Editor’s Note: The following comprises the nineteenth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XIX

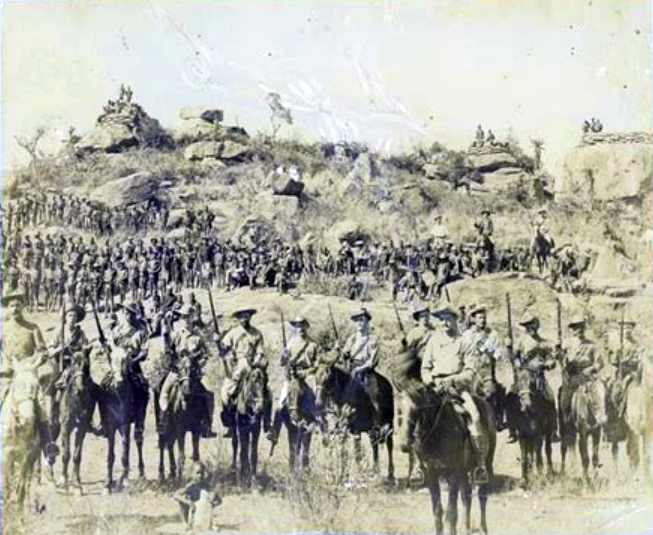

On the way back to Bulawayo we were met by Colonel Napier and Captain Nicholson, and it was arranged that as strong a force as could be spared from the town should be sent out again to the Umguza on the morrow, under the command of the former gentleman. Accordingly, at about eleven o’clock on Monday, 20th April, a force of two hundred and thirty white men and one hundred colonial natives, all told, left Bulawayo for the scene of the previous day’s skirmish. With the force were a seven-pounder, a Hotchkiss, and a Maxim. Captain Macfarlane had command of the right flank, and Captain Van Niekerk of the left; whilst I was in charge of a detachment of men on foot, drawn from various corps, and a body of Colenbrander’s natives were under the command of Captain Cardigan.

This was a most disappointing day for all those who wanted a little excitement, as the Matabele and the officers commanding our column were at cross purposes; the former wanting the white men to cross the river and fight them in the bush, and the latter being in favour of the Kafirs coming through to their side, and attacking a position defended with artillery. The result was that there was no fight.

The decision not to cross the Umguza may have been a wise one, but it was not popular with the men, who marched back to town in a very dejected frame of mind; so strong was the feeling, indeed, that it was decided to send out another patrol to the Umguza on the following Wednesday, and as I was anxious to see a good blow struck at them, I asked Mr. Duncan and Colonel Napier to give me another day’s leave of absence from my work of superintending the building of forts and patrolling along the Mangwe road, in order that I might take part in the engagement. At the same time I sent a wire to Captain Molyneux at Fig Tree, requesting him to forward instructions to Lieutenant Grenfell at Matoli to march back with the men of my troop to Mabukitwani, where it had been decided that we were to build a fort, and where I undertook to meet him, unless anything unforeseen should happen, on Thursday evening.

Thus on Wednesday morning, 22nd April, for the fourth time a small force marched out of Bulawayo, in order to try and dislodge the Kafirs from their position on the Umguza, in the immediate vicinity of the town. This patrol was put under the command of Captain Bisset, a gentleman who had had some previous experience of native warfare in Basutoland and Zululand.

The patrol consisted of twenty Scouts under Captain Grey; forty men under Captain Van Niekerk; twenty under Captain Meikle, and twenty under Captain Brand, making, with some twenty others unattached, about one hundred and twenty mounted men, with a Hotchkiss and a Maxim under Lieutenant Walsh. Besides these mounted troops, there were a detachment of one hundred colonial Kafirs and Zulus recruited by Mr. Colenbrander, and some friendly Kafirs who, however, were only armed with assegais, and who took no part in the fight. I was asked to take command of the Colonial Boys, which I could hardly do, as they had their own trusted officers with them, but I accompanied these gentlemen, and undertook to assist them in leading their men to the attack. Dr. Vigne went in charge of the ambulance waggon which accompanied the patrol.

