Editor’s note: Here follows the seventeenth chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XVII: MILITARY OBSERVATIONS

"... And thou hast talk'd

Of sallies and retires, of trenches, tents,

Of palisadoes, frontiers, parapets,

Of basilisks, of cannon, culverin."

"Henry IV.," Part I., Act ii., Sc.3.

It may at first seem that a chapter wholly devoted to military considerations is inappropriate to a book which, if it is to enjoy any measure of success, must be read by many unconnected with the army. But I remember that in these days it is necessary for every one, who means to be well informed, to have a superficial knowledge of every one else’s business. Encouraged also by what Mr. Gladstone has called “the growing militarism of the times,” I hope that, avoiding technicalities, it may be of some general interest to glance for a moment at the frontier war from a purely professional point of view. My observations must be taken as applying to the theatre of the war I have described, but I do not doubt that many of them will be applicable to the whole frontier.

The first and most important consideration is transport. Nobody who has not seen for himself can realise what a great matter this is. I well recall my amazement, when watching a camel convoy more than a mile and a half long, escorted by half a battalion of infantry. I was informed that it contained only two days’ supplies for one brigade. People talk lightly of moving columns hither and thither, as if they were mobile groups of men, who had only to march about the country and fight the enemy wherever found, and very few understand that an army is a ponderous mass which drags painfully after it a long chain of advanced depots, stages, rest camps, and communications, by which it is securely fastened to a stationary base. In these valleys, where wheeled traffic is impossible, the difficulties and cost of moving supplies are enormous; and as none, or very few, are to be obtained within the country, the consideration is paramount. Mule transport is for many reasons superior to camel transport. The mule moves faster and can traverse more difficult ground. He is also more hardy and keeps in better condition. When Sir Bindon Blood began his advance against the Mohmands he equipped his 2nd Brigade entirely with mules. It was thus far more mobile, and was available for any rapid movement that might become necessary. To mix the two—camels and mules—appears to combine the disadvantages of both, and destroy the superiority of either.

I have already described the Indian service camp and the “sniping” without which no night across the frontier could be complete. I shall therefore only notice two points, which were previously omitted, as they looked suspiciously technical. As the night firing is sometimes varied by more serious attacks, and even actual assaults and sword rushes, it is thought advisable to have the ditch of the entrenchment towards the enemy. Modern weapons notwithstanding, the ultimate appeal is to the bayonet, and the advantage of being on the higher ground is then considerable.

When a battery forms part of the line round a camp, infantry soldiers should be placed between the guns. Artillery officers do not like this; but, though they are very good fellows, there are some things in which it is not well to give way to them. Every one is prone to over-estimate the power of his arm.

In the Mamund Valley all the fighting occurred in capturing villages, which lay in rocky and broken ground in the hollows of the mountains, and were defended by a swarm of active riflemen. Against the quickly moving figures of the enemy it proved almost useless to fire volleys. The tribesmen would dart from rock to rock, exposing themselves only for an instant, and before the attention of a section could be directed to them and the rifles aimed, the chance and the target would have vanished together. Better results were obtained by picking out good shots and giving them permission to fire when they saw their opportunity, without waiting for the word of command. But speaking generally, infantry should push on to the attack with the bayonet without wasting much time in firing, which can only result in their being delayed under the fire of a well-posted enemy.

