Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Curious Myths of the Middle Ages, by S. Baring-Gould (published 1867). All spelling in the original.

Ragged, bald, and desolate, as though a curse rested upon it, rises the Hörselberg out of the rich and populous land between Eisenach and Gotha, looking, from a distance, like a huge stone sarcophagus—a sarcophagus in which rests in magical slumber, till the end of all things, a mysterious world of wonders.

High up on the north-west flank of the mountain, in a precipitous wall of rock, opens a cavern, called the Hörselloch, from the depths of which issues a muffled roar of water, as though a subterraneous stream were rushing over rapidly-whirling millwheels. “When I have stood alone on the ridge of the mountain,” says Bechstein, “after having sought the chasm in vain, I have heard a mighty rush, like that of falling water, beneath my feet, and after scrambling down the scarp, have found myself—how, I never knew—in front of the cave.” (“Sagenschatz des Thüringes-landes,” 1835.)

In ancient days, according to the Thüringian Chronicles, bitter cries and long-drawn moans were heard issuing from this cavern; and at night, wild shrieks and the burst of diabolical laughter would ring from it over the vale, and fill the inhabitants with terror. It was supposed that this hole gave admittance to Purgatory; and the popular but faulty derivation of Hörsel was Höre, die Seele—Hark, the Souls!

But another popular belief respecting this mountain was, that in it Venus, the pagan Goddess of Love, held her court, in all the pomp and revelry of heathendom; and there were not a few who declared that they had seen fair forms of female beauty beckoning them from the mouth of the chasm, and that they had heard dulcet strains of music well up from the abyss above the thunder of the falling, unseen torrent. Charmed by the music, and allured by the spectral forms, various individuals had entered the cave, and none had returned, except the Tanhäuser, of whom more anon. Still does the Hörselberg go by the name of the Venusberg, a name frequently used in the middle ages, but without its locality being defined.

“In 1398, at midday, there appeared suddenly three great fires in the air, which presently ran together into one globe of flame, parted again, and finally sank into the Hörselberg,” says the Thüringian Chronicle.

And now for the story of Tanhäuser.

A French knight was riding over the beauteous meadows in the Hörsel vale on his way to Wartburg, where the Landgrave Hermann was holding a gathering of minstrels, who were to contend in song for a prize.

Tanhäuser was a famous minnesinger, and all his lays were of love and of women, for his heart was full of passion, and that not of the purest and noblest description.

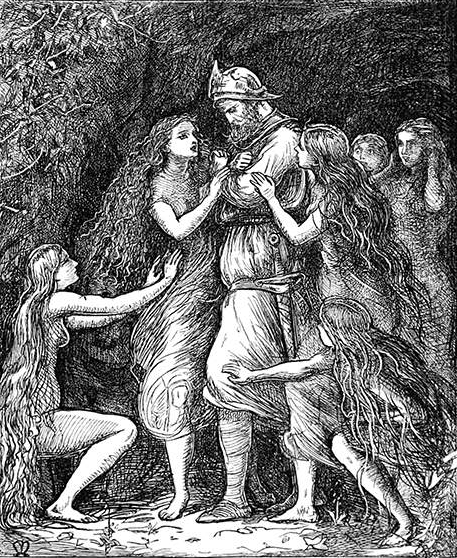

It was towards dusk that he passed the cliff in which is the Hörselloch, and as he rode by, he saw a white glimmering figure of matchless beauty standing before him, and beckoning him to her. He knew her at once, by her attributes and by her superhuman perfection, to be none other than Venus. As she spake to him, the sweetest strains of music floated in the air, a soft roseate light glowed around her, and nymphs of exquisite loveliness scattered roses at her feet. A thrill of passion ran through the veins of the minnesinger; and, leaving his horse, he followed the apparition. It led him up the mountain to the cave, and as it went flowers bloomed upon the soil, and a radiant track was left for Tanhäuser to follow. He entered the cavern, and descended to the palace of Venus in the heart of the mountain.

Seven years of revelry and debauch were passed, and the minstrel’s heart began to feel a strange void. The beauty, the magnificence, the variety of the scenes in the pagan goddess’s home, and all its heathenish pleasures, palled upon him, and he yearned for the pure fresh breezes of earth, one look up at the dark night sky spangled with stars, one glimpse of simple mountain-flowers, one tinkle of sheep-bells. At the same time his conscience began to reproach him, and he longed to make his peace with God. In vain did he entreat Venus to permit him to depart, and it was only when, in the bitterness of his grief, he called upon the Virgin-Mother, that a rift in the mountain-side appeared to him, and he stood again above ground.

How sweet was the morning air, balmy with the scent of hay, as it rolled up the mountain to him, and fanned his haggard cheek! How delightful to him was the cushion of moss and scanty grass after the downy couches of the palace of revelry below! He plucked the little heather-bells, and held them before him; the tears rolled from his eyes, and moistened his thin and wasted hands. He looked up at the soft blue sky and the newly-risen sun, and his heart overflowed. What were the golden, jewel-incrusted, lamp-lit vaults beneath to that pure dome of God’s building!

