Editor’s note: Here follows the eleventh chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XI: THE ACTION OF THE MAMUND VALLEY, 16TH SEPTEMBER

The story has now reached a point which I cannot help regarding as its climax. The action of the Mamund Valley is recalled to me by so many vivid incidents and enduring memories, that it assumes an importance which is perhaps beyond its true historic proportions. Throughout the reader must make allowances for what I have called the personal perspective. Throughout he must remember, how small is the scale of operations. The panorama is not filled with masses of troops. He will not hear the thunder of a hundred guns. No cavalry brigades whirl by with flashing swords. No infantry divisions are applied at critical points. The looker-on will see only the hillside, and may, if he watches with care, distinguish a few brown clad men moving slowly about it, dwarfed almost to invisibility by the size of the landscape. I hope to take him close enough, to see what these men are doing and suffering; what their conduct is and what their fortunes are. But I would ask him to observe that, in what is written, I rigidly adhere to my role of a spectator. If by any phrase or sentence I am found to depart from this, I shall submit to whatever evil things the ingenuity of malice may suggest.

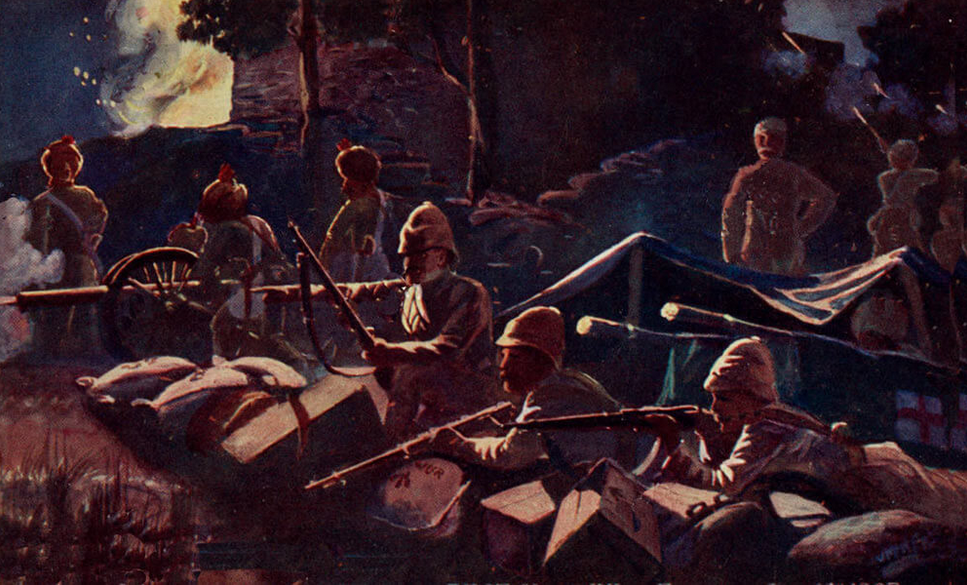

On the morning of the 16th, in pursuance of Sir Bindon Blood’s orders, Brigadier-General Jeffreys moved out of his entrenched camp at Inayat Kila, and entered the Mamund Valley. His intentions were, to chastise the tribesmen by burning and blowing up all defensible villages within reach of the troops. It was hoped, that this might be accomplished in a single day, and that the brigade, having asserted its strength, would be able to march on the 17th to Nawagai and take part in the attack on the Bedmanai Pass, which had been fixed for the 18th. Events proved this hope to be vain, but it must be remembered, that up to this time no serious opposition had been offered by the tribesmen to the columns, and that no news of any gathering had been reported to the general. The valley appeared deserted. The villages looked insignificant and defenceless. It was everywhere asserted that the enemy would not stand.

Reveille sounded at half-past five, and at six o’clock the brigade marched out. In order to deal with the whole valley at once, the force was divided into three columns, to which were assigned the following tasks:—

I. The right column, under Lieut.-Col. Vivian, consisting of the 38th Dogras and some sappers, was ordered to attack the village of Domodoloh.