After much valuable time had been lost in looking for the impi which was said to be behind the brickfields, but which as a matter of fact had never been there, we turned towards the Umguza, passing at the back of Government House. Here an accident occurred to the Hotchkiss limber carriage, which delayed us for more than an hour, and although the broken shaft was temporarily tied up with a chain, so that the gun could be drawn along, it was rendered useless for action until the damage done could be properly repaired.

On proceeding we changed our direction and made straight for the Umguza, and it was soon evident that the Kafirs intended to dispute our advance, as they commenced to fire on us from the low ridges covered with scrubby bush which here border the river on both sides. Captain Van Niekerk and his Africanders were soon hotly engaged on the left flank, and as the Kafirs were in possession of some ridges just in front of us as well, I was asked to advance with the Colonial Boys from the centre, and endeavour to chase them across the river. My instructions were to attack and, if possible, drive them before me, but to retire on the guns if I found them too strong.

The boys came on capitally, led by their officers, who were all mounted, and we soon drove all the Matabele in this part of the field through the Umguza, and following them up at once, pursued them for about a mile over some stony ridges covered with scrubby bush.

Up to this time I had not fired a shot, as I had been principally engaged in encouraging the Colonial Boys to come on quickly and give our enemies no breathing time. But by this time we had got right up amongst them, and I began to use my rifle.

A number of the Matabele had built little fortifications of loose stones near the bank of the river, from behind the shelter of which they fired on us; but the warlike Amakosa and Zulus charged them most gallantly, and engaging them hand to hand drove them out of their shelters into the river, and killed many of them in the water. Several of the Colonial Boys were here wounded with assegais and axes, but none were killed.

It was at this time that I saw John Grootboom, a Xosa Kafir—who has distinguished himself for bravery on many occasions both during the first war and the present campaign—galloping after a Matabele just in front of me, who was armed only with assegais and shield. As the horse came upon him he ducked down, and only just escaped a blow on the head from John’s rifle, which was dealt with such vigour that the rider lost his balance and fell off, and his foot catching in the stirrup, he was dragged along the road for some yards. If the Matabele had but kept his presence of mind and been quick, he might have assegaied his antagonist easily, and possibly would have done so had not Captain Fynn and myself been close to him.

We had now got the Matabele fairly on the run in our part of the field, and the only ones who were still firing at us were a party who had taken shelter in a bend of the river under cover of the bank, some three hundred yards ahead of us. I was just going with some of the Colonial Boys to dislodge them, when I saw Grey’s Scouts charging down on them from the other side of the river. Finding themselves attacked from this quarter, the Matabele left their cover and ran out into the open in large numbers, exposing themselves to a heavy fire which thinned their ranks every instant.

The position was now this.—The Matabele had been driven from the banks of the river, and two or three hundred of them, panic-stricken and demoralised, were running in a crowd across some undulating ground, but scantily covered with bush, and had only Captain Meikle and Captain Brand been sent in support of the Colonial Boys and the Scouts, they might have galloped in amongst them, and could not have failed to kill a very large number of them. But no; although these officers and their men were chafing and cursing at their enforced inactivity, they were kept idly standing round the Maxim doing nothing, which was all the more inexcusable as Captain Van Niekerk with his forty Africanders had by this time silenced the enemy’s fire on the left flank, and there was no farther apprehension of any heavy attack from that quarter. At any rate, one of the best chances of inflicting a heavy loss on the rebels which has occurred during the campaign was not taken advantage of.

At this time, that is just when Grey’s Scouts were driving the Matabele out of the river, some one told me that an order had come recalling the Colonial Boys, so I galloped along the line of those that were farthest in advance, and told them that the order had been given to retire. Then I thought that before going back myself I would gallop forwards and try and get a shot or two at some of the Kafirs armed with guns, who were retreating from the fire of Grey’s Scouts.

