Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, Vol. 5, by Charles Morris (published 1893).

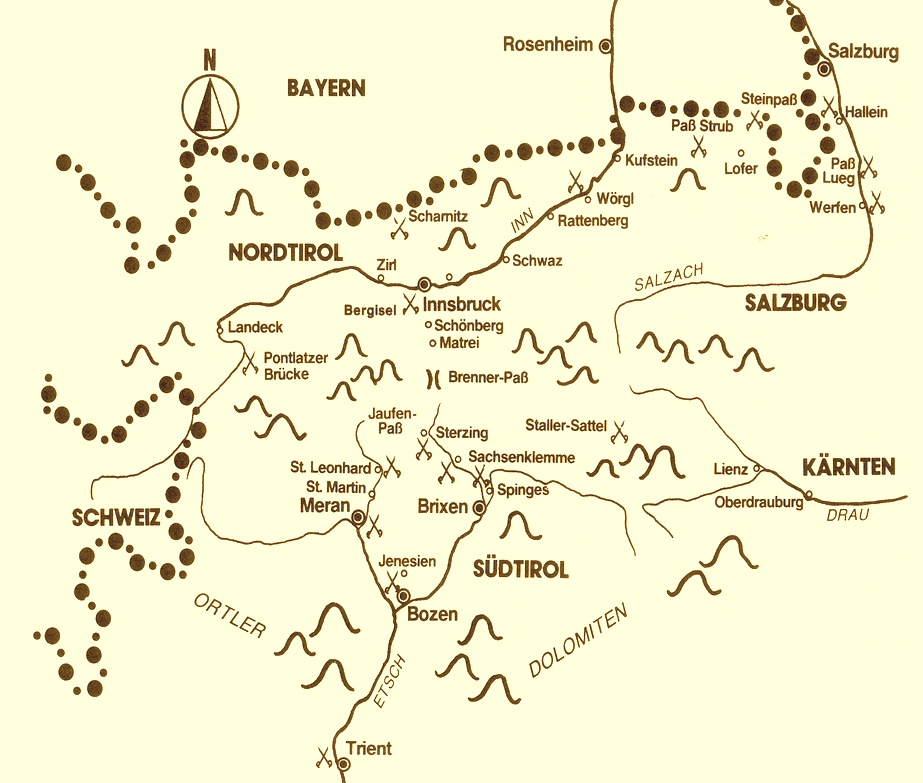

On the 9th of April, 1809, down the river Inn, in the Tyrol, came floating a series of planks, from whose surface waved little red flags. What they meant the Bavarian soldiers, who held that mountain land with a hand of iron, could not conjecture. But what they meant the peasantry well knew. On the day before peace had ruled throughout the Alps, and no Bavarian dreamed of war. Those flags were the signal for insurrection, and on their appearance the brave mountaineers sprang at once to arms and flew to the defense of the bridges of their country, which the Bavarians were marching to destroy, as an act of defense against the Austrians.

On the 10th the storm of war burst. Some Bavarian sappers had been sent to blow up the bridge of St. Lorenzo. But hardly had they begun their work, when a shower of bullets from unseen marksmen swept the bridge. Several were killed; the rest took to flight; the Tyrol was in revolt.

News of this outbreak was borne to Colonel Wrede, in command of the Bavarians, who hastened with a force of infantry, cavalry, and artillery to the spot. He found the peasants out in numbers. The Tyrolean riflemen, who were accustomed to bring down chamois from the mountain peaks, defended the bridge, and made terrible havoc in the Bavarian ranks. They seized Wrede’s artillery and flung guns and gunners together into the stream, and finally put the Bavarians to rout, with severe loss.

The Bavarians held the Tyrol as allies of the French, and the movement against the bridges had been directed by Napoleon, to prevent the Austrians from reoccupying the country, which had been wrested from their hands. Wrede in his retreat was joined by a body of three thousand French, but decided, instead of venturing again to face the daring foe, to withdraw to Innsbruck. But withdrawal was not easy. The signal of revolt had everywhere called the Tyrolese to arms. The passes were occupied. The fine old Roman bridge over the Brenner, at Laditsch, was blown up. In the pass of the Brixen, leading to this bridge, the French and Bavarians found themselves assailed in the old Swiss manner, by rocks and logs rolled down upon their heads, while the unerring rifles of the hidden peasants swept the pass. Numbers were slain, but the remainder succeeded in escaping by means of a temporary bridge, which they threw over the stream on the site of the bridge of Laditsch.