After the capture and destruction of the village, the troops had always to return to camp, and a retirement became necessary. The difficulty of executing such an operation in the face of an active and numerous enemy, armed with modern rifles, was great. I had the opportunity of witnessing six of these retirements from the rear companies. Five were fortunate and one was disastrous, but all were attended with loss, and as experienced officers have informed me, with danger. As long as no one is hit everything is successful, but as soon as a few men are wounded, the difficulties begin. No sooner has a point been left—a knoll, a patch of corn, some rocks, or any other incident of ground—than it is seized by the enemy. With their excellent rifles, they kill or wound two or three of the retiring company, whose somewhat close formation makes them a good mark. Now, in civilised war these wounded would be left on the ground, and matters arranged next day by parley. But on the frontier, where no quarter is asked or given, to carry away the wounded is a sacred duty. It is also the strenuous endeavour of every regiment to carry away their dead. The vile and horrid mutilations which the tribesmen inflict on all bodies that fall into their hands, and the insults to which they expose them, add, to unphilosophic minds, another terror to death. Now, it takes at least four men, and very often more, to carry away a body. Observe the result. Every man hit, means five rifles withdrawn from the firing line. Ten men hit, puts a company out of action, as far as fighting power is concerned. The watchful enemy press. The groups of men bearing the injured are excellent targets. Presently the rear-guard is encumbered with wounded. Then a vigorous charge with swords is pushed home. Thus, a disaster occurs.

Watching the progress of events, sometimes from one regiment, sometimes from another, I observed several ways by which these difficulties could be avoided. The Guides, long skilled in frontier war, were the most valuable instructors. As the enemy seize every point as soon as it is left, all retirements should be masked by leaving two or three men behind from each company. These keep up a brisk fire, and after the whole company have taken up a new position, or have nearly done so, they run back and join them. Besides this, the fire of one company in retiring should always be arranged to cover another, and at no moment in a withdrawal should the firing ever cease. The covering company should be actually in position before the rear company begins to move, and should open fire at once. I was particularly struck on 18th September by the retirement of the Guides Infantry. These principles were carried out with such skill and thoroughness that, though the enemy pressed severely, only one man was wounded. The way in which Major Campbell, the commanding officer, availed himself of the advantages of retiring down two spurs and bringing a cross fire to bear to cover the alternate retirements, resembled some intricate chess problem, rather than a military evolution.

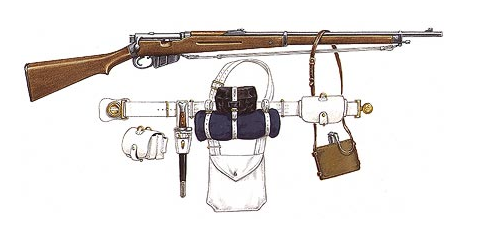

The power of the new Lee-Metford rifle with the new Dum-Dum bullet—it is now called, though not officially, the “ek-dum” [Hindustani for “at once.”] bullet—is tremendous. The soldiers who have used it have the utmost confidence in their weapon. Up to 500 yards there is no difficulty about judging the range, as it shoots quite straight, or, technically speaking, has a flat trajectory. This is of the greatest value. Of the bullet it may be said, that its stopping power is all that could be desired. The Dum-Dum bullet, though not explosive, is expansive. The original Lee-Metford bullet was a pellet of lead covered by a nickel case with an opening at the base. In the improved bullet this outer case has been drawn backward, making the hole in the base a little smaller and leaving the lead at the tip exposed. The result is a wonderful and from the technical point of view a beautiful machine. On striking a bone this causes the bullet to “set up” or spread out, and it then tears and splinters everything before it, causing wounds which in the body must be generally mortal and in any limb necessitate amputation. Continental critics have asked whether such a bullet is not a violation of the Geneva or St. Petersburg Conventions; but no clause of these international agreements forbids expansive bullets, and the only provision on the subject is that shells less than a certain size shall not be employed. I would observe that bullets are primarily intended to kill, and that these bullets do their duty most effectually, without causing any more pain to those struck by them, than the ordinary lead variety. As the enemy obtained some Lee-Metford rifles and Dum-Dum ammunition during the progress of the fighting, information on this latter point is forthcoming. The sensation is described as similar to that produced by any bullet—a violent numbing blow, followed by a sense of injury and weakness, but little actual pain at the time. Indeed, now-a-days, very few people are so unfortunate as to suffer much pain from wounds, except during the period of recovery. A man is hit. In a quarter of an hour, that is to say, before the shock has passed away and the pain begins, he is usually at the dressing station. Here he is given morphia injections, which reduce all sensations to a uniform dullness. In this state he remains until he is placed under chloroform and operated on.