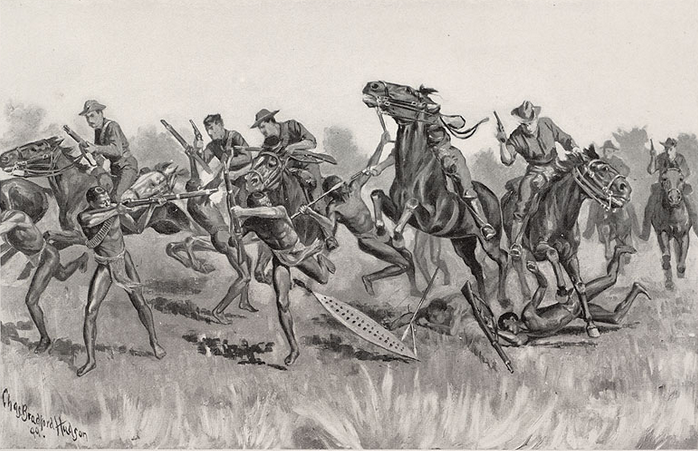

In front of me lay a piece of perfectly open ground extending along the Umguza, some 200 yards broad, whilst from the edge of the open to the left the country was undulating and very scantily covered with low bush. The pony I was riding was the same that had been lent to me on the previous Sunday, and he had proved himself so absolutely steady, with rifles going off all round him, and bullets pinging and buzzing past him, that the last thing I thought of was that he might now play me false and run away. However this is what happened. I had dismounted and was sitting down to get a steady shot when some one said close behind me, “Look out, they’re coming down on us from the left.” I did not know that any one was near me, but on getting up and looking round, saw one of the officers of the Colonial Boys—now Captain, then Lieutenant Windley—close behind me. At the same time I saw Grey’s Scouts retreating on the other side of the river, and recognised that Windley and I were a long way ahead of John Grootboom and five or six other Xosa Kafirs, who were the only members of the corps I could see, and who were also retiring; whilst I also saw that some of the Matabele we had been chasing had rallied, and seeing two white men alone, were coming down on us as hard as they could, with the evident intention of cutting off our retreat. However, they were still some 250 yards from us, and could I but have mounted my pony, we could have galloped away from them and rejoined the Colonial Boys easily enough.

A few bullets were again beginning to ping past us, so I did not want to lose any time, but before I could take my pony by the bridle he suddenly threw up his head, and spinning round trotted off, luckily running in the direction from which we had come. Being so very steady a pony, I imagine that a bullet must have grazed him and startled him into playing me this sorry trick at such a very inconvenient [Pg moment. “Come on as hard as you can, and I’ll catch your horse and bring him back to you,” said Windley, and started off after the faithless steed. But the brute would not allow himself to be caught, and when his pursuer approached him, broke from a trot into a gallop, and finally showed a clean pair of heels.

When my pony went off with Windley after him, leaving me, comparatively speaking, planté là, the Kafirs thought they had got me, and commenced to shout out encouragingly to one another and also to make a kind of hissing noise, like the word “jee” long drawn out. All this time I was running as hard as I could after Windley and my runaway horse. As I ran carrying my rifle at the trail, I felt in my bandoleer with my left hand to see how many cartridges were still at my disposal, and found that I had fired away all but two of the thirty I had come out with, one being left in the belt and the other in my rifle. Glancing round, I saw that the foremost Kafirs were gaining on me fast, though had this incident occurred in 1876 instead of 1896, with the start I had got I would have run away from any of them.

Windley, after galloping some distance, realised that it was useless wasting any more time trying to catch my horse, and like a good fellow came back to help me; and had he not done so, let me here say that the present history would never have been written, for nothing could possibly have saved me from being overtaken, surrounded, and killed. When Windley came up to me he said “Get up behind me; there’s no time to lose,” and pulled his foot out of the left stirrup for me to mount. Without any unnecessary loss of time, I caught hold of the pommel of the saddle, and got my foot into the iron, but it seemed to me that my weight might pull Windley and the saddle right round, so, as a glance over my shoulder showed me that the foremost Kafirs were now within 100 yards of us, I hastily pulled my foot out of the stirrup again, and shifting my rifle to my left hand caught hold of the thong round the horse’s neck with my right, and told Windley to let him go. He was a big strong animal, and as, by keeping my arm well bent, I held my body close up to him, he got me along at a good pace, and we began to gain on the Kafirs. They now commenced to shoot, but being more or less blown by hard running, they shot very badly, though they put the bullets all about us. Two struck just by my foot, and one knocked the heel of Windley’s boot off. If they could only have hit the horse, they would have got both of us.