Of the Tyrolese patriots to whom this outbreak was due two are worthy of special mention, Joseph Speckbacher, a wealthy peasant of Rinn, and the more famous Andrew Hofer, the host of the Sand Inn at Passeyr, a man everywhere known through the mountains, as he traded in wine, corn, and horses as far as the Italian frontier.

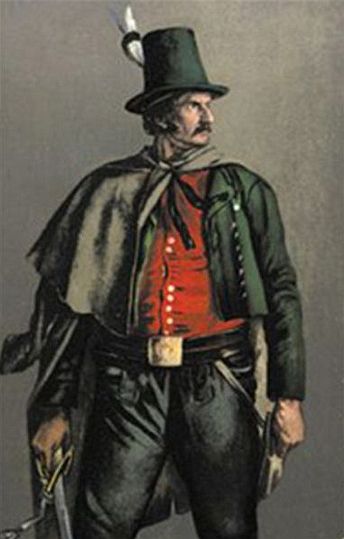

Hofer was a man of herculean frame and of a full, open, handsome countenance, which gained dignity from its long, dark-brown beard, which fell in rich curls upon his chest. His picturesque dress—that of the Tyrol—comprised a red waistcoat, crossed by green braces, which were fastened to black knee breeches of chamois leather, below which he wore red stockings. A broad black leather girdle clasped his muscular form, while over all was worn a short green coat. On his head he wore a low-crowned, broad-brimmed Tyrolean hat, black in color, and ornamented with green ribbons and with the feathers of the capercailzie.

This striking-looking patriot, at the head of a strong party of peasantry, made an assault, early on the 11th, upon a Bavarian infantry battalion under the command of Colonel Bäraklau, who retreated to a table-land named Sterzinger Moos, where, drawn up in a square, he resisted every effort of the Tyrolese to dislodge him. Finally Hofer broke his lines by a stratagem. A wagon loaded with hay, and driven by a girl, was pushed towards the square, the brave girl shouting, as the balls flew around her, “On with ye! Who cares for Bavarian dumplings!” Under its shelter the Tyrolese advanced, broke the square, and killed or made prisoners the whole of the battalion.

Speckbacher, the other patriot named, was no less active. No sooner had the signal of revolt appeared in the Inn than he set the alarm-bells ringing in every church-tower through the lower valley of that stream, and quickly was at the head of a band of stalwart Tyrolese. On the night of the 11th he advanced on the city of Hall, and lighted about a hundred watch-fires on one side of the city, as if about to attack it from that quarter. While the attention of the garrison was directed towards these fires, he crept through the darkness to the gate on the opposite side, and demanded entrance as a common traveler. The gate was opened; his hidden companions rushed forward and seized it; in a brief time the city, with its Bavarian garrison, was his.

On the 12th he appeared before Innsbruck, and made a fierce assault upon the city in which he was aided by a murderous fire poured upon the Bavarians by the citizens from windows and towers. The people of the upper valley of the Inn flocked to the aid of their fellows, and the place, with its garrison, was soon taken, despite their obstinate defense. Dittfurt, the Bavarian leader, who scornfully refused to yield to the peasant dogs, as he considered them, fought with tiger-like ferocity, and fell at length, pierced by four bullets.

One further act completed the freeing of the Tyrol from Bavarian domination. The troops under Colonel Wrede had, as we have related, crossed the Brenner on a temporary bridge, and escaped the perils of the pass. Greater perils awaited them. Their road lay past Sterzing, the scene of Hofer’s victory. Every trace of the conflict had been obliterated, and Wrede vainly sought to discover what had become of Bäraklau and his battalion. He entered the narrow pass through which the road ran at that place, and speedily found his ranks decimated by the rifles of Hofer’s concealed men.

After considerable loss the column broke through, and continued its march to Innsbruck, where it was immediately surrounded by a triumphant host of Tyrolese. The struggle was short, sharp, and decisive. In a few minutes several hundred men had fallen. In order to escape complete destruction the rest laid down their arms. The captors entered Innsbruck in triumph, preceded by the military band of the enemy, which they compelled to play, and guarding their prisoners, who included two generals, more than a hundred other officers, and about two thousand men.