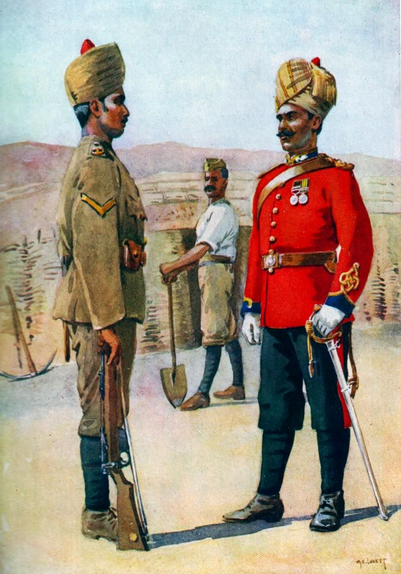

The necessity for having the officers in the same dress as the men, was apparent to all who watched the operations. The conspicuous figure which a British officer in his helmet presented in contrast to the native soldiers in their turbans, drew a well-aimed fire in his direction. Of course, in British regiments, the difference is not nearly so marked. Nevertheless, at close quarters the keen-eyed tribesmen always made an especial mark of the officers, distinguishing them chiefly, I think, by the fact that they do not carry rifles. The following story may show how evident this was:—

When the Buffs were marching down to Panjkora, they passed the Royal West Kent coming up to relieve them at Inayat Kila. A private in the up-going regiment asked a friend in the Buffs what it was like at the front. “Oh,” replied the latter, “you’ll be all right so long as you don’t go near no officers, nor no white stones.” Whether the advice was taken is not recorded, but it was certainly sound, for three days later—on 30th September—in those companies of the Royal West Kent regiment that were engaged in the village of Agrah, eight out of eleven officers were hit or grazed by bullets.

The fatigues experienced by troops in mountain warfare are so great, that every effort has to be made to lighten the soldier’s load. At the same time the more ammunition he carries on his person the better. Mules laden with cartridge-boxes are very likely to be shot, and fall into the hands of the enemy. In this manner over 6000 rounds were lost on the 16th of September by the two companies of Sikhs whose retirement I have described.

The thick leather belts, pouches, and valise equipment of British infantry are unnecessarily heavy. I have heard many officers suggest having them made of web. The argument against this is that the web wears out. That objection could be met by having a large supply of these equipments at the base and issuing fresh ones as soon as the old were unfit for use. It is cheaper to wear out belts than soldiers.

Great efforts should be made to give the soldier a piece of chocolate, a small sausage, or something portable and nutritious to carry with him to the field. In a war of long marches, of uncertain fortunes, of retirements often delayed and always pressed, there have been many occasions when regiments and companies have unexpectedly had to stop out all night without food. It is well to remember that the stomach governs the world.