II. The centre column, under Colonel Goldney, consisting of six companies Buffs, six companies 35th Sikhs, a half-company sappers, four guns of No.8 Mountain Battery and the squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers, was ordered to proceed to the head of the valley, and destroy the villages of Badelai and Shahi-Tangi (pronounced Shytungy).

III. The left column, under Major Campbell, consisting of five companies of the Guides Infantry, and some sappers, was directed against several villages at the western end of the valley.

Two guns and two companies from each battalion were left to protect the camp, and a third company of the Guides was detached to protect the survey party. This reduced the strength of the infantry in the field to twenty-three companies, or slightly over 1200 men. Deducting the 300 men of the 38th Dogras who were not engaged, the total force employed in the action was about 1000 men of all arms.

It will be convenient to deal with the fortunes of the right column first. Lieut.-Colonel Vivian, after a march of six miles, arrived before the village of Domodoloh at about 9 A.M. He found it strongly held by the enemy, whose aspect was so formidable, that he did not consider himself strong enough to attack without artillery and supports, and with prudence returned to camp, which he reached about 4 P.M. Two men were wounded by long-range fire.

The centre column advanced covered by Captain Cole’s squadron of Lancers, to which I attached myself. At about seven o’clock we observed the enemy on a conical hill on the northern slopes of the valley. Through the telescope, an instrument often far more useful to cavalry than field-glasses, it was possible to distinguish their figures. Long lines of men clad in blue or white, each with his weapon upright beside him, were squatting on the terraces. Information was immediately sent back to Colonel Goldney. The infantry, eager for action, hurried their march. The cavalry advanced to within 1000 yards of the hills. For some time the tribesmen sat and watched the gradual deployment of the troops, which was developing in the plain below them. Then, as the guns and infantry approached, they turned and began slowly to climb the face of the mountain.

In hopes of delaying them or inducing them to fight, the cavalry now trotted to within closer range, and dismounting, opened fire at 7.30 precisely. It was immediately returned. From high up the hillside, from the cornfields at the base, and from the towers of the villages, little puffs of smoke darted. The skirmish continued for an hour without much damage to either side, as the enemy were well covered by the broken ground and the soldiers by the gravestones and trees of a cemetery. Then the infantry began to arrive. The Buffs had been detached from Colonel Goldney’s column and were moving against the village of Badelai. The 35th Sikhs proceeded towards the long ridge, round the corner of which Shahi-Tangi stands. As they crossed our front slowly—and rather wearily, for they were fatigued by the rapid marching—the cavalry mounted and rode off in quest of more congenial work with the cavalryman’s weapon—the lance. I followed the fortunes of the Sikhs. Very little opposition was encountered. A few daring sharpshooters fired at the leading companies from the high corn. Others fired long-range shots from the mountains. Neither caused any loss. Colonel Goldney now ordered one and a half companies, under Captain Ryder, to clear the conical hill, and protect the right of the regiment from the fire—from the mountains. These men, about seventy-five in number, began climbing the steep slope; nor did I see them again till much later in the day. The remaining four and a half companies continued to advance. The line lay through high crops on terraces, rising one above the other. The troops toiled up these, clearing the enemy out of a few towers they tried to hold. Half a company was left with the dressing station near the cemetery, and two more were posted as supports at the bottom of the hills. The other two commenced the ascent of the long spur which leads to Shahi-Tangi.

It is impossible to realise without seeing, how very slowly troops move on hillsides. It was eleven o’clock before the village was reached. The enemy fell back “sniping,” and doing hardly any damage. Everybody condemned their pusillanimity in making off without a fight. Part of the village and some stacks of bhoosa, a kind of chopped straw, were set on fire, and the two companies prepared to return to camp.

But at about eight the cavalry patrols had reported the enemy in great strength at the northwest end of the valley. In consequence of this Brigadier-General Jeffreys ordered the Guides Infantry to join the main column. [Copy of message showing the time:—”To Officer, Commanding Guides Infantry.—Despatched 8.15 A.M. Received 8.57 A.M. Enemy collecting at Kanra; come up at once on Colonel Goldney’s left. C. Powell, Major, D.A.Q.M.G.”] Major Campbell at once collected his men, who were engaged in foraging, and hurried towards Colonel Goldney’s force. After a march of five miles, he came in contact with the enemy in strength on his left front, and firing at once became heavy. At the sound of the musketry the Buffs were recalled from the village of Badelai and also marched to support the 35th Sikhs.

