Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historic Events of Colonial Days, by Rupert S. Holland (published 1916).

Soldiers, both foot and cavalry, were landed on Long Island from the English fleet, and marched double-quick through the forest toward the small cluster of houses that stood along the shore where the city of Brooklyn now rises. They met with no resistance; for the most part these woods and shores were as empty of men as the day when Henryk Hudson first sailed up the river that bears his name.

The fleet meanwhile went up through the Narrows, and two frigates landed more soldiers a short distance below Brooklyn, to support those that were marching down the island. Two other frigates, one of thirty-six guns, the second of thirty, under full sail, passed directly within range of Stuyvesant’s little fort, and anchored between the fort and Governor’s Island. The English fleet meant to show their contempt for the Dutch claims.

What was Peter Stuyvesant doing as the frigates so insolently sailed past under his very eyes? He was a fighter by nature and by trade, as peppery as some of the sauces he had brought with him from the West Indies. The cannon of his fort were loaded, and the gunners stood ready with their burning matches. A word, a nod, a wave of the hand from Stuyvesant, and the cannon would roar their answer to the insolent fleet. And what would happen then? Fort Amsterdam had only twenty guns; and the two frigates sailing by had sixty-six, and the two other frigates, almost within sight, had twenty-eight more. Stuyvesant bit his lips as his gunners waited. The first roar of his cannon would almost certainly mean the ruin of every house in New Amsterdam.

Yet could the governor see the flag of his beloved New Netherland flouted in this fashion? Raging with anger, the word to fire trembling on his lips, Stuyvesant turned to listen to the advice of two Dutch clergymen who had hurried up to him. They begged him not to be the first to shed blood in a fight that could only end in their utter defeat. They were outnumbered, outmatched in every way. The governor knew this was so; no one in the colony indeed knew it better than he. “I won’t open fire,” he said, bitter rage in his heart, but he shook his fist at the white sails of the frigates.

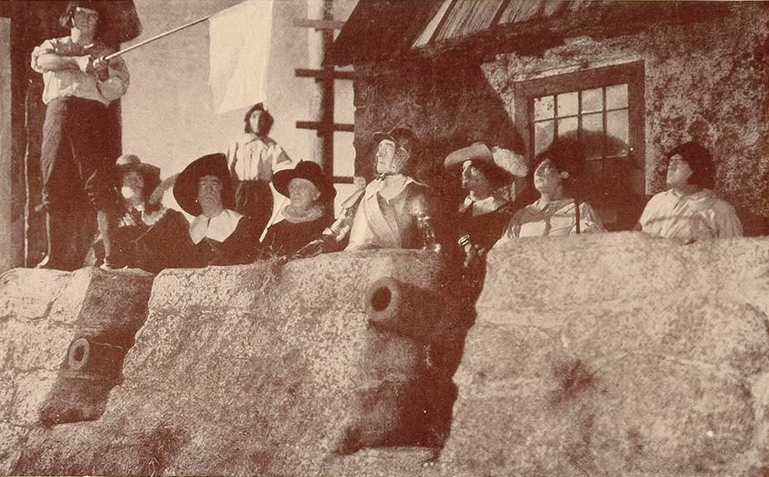

Stuyvesant left the rampart, leaving fifty men to defend the fort, and took the rest of the garrison, one hundred soldiers, down to the shore, to repel the English if they should try to land. He still had a faint hope that the English commander would make some terms with him that would allow him to keep the flag of Holland flying over New Amsterdam.

With this faint hope he sent four of his chief officers with a flag of truce to Colonel Nicholls. They carried this message from Peter Stuyvesant: “I feel obliged to defend the city, in obedience to orders. It is inevitable that much blood will be shed on the occurrence of the assault. Cannot some accommodation yet be agreed upon? Friends will be welcome if they come in a friendly manner.”

So spoke the Dutch governor, trying to be patient and reasonable, no matter how hard such a course might be for him. Colonel Nicholls, sure of his greater power in men and guns, cared not a whit to be either reasonable or patient. He sent back a determined answer. “I have nothing to do but to execute my mission,” he said. “To accomplish that I hope to have further conversation with you on the morrow, at the Manhattans. You say that friends will be welcome, if they come in a friendly manner. I shall come with ships and soldiers. And he will be bold indeed who will dare to come on board my ships, to demand an answer or to solicit terms. What then is to be done? Hoist the white flag of surrender, and then something may be considered.”

This haughty answer spread through New Amsterdam, and men and women rushed to the governor to beg him to surrender. Bombardment by the fleet would destroy all they owned, and doubtless kill many of them. Stuyvesant would have fought until his flag fell over a heap of ruins, but he knew that his people would not stand behind him. “I had rather,” he told the men and women as they thronged about him, “be carried a corpse to my grave than to surrender the city!”

The people went to the City Hall, and drew up a paper of protest to their governor. The protest said that the people could only see misery, sorrow, and fire in resistance, the ruin of fifteen hundred innocent men, women and children, only two hundred and fifty of whom were capable of bearing arms.

