Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, Vol. IV, by Charles Morris (published 1896)

From the main peak of the flag ship Victory hung out Admiral Nelson’s famous signal, “England expects every man to do his duty!”, an inspiring appeal, which has been the motto of English warriors since that day. The fleet under the command of the great admiral was drawing slowly in upon the powerful naval array of France, which lay awaiting him off the rocky shore of Cape Trafalgar. It was the morning of October 21, 1805, the dawn of the greatest day in the naval history of Great Britain.

Let us rapidly trace the events which led up to this scene,—the prologue to the drama about to be played. The year 1805 was one of threatening peril to England. Napoleon was then in the ambitious youth of his power, full of dreams of universal empire, his mind set on an invasion of the pestilent little island across the channel which should rival the “Invincible Armada” in power and far surpass it in performance.

Gigantic had been his preparations. Holland and Belgium were his, their coast-line added to that of France. In a hundred harbors all was activity, munitions being collected, and flat-bottomed boats built, in readiness to carry an invading army to England’s shores. The landing of William the Conqueror in 1066 was to be repeated in 1805. The land forces were encamped at Boulogne. Here the armament was to meet. Meanwhile, the allied fleets of France and Spain were to patrol the Channel, one part of them to keep Nelson at bay, the other part to escort the flotilla bearing the invading army.

While Napoleon was thus busy, his enemies were not idle. The war-ships of England hovered near the French ports, watching all movements, doing what damage they could. Lord Nelson keenly observed the hostile fleet. To throw him off the track, two French naval squadrons set sail for the West Indies, as if to attack the British islands there. Nelson followed. Suddenly turning, the decoying squadron came back under a press of sail, joined the Spanish fleet, and sailed for England. Nelson had not returned, but a strong fleet remained, under Sir Robert Calder, which was handled in such fashion as to drive the hostile ships back to the harbor of Cadiz.

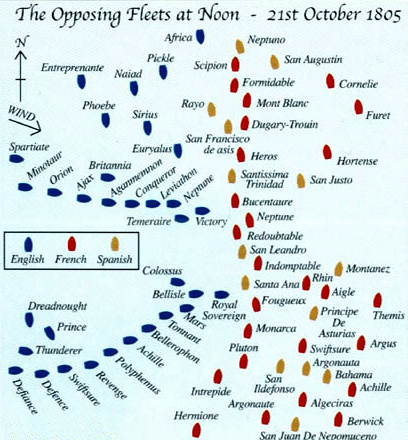

Such was the state of affairs when Nelson again reached England. Full of the spirit of battle, he hoisted his flag on the battle-ship Victory, and set sail in search of his foes. There were twenty-seven line-of-battle ships and four frigates under his command. The French fleet, under Admiral Villeneuve, numbered thirty-three sail of the line and seven frigates. Napoleon, dissatisfied with the disinclination of his fleet to meet that of England, and confident in its strength, issued positive orders, and Villeneuve sailed out of the harbor of Cadiz, and took position in two crescent-shaped lines off Cape Trafalgar. As soon as Nelson saw him he came on with the eagerness of a lion in sight of its prey, his fleet likewise in two lines, his signal flags fluttering with the inspiring order, “England expects every man to do his duty.”

The wind was from the west, blowing in light breezes; a long, heavy swell ruffled the sea. Down came the great ships, Collingwood, in the Royal Sovereign, commanding the lee-line; Nelson, in the Victory, leading the weather division. One order Nelson had given, which breathes the inflexible spirit of the man. “His admirals and captains, knowing his object to be that of a close and decisive action, would supply any deficiency of signals, and act accordingly. In case signals cannot be seen or clearly understood, no captain can do wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.”

Nelson wore that day his admiral’s frock-coat, bearing on the breast four stars, the emblems of the orders with which he had been invested. His officers beheld these ornaments with apprehension. There were riflemen on the French ships. He was offering himself as a mark for their aim. Yet none dare suggest that he should remove or cover the stars. “In honor I gained them, and in honor I will die with them,” he had said on a previous occasion.