While both these regiments were hurrying to the scene, the sound of loud firing first made us realise that our position at the head of the spur near Shahi-Tangi was one of increasing danger. The pressure on the left threatened the line of retreat, and no supports were available within a mile. A retirement was at once ordered. Up to this moment hardly any of the tribesmen had been seen. It appeared as if the retirement of the two companies was the signal for their attack. I am inclined to think, however, that this was part of the general advance of the enemy, and that even had no retirement been ordered the advanced companies would have been assailed. In any case the aspect of affairs immediately changed. From far up the hillsides men came running swiftly down, dropping from ledge to ledge, and dodging from rock to rock. The firing increased on every hand. Half a company was left to cover the withdrawal. The Sikhs made excellent practice on the advancing enemy, who approached by twos and threes, making little rushes from one patch of cover to another. At length a considerable number had accumulated behind some rocks about a hundred yards away. The firing now became heavy and the half-company, finding its flank threatened, fell back to the next position.

A digression is necessary to explain the peculiar configuration of the ground.

The spur, at the top of which the village stands, consists of three rocky knolls, each one higher than the other, as the main hill is approached. These are connected by open necks of ground, which are commanded by fire from both flanks. In section the ground resembles a switchback railway.

The first of these knolls was evacuated without loss, and the open space to the next quickly traversed. I think a couple of men fell here, and were safely carried away. The second knoll was commanded by the first, on to which the enemy climbed, and from which they began firing. Again the companies retired. Lieutenant Cassells remained behind with about eight men, to hold the knoll until the rest had crossed the open space. As soon as they were clear they shouted to him to retire. He gave the order.

Till this time the skirmishing of the morning might have afforded pleasure to the neuropath, experience to the soldier, “copy” to the journalist. Now suddenly black tragedy burst upon the scene, and all excitement died out amid a multitude of vivid trifles. As Lieutenant Cassells rose to leave the knoll, he turned sharply and fell on the ground. Two Sepoys immediately caught hold of him. One fell shot through the leg. A soldier who had continued firing sprang into the air, and, falling, began to bleed with strange and terrible rapidity from his mouth and chest. Another turned on his back kicking and twisting. A fourth lay quite still. Thus in the time it takes to write half the little party were killed or wounded. The enemy had worked round both flanks and had also the command. Their fire was accurate.

