Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Famous Discoverers and Explorers of America, by Charles H. L. Johnston (published 1917). All spelling in the original.

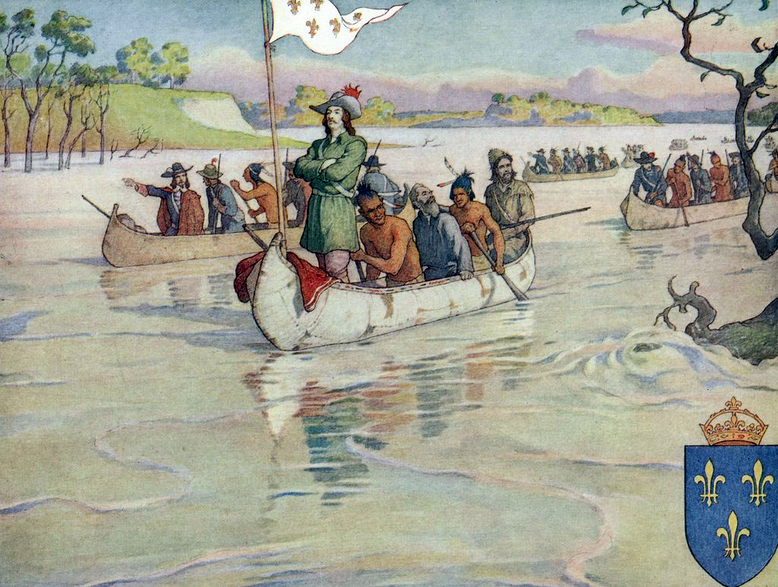

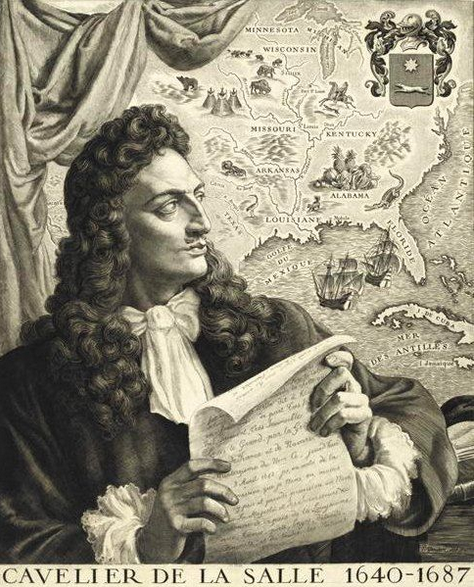

While good Father Marquette was gliding over the muddied waters of the Mississippi, gazing at wonderful sights which no Frenchman had dreamed of heretofore, a man lived upon the banks of the St. Lawrence who brooded over projects of peril and adventure and gazed wistfully towards the Far West. This was no other than Robert, Chevalier de La Salle, a Frenchman who had come to Canada about the year 1667. He had been born at Rouen, in Normandy, of a noble family, and had been well educated in a Jesuit seminary.

Urged onward by a desire for both adventure and money, this vigorous young blade emigrated to Canada. Here he traveled up and down the great river St. Lawrence from Tadoussac to Sault Ste. Marie, and busied himself in trading European merchandise for beaver, bear, and other skins. He built houses for the storage of furs and merchandise, made excursions among the Indian tribes bordering on the shore of Lake Ontario, and penetrated as far as the Huron country in the north, where he lived for some time among the redskins, learning their life, their manners, and their language.

Perhaps some of you have taken the steamer at Toronto, have threaded your way among the beautiful Thousand Isles, and have shot through the foaming spray of the Lachine rapids, before reaching the city of Montreal. This seething cataract was named by the adventurous La Salle, for he hoped to find the St. Lawrence leading into the China Sea, and, to commemorate this anticipation, called the trading station, upon the Island of Montreal—La Chine (or the China) a name which has fastened itself to the rapids, and a name which it has borne to the present day.