The long swell set in to the bay of Cadiz. The English ships moved with it, all sail set, a light southwest wind filling their canvas. Before them lay the French ships, with the morning sun on their sails, presenting a stately and beautiful appearance.

On came the English fleet, like a flock of giant birds swooping low across the ocean. Like a white flock at rest awaited the French three-deckers. Collingwood’s line was the first to come into action, Nelson steering more to the north, that the flight of the enemy to Cadiz, in case of their defeat, should be prevented. Straight for the centre of the foeman’s line steered the Royal Sovereign, taking her station side by side with the Santa Anna, which she engaged at the muzzle of her guns.

“What would Nelson give to be here!” exclaimed Collingwood, in delight.

“See how that noble fellow, Collingwood, carries his ship into action!” responded Nelson from the deck of the Victory.

It was not long before the two fleets were in hot action, the British ships following Collingwood’s lead in coming to close quarters with the enemy. As the Victory approached, the French ships opened with broadsides upon her, in hopes of disabling her before she could close with them. Not a shot was returned, though men were falling on her decks until fifty lay dead or wounded, and her main-topmast, with all her studding-sails and booms, had been shot away.

“This is too warm work, Hardy, to last,” said Nelson, with a smile, as a splinter tore the buckle from the captain’s shoe.

Twelve o’clock came and passed. The Victory was now well in. Firing from both sides as she advanced, she ran in side by side with the Redoubtable, of the French fleet, both ships pouring broadsides into each other. On the opposite side of the Redoubtable came up the English ship Temeraire, while another ship of the enemy lay on the opposite side of the latter.

The four ships lay head to head and side to side, as close as if they had been moored together, the muzzles of their guns almost touching. So close were they that the middle- and lower-deck guns of the Victory had to be depressed and fired with light charges, lest their balls should pierce through the foe and injure the Temeraire. And lest the Redoubtable should take fire from the lower-deck guns, whose muzzles touched her side when they were rim out, the fireman of each gun stood ready with a bucket of water to dash into the hole made by the shot. While the starboard guns of the Victory were thus employed, her larboard guns were in full play upon the Bucentaure and the huge Santissima Trinidad. This warm work was repeated through the entire fleet. Never had been closer and hotter action.

The fight had reached its hottest when there came a tragical event that rendered the victory at Trafalgar, glorious as it was, a loss to England. The Redoubtable, after her first broadside, had closed her lower-deck ports, lest the English should board her through them. She did not fire another great gun during the action. But her tops, like those of her consorts, were filled with riflemen, whose balls swept the decks of the assailing ships. One of these, fired from the mizzen-top of the Redoubtable, not fifteen yards from where Nelson stood, struck him on the left shoulder, piercing the epaulette. It was about quarter after one, in the heat of the action. He fell upon his face.

“They have done for me, at last, Hardy,” he said, as his captain ran to his assistance.

“I hope not!” cried Hardy.

“Yes,” he replied, “my backbone is shot through.”

A thorough sailor to the last, he saw, as they were carrying him below, that the tiller ropes which had been shot away were not replaced, and ordered that this should be immediately attended to. Then, that he might not be seen by the crew, he spread his handkerchief over his face and his stars. But for his needless risk in revealing them before, he might have lived.

The cockpit was crowded with the wounded and dying men. Over their bodies he was carried, and laid upon a pallet in the midshipmen’s berth. The wound was mortal. A brief examination showed this. He had known it from the first, and said to the surgeon,—

“Leave me, and give your services to those for whom there is some hope. You can do nothing for me.”

Such was the fact. All that could be done was to fan him, and relieve his intense thirst with lemonade. On deck the fight continued with undiminished fury. The English star was in the ascendant. Ship after ship of the enemy struck, the cheers of the crew of the Victory heralding each surrender, while every cheer brought a smile of joy to the face of the dying veteran.