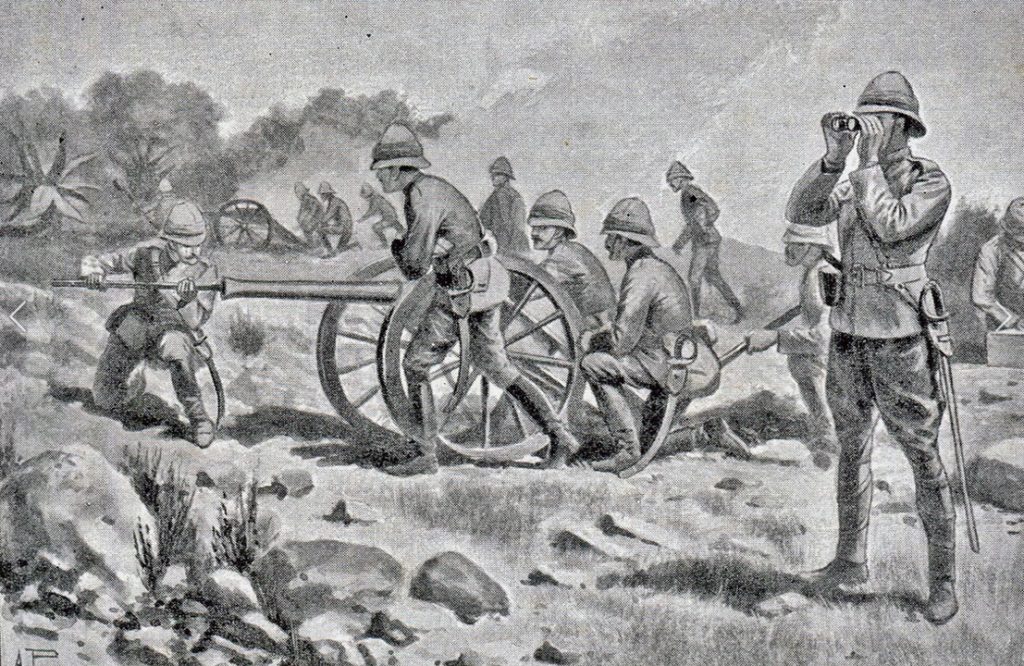

The principle of concentrating artillery has long been admitted in Europe. Sir Bindon Blood is the first general who has applied it to mountain warfare in India. It had formerly been the custom to use the guns by twos and threes. As we have seen, at the action of Landakai, the Malakand Field Force had eighteen guns in action, of which twelve were in one line. The fire of this artillery drove the enemy, who were in great strength and an excellent position, from the ground. The infantry attack was accomplished with hardly any loss, and a success was obtained at a cost of a dozen lives which would have been cheap at a hundred.

After this, it may seem strange if I say that the artillery fire in the Mamund Valley did very little execution. It is nevertheless a fact. The Mamunds are a puny tribe, but they build their houses in the rocks; and against sharpshooters in broken ground, guns can do little. Through field-glasses it was possible to see the enemy dodging behind their rocks, whenever the puffs of smoke from the guns told them that a shell was on its way. Perhaps smokeless powder would have put a stop to this. But in any case, the targets presented to the artillery were extremely bad.

Where they really were of great service, was not so much in killing the enemy, but in keeping them from occupying certain spurs and knolls. On 30th September, when the Royal West Kent and the 31st Punjaub Infantry were retiring under considerable pressure, the British Mountain Battery moved to within 700 yards of the enemy, and opened a rapid fire of shrapnel on the high ground which commanded the line of retreat, killing such of the tribesmen as were there, and absolutely forbidding the hill to their companions.

In all rearguard actions among the mountains the employment of artillery is imperative. Even two guns may materially assist the extrication of the infantry from the peaks and crags of the hillside, and prevent by timely shells the tribesmen from seizing each point as soon as it is evacuated. But there is no reason why the artillery should be stinted, and at least two batteries, if available, should accompany a brigade to the attack.

Signalling by heliograph was throughout the operations of the greatest value. I had always realised the advantages of a semi-permanent line of signal stations along the communications to the telegraph, but I had doubted the practicability of using such complicated arrangements in action. In this torrid country, where the sun is always shining, the heliograph is always useful. As soon as any hill was taken, communication was established with the brigadier, and no difficulty seemed to be met with, even while the attack was in progress, in sending messages quickly and clearly. In a country intersected by frequent ravines, over which a horse can move but slowly and painfully, it is the surest, the quickest, and indeed the only means of intercommunication. I am delighted to testify to these things, because I had formerly been a scoffer.

