Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Famous Discoverers and Explorers of America, by Charles L. Johnston (published 1917). All spelling in the original.

Once there lived in the island of Porto Rico, which became the property of the United States in 1898, a Spanish Knight who had fought against the Moors in Spain and who had helped to drive them from his native country. His name was Juan Ponce de Leon, and he was rich in slaves, in plantations, and in money.

The good knight was growing old. As he gazed in his mirror he saw that his once coal-black beard was now silvered with gray, that his head was not only bald, but also grizzled, and, as for his joints, well, he had strange rheumatic pains when he bent over, and he did not leap out of bed in the morning with the same spirit of enthusiasm that he had had twenty years before.

It is no wonder that this wrinkled soldier gave eager ear to the remarks of a native chieftain, Atamara, who one day said to the gray-haired veteran:

“I see, good sir, that you are nearing a time when you will have to bid farewell to all your earthly possessions, which will, I know, be far from pleasing to you. If you sail to the westward, you will find a fountain whose waters will restore the full vigor of youth. No matter how old you may be, should you but drink of this marvelous spring, you will be again twenty years of age. Your aches and pains will disappear, and you will enjoy life even as you did when a stripling.”

Ponce de Leon pricked up his ears at this, and eagerly questioned the chief concerning the direction which the fountain lay from the Isle of Porto Rico.

“It lies towards the northwest,” said the Indian. “Here a man and a woman, called Idona and Nomi, who had grown old together, came down to drink. Filling a pearly shell which lay near the water, first Nomi handed it to Idona, saying:

“‘Drink, my love, that I may know thou wilt not part from me forever, for I have heard from the wind that this is a magic fountain where the water has the power of returning one’s youth.’

“Idona drank, then turned and filled the cup for his mate. A marvel now came to pass. There stood Nomi, beautiful as in her youth; garlanded, too, with flowers as when Idona had first seen her, and facing her was her lover in all the glory of his young manhood.

“And, because these two had been so faithful to their pledges and had borne the pains of life so bravely together, the Spirit of the Earth led them to her own home, where they dwelt happily ever afterwards.

“But once in twelve moons they come to the fountain to drink together of its waters.

“This is the legend of the water,” concluded Atamara,“as it has been known amongst us from a time so far away that our wise men cannot measure it.”

Nowadays no one would give credence to such a legend, but those days were different from the present. For had not hundreds of Spaniards believed in the El Dorado, or gilded man, and had not they followed De Soto in order to view him? So the Knight of Spain asked many questions of Atamara concerning his knowledge of the land where was the Fountain of Youth, and he learned enough to satisfy himself that many unexplored islands and seas lay to the northward, which were only waiting for the eyes of some venturesome Castilian. He still had an iron constitution, built up by sound habits, military training, and temperate living; and he felt that he was not yet too old to use his good sword to carve out a greater dominion in new territories. On the other hand, he had reached the downward turn of life so that this tale of the Fountain of Youth appealed to him the more he pondered upon it; and he determined to go and seek for this mysterious water, even as De Soto had sought for the Gilded Man.