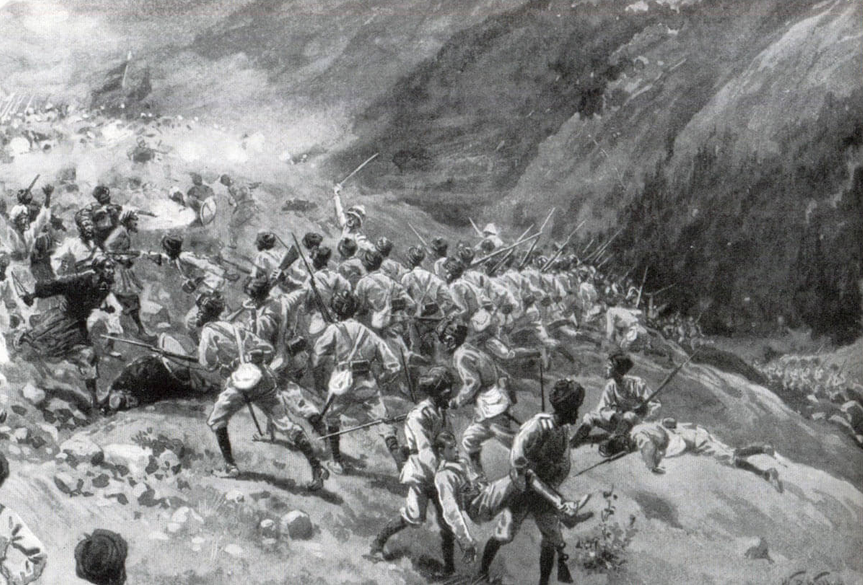

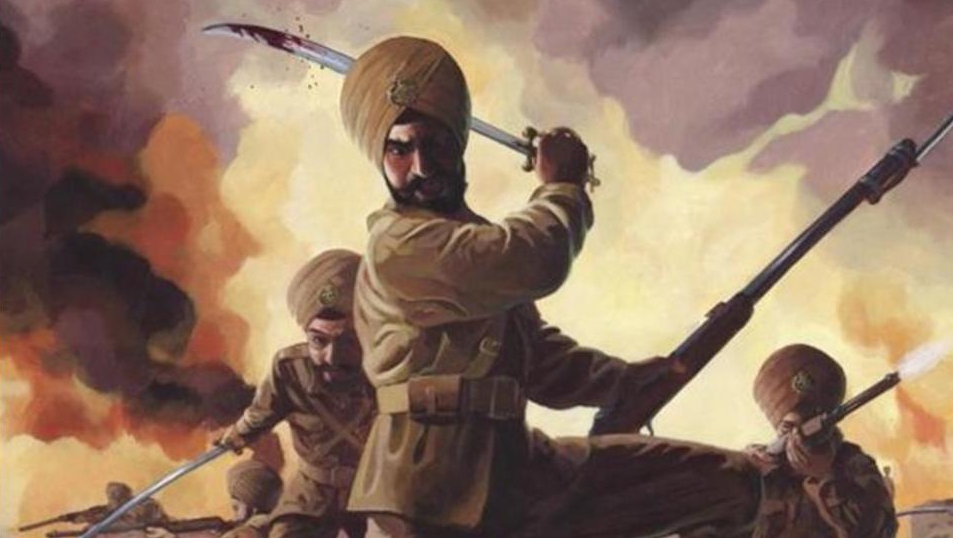

Two officers, the subadar major, by name Mangol Singh, and three or four Sepoys ran forward from the second knoll, to help in carrying the wounded off. Before they reached the spot, two more men were hit. The subadar major seized Lieutenant Cassells, who was covered with blood and unable to stand, but anxious to remain in the firing line. The others caught hold of the injured and began dragging them roughly over the sharp rocks in spite of their screams and groans. Before we had gone thirty yards from the knoll, the enemy rushed on to it, and began firing. Lieutenant Hughes, the adjutant of the regiment, and one of the most popular officers on the frontier, was killed. The bullets passed in the air with a curious sucking noise, like that produced by drawing the air between the lips. Several men also fell. Lieut.-Colonel Bradshaw ordered two Sepoys to carry the officer’s body away. This they began to do. Suddenly a scattered crowd of tribesmen rushed over the crest of the hill and charged sword in hand, hurling great stones. It became impossible to remain an impassive spectator. Several of the wounded were dropped. The subadar major stuck to Lieutenant Cassells, and it is to him the lieutenant owes his life. The men carrying the other officer, dropped him and fled. The body sprawled upon the ground. A tall man in dirty white linen pounced down upon it with a curved sword. It was a horrible sight.

Had the swordsmen charged home, they would have cut everybody down. But they did not. These wild men of the mountains were afraid of closing. The retirement continued. Five or six times the two companies, now concentrated, endeavoured to stand. Each time the tribesmen pressed round both flanks. They had the whole advantage of ground, and commanded, as well as out-flanked the Sikhs. At length the bottom of the spur was reached, and the remainder of the two companies turned to bay in the nullah with fixed bayonets. The tribesmen came on impetuously, but stopped thirty yards away, howling, firing and waving their swords.

