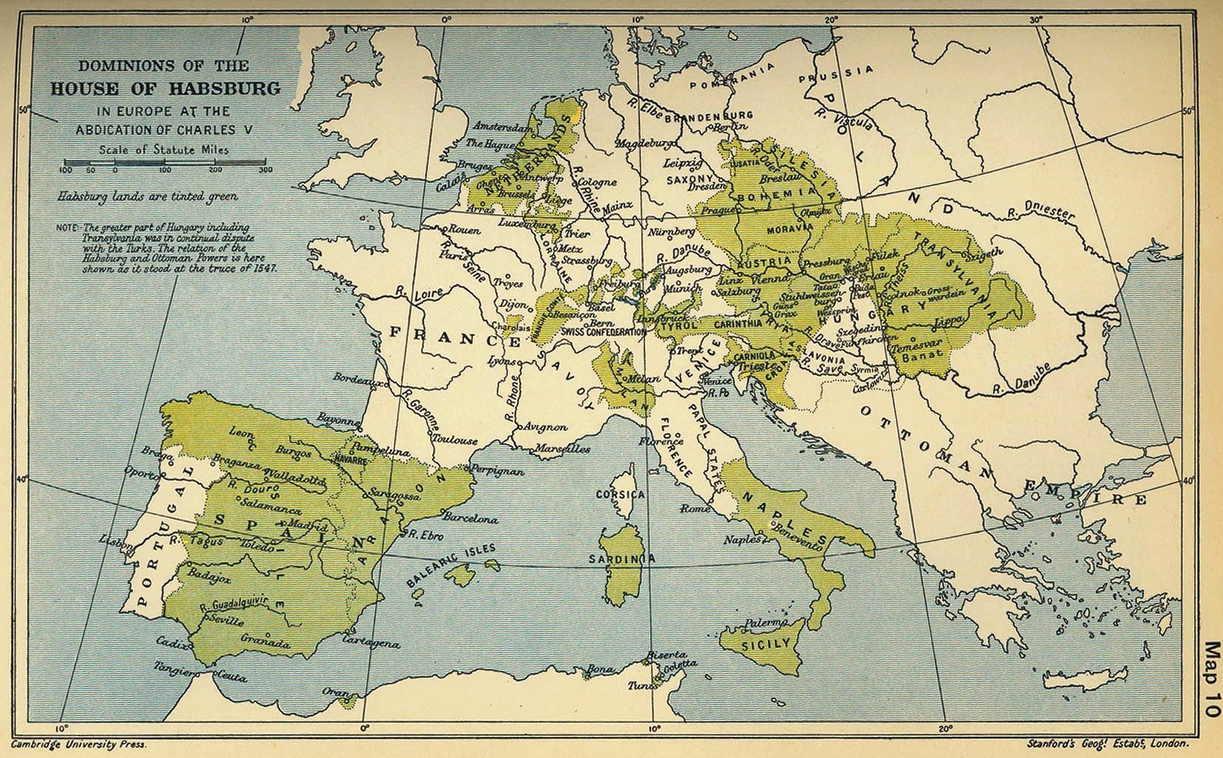

On the abdication of Charles V, in 1555, Spain and the low countries fell to the lot of Philip II. Notwithstanding the riches which had poured into Spain from the plunder of Mexico and Peru, the Netherlands were the richest part of Philip’s dominions, yielding him a princely revenue. But the free spirit manifested by these artisans, in their homes by the sea, was contrary to all Philip’s ideas of government, and was constantly galling to his personal pride. So he determined to reduce his Teutonic subjects to the same degree of abject submission that he had the residents of the sunny lands of Spain. To give intensity to his resolve, Philip was a cold-blooded bigot, and in carrying out his state designs he was also gratifying his religious animosities, and giving expression to his almost insane religious hatreds. His policy was directly calculated to ruin the most prosperous part of his own dominions—to “kill the goose which laid the golden egg.”

Philip spent the first five years of his reign in the Netherlands, waiting the issue of a war in which he was engaged with France. During this period his Flemish and Dutch subjects began to have some experience of his government. They observed with alarm that the king hated the country and distrusted the people. He would speak no other language than Spanish; his counselors were Spaniards; he kept Spaniards alone about his person, and it was to Spaniards that all vacant posts were assigned. Besides, certain of his measures gave great dissatisfaction. He re-enacted the persecuting edicts against the Protestants which his father, in the end of his reign, had suffered to fall into disuse; and the severities which ensued began to drive hundreds of the most useful citizens out of the country, as well as to injure trade by deterring Protestant merchants from the Dutch and Flemish ports. Dark hints, too, were thrown out that he intended to establish an ecclesiastical court in the Netherlands similar to the Spanish Inquisition, and the spirit of Catholics as well as Protestants revolted from the thought that this chamber of horrors should ever become one of the institutions of their free land.

He had also increased the number of bishops in the Netherlands from five to seventeen; and this was regarded as the mere appointment of twelve persons devoted to the Spanish interest, who would help, if necessary, to overawe the people. Lastly, he kept the provinces full of Spanish troops, and this was in direct violation of a fundamental law of the country.