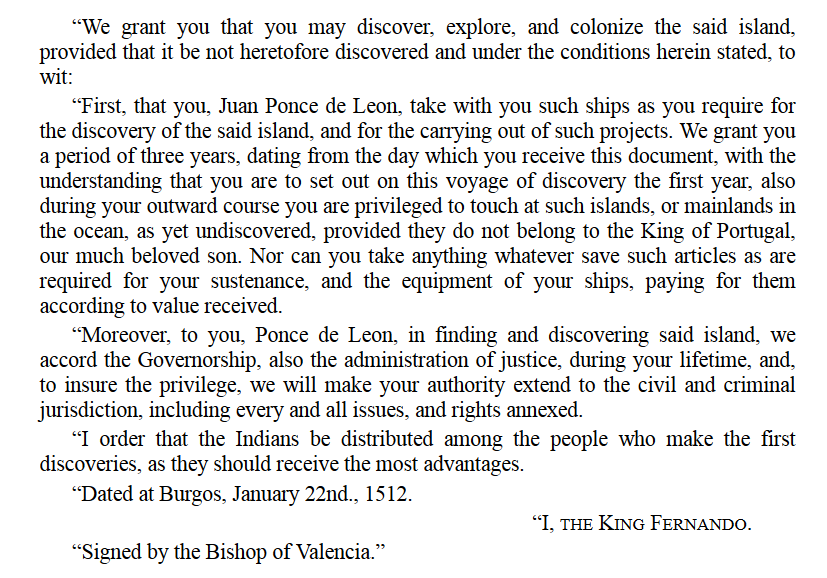

The King of Spain was quite ready to grant this knight permission to discover, explore, and colonize the fabled land of which De Leon now wrote him, and sent him a letter which ran as follows:

“To the Knight Don Juan Ponce de Leon. Inasmuch as you, Juan Ponce de Leon, have sent and asked permission to go and discover the Island of Biminin, in accordance with certain conditions herein stated, and in order to confer on you this favor:

De Leon overhauled his caravels, accumulated stores of arms, provisions, gifts, and trinkets of various kinds that would be suited to the tastes of the Indians whom he should find in these lands which he might discover, and arranged his home affairs. He had three caravels in all, and three hundred sailors and soldiers. Besides these, were several priests, for whose accommodation a chapel was built upon the after deck of the Dolores, the largest vessel. All things were now ready, and, bidding his good wife, the Dona Dolores, farewell, the Spanish adventurer turned the prow of his flagship towards the west, and sailed through azure seas, whose very fish were rainbow tinted, in quest of the Fountain of Youth.

The air was balmy, scented with the sweet odors of fruits and flowers, and fragrant with the spices of mango trees. The vessels drifted onward from one fairy-like islet to another, at all of which they made a brief stay, searching for that marvelous fountain of which the Indian had spoken.

Brown-skinned natives came from the forests, bearing gifts of precious stones, of fruit, and of beauteous flowers, for which they refused any recompense. White beaches glistened in the tropic sunlight as if their sands were polished grains of silver, and, as the caravels luffed under the lee of some of these palm-studded isles, the sailors saw quiet coves, shining like polished mirrors, into which crystal streams gurgled with murmurs almost human.

The Castilians were charmed with the beautiful scenery, and many said: “Surely in this land of peace and beauty there must be a Fountain of perpetual Youth.”

So they kept onward towards the north, ever looking for the marvellous water which was to turn their grizzled leader into a youth again.

The sailors gazed at the many birds which fluttered in the palms and sometimes hovered near their ships. There were white egrets, or herons, parroquets with green and yellow plumage, pink curlews, and flamingos with scarlet feathers and long curved bills. There were great sea turtles splashing in the shallows with huge, flabby feet, and gray sharks which whirled about amidst the foam in eager search for their prey.

Everywhere the natives were friendly, and, when asked if they knew aught of the Fountain of Youth, would shake their heads. Vainly the Spaniards drank of all the springs and the rivulets in these tropic isles, for none seemed to possess the wonderful healing properties for which they longed. The brown-skinned islanders knew little of Atamara’s legend of the fountain, but they spoke of a great land lying far beyond, where perhaps the wondrous water might be spouting. It was a fine country, said they, called by the musical name of Florida.