The words of the protest were true. “You are aware,” it said, “that four of the English king’s frigates are now in the roadstead, with six hundred soldiers on board. They have also commissions to all the governors of New England, a populous and thickly inhabited country, to impress troops, in addition to the forces already on board, for the purpose of reducing New Netherland to His Majesty’s obedience.

“These threats we would not have regarded, could we expect the smallest aid. But, God help us, where shall we turn for assistance, to the north or to the south, to the east or to the west? ‘Tis all in vain. On all sides we are encompassed and hemmed in by our enemies.” Ninety-four of the chief men of New Amsterdam signed this protest, one of them being Stuyvesant’s own son. In front of the governor were the guns of the English fleet, behind him was the mutiny of his own people.

New Amsterdam, only a cluster of some three hundred houses at the southern end of Manhattan Island, was entirely open to attack from either the East or the North River. An old palisade, built to protect the houses from Indian attacks, stretched from river to river on the north, and in front of this palisade were the remains of an old breastwork, three feet high and two feet wide. These might be of use against the Indians, but hardly against well-trained white soldiers.

Fort Amsterdam itself had only been built to withstand Indians, not white men. An earthen rampart, ten feet high and four feet thick, surrounded it, but there were no ditches or palisades. At its back, where the crowds of Broadway now daily pass, were a number of low wooded hills, with Indian trails leading through them. These hills, if held by an enemy, could easily command the fort. The little Dutch garrison hadn’t five hundred pounds of powder on hand. The store of provisions was equally small, and there was not a single well of water within the fortifications. To cap the climax, the garrison itself couldn’t be trusted; it was largely made up of the lowest class of the settlers, unfit to do any other work than shoulder a gun.

So Peter Stuyvesant saw that he must yield. He chose six of his men to meet with six of the English at his own bouwery on the morning of August 27th. There was little for the Dutchmen to do but agree to the terms their enemies offered them. The terms were that the province of New Netherland should belong to the English. The Dutch settlers might keep their own property or might leave the country if they chose. They might have any form of religion they pleased. Their officers, to be chosen at the next election, would have to take the oath of allegiance to the king of England.

Peter Stuyvesant only yielded because he saw that he must. He pulled down his flag that was flying above the ramparts, and “the fort and town called New Amsterdam, upon the island of Manhatoes,” as the treaty called it, passed from the ownership of the Dutch to that of the English. The officers and soldiers of the fort were allowed to march out with their arms, their drums beating and their colors flying. Most of the soldiers, many of the settlers, cared little what flag flew above their colony, so long as they were permitted a peaceful living, but at least one Dutchman, the governor, “Wooden-Legged Peter,” cared much when he saw the flag of the Netherlands come fluttering down.

The English Colonel Nicholls and his men marched into the fort and took possession of the government. They changed the name of the little settlement from New Amsterdam to New York, in honor of the Duke of York, who was the brother of the king of England. The fort was christened Fort James, the name of the Duke of York. Then Colonel Nicholls sent troops up the Hudson to take possession of the Dutch settlement of Fort Orange, and other troops to the Delaware River to raise the English flag over the small Dutch colony of New Amstel. The name of Fort Orange was changed to Fort Albany, the second title of the king’s brother, the Duke of York. The settlers there were well treated, and given the same liberty as was given the people on Manhattan Island. But those at New Amstel, on the Delaware, did not fare so well. Peter Stuyvesant indignantly reported that “At New Amstel, on the South River, notwithstanding they offered no resistance, but demanded good treatment, which however they did not obtain, they were invaded, stript bare, plundered, and many of them sold as slaves in Virginia.”

The flag of England now flew where the flag of the Netherlands had waved for half a century. There was no excuse for this seizing of the Dutch colony by the English. The Dutch were peaceful neighbors, fair in their dealings with the other colonies. But while the Dutch had not greatly increased the number of their settlers in the New World, the English had. New England was growing fast, so was Virginia, and in between these two English settlements lay the small Dutch one, at the mouth of a great river, and with the finest harbor of the whole seacoast. The English had cast envious eyes upon Manhattan Island. They wanted to own the whole seacoast; and so, being strong enough, they took it. And the Dutch, like the Indians before them, had to bow to the stronger force.

The Dutch Government in Europe called Peter Stuyvesant there to explain why he had surrendered his colony. He went to Holland and made his acts so clear to the States-General that they held him guiltless of every charge against him. Then he returned to New York and settled down at his bouwery, where he lived comfortably and well, like most of his Dutch neighbors, unvexed by the constant troubles he had known when he was the governor.

The colony of New York grew and prospered. The patroons lived on their big estates, rich, hospitable families, much like the wealthy planters of Virginia. The Dutch people in the towns were a thrifty, peaceable lot, glad to welcome new settlers, no matter from where they came. Most of the settlers came now from England, very few from the Netherlands; and in time there were more English than Dutch in the province. By the time of the Revolution the people of the two nations were practically one in their ideas and aims. Dutch and English fought side by side in that war, and helped to make the great state of New York. But the Dutch blood and the Dutch virtues persisted, and many of the greatest men of the new state bore old Dutch names. And so, though Peter Stuyvesant and his neighbors had to haul down their flag from their primitive ramparts at Fort Amsterdam, they and their descendants left their stamp upon that part of the New World they had been the first to settle.

5