Against these measures the nobles and citizens complained bitterly, and from them drew sad anticipations of the future. Nor were they more satisfied with the address in which, through the bishop of Arras as his spokesman, he took farewell of them at a convention of the states held at Ghent previous to his departure to Spain. The oration recommended severity against heresy, and only promised the withdrawal of the foreign troops. The reply of the states was firm and bold, and the recollection of it must have rankled afterward in the revengeful mind of Philip. “I would rather be no king at all,” he said to one of his ministers at the time, “than have heretics for my subjects.” But suppressing his resentment in the mean time, he set sail for Spain in August, 1559, leaving his half-sister to act as his viceroy in the Netherlands.

At this juncture, while the Dutch were threatened by a complete subjugation of their liberties, a champion arose who in the end proved more than a match for Philip both in diplomatic fields and in military operations. This was William, Prince of Orange, one of the highest nobility, but with his whole heart in sympathy with the people. Inheriting a personality almost perfect in physical, mental, and moral vigor and harmony, he early manifested a prudence and wisdom which gained for him the entire confidence of the suspicious and experienced Charles V.

It was on the arm of William of Orange that Charles had leaned for support on that memorable day when, in the assembly of the states at Brussels, he rose feebly from his seat, and declared his abdication of the sovereign power; and it was said that one of Charles’s last advices to his son Philip was to cultivate the goodwill of the people of the Netherlands, and especially to defer to the counsels of the Prince of Orange. When, therefore, in the year 1555, Philip began his rule in the Netherlands, there were few persons who were either better entitled or more truly disposed to act the part of faithful and loyal advisers than William of Nassau, then twenty-two years of age.

But, close as had been William’s relations to the late emperor, there were stronger principles and feelings in his mind than gratitude to the son of the monarch whom he had loved. He had thought deeply on the question, how a nation should be governed, and had come to entertain opinions very hostile to arbitrary power; he had observed what appeared to him, as a Catholic, gross blunders in the mode of treating religious differences; he had imbibed deeply the Dutch spirit of independence; and it was the most earnest wish of his heart to see the Netherlands prosperous and happy. Nor was he at all a visionary, or a man whose activity would be officious and troublesome; he was eminently a practical man, one who had a strong sense of what is expedient in existing circumstances; and his manner was so grave and quiet that he obtained the name of “William the Silent.” Still, many things occurred during Philip’s four years’ residence in the Netherlands to make him speak out and remonstrate. He was one of those who tried to get the king to use gentler and more popular measures, and the consequence was that a decided aversion grew up in the dark and haughty mind of Philip to the Prince of Orange.

After the departure of Philip the administration of the Duchess of Parma produced violent discontent. The persecutions of the Protestants were becoming so fierce that, over and above the suffering inflicted on individuals, the commerce of the country was sensibly falling off. The establishment of a court like the Inquisition was still in contemplation; Spaniards were still appointed to places of trust in preference to Flemings; and finally, the Spanish soldiers, who ought to have been removed long ago, were still burdening the country with their presence. The woes of the people were becoming intolerable; occasionally there were slight outbreaks of violence; and a low murmur of vehement feeling ran through the whole population, foreboding a general eruption. “Our poor fatherland!” they said to each other; “God has afflicted as with two enemies, water and Spaniards; we have built dikes and overcome the one, but how shall we get rid of the other? Why, if nothing better occurs, we know one way at least, and we shall keep it in reserve—we can set the two enemies against each other. We can break down the dikes, inundate the country, and let the water and the Spaniards fight it out between them.”

About this time, too, the decrees of the famous Council of Trent, which had been convened in 1545 to take into consideration the state of the Church and the means of checking the new religion, and which had closed its sittings in the end of 1563, were made public; and Philip, the most zealous Catholic of his time, issued immediate orders for their being enforced both in Spain and in the Netherlands. In Spain the decrees were received as a matter of course, the council having authority over the Catholic people; but the attempt to force the mandates of an ecclesiastical body upon a people who neither acknowledged its authority nor believed in its truth, was justly regarded as an outrage, and the whole country burst out in a storm of indignation. In many places the decrees were not executed at all; and wherever the authorities did attempt to execute them, the people rose and compelled them to desist.

A political club or confederacy was organized among the nobility for the express purpose of resisting the establishment of the Inquisition. They bound themselves by a solemn oath “to oppose the introduction of the Inquisition, whether it were attempted openly or secretly, or by whatever name it should be called,” and also to protect and defend each other from all the consequences which might result from their having formed this league.

Perplexed and alarmed, the regent implored the Prince of Orange and his two associates, Counts Egmont and Horn, to return to the council and give her their advice. They did so; and a speech of the Prince of Orange, in which he asserted strongly the utter folly of attempting to suppress opinion by force, and argued that “such is the nature of heresy that if it rests it rusts, but whoever rubs it whets it,” had the effect of inclining the regent to mitigate the ferocity of her former edicts. Meanwhile the confederates were becoming bolder and more numerous. Assembling in great numbers at Brussels, they walked in procession through the streets to the palace of the regent, where they were admitted to an interview. In reply to their petition, she said she was willing to send one or more persons to Spain to lay the complaint before the king.