In two days the Tyrol had been freed from its Bavarian oppressors and their French allies and restored to its Austrian lords. The arms of Bavaria were everywhere cast to the ground, and the officials removed. But the prisoners were treated with great humanity, except in the single instance of a tax-gatherer, who had boasted that he would grind down the Tyrolese until they should gladly eat hay. In revenge, they forced him to swallow a bushel of hay for his dinner.

In two days the Tyrol had been freed from its Bavarian oppressors and their French allies and restored to its Austrian lords. The arms of Bavaria were everywhere cast to the ground, and the officials removed. But the prisoners were treated with great humanity, except in the single instance of a tax-gatherer, who had boasted that he would grind down the Tyrolese until they should gladly eat hay. In revenge, they forced him to swallow a bushel of hay for his dinner.

The freedom thus gained by the Tyrolese was not likely to be permanent with Napoleon for their foe. The Austrians hastened to the defense of the country which had been so bravely won for their emperor. On the other side came the French and Bavarians as enemies and oppressors. Lefebvre, the leader of the invaders, was a rough and brutal soldier, who encouraged his men to commit every outrage upon the mountaineers.

For some two or three months the conflict went on, with varying fortunes, depending upon the conditions of the war between France and Austria. At first the French were triumphant, and the Austrians withdrew from the Tyrol. Then came Napoleon’s defeat at Aspern, and the Tyrolese rose and again drove the invaders from their country. In July occurred Napoleon’s great victory at Wagram, and the hopes of the Tyrol once more sank. All the Austrians were withdrawn, and Lefebvre again advanced at the head of thirty or forty thousand French, Bavarians, and Saxons.

The courage of the peasantry vanished before this threatening invasion. Hofer alone remained resolute, saying to the Austrian governor, on his departure, “Well, then, I will undertake the government, and, as long as God wills, name myself Andrew Hofer, host of the Sand at Passeyr, and Count of the Tyrol.”

He needed resolution, for his fellow-chiefs deserted the cause of their country on all sides. On his way to his home he met Speckbacher, hurrying from the country in a carriage with some Austrian officers.

“Wilt thou also desert thy country!” said Hofer to him in tones of sad reproach.

Another leader, Joachim Haspinger, a Capuchin monk, nicknamed Redbeard, a man of much military talent, withdrew to his monastery at Seeben. Hofer was left alone of the Tyrolese leaders. While the French advanced without opposition, he took refuge in a cavern amid the steep rocks that overhung his native vale, where he implored Heaven for aid.

The aid came. Lefebvre, in his brutal fashion, plundered and burnt as he advanced, and published a proscription list instead of the amnesty promised. The natural result followed. Hofer persuaded the bold Capuchin to leave his monastery, and he, with two others, called the western Tyrol to arms. Hofer raised the eastern Tyrol. They soon gained a powerful associate in Speckbacher, who, conscience-stricken by Hofer’s reproach, had left the Austrians and hastened back to his country. The invader’s cruelty had produced its natural result. The Tyrol was once more in full revolt.

With a bunch of rosemary, the gift of their chosen maidens, in their green hats, the young men grasped their trusty rifles and hurried to the places of rendezvous. The older men wore peacock plumes, the Hapsburg symbol. With haste they prepared for the war. Cannon which did good service were made from bored logs of larch wood, bound with iron rings. Here the patriots built abatis; there they gathered heaps of stone on the edges of precipices which rose above the narrow vales and passes. The timber slides in the mountains were changed in their course so that trees from the heights might be shot down upon the important passes and bridges. All that could be done to give the invaders a warm welcome was prepared, and the bold peasants waited eagerly for the coming conflict.

From four quarters the invasion came, Lefebvre’s army being divided so as to attack the Tyrolese from every side, and meet in the heart of the country. They were destined to a disastrous repulse. The Saxons, led by Rouyer, marched through the narrow valley of Eisach, the heights above which were occupied by Haspinger the Capuchin and his men. Down upon them came rocks and trees from the heights. Rouyer was hurt, and many of his men were slain around him. He withdrew in haste, leaving one regiment to retain its position in the Oberau. This the Tyrolese did not propose to permit. They attacked the regiment on the next day, in the narrow valley, with overpowering numbers. Though faint with hunger and the intense heat, and exhausted by the fierceness of the assault, a part of the troops cut their way through with great loss and escaped. The rest were made prisoners.