No other troops were in sight, except our cavalry, who could be seen retiring in loose squadron column—probably after their charge. They could give no assistance. The Buffs were nearly a mile away. Things looked grave. Colonel Goldney himself tried to re-form the men. The Sikhs, who now numbered perhaps sixty, were hard pressed, and fired without effect. Then some one—who it was is uncertain—ordered the bugler to sound the “charge.” The shrill notes rang out not once but a dozen times. Every one began to shout. The officers waved their swords frantically. Then the Sikhs commenced to move slowly forward towards the enemy, cheering. It was a supreme moment. The tribesmen turned, and began to retreat. Instantly the soldiers opened a steady fire, shooting down their late persecutors with savage energy.

Then for the first time, I perceived that the repulse was general along the whole front. What I have described was only an incident. But the reader may learn from the account the explanation of many of our losses in the frontier war. The troops, brave and well-armed, but encumbered with wounded, exhausted by climbing and overpowered by superior force, had been ordered to retire. This is an operation too difficult for a weak force to accomplish. Unless supports are at hand, they must be punished severely, and the small covering parties, who remain to check the enemy, will very often be cut to pieces, or shot down. Afterwards in the Mamund Valley whole battalions were employed to do what these two Sikh companies had attempted. But Sikhs need no one to bear witness to their courage.

During the retirement down the spur, I was unable to observe the general aspect of the action, and now in describing it, I have dealt only with the misadventures of one insignificant unit. It is due to the personal perspective. While the two advanced companies were being driven down the hill, a general attack was made along the whole left front of the brigade, by at least 2000 tribesmen, most of whom were armed with rifles. To resist this attack there were the cavalry, the two supporting companies of the 35th Sikhs and five of the Guides Infantry, who were arriving. All became engaged. Displaying their standards, the enemy advanced with great courage in the face of a heavy fire. Many were killed and wounded, but they continued to advance, in a long skirmish line, on the troops. One company of the 35th became seriously involved. Seeing this, Captain Cole moved his squadron forward, and though the ground was broken, charged. The enemy took refuge in the nullah, tumbling into it standards and all, and opened a sharp fire on the cavalry at close range, hitting several horses and men. The squadron fell back. But the moral effect of their advance had been tremendous. The whole attack came to a standstill. The infantry fire continued. Then the tribesmen began to retire, and they were finally repulsed at about twelve o’clock.

An opportunity was now presented of breaking off the action. The brigade had started from camp divided, and in expectation that no serious resistance would be offered. It had advanced incautiously. The leading troops had been roughly handled. The enemy had delivered a vigorous counter attack. That attack had been repulsed with slaughter, and the brigade was concentrated. Considering the fatigues to which the infantry had been exposed, it would perhaps have been more prudent to return to camp and begin again next morning. But Brigadier-General Jeffries was determined to complete the destruction of Shahi-Tangi, and to recover the body of Lieutenant Hughes, which remained in the hands of the enemy. It was a bold course. But it was approved by every officer in the force.

A second attack was ordered. The Guides were to hold the enemy in check on the left. The Buffs, supported by the 35th Sikhs, were to take the village. Orders were signalled back to camp for all the available troops to reinforce the column in the field, and six fresh companies consequently started. At one o’clock the advance recommenced, the guns came into action on a ridge on the right of the brigade, and shelled the village continuously.

Again the enemy fell back “sniping,” and very few of them were to be seen. But to climb the hill alone took two hours. The village was occupied at three o’clock, and completely destroyed by the Buffs. At 3.30 orders reached them to return to camp, and the second withdrawal began. Again the enemy pressed with vigour, but this time there were ten companies on the spur instead of two, and the Buffs, who became rear-guard, held everything at a distance with their Lee-Metford rifles. At a quarter to five the troops were clear of the hills and we looked about us.

While this second attack was being carried out, the afternoon had slipped away. At about two o’clock Major Campbell and Captain Cole, both officers of great experience on the frontier, had realised the fact, that the debate with the tribesmen could not be carried to a conclusion that day. At their suggestion a message was heliographed up to the General’s staff officer on the spur near the guns, as follows: “It is now 2.30. Remember we shall have to fight our way home.” But the brigadier had already foreseen this possibility, and had, as described, issued orders for the return march. These orders did not reach Captain Ryder’s company on the extreme right until they had become hard pressed by the increasing attack of the enemy. Their wounded delayed their retirement. They had pushed far up the mountain side, apparently with the idea they were to crown the heights, and we now saw them two miles away on the sky line hotly engaged.