I have touched on infantry and artillery, and, though a previous chapter has been almost wholly devoted to the cavalry, I cannot resist the desire to get back to the horses and the lances again. The question of sword or lance as the cavalryman’s weapon has long been argued, and it may be of interest to consider what are the views of those whose experience is the most recent. Though I have had no opportunity of witnessing the use of the lance, I have heard the opinions of many officers both of the Guides and the 11th Bengal Lancers. All admit or assert that the lance is in this warfare the better weapon. It kills with more certainty and convenience, and there is less danger of the horseman being cut down. As to length, the general opinion seems to be in favour of a shorter spear. This, with a counter poise at the butt, gives as good a reach and is much more useful for close quarters. Major Beatson, one of the most distinguished cavalry officers on the frontier, is a strong advocate of this. Either the pennon should be knotted, or a boss of some sort affixed about eighteen inches below the point. Unless this be done there is a danger of the lance penetrating too far, when it either gets broken or allows the enemy to wriggle up and strike the lancer. This last actually happened on several occasions.

Now, in considering the question to what extent a squadron should be armed with lances, the system adopted by the Guides may be of interest. In this warfare it is very often necessary for the cavalryman to dismount and use his carbine. The lance then gets in the way and has to be tied to the saddle. This takes time, and there is usually not much time to spare in cavalry skirmishing. The Guides compromise matters by giving one man in every four a lance. This man, when the others dismount, stays in the saddle and holds their horses. They also give the outer sections of each squadron lances, and these, too, remain mounted, as the drill-book enjoins. But I become too technical.

I pass for a moment to combined tactics. In frontier warfare Providence is on the side of the good band-o-bust [arrangements]. There are no scenic effects or great opportunities, and the Brigadier who leaves the mountains with as good a reputation as he entered them has proved himself an able, sensible man. The general who avoids all “dash,” who never starts in the morning looking for a fight and without any definite intention, who does not attempt heroic achievements, and who keeps his eye on his watch, will have few casualties and little glory. For the enemy do not become formidable until a mistake has been made. The public who do not believe in military operations without bloodshed may be unattentive. His subordinate officers may complain that they have had no fighting. But in the consciousness of duty skillfully performed and of human life preserved he will find a high reward.

A general review of the frontier war will, I think, show the great disadvantages to which regular troops are exposed in fighting an active enterprising enemy that can move faster and shoot better, who knows the country and who knows the ranges. The terrible losses inflicted on the tribesmen in the Swat Valley show how easily disciplined troops can brush away the bravest savages in the open. But on the hillside all is changed, and the observer will be struck by the weakness rather than the strength of modern weapons. Daring riflemen, individually superior to the soldiers, and able to support the greatest fatigues, can always inflict loss, although they cannot bar their path.

The military problem with which the Spaniards are confronted in Cuba is in many points similar to that presented in the Afghan valleys; a roadless, broken and undeveloped country; an absence of any strategic points; a well-armed enemy with great mobility and modern rifles, who adopts guerilla tactics. The results in either case are, that the troops can march anywhere, and do anything, except catch the enemy; and that all their movements must be attended with loss.

If the question of subduing the tribes be regarded from a purely military standpoint, if time were no object, and there was no danger of a lengthy operation being interrupted by a change of policy at home, it would appear that the efforts of commanders should be, to induce the tribesmen to assume the offensive. On this point I must limit my remarks to the flat-bottomed valleys of Swat and Bajaur. To coerce a tribe like the Mamunds, a mixed brigade might camp at the entrance to the valley, and as at Inayat Kila, entrench itself very strongly. The squadron of cavalry could patrol the valley daily in complete security, as the tribesmen would not dare to leave the hills. All sowing of crops and agricultural work would be stopped. The natives would retaliate by firing into the camp at night. This would cause loss; but if every one were to dig a good hole to sleep in, and if the officers were made to have dinner before sundown, and forbidden to walk about except on duty after dark, there is no reason why the loss should be severe. At length the tribesmen, infuriated by the occupation of their valley, and perhaps rendered desperate by the approach of famine and winter, would make a tremendous attempt to storm the camp. With a strong entrenchment, a wire trip to break a rush, and modern rifles, they would be driven off with great slaughter, and once severely punished would probably beg for terms. If not, the process would be continued until they did so.