The story is told that during their retreat, and when ready to drop with fatigue, the soldiers found a cask of wine. Its head was knocked in by a drummer, who, as he stooped to drink, was pierced by a bullet, and his blood mingled with the wine. Despite this, the famishing soldiery greedily swallowed the contents of the cask.

A second corps d’armee advanced up the valley of the Inn as far as the bridges of Pruz. Here it was repulsed by the Tyrolese, and retreated under cover of the darkness during the night of August 8. The infantry crept noiselessly over the bridge of Pontlaz. The cavalry followed with equal caution but with less success. The sound of a horse’s hoof aroused the watchful Tyrolese. Instantly rocks and trees were hurled upon the bridge, men and horses being crushed beneath them and the passage blocked. All the troops which had not crossed were taken prisoners. The remainder were sharply pursued, and only a handful of them escaped.

The other divisions of the invading army met with a similar fate. Lefebvre himself, who reproached the Saxons for their defeat, was not able to advance as far as they, and was quickly driven from the mountains with greatly thinned ranks. He was forced to disguise himself as a common soldier and hide among the cavalry to escape the balls of the sharp-shooters, who owed him no love. The rear-guard was attacked with clubs by the Capuchin and his men, and driven out with heavy loss. During the night that followed all the mountains around the beautiful valley of Innsbruck were lit up with watch-fires. In the valley below those of the invaders were kept brightly burning while the troops silently withdrew. On the next day the Tyrol held no foes; the invasion had failed.

Hofer placed himself at the head of the government at Innsbruck, where he lived in his old simple mode of life, proclaimed some excellent laws, and convoked a national assembly. The Emperor of Austria sent him a golden chain and three thousand ducats. He received them with no show of pride, and returned the following naive answer: “Sirs, I thank you. I have no news for you to-day. I have, it is true, three couriers on the road, the Watscher-Hiesele, the Sixten-Seppele, and the Memmele-Franz, and the Schwanz ought long to have been here. I expect the rascal every hour.”

Meanwhile, Speckbacher and the Capuchin kept up hostilities successfully on the eastern frontier. Haspinger wished to invade the country of their foes, but was restrained by his more prudent associate. Speckbacher is described as an open-hearted, fine-spirited fellow, with the strength of a giant, and the best marksman in the country. So keen was his vision that he could distinguish the bells on the necks of the cattle at the distance of half a mile.

His son Anderle, but ten years of age, was of a spirit equal to his own. In one of the earlier battles of the war he had occupied himself during the fight in collecting the enemy’s balls in his hat, and so obstinately refused to quit the field that his father had him carried by force to a distant alp. During the present conflict, Anderle unexpectedly appeared and fought by his father’s side. He had escaped from his mountain retreat. It proved an unlucky escape. Shortly afterwards, the father was surprised by treachery and found himself surrounded with foes, who tore from him his arms, flung him to the ground, and seriously injured him with blows from a club. But in an instant more he sprang furiously to his feet, hurled his assailants to the earth, and escaped across a wall of rock impassable except to an expert mountaineer. A hundred of his men followed him, but his young son was taken captive by his foes. The king, Maximilian Joseph, attracted by the story of his courage and beauty, sent for him and had him well educated.

The freedom of the Tyrol was not to last long. The treaty of Vienna, between the Emperors of Austria and France, was signed. It did not even mention the Tyrol. It was a tacit understanding that the mountain country was to be restored to Bavaria, and to reduce it to obedience three fresh armies crossed its frontiers. They were repulsed in the south, but in the north Hofer, under unwise advice, abandoned the anterior passes, and the invaders made their way as far as Innsbruck, whence they summoned him to capitulate.

During the night of October 30 an envoy from Austria appeared in the Tyrolese camp, bearing a letter from the Archduke John, in which he announced the conclusion of peace and commanded the mountaineers to disperse, and not to offer their lives as a useless sacrifice. The Tyrolese regarded him as their lord, and obeyed, though with bitter regret. A dispersion took place, except of the band of Speckbacher, which held its ground against the enemy until the 3rd of November, when he received a letter from Hofer saying, “I announce to you that Austria has made peace with France, and has forgotten the Tyrol.” On receiving this news he disbanded his followers, and all opposition ceased.