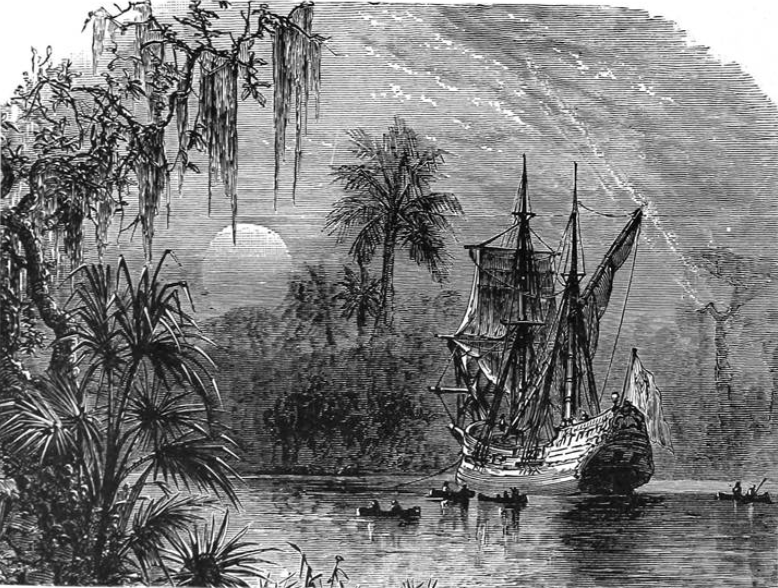

One moonlight evening, as De Leon sat upon the high deck of his caravel, when his vessels threaded a channel between two shadowy islands upon the port and the starboard, suddenly, far, far in front of him he beheld a brownish gray strip of country. It was an hour when revery would take the form of dreams, and, fearing that the vision of coast and headland, gulf, bays, palm trees and ports-of-refuge might be some delusive vision of the brain, he turned to his companion, Perez de Esequera, saying:

“Is it true that I view the shadowy sea-coast of some undiscovered land? I see great bays, indentations, and projections. I believe, good Perez, that we are nearing a shore from which many Spains, nay, all of Europe might be carved and scarcely missed. Pray that the saints shall guide us to the land of Bimini and to that wondrous fountain of perpetual youth!”

“Indeed, good Knight,” replied his companion. “I, also, see this vision. It may be a mirage, but I feel that soon we shall find this country of which the natives tell. Let us be optimistic!”

Next day the vessels were headed towards the north, and, with a stiff breeze filling the bellying canvas, made progress onward. During the night, the sailors of De Leon’s caravel heard the distant booming of breakers, and awakened their leader. The good knight called to his sailing-master to make soundings, which showed that they were in shallow water. So the anchors were let go, the sails were furled, and the vessels lay waiting for the coming of the day.

Dawn reddened in the east, and, far to the north and south of the anchorage, stretched a multitude of sand dunes. The surging billows of the Atlantic threw white wisps of spray upon a long yellowish beach, beyond which was a background of dark green forests. From the masthead a sailor called out that he saw a winding river, coursing through grassy marshes, which grew broad and green-gray as it reached the ocean. It was Palm Sunday, March the 27th., 1512, so the Castilians sang the Te Deum and, with ringing cheers, gave voice to their pleasure in finding the fabled land of Florida.

When the vessels neared the beach, next day, the adventurers saw that there was little here but a succession of sand hills. So the Spaniards coasted along by the booming surf and at length reached a sheltered bay which they called the Bay of the Holy Cross. Many native canoes were seen disappearing into narrow creeks among the marshes, so it was apparent that the Indians had no desire to become acquainted with these strange mariners in the queer-shaped caravels. The ships anchored and that night De Leon called his captains and lieutenants on board his flag ship for counsel. It was decided that on the morning a landing should be made, in force, and that formal possession should be taken of this soil in the name of King Ferdinand of Spain.

The next morning was the second of April, a time when the foliage of Florida is at its best. As day crept on, boats were lowered along the sloping sides of the little caravels, which rapidly filled with armored men upon whose greaves and breastplates the sunlight flashed and gleamed with silvery reflections in the green-black water. Waving plumes and crimson scarfs tossed in the morning breeze, while high above all gleamed the golden cross borne by the Chaplain, good Father Antonio. The commander had decreed that all should appear in the best of armor and equipment so that the honor due the King of Spain by his followers should be ample and sufficient.