Here the adventurous Frenchman was resting when word was brought to him of the expedition of Marquette and Joliet. He felt certain that the Mississippi discharged itself into the great Gulf of Mexico, a fact which inflamed his desire to complete the discovery of that mighty watercourse. He wished to found colonies upon its banks and to open up new avenues of trade between France and the vast countries of the West. Nor did he lose his visions of China and Japan. From the head-waters of the Mississippi, he still hoped to find a passage to those distant countries, and thus, stirred with ideas of conquest and glory for his beloved France, he made a voyage to his native shores towards the end of the year 1677, hoping to gain assistance from the King for his ambitious designs.

The French monarch gave a ready ear to the talk of the venturesome Canadian. He was authorized to push his discoveries as far as he chose to the westward, and to build forts wherever he should think proper. In order to meet the large expense of his labors he was given the exclusive traffic in buffalo skins. Yet he was also forbidden to trade with the Hurons and other Indians, who usually brought furs to Montreal, for fear that he would interfere with the established traders and incur their jealousy and displeasure.

La Salle had the true love of adventure, a passion for exploring unknown lands, and an ambition to build up a great name for himself which should rival that of the early discoverers and conquerors of the New World. He wished, in fact, to die great. Let us see how he succeeded!

Two months after receiving this patent, the adventurer sailed from the shores of France, accompanied by the Chevalier Tonty, the Sieur de La Motte, and a pilot, ship-carpenters, mariners and other persons, about thirty in all. He had also a quantity of arms and ammunition, with a store of anchors, cordage, and other materials necessary for rigging the small vessels which he had determined to construct for the navigation of the lakes.

He arrived at Quebec near the end of September; but here he remained no longer than was necessary to arrange his affairs, for he hastened forward, passed up the dangerous rapids of the St. Lawrence in canoes, and at length reached Fort Frontenac, which he had erected at the eastern extremity of Lake Ontario, where the St. Lawrence issues from that great, blue inland sea.

La Salle was eager for exploration. Busily he prepared to build and equip a vessel above the Falls of Niagara, so that he could navigate the upper lakes. His men worked hard and had, before long, fitted out a brigantine of ten tons in which they stowed away everything needed for the construction of a second vessel. This barque had been made at Fort Frontenac, the year before, with two others, which were used for bringing supplies. It was a small boat, but was suitable for the purpose.

In order to have any success in building a fort and a ship on the waters of the Niagara River, it was necessary to have the good will of the red men who lived in the surrounding country. The Senecas here had their hunting grounds, and they were a powerful tribe, excellent in the hunting field, bloodthirsty on the field of war. So La Motte had orders from La Salle to go on an embassy to this nation, to hold a council with the chiefs, explain his object, and gain their consent.

With some well-armed men, La Motte consequently traveled about thirty miles through the woods, and came, at length, to the great village of these redskins. Before a roaring council fire, around which the Indians gathered with their usual grave and serious countenances, both white men and red delivered many speeches. The French promised to establish a blacksmith at Niagara, who should repair the guns of the red men, and, as a result of this guarantee, the Senecas gave them permission to establish a trading place and fort in the wilderness. Well satisfied with the mission, La Motte and his companions went back to Niagara.

La Salle soon arrived, sailing thither from Fort Frontenac in one of his small vessels, laden with provisions, with merchandise, and materials for rigging the new ship: the first to glide over the waves of these great western lakes. In person he visited the Seneca Indians, and, by soft speech and flattering words, secured their friendship and good-will.

Yet he had enemies, too, for the monopoly which he had gained from the government and the large scale upon which he conducted his affairs, raised, against him, a host of traducers among the traders and merchants of Canada. In order to thwart his designs, they told the Indians that his plans of building forts and ships on the border was in order to curb their power. Agents were sent among the redskins in order to sow the seeds of hostility to this ambitious Frenchman.