The chime of a village church struck sweetly on his ear, satiated with Bacchanalian songs; and he hurried down the mountain to the church which called him. There he made his confession; but the priest, horror-struck at his recital, dared not give him absolution, but passed him on to another. And so he went from one to another, till at last he was referred to the Pope himself. To the Pope he went. Urban IV then occupied the chair of St. Peter. To him Tanhäuser related the sickening story of his guilt, and prayed for absolution. Urban was a hard and stern man, and shocked at the immensity of the sin, he thrust the penitent indignantly from him, exclaiming, “Guilt such as thine can never, never be remitted. Sooner shall this staff in my hand grow green and blossom, than that God should pardon thee!”

Then Tanhäuser, full of despair, and with his soul darkened, went away, and returned to the only asylum open to him, the Venusberg. But lo! three days after he had gone, Urban discovered that his pastoral staff had put forth buds, and had burst into flower. Then he sent messengers after Tanhäuser, and they reached the Hörsel vale to hear that a wayworn man, with haggard brow and bowed head, had just entered the Hörselloch. Since then Tanhäuser has not been seen.

Such is the sad yet beautiful story of Tanhäuser. It is a very ancient myth Christianized, a wide-spread tradition localized. Originally heathen, it has been transformed, and has acquired new beauty by an infusion of Christianity. Scattered over Europe, it exists in various forms, but in none so graceful as that attached to the Hörselberg. There are, however, other Venusbergs in Germany; as, for instance, in Swabia, near Waldsee; another near Ufhausen, at no great distance from Freiburg (the same story is told of this Venusberg as of the Hörselberg); in Saxony there is a Venusberg not far from Wolkenstein. Paracelsus speaks of a Venusberg in Italy, referring to that in which Æneas Sylvius (Ep. 16) says Venus or a Sibyl resides, occupying a cavern, and assuming once a week the form of a serpent. Geiler v. Keysersperg, a quaint old preacher of the fifteenth century, speaks of the witches assembling on the Venusberg.

The story, either in prose or verse, has often been printed. Some of the earliest editions are the following:—

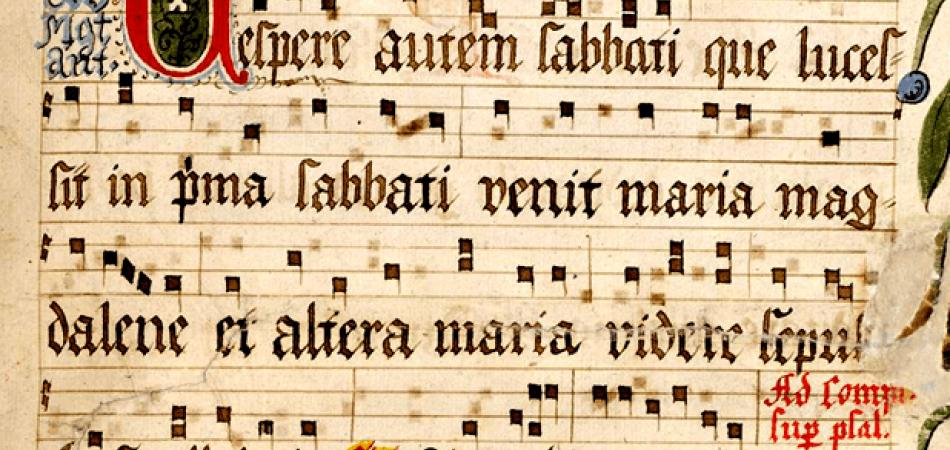

“Das Lied von dem Danhewser.” Nürnberg, without date; the same, Nürnberg, 1515.—“Das Lyedt v. d. Thanheuser.” Leyptzk, 1520.—“Das Lied v. d. Danheüser,” reprinted by Bechstein, 1835.—“Das Lied vom edlen Tanheuser, Mons Veneris.” Frankfort, 1614; Leipzig, 1668.—“Twe lede volgen Dat erste vain Danhüsser.” Without date.—“Van heer Danielken.” Tantwerpen, 1544.—A Danish version in “Nyerup, Danske Viser,” No. VIII.

Let us now see some of the forms which this remarkable myth assumed in other countries. Every popular tale has its root, a root which may be traced among different countries, and though the accidents of the story may vary, yet the substance remains unaltered. It has been said that the common people never invent new story-radicals any more than we invent new word-roots; and this is perfectly true. The same story-root remains, but it is varied according to the temperament of the narrator or the exigencies of localization. The story-root of the Venusberg is this:—

The underground folk seek union with human beings.

α. A man is enticed into their abode, where he unites with a woman of the underground race.

β. He desires to revisit the earth, and escapes.

γ. He returns again to the region below.

Now, there is scarcely a collection of folk-lore which does not contain a story founded on this root. It appears in every branch of the Aryan family, and examples might be quoted from Modern Greek, Albanian, Neapolitan, French, German, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, Icelandic, Scotch, Welsh, and other collections of popular tales. I have only space to mention some.