While I was taking advantage of a temporary halt, to feed and water my pony, Lieutenant MacNaghten of the 16th Lancers pointed them out to me, and we watched them through our glasses. It was a strange sight. Little figures running about confusedly, tiny puffs of smoke, a miniature officer silhouetted against the sky waving his sword. It seemed impossible to believe that they were fighting for their lives, or indeed in any danger. It all looked so small and unreal. They were, however, hard pressed, and had signalled that they were running out of cartridges. It was then five o’clock, and the approach of darkness was accelerated by the heavy thunderclouds which were gathering over the northern mountains.

At about 3.30 the brigadier had ordered the Guides to proceed to Ryder’s assistance and endeavour to extricate his company. He directed Major Campbell to use his own discretion. It was a difficult problem, but the Guides and their leader were equal to it. They had begun the day on the extreme left. They had hurried to the centre. Now they were ordered to the extreme right. They had already marched sixteen miles, but they were still fresh. We watched them defiling across the front, with admiration. Meanwhile, the retirement of the brigade was delayed. It was necessary that all units should support each other, and the troops had to wait till the Guides had succeeded in extricating Ryder. The enemy now came on in great strength from the north-western end of the valley, which had been swarming with them all day, so that for the first time the action presented a fine spectacle.

Across the broad plain the whole of the brigade was in echelon. On the extreme right Ryder’s company and the Guides Infantry were both severely engaged. Half a mile away to the left rear the battery, the sappers and two companies of the 35th Sikhs were slowly retiring. Still farther to the left were the remainder of the 35th, and, at an interval of half a mile, the Buffs. The cavalry protected the extreme left flank. This long line of troops, who were visible to each other but divided by the deep broad nullahs which intersected the whole plain, fell back slowly, halting frequently to keep touch. Seven hundred yards away were the enemy, coming on in a great half-moon nearly three miles long and firing continually. Their fire was effective, and among other casualties at this time Lieutenant Crawford, R.A., was killed. Their figures showed in rows of little white dots. The darkness fell swiftly. The smoke puffs became fire flashes. Great black clouds overspread the valley and thunder began to roll. The daylight died away. The picture became obscured, and presently it was pitch dark. All communication, all mutual support, all general control now ceased. Each body of troops closed up and made the best of their way to the camp, which was about seven miles off. A severe thunderstorm broke overhead. The vivid lightning displayed the marching columns and enabled the enemy to aim. Individual tribesmen ran up, shouting insults, to within fifty yards of the Buffs and discharged their rifles. They were answered with such taunts as the limited Pushtu of the British soldier allows and careful volleys. The troops displayed the greatest steadiness. The men were determined, the officers cheery, the shooting accurate. At half-past eight the enemy ceased to worry us. We thought we had driven them off, but they had found a better quarry.

The last two miles to camp were painful. After the cessation of the firing the fatigue of the soldiers asserted itself. The Buffs had been marching and fighting continuously for thirteen hours. They had had no food, except their early morning biscuit, since the preceding night. The older and more seasoned amongst them laughed at their troubles, declaring they would have breakfast, dinner and tea together when they got home. The younger ones collapsed in all directions.

The officers carried their rifles. Such ponies and mules as were available were laden with exhausted soldiers. Nor was this all. Other troops had passed before us, and more than a dozen Sepoys of different regiments were lying senseless by the roadside. All these were eventually carried in by the rear-guard, and the Buffs reached camp at nine o’clock.

Meanwhile, the Guides had performed a brilliant feat of arms, and had rescued the remnants of the isolated company from the clutches of the enemy. After a hurried march they arrived at the foot of the hill down which Ryder’s men were retiring. The Sikhs, utterly exhausted by the exertions of the day, were in disorder, and in many cases unable from extreme fatigue even to use their weapons. The tribesmen hung in a crowd on the flanks and rear of the struggling company, firing incessantly and even dashing in and cutting down individual soldiers. Both officers were wounded. Lieutenant Gunning staggered down the hill unaided, struck in three places by bullets and with two deep sword cuts besides. Weary, outnumbered, surrounded on three sides, without unwounded officers or cartridges, the end was only a matter of moments. All must have been cut to pieces. But help was now at hand.