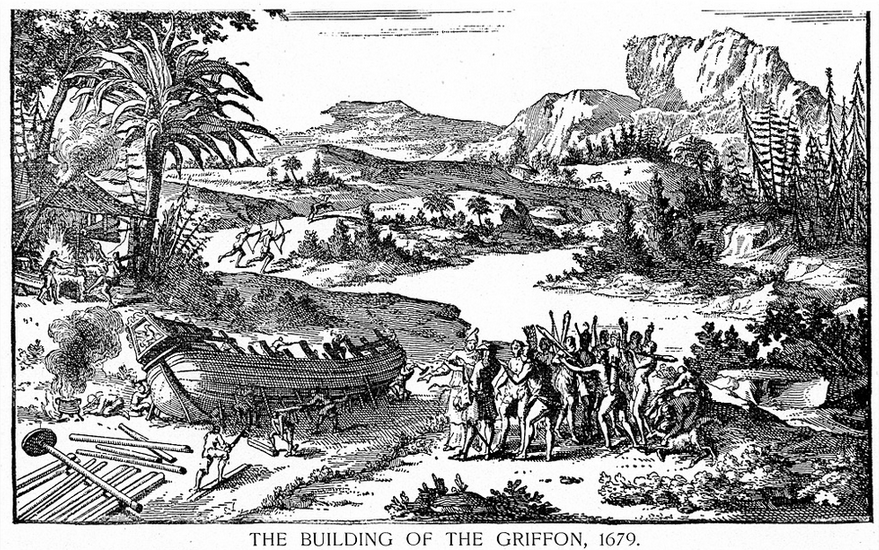

These moves against him were well known to La Salle, yet it did not put an end to his plans. About two miles above the Falls of Niagara, he selected a place for a dock-yard at the outlet of a creek, on the western side of the Niagara River. Here the keel of the new vessel was laid, and, in a very short time, her form began to appear. An Indian woman brought word that a plot had been hatched to burn the vessel, while it was on the stocks, yet the redskins did not molest it, and soon she proudly glided into the water. She was called the Griffin, in honor of the Count de Frontenac, who had two griffins upon his coat of arms.

It was the month of August, a time of softness and mellow sunlight in the Canadian wilderness, when, bathed in a flood of radiance, the sails of the Griffin were spread to the winds of Lake Erie. Heretofore, only birch-bark canoes had floated upon the surface of this wind-tossed sheet of water, now a real vessel was plowing a westward course over the rocking billows. The voyage was a prosperous one, and, on the 27th day of August, the little company of explorers, thirty-four in all, reached the Island of Mackinac, where the redskinned denizens of the forest looked with wonder and amazement upon this ship, the first which they had ever seen, calling her the great wooden canoe.

The Sieur de La Salle dressed himself in a scarlet cloak, in order to make an impression upon the redskins, and, attended by some of his soldiers, made a visit of ceremony to the head men of the village. Here his missionaries celebrated mass, and here he was received and entertained with much civility by the red men. Yet, although the redskins showed him much courtesy on the surface, their minds had been poisoned by the lies which had been circulated among them by his enemies, and for the same reason several of his followers had deserted. Not deterred by this happening, La Salle again entered his ship, hoisted sail, and soon was coasting along the northern borders of Lake Michigan.

After a voyage of about a hundred miles the Griffin reached Green Bay, where anchor was cast before a small island at its mouth. This island was inhabited by Pottawattomies, and here La Salle found several Frenchmen, who had preceded him in birch canoes, had gathered a supply of stores, and had also collected a vast quantity of furs. With these he loaded his vessel; sent it back to Niagara, for the purpose of satisfying his creditors; and ordered his navigators to return as soon as possible, and to pursue their voyage to the mouth of the Miami River at the south-eastern extremity of Lake Michigan.