The war was soon afoot again, however, in the native vale of Hofer, the people of which, made desperate by the depredations of the Italian bands which had penetrated their country, sprang to arms and resolved to defend themselves to the bitter end. They compelled Hofer to place himself at their head.

For a time they were successful. But a traitor guided the enemy to their rear, and defeat followed. Hofer escaped and took refuge among the mountain peaks. Others of the leaders were taken and executed. The most gallant among the peasantry were shot or hanged. There was some further opposition, but the invaders pressed into every valley and disarmed the people, the bulk of whom obeyed the orders given them and offered no resistance. The revolt was quelled.

Hofer took refuge at first, with his wife and child, in a narrow hollow in the Kellerlager. This he soon left for a hut on the highest alps. He was implored to leave the country, but he vowed that he would live or die on his native soil. Discovery soon came. A peasant named Raffel learned the location of his hiding-place by seeing the smoke ascend from his distant hut. He foolishly boasted of his knowledge; his story came to the ears of the French; he was arrested, and compelled to guide them to the spot. Two thousand French were spread around the mountain; a thousand six hundred ascended it; Hofer was taken.

His captors treated him with brutal violence. They tore out his beard, and dragged him pinioned, barefoot, and in his night-dress, over ice and snow to the valley. Here he was placed in a carriage and carried to the fortress of Mantua, in Italy. Napoleon, on news of the capture being brought to him at Paris, sent orders to shoot him within twenty-four hours.

He died as bravely as he had lived. When placed before the firing-party of twelve riflemen, he refused either to kneel or to allow himself to be blindfolded. “I stand before my Creator,” he exclaimed, in firm tones, “and standing will I restore to him the spirit he gave.”

He gave the signal to fire, but the men, moved by the scene, missed their aim. The first fire brought him to his knees, the second stretched him on the ground, where a corporal terminated the cruel scene by shooting him through the head. He died February 20, 1810. At a later date his remains were borne back to his native Alps, a handsome monument of white marble was erected to his memory in the church at Innsbruck, and his family was ennobled.

Of the two other principal leaders of the Tyrolese, Haspinger, the Capuchin, escaped to Vienna, which Speckbacher also succeeded in reaching, after a series of perils and escapes which are well worth relating.

After the dispersal of his troops he, like Hofer, sought concealment in the mountains where the Bavarians sought for him in troops, vowing to “cut his skin into boot-straps if they caught him.” He attempted to follow the mountain paths to Austria, but at Dux found the roads so blocked with snow that further progress was impossible. Here the Bavarians came upon his track and attacked the house in which he had taken refuge. He escaped by leaping from its roof, but was wounded in doing so.

For the twenty-seven days that followed he roamed through the snowy mountain forests, in danger of death both from cold and starvation. Once for four days together he did not taste food. At the end of this time he found shelter in a hut at Bolderberg, where by chance he found his wife and children, who had sought the same asylum.

His bitterly persistent foes left him not long in safety here. They learned his place of retreat, and pursued him, his presence of mind alone saving him from capture. Seeing them approach, he took a sledge upon his shoulders, and walked towards and past them as though he were a servant of the house.

His next place of refuge was in a cave on the Gemshaken, in which he remained until the opening of spring, when he had the ill-fortune to be carried by a snow-slide a mile and a half into the valley. It was impossible to return. He crept from the snow, but found that one of his legs was dislocated. The utmost he could do, and that with agonizing pain, was to drag himself to a neighboring hut. Here were two men, who carried him to his own house at Rinn.

Bavarians were quartered in the house, and the only place of refuge open to him was the cow-shed, where his faithful servant Zoppel dug for him a hole beneath the bed of one of the cows, and daily supplied him with food. His wife had returned to the house, but the danger of discovery was so great that even she was not told of his propinquity.

For seven weeks he remained thus half buried in the cow-shed, gradually recovering his strength. At the end of that time he rose, bade adieu to his wife, who now first learned of his presence, and again betook himself to the high paths of the mountains, from which the sun of May had freed the snow. He reached Vienna without further trouble.

Here the brave patriot received no thanks for his services. Even a small estate he had purchased with the remains of his property he was forced to relinquish, not being able to complete the purchase. He would have been reduced to beggary but for Hofer’s son, who had received a fine estate from the emperor, and who engaged him as his steward. Thus ended the active career of the ablest leader in the Tyrolean war.

4.5

5