After having gained a little on our pursuers, Windley, thinking I must have been getting done up, asked me to try again to mount behind him: no very easy matter when you have a big horse to get on to and are holding a rifle in your right hand. However, with a desperate effort I got up behind him; but the horse, being unaccustomed to such a proceeding, immediately commenced to buck, and in spite of spurring would not go forwards, and the Kafirs, seeing our predicament, raised a yell and came on again with renewed ardour.

Seeing that if I stuck on the horse behind Windley we should both of us very soon lose our lives, I flung myself off in the middle of a buck, and landed right on the back of my neck and shoulders. Luckily I was not stunned or in any way hurt, and was on my legs and ready to run again with my hand on the thong round the horse’s neck in a very creditably short space of time. My hat had fallen off, but I never left go of my rifle, and as I didn’t think it quite the best time to be looking for a hat, I left it, all adorned with the colours of my troop as it was, to be picked up by the enemy, by whom it has no doubt been preserved as a souvenir of my presence amongst them.

And now another spurt brought us almost up to John Grootboom and the five or six Colonial Boys who were with him, and I called to John to halt the men and check the Matabele who were pursuing us, by firing a volley past us at them. This they did, and it at once had the desired effect, the Kafirs who were nearest to us hanging back and waiting for those behind to join them. In the meantime Windley and I joined John Grootboom’s party, and old John at once gave me his horse, which, as I was very much exhausted and out of breath, I was very glad to get. Indeed I was so tired by the hardest run I had ever had since my old elephant-hunting days, that it was quite an effort to mount. I was now safe, except that a few bullets were buzzing about, for soon after getting up to John Grootboom we joined the main body of the Colonial Boys, and then, keeping the Matabele at bay, retired slowly towards the position defended by the Maxim. Our enemies, who had been so narrowly baulked of their expected prey, followed us to the top of a rise, well within range of the gun, but disappeared immediately a few sighting shots were fired at them.

Thus ended a very disagreeable little experience, which but for the cool courage of Captain Windley would undoubtedly have ended fatally to myself. Like many brave men, Captain Windley is so modest that I should probably offend him were I to say very much about him; but at any rate I shall never forget the service he did me at the risk of his own life that day on the Umguza, whilst the personal gallantry he has always shown throughout the present campaign as a leader of our native allies has earned for him such respect and admiration that they have nicknamed him “Inkunzi,” the Bull, the symbol of strength and courage. But Captain Windley was not the only man who performed a brave and self-denying deed on this somewhat eventful day, as I shall now proceed to relate.