The adventurers now remaining consisting of fourteen persons, who were soon paddling down the west shore of Lake Michigan in four bark canoes, laden with carpenters’ tools, a blacksmith’s forge, merchandise, and arms. After a stormy passage, they reached the mouth of the Miami River, since called the St. Joseph. Winter was approaching, hostile natives were near, so La Salle determined to build a fort. A hill was selected as the proper position for the stockade, the bushes were chopped down and logs were cut and hewn, so that a breastwork could be constructed, inclosing a space about eighty feet long, by forty broad. It was surrounded by palisades and was called Fort Miami.

All hands were thus kept busy during the month of November. In spite of this occupation, the men were very discontented, for they had no other food but the flesh of bears, which some Indian hunters killed in the woods. The Frenchmen did not like this, and wished to go into the woods in order to hunt deer and other game. This permission was refused by La Salle, as he saw that they were more bent upon desertion than upon assisting in improving the larder.

As they thus grumbled and worked at the edge of the wilderness, the Chevalier de Tonty came down the lake with two canoes well stocked with deer which he had recently killed. Hurrah! Here was a different kind of meat, at last, and this cheered the spirits of all the company. Yet there was bad news, also, for the good Chevalier brought word of the total loss of the ship which had brought them hither. No sight had ever been had of her, and, although the red men, who lived along the shores of Lake Michigan were closely questioned, no one brought any word of the ill-fated Griffin, which doubtless had been swallowed up by the waves of Lake Michigan, while on her way from the island of Mackinac. La Salle was much distressed, yet he had become accustomed to the buffeting of ill fortune in the wilderness, and, consequently turned again towards the wilderness with renewed courage and resolution to go onward, to explore, and to bring back news of these virgin forests and this interesting country.

An Indian hunter, who had been sent out to look for deer, came and told them where there was a portage to the head-waters of the Kankakee River. So, desirous of moving onward, they followed him down stream and paddled for a hundred miles on the muddy waters, which wound through marshes and a dense growth of tall rushes and alder bushes. The adventurers became much in need of provisions, for at this season the buffalo had traveled south; yet, they succeeded in killing two deer, several wild turkeys, and a few swans. Providence also came to their relief, for a stray buffalo was found sticking fast in a marsh, and it was therefore captured with ease.

At length the canoes floated upon the waters of the Illinois River, and, as they paddled onward, the voyagers came upon an Indian village where were great quantities of corn. The inhabitants had departed upon a hunt, so the ravenous Frenchmen appropriated a large store of grain for their own use. They kept on their way, reached a great lake, called Lake Peoria, and found a second Indian village upon the bank, the inhabitants of which met them with great friendliness and good will.

Here La Salle decided to build a fort. It was named Fort Crèvecœur, or the Broken Heart, so called because of the sadness which he had experienced at the loss of the good ship Griffin. The men also constructed a brigantine, forty-two feet long and twelve feet broad, in which it was hoped to make further discoveries in the Mississippi. When it had been completed, a priest, called Father Hennepin, was sent down the Illinois River to make further explorations, not in this boat, but in a canoe, accompanied by two Frenchmen and an Indian; while La Salle, himself, determined to begin an overland journey to Fort Frontenac, assisted by three Frenchmen and an Indian hunter. The Chevalier de Tonty was left in command of the fort, with sixteen men and two missionaries.