The Guides formed line, fixed bayonets and advanced at the double towards the hill. At a short distance from its foot they halted and opened a terrible and crushing fire upon the exulting enemy. The loud detonations of their company volleys were heard and the smoke seen all over the field, and on the left we wondered what was happening. The tribesmen, sharply checked, wavered. The company continued its retreat. Many brave deeds were done as the night closed in. Havildar Ali Gul, of the Afridi Company of the Guides, seized a canvas cartridge carrier, a sort of loose jacket with large pockets, filled it with ammunition from his men’s pouches, and rushing across the fire-swept space, which separated the regiment from the Sikhs, distributed the precious packets to the struggling men. Returning he carried a wounded native officer on his back. Seeing this several Afridis in the Guides ran forward, shouting and cheering, to the rescue, and other wounded Sikhs were saved by their gallantry from a fearful fate. At last Ryder’s company reached the bottom of the hill and the survivors re-formed under cover of the Guides.

These, thrown on their own resources, separated from the rest of the brigade by darkness and distance and assailed on three sides by the enemy, calmly proceeded to fight their way back to camp. Though encumbered with many wounded and amid broken ground, they repulsed every attack, and bore down all the efforts which the tribesmen made to intercept their line of retreat. They reached camp at 9.30 in safety, and not without honour. The skill and experience of their officers, the endurance and spirit of the men, had enabled them to accomplish a task which many had believed impossible, and their conduct in the action of the Mamund Valley fills a brilliant page in the history of the finest and most famous frontier regiment. [The gallantry of the two officers, Captain Hodson and Lieut. Codrington, who commanded the two most exposed companies, was the subject of a special mention in despatches, and the whole regiment were afterwards complimented by Brigadier-General Jeffreys on their fine performance.]

As the Buffs reached the camp the rain which had hitherto held off came down. It poured. The darkness was intense. The camp became a sea of mud. In expectation that the enemy would attack it, General Jeffreys had signalled in an order to reduce the perimeter. The camp was therefore closed up to half its original size.

Most of the tents had been struck and lay with the baggage piled in confused heaps on the ground. Many of the transport animals were loose and wandering about the crowded space. Dinner or shelter there was none. The soldiers, thoroughly exhausted, lay down supperless in the slush. The condition of the wounded was particularly painful. Among the tents which had been struck were several of the field hospitals. In the darkness and rain it was impossible to do more for the poor fellows than to improve the preliminary dressings and give morphia injections, nor was it till four o’clock on the next afternoon that the last were taken out of the doolies.

After about an hour the rain stopped, and while the officers were bustling about making their men get some food before they went to sleep, it was realised that all the troops were not in camp. The general, the battery, the sappers and four companies of infantry were still in the valley. Presently we heard the firing of guns. They were being attacked,—overwhelmed perhaps. To send them assistance was to risk more troops being cut off. The Buffs who were dead beat, the Sikhs who had suffered most severe losses, and the Guides who had been marching and fighting all day, were not to be thought of. The 38th Dogras were, however, tolerably fresh, and Colonel Goldney, who commanded in the absence of the General, at once ordered four companies to parade and march to the relief. Captain Cole volunteered to accompany them with a dozen sowars. The horses were saddled. But the order was countermanded, and no troops left the camp that night.

Whether this decision was justified or not the reader shall decide. In the darkness and the broken ground it was probable the relief would never have found the general. It was possible that getting involved among the nullahs they would have been destroyed. The defenders of the camp itself were none too many. The numbers of the enemy were unknown. These were weighty reasons. On the other hand it seemed unsoldierly to lie down to sleep while at intervals the booming of the guns reminded us, that comrades were fighting for their lives a few miles away in the valley.