There is a Norse Tháttr of a certain Helgi Thorir’s son, which is, in its present form, a production of the fourteenth century. Helgi and his brother Thorstein went on a cruise to Finnmark, or Lapland. They reached a ness, and found the land covered with forest. Helgi explored this forest, and lighted suddenly on a party of red-dressed women riding upon red horses. These ladies were beautiful and of troll race. One surpassed the others in beauty, and she was their mistress. They erected a tent and prepared a feast. Helgi observed that all their vessels were of silver and gold. The lady, who named herself Ingibjorg, advanced towards the Norseman, and invited him to live with her. He feasted and lived with the trolls for three days, and then returned to his ship, bringing with him two chests of silver and gold, which Ingibjorg had given him. He had been forbidden to mention where he had been and with whom; so he told no one whence he had obtained the chests. The ships sailed, and he returned home.

One winter’s night Helgi was fetched away from home, in the midst of a furious storm, by two mysterious horsemen, and no one was able to ascertain for many years what had become of him, till the prayers of the king, Olaf, obtained his release, and then he was restored to his father and brother, but he was thenceforth blind. All the time of his absence he had been with the red-vested lady in her mysterious abode of Glœsisvellir.

The Scotch story of Thomas of Ercildoune is the same story. Thomas met with a strange lady, of elfin race, beneath Eildon Tree, who led him into the underground land, where he remained with her for seven years. He then returned to earth, still, however, remaining bound to come to his royal mistress whenever she should summon him. Accordingly, while Thomas was making merry with his friends in the Tower of Ercildoune, a person came running in, and told, with marks of fear and astonishment, that a hart and a hind had left the neighboring forest, and were parading the street of the village. Thomas instantly arose, left his house, and followed the animals into the forest, from which he never returned. According to popular belief, he still “drees his weird” in Fairy Land, and is one day expected to revisit earth. (Scott, “Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.”) Compare with this the ancient ballad of Tamlane.

Debes relates that “it happened a good while since, when the burghers of Bergen had the commerce of the Faroe Isles, that there was a man in Serraade, called Jonas Soideman, who was kept by the spirits in a mountain during the space of seven years, and at length came out, but lived afterwards in great distress and fear, lest they should again take him away; wherefore people were obliged to watch him in the night.” The same author mentions another young man who had been carried away, and after his return was removed a second time, upon the eve of his marriage.

Gervase of Tilbury says that “in Catalonia there is a lofty mountain, named Cavagum, at the foot of which runs a river with golden sands, in the vicinity of which there are likewise silver mines. This mountain is steep, and almost inaccessible. On its top, which is always covered with ice and snow, is a black and bottomless lake, into which if a stone be cast, a tempest suddenly arises; and near this lake is the portal of the palace of demons.” He then tells how a young damsel was spirited in there, and spent seven years with the mountain spirits. On her return to earth she was thin and withered, with wandering eyes, and almost bereft of understanding.

A Swedish story is to this effect. A young man was on his way to his bride, when he was allured into a mountain by a beautiful elfin woman. With her he lived forty years, which passed as an hour; on his return to earth all his old friends and relations were dead, or had forgotten him, and finding no rest there, he returned to his mountain elf-land.

In Pomerania, a laborer’s son, Jacob Dietrich of Rambin, was enticed away in the same manner.

There is a curious story told by Fordun in his “Scotichronicon,” which has some interest in connection with the legend of the Tanhäuser. He relates that in the year 1050, a youth of noble birth had been married in Rome, and during the nuptial feast, being engaged in a game of ball, he took off his wedding-ring, and placed it on the finger of a statue of Venus. When he wished to resume it, he found that the stony hand had become clinched, so that it was impossible to remove the ring. Thenceforth he was haunted by the Goddess Venus, who constantly whispered in his ear, “Embrace me; I am Venus, whom you have wedded; I will never restore your ring.” However, by the assistance of a priest, she was at length forced to give it up to its rightful owner.

The classic legend of Ulysses, held captive for eight years by the nymph Calypso in the Island of Ogygia, and again for one year by the enchantress Circe, contains the root of the same story of the Tanhäuser.

What may have been the significance of the primeval story-radical it is impossible for us now to ascertain; but the legend, as it shaped itself in the middle ages, is certainly indicative of the struggle between the new and the old faith.

We see thinly veiled in Tanhäuser the story of a man, Christian in name, but heathen at heart, allured by the attractions of paganism, which seems to satisfy his poetic instincts, and which gives full rein to his passions. But these excesses pall on him after a while, and the religion of sensuality leaves a great void in his breast.

He turns to Christianity, and at first it seems to promise all that he requires. But alas! he is repelled by its ministers. On all sides he is met by practice widely at variance with profession. Pride, worldliness, want of sympathy exist among those who should be the foremost to guide, sustain, and receive him. All the warm springs which gushed up in his broken heart are choked, his softened spirit is hardened again, and he returns in despair to bury his sorrows and drown his anxieties in the debauchery of his former creed.

A sad picture, but doubtless one very true.

3.5

5