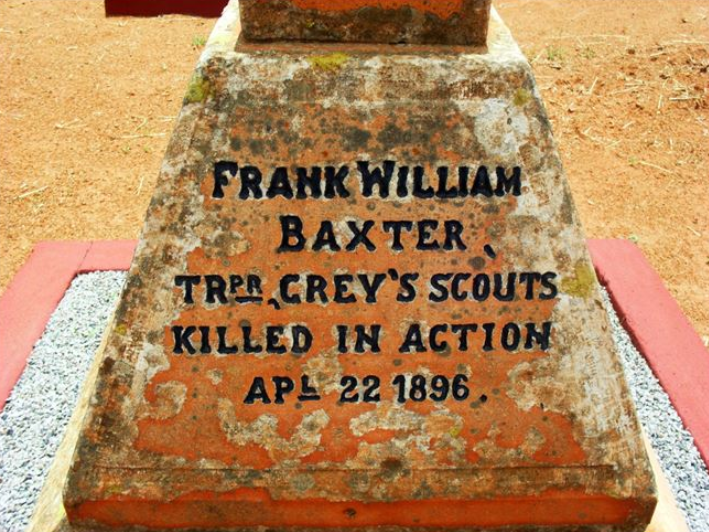

When the Scouts were recalled, and commenced to retire from the Umguza, after having driven a body of natives from its shelter, as I have already related, they were suddenly fired on by a party of Matabele who had taken up a position amongst some bush to the left of their line of retreat. The foremost amongst the Scouts galloped past this ambush, but Captain Grey with a few of those in the rear halted and returned the enemy’s fire. Trooper Wise was the first man hit, and seems to have received his wound from behind just as he was mounting his horse, as the bullet struck him high in the back, and travelling up the shoulder-blade, came out near the collar-bone. At this instant Wise’s horse stumbled, and then, recovering himself, broke away from its rider, galloping straight back to town, and leaving the wounded man on the ground. A brave fellow named Baxter at once dismounted and put Wise on his own horse, thus saving the latter’s life, but, as it proved, thereby sacrificing his own. Captain Grey and Lieutenant Hook at once went to Baxter’s assistance, and they got him along as fast as they could, but the Kafirs had now closed on them, and were firing out of the bush at very close quarters. Lieutenant Hook was shot from behind, the bullet entering the right buttock and coming out near the groin, but most luckily, though severing the sciatic nerve, just missing both the thigh-bone and the femoral artery. Nearly at the same time, too, a bullet just grazed Captain Grey’s forehead, half-stunning him for an instant. “Texas” Long, a well-known member of the Scouts, then went to Baxter’s assistance, and was helping him along, when a bullet struck the dismounted man in the side, and he at once let go of Long’s stirrup leather and fell to the ground. No further assistance was then possible, and poor Baxter was killed by the Kafirs immediately afterwards. Whilst these brave deeds were being performed, Lieutenant Fred Crewe, with some others of the Scouts, amongst whom I may mention Button and Radermayer, were keeping the Kafirs in check and covering the retreat of the wounded men. Just as Lieutenant Hook got near to Crewe, his horse was shot through the fetlock and buttock at the same time, and rolling over, threw Hook to the ground, causing him at the same time to drop his rifle. Hook got on his legs and was hobbling forwards when Crewe said to him, “Why don’t you pick up your rifle?” “I can’t,” was the answer; “I’m too badly wounded.” “Are you wounded, old chap?” said Crewe; “then take my horse, and I’ll try and get out of it on foot.” Crewe then assisted Hook to mount his horse, and fought his way back on foot, only escaping with his life by a miracle, keeping several Kafirs who were very near him, but who had no guns, at bay with his revolver, whilst he retreated backwards. So near were these men to him, that one of them, as he turned, threw a heavy knob-kerry at him, which struck him a severe blow in the back. Nothing could have saved him had not the Kafirs been constantly kept in check by the steady fire of Radermayer, Button, Jack Stuart, and others of the Scouts, and also by a cross-fire from some of the Colonial Boys, directed by Captain Fynn and Lieutenant Mullins.

The splendid gallantry and devotion to one another shown by Captain Grey and his officers and men on this day will ever be remembered in Rhodesia as amongst the bravest of the brave deeds performed by the Colonists in the suppression of the present rebellion. Such acts, too, speak for themselves, and bear eloquent if silent testimony against the cruel and malicious calumnies on the character of the white settlers in Matabeleland which have so frequently disgraced the pages of a widely-read, if generally-despised, weekly journal.

As soon as Grey’s Scouts and the Colonial Boys had reached the guns, these latter were limbered up and the whole patrol retired slowly on Bulawayo, the Matabele making no attempt to follow. Indeed their loss must have been severe, and had Grey’s Scouts and the Colonial Boys only been supported instead of being recalled, the Matabele would never have rallied, but would have been kept on the run and killed in large numbers by the mounted men. At least this is my view, and it has been thoroughly borne out by the experience gained in subsequent fights during this campaign.

Our loss on this day was, Baxter killed and Wise and Hook wounded amongst Grey’s Scouts, while five or six of the Colonial Boys were wounded, but none dangerously. Wise has long ago recovered from his wound, and Lieutenant Hook is on a fair way to do so. I have forgotten to mention that my horse must have been captured by the Matabele, as he did not return to Bulawayo, and has not since been heard of. The lucky savage into whose hands he fell became possessed at the same time of a very good saddle and bridle, and a brand new Government coat.