“Will no one bring Hardy to me?” he repeatedly cried. “He must be killed! He is surely dead!”

In truth, the captain dared not leave the deck. More than an hour elapsed before he was able to come down. He grasped in silence the hand of the dying admiral.

“Well, Hardy, how goes the day with us?” asked Nelson, eagerly.

“Very well,” was the answer. “Ten ships have struck; but five of the van have tacked, and show an intention to bear down upon the Victory. I have called two or three of our fresh ships around, and have no doubt of giving them a drubbing.”

“I hope none of our ships have struck,” said Nelson.

“There is no fear of that,” answered Hardy. Then came a moment’s silence, and then Nelson spoke of himself.

“I am a dead man, Hardy,” he said. “I am going fast; it will be all over with me soon. Come nearer to me. Let my dear Lady Hamilton have my hair and all other things belonging to me.”

“I hope it is not so bad as that,” said Hardy, with much emotion. “Dr. Beatty must yet hold out some hope of life.”

“Oh, no, that is impossible,” said Nelson. “My back is shot through: Beatty will tell you so.”

Captain Hardy grasped his hand again, the tears standing in his eyes, and then hurried on deck to hide the emotion he could scarcely repress.

Life slowly left the frame of the dying hero: every minute he was nearer death. Sensation vanished below his breast. He made the surgeon test and acknowledge this.

“You know I am gone,” he said. “I know it. I feel something rising in my breast which tells me so.”

“Is your pain great?” asked Beatty.

“So great, that I wish I were dead. Yet,” he continued, in lower tones, “one would like to live a little longer, too.”

A few moments of silence passed; then he said in the same low tone,—

“What would become of my poor Lady Hamilton if she knew my situation?”

Fifteen minutes elapsed before Captain Hardy returned. On doing so, he warmly grasped Nelson’s hand, and in tones of joy congratulated him on the victory which he had come to announce.

“How many of the enemy are taken, I cannot say,” he remarked; “the smoke hides them; but we have not less than fourteen or fifteen.”

“That’s well,” cried Nelson, “but I bargained for twenty. Anchor, Hardy, anchor!” he commanded, in a stronger voice.

“Will not Admiral Collingwood take charge of the fleet?” hinted Hardy.

“Not while I live, Hardy,” answered Nelson, with an effort to lift himself in his bed. “Do you anchor.”

Hardy started to obey this last order of his beloved commander. In a low tone Nelson called him back.

“Don’t throw me overboard, Hardy,” he pleaded. “Take me home that I may be buried by my parents, unless the king shall order otherwise. And take care of my dear Lady Hamilton, Hardy; take care of poor Lady Hamilton. Kiss me, Hardy.”

The weeping captain knelt and kissed him. “Now I am satisfied,” said the dying hero. “Thank God, I have done my duty.”

Hardy stood and looked down in sad silence upon him, then again knelt and kissed him on the forehead.

“Who is that?” asked Nelson.

“It is I, Hardy,” was the reply.

“God bless you, Hardy,” came in tones just above a whisper.

Hardy turned and left. He could bear no more. He had looked his last on his old commander.

“I wish I had not left the deck,” said Nelson; “for I see I shall soon be gone.”

It was true; life was fast ebbing.

“Doctor,” he said to the chaplain, “I have not been a great sinner.” He was silent a moment, and then continued, “Remember that I leave Lady Hamilton and my daughter Horatia as a legacy to my country.”

Words now came with difficulty.

“Thank God, I have done my duty,” he said, repeating these words again and again. They were his last words. He died at half-past four, three and a quarter hours after he had been wounded.

Meanwhile, Nelson’s prediction had been realized: twenty French ships had struck their flags. The victory of Trafalgar was complete; Napoleon’s hope of invading England was at an end. Nelson, dying, had saved his country by destroying the fleet of her foes. Never had a sun set in greater glory than did the life of this hero of the navy of Great Britain, the ruler of the waves.

5

Most excellent!