Such a military policy would cost about the same in money as the vigorous methods I have described, as though smaller numbers of troops might be employed, they would have to remain mobilised and in the field for a longer period. But the loss in personnel would be much less. As good an example of the success of this method as can be found, is provided by Sir Bindon Blood’s tactics at Nawagai, when, being too weak to attack the enemy himself, he encouraged them to attack him, and then beat them off with great loss.

From the point which we have now reached, it is possible, and perhaps not undesirable, to take a rapid yet sweeping glance of the larger military problems of the day. We have for some years adopted the “short service” system. It is a continental system. It has many disadvantages. Troops raised under it suffer from youth, want of training and lack of regimental associations. But on the Continent it has this one, paramount recommendation: it provides enormous numbers. The active army is merely a machine for manufacturing soldiers quickly, and passing them into the reserves, to be stored until they are wanted. European nations deal with soldiers only in masses. Great armies of men, not necessarily of a high standard of courage and training, but armed with deadly weapons, are directed against one another, under varying strategical conditions. Before they can rebound, thousands are slaughtered and a great battle has been won or lost. The average courage of the two nations may perhaps have been decided. The essence of the continental system is its gigantic scale.

We have adopted this system in all respects but one, and that the vital one. We have got the poor quality, without the great quantity. We have, by the short service system, increased our numbers a little, and decreased our standard a good deal. The reason that this system, which is so well adapted to continental requirements, confers no advantages upon us is obvious. Our army is recruited by a voluntary system. Short service and conscription are inseparable. For this reason, several stern soldiers advocate conscription. But many words will have to be spoken, many votes voted, and perhaps many blows struck before the British people would submit to such an abridgment of their liberties, or such a drag upon their commerce. It will be time to make such sacrifices when the English Channel runs dry.

Without conscription we cannot have great numbers. It should therefore be our endeavour to have those we possess of the best quality; and our situation and needs enforce this view. Our soldiers are not required to operate in great masses, but very often to fight hand to hand. Their campaigns are not fought in temperate climates and civilised countries. They are sent beyond the seas to Africa or the Indian frontier, and there, under a hot sun and in a pestilential land, they are engaged in individual combat with athletic savages. They are not old enough for the work.

Young as they are, their superior weapons and the prestige of the dominant race enable them to maintain their superiority over the native troops. But in the present war several incidents have occurred, unimportant, insignificant, it is true, but which, in the interests of Imperial expediency, are better forgotten. The native regiments are ten years older than the British regiments. Many of their men have seen service and have been under fire. Some of them have several medals. All, of course, are habituated to the natural conditions. It is evident how many advantages they enjoy. It is also apparent how very serious the consequences would be if they imagined they possessed any superiority. That such an assumption should even be possible is a menace to our very existence in India. Intrinsic merit is the only title of a dominant race to its possessions. If we fail in this it is not because our spirit is old and grown weak, but because our soldiers are young, and not yet grown strong.

Boys of twenty-one and twenty-two are expected to compete on equal terms with Sikhs and Gurkhas of thirty, fully developed and in the prime of life. It is an unfair test. That they should have held their own is a splendid tribute to the vigour of our race. The experiment is dangerous, and it is also expensive. We continue to make it because the idea is still cherished that British armies will one day again play a part in continental war. When the people of the United Kingdom are foolish enough to allow their little army to be ground to fragments between continental myriads, they will deserve all the misfortunes that will inevitably come upon them.

I am aware that these arguments are neither original nor new. I have merely arranged them. I am also aware that there are able, brilliant men who have spent their lives in the service of the State, who do not take the views I have quoted. The question has been regarded from an Indian point of view. There is probably no colonel in India, who commands a British regiment, who would not like to see his men five years older. It may be that the Indian opinion on the subject is based only on partial information, and warped by local circumstances. Still I have thought it right to submit it to the consideration of the public, at a time when the army has been filling such a prominent position, not only in the Jubilee procession and the frontier war, but also in the estimates presented to the House of Commons.