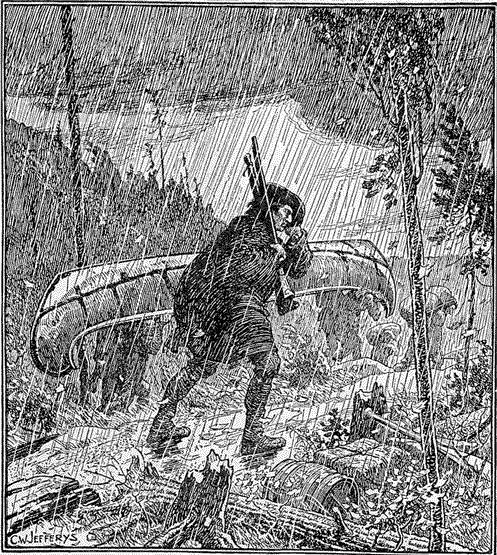

La Salle had quite an undertaking before him, but he did not quail. He was to travel over land, and on foot, through vast forests and through bogs and morasses, to Fort Frontenac, a distance of twelve hundred miles. He had to journey along the southern shores of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, ford numerous rivers and cross others on rafts, all of this in a season when snow hid the ground and floating ice rendered traveling most fatiguing. Nothing seemed impossible to his strong heart and unbending resolution. Shouldering his knapsack and musket, he bade adieu to his companions of the wilderness, and set his face towards far distant Canada.

No record has been preserved of the incidents of his long and perilous journey from the slow-moving Illinois to the blue and sparkling St. Lawrence. At any rate, he arrived without mishap at Fort Frontenac, where he was chagrined and mortified to find his affairs in a condition of confusion that was deplorable. His heaviest loss, of course, was that of the Griffin, with her cargo valued at twelve thousand dollars; but, besides this mishap, he found that his agents had despoiled him of all the profits of his trade. Some of his employees, in fact, had stolen his goods and had run away with them to the Dutch of New York. A rumor had been circulated to the effect that he and his whole party had been drowned on their voyage up the lakes, so his creditors had seized upon his effects, and had wasted them by forced sales. All Canada seemed to have conspired against him. Many a less resolute heart than his own would have failed, but despair was never known to settle upon the mind of the Chevalier La Salle. He was the first Theodore Roosevelt of the United States.

The adventurer had still one friend left,—Count Frontenac, whose influence and authority was now exerted in his favor. They discussed together the Mississippi problem and determined to give up the plan of navigating this mighty water-course in a ship. Instead, La Salle decided to prosecute his explorations with canoes.

He engaged more men, left Fort Frontenac on the 23d day of July, 1680, and, although detained by head winds on Lake Ontario, reached Mackinac during the month of September. By offering brandy in exchange for Indian corn, he soon had enough to satisfy his needs, and, embarking on the rough waters of Lake Michigan, at length arrived at the mouth of the river Miami. The fort which he had left there had been plundered and dismantled!

Journeying south, La Salle reached the villages of the Illinois, which he found had been sacked and burned by the Iroquois during his absence. He saw nothing of Tonty and those Frenchmen whom he had left behind him, a proof that they had either been killed or dispersed. So he returned to the Miami River and here spent the winter, visiting the Indian tribes near Lake Michigan. Here he learned that the Iroquois had attacked the settlements of the Illinois with vindictive ferocity, during his absence, driving the red men far westward across the Mississippi. As for the Frenchmen, whom he had left behind him, no one seemed to know what had become of them.

Towards the end of May, 1681, the vigorous explorer left the Miami River, and, after a prosperous voyage, once more entered the harbor of Mackinac. What was his joy to here find the Chevalier Tonty and those Frenchmen, whom he had last seen in the wilderness. They had passed through great dangers, but had at length escaped from the bloodthirsty Iroquois and had reached the French fortress, lean, haggard, but praising God that they had escaped with their lives. La Salle embraced them all, gave them presents of firearms and blankets, and begged them to accompany him again into the wilderness.

The Chevalier was now determined to journey down the entire length of the Mississippi, and, with this end in view, took into his service a company of Frenchmen, together with a number of eastern Indians, Abenakis, and Loups, or Mahingans, as they were called by the French writers. Putting Fort Frontenac in command of the Sieur de La Forest, he journeyed by canoe to Niagara, where a stockade had recently been built, called Fort de Tonty, and thence embarked with his entire company in canoes for the Miami River, which he reached in safety. Six weeks were now spent in making arrangements for the great trip down the river.

There were twenty-three Frenchmen in the party, eighteen savages, ten Indian women, and three children. The redskins insisted on taking these women with them to prepare their food, according to their custom, while they were fishing and hunting. When all was ready the adventurers started for the mouth of the Chicago River, which was found to be frozen.