The tide being full, the boats landed high up on the shore, Ponce De Leon leading the way, and being the first to step upon the soil which would thenceforth be his by decree of his Sovereign. Halting, the cavalier waited for Father Antonio with his cross, before which, on bended knee, he gave thanks to God for his great mercy in bringing him safely to this goodly land.

Now all disembarked, and, while trumpets sounded and drums beat, formed a procession headed by the priests, the cross, and Ponce de Leon with his banner. Marching to the roll of drum and the blare of bugle, the cavalcade went some distance up the beach to a spot where the priests had erected the chapel altar, decorated with sacred emblems and votive offerings. This was in the square of an Indian village. The golden cross was placed in a position facing the morning sun and the soldiers knelt in a semi-circle around it, as service was held to commemorate this auspicious event.

Save for the deep booming of the sea, and the song of a mocking bird, there was silence. The Indians peered at the strange sight from behind trees and bushes in the neighboring forest, and, perceiving that the fair-skinned strangers were engaged in some ceremony or proceedings, they looked upon the crouching Spaniards with expressions of awe.

The mass was soon ended, and Ponce de Leon took formal possession of the country in the name of his sovereign, proclaiming himself, by virtue of the royal authority, Adelantodo of the Land of Florida. Then a fanfare of trumpets rent the air, mingled with the cheers of the soldiers.

A small stone pillar was now set up, which had been brought from Porto Rico for that purpose, and upon which was carved a cross, the royal arms, and an inscription reciting the discovery of Florida and its possession by the Crown of Spain.

Although De Leon felt that he was really the first Spaniard to find this country, such was really not the case, for the outline of the peninsula is plainly drawn in an old map published in the year 1502. To this discovery little attention seems to have been paid at the time, for it was a period when explorers were most anxious to find gold and pearls and there was nothing to fix particular attention to this new coast. Thus Ponce de Leon’s vaunted first vision was really a rediscovery of what an earlier and equally valiant Castilian had seen.

The Spaniards, who had landed, it seems, not far from the site of St. Augustine, found, when they attempted to search for the Fountain of Perpetual Youth, that the natives did not have quite as good an opinion of their mission as they could wish.

After they had sailed from the Bay of the Holy Cross the wise men of the Indian village concluded that the stone pillar represented something inimical to their own rights of possession, so they had it taken to the deepest part of the bay and there thrown overboard. Previous to this they had vigorously protested against the invasion of their peaceful country. Yet no blows had been struck.

The caravels headed down the coast with fair wind behind them and, not far from the southern point of the island, which formed the seaward barrier of the Bay of the Holy Cross, they saw a curious spot upon the surface of the sea where the water boiled like a caldron, or as if some mighty fountain flowed upward from a hole in the bed of the ocean. This is a natural well in the Atlantic, quite similar to those on land, and can still be seen by sailors off the Florida coast. There were great schools of fish nearby, and many were captured in nets as the vessels drifted slowly upon their course.

The voyagers coasted along the low-lying shore, admiring the view, and finally saw a canoe approaching in which was a handsome youth, the messenger from a native chieftain Sannatowah. He bore a missive to the effect that, if the strangers came in peace, he was ready to meet them in the same spirit, also; but if they came not with such intent, it would be best for them to remain on board their floating houses, for there were as many warriors in the land as there were palm trees in the forests.

“How shall it be known whether we come in peace or in war?” asked Ponce de Leon.

“By this,” answered the herald, touching the bow which was slung over his shoulder, “if it be war. Or this,” laying his hand upon a green branch thrust in his girdle, “if it be peace. There are eagle eyes watching on yonder shore, and, whichever I hold up, the message goes straight to Sannatowah!”

“And if I let you make no sign nor go back, what then?”

“War!” was the answer.

A smile came to the serious countenance of the Spanish seeker for the Fountain of Youth as he said:

“I pray thee, then, young sea eagle, go to the prow of my ship and hold up the green bough of peace. I pledge you my sacred word that there shall be peace between thy people and mine as long as it is in my power to have it so. Tell me if there be any answer from the shore and if all is well. Tarry with us, so as to be our herald to your cacique.”