Passing from the concrete to the abstract, it may not be unfitting that these pages, which have recorded so many valiant deeds, should contain some brief inquiry into the nature of those motives which induce men to expose themselves to great hazards, and to remain in situations of danger. The circumstances of war contain every element that can shake the nerves. The whizzing of the projectiles; the shouts and yells of a numerous and savage enemy; the piteous aspect of the wounded, covered with blood and sometimes crying out in pain; the spurts of dust which on all sides show where Fate is stepping—these are the sights and sounds which assail soldiers, whose development and education enable them to fully appreciate their significance. And yet the courage of the soldier is the commonest of virtues. Thousands of men, drawn at random from the population, are found to control the instinct of self-preservation. Nor is this courage peculiar to any particular nation. Courage is not only common, but cosmopolitan. But such are the apparent contradictions of life, that this virtue, which so many seem to possess, all hold the highest. There is probably no man, however miserable, who would not writhe at being exposed a coward. Why should the common be precious? What is the explanation?

It appears to be this. The courage of the soldier is not really contempt for physical evils and indifference to danger. It is a more or less successful attempt to simulate these habits of mind. Most men aspire to be good actors in the play. There are a few who are so perfect that they do not seem to be actors at all. This is the ideal after which the rest are striving. It is one very rarely attained.

Three principal influences combine to assist men in their attempts: preparation, vanity and sentiment. The first includes all the force of discipline and training. The soldier has for years contemplated the possibility of being under fire. He has wondered vaguely what kind of an experience it would be. He has seen many who have gone through it and returned safely. His curiosity is excited. Presently comes the occasion. By road and railway he approaches daily nearer to the scene. His mind becomes familiar with the prospect. His comrades are in the same situation. Habit, behind which force of circumstances is concealed, makes him conform. At length the hour arrives. He observes the darting puffs of smoke in the distance. He listens to the sounds that are in the air. Perhaps he hears something strike with a thud and sees a soldier near him collapse like a shot pheasant. He realises that it may be his turn next. Fear grips him by the throat.

Then vanity, the vice which promotes so many virtues, asserts itself. He looks at his comrades and they at him. So far he has shown no sign of weakness. He thinks, they are thinking him brave. The dearly longed-for reputation glitters before his eyes. He executes the orders he receives.

But something else is needed to made a hero. Some other influence must help him through the harder trials and more severe ordeals which may befall him. It is sentiment which makes the difference in the end. Those who doubt should stroll to the camp fire one night and listen to the soldiers’ songs. Every one clings to something that he thinks is high and noble, or that raises him above the rest of the world in the hour of need. Perhaps he remembers that he is sprung from an ancient stock, and of a race that has always known how to die; or more probably it is something smaller and more intimate; the regiment, whatever it is called—”The Gordons,” “The Buffs,” “The Queen’s,”—and so nursing the name—only the unofficial name of an infantry battalion after all—he accomplishes great things and maintains the honour and the Empire of the British people.

It may be worth while, in the matter of names, to observe the advantages to a regiment of a monosyllabic appellation. Every one will remember Lieut.-Colonel Mathias’ speech to the Gordons. Imagine for a moment that speech addressed to some regiment saddled with a fantastic title on the territorial system, as, for instance, Mr. Kipling’s famous regiment, “The Princess Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen-Anspach’s Merthyr Tydvilshire Own Royal Loyal Light Infantry.” With the old numbers all started on equal terms.

This has been perhaps a cold-blooded chapter. We have considered men as targets; tribesmen, fighting for their homes and hills, have been regarded only as the objective of an attack; killed and wounded human beings, merely as the waste of war. We have even attempted to analyse the high and noble virtue of courage, in the hopes of learning how it may be manufactured.

The philosopher may observe with pity, and the philanthropist deplore with pain, that the attention of so many minds should be directed to the scientific destruction of the human species; but practical people in a business-like age will remember that they live in a world of men—not angels—and regulate their conduct accordingly.