As he ceased speaking, the youthful Indian went forward, and, standing upon the bowsprit, waved his green branch first towards the south, next to the north, and then towards the sky. This over, he came back to the after deck, saying:

“All is well. Sannatowah and his people will greet you as friends and as guests.”

The Spaniards soon went ashore, greeted the Indian chieftain, and were told by him that, two days’ easy journey to the westward, lay several great springs and a mighty river, the beginning and end of which was unknown to him. One of these springs, said he, was in the territory of a tribe with which they were now at war; but, when he was a youth, there had been peace, and he had often visited it. This spring was deemed to be sacred. It was a great fountain which welled up from the depths of the earth and was apparently bottomless. Its waters were as clear as azure, so that one could see far into the pearly depths.

“I drank not of it,” he continued, “for the wise men of the tribe said that it was forbidden by the Great Spirit, except to one of the tribe in whose land it was. The fountain is in the country of Tegesta.”

Ponce de Leon tarried quietly in the bay for several days; but finally landed his men, in order to travel to the place where lay this wondrous fountain. He had ten horses on the caravels and one mule. These were lowered overboard and swam ashore, which occasioned much surprise and astonishment among the natives, who viewed these strange animals with both fear and distrust.

When Father Antonio’s long-eared mule climbed from the ocean and struck the solid earth with his hoofs (the first of his kind to come to Florida) and then opened his mouth for one long, piercing bray, all the natives took to the woods in impulsive flight. It was some time before they dared to return.

Sannatowah was eager to befriend De Leon, and sent him guides to pilot him to the place where lay the great river and the crystal spring; and, although usually averse to such labor, a number of redskins went along as porters, agreeing of their own free will to go at least as far as their own boundaries. Everything was soon ready, the trumpets blared out their clarion notes of warning, and the march began.

Through forests of great oaks, magnolias and palm trees which hung with streamers of long, gray moss and matted vines, the Spaniards wended their way, startling many a shy deer from the leafy coverts and once or twice a great brown bear, which lumbered away, snorting with fear. Mocking birds trilled at them from leafy branches, and squirrels chattered and scolded from fallen tree trunks.

Carrying his helmet at his saddle-bow, so that he might feel the refreshing breeze, De Leon rode at the head of the little column of horse and foot until they came to a place in the forest where a great tree lay prostrate over the trail.

“This,” said the native guides, “is the border of our lands. Beyond is Tegesta. We can go no farther, for, while the flower of peace blooms, there is a truce between ourselves and those who live beyond.”

So the Spaniards made camp, but next morning they pressed onward into the wilderness, and, passing around a great cypress swamp, suddenly came upon an Indian village named Colooza, near a large lake. They were met with a shower of arrows, but, clapping spurs to their horses, soon drove the redskins behind a rude stockade which surrounded their thatched huts.

De Leon flung himself from his horse, and, regardless of the arrows which were singing around him and were glancing from his steel breastplate, he led a charge upon the gate, with a wild cry of “St. Iago and at them!” With his battle-ax he swept an entrance to the palisade, and then, dashing in, followed by his men, the village was soon cleared of all but five of the native Floridians. These, apparently awed by the invulnerability of their opponents, gave in and surrendered. They were compelled to go along with the Spaniards as guides.

Passing through a country of well-tilled fields and gardens, where were picturesque clusters of native houses, the discoverers came to the waters of a great lake which was so wide that the woods were scarcely distinguishable upon the opposite shore. This was Lake Munroe, a broad expanse of the St. Johns River, which enters it at one end and flows from it at the other. De Leon here halted, sending the captured natives onward to find the chief of this country, telling them to assure him that the white men were peacefully inclined and were in search of the fabled and mystical Fountain of Perpetual Youth, which they had heard was in the territory over which he held dominion.

At nightfall, one of these native runners appeared at the camp, bearing the reply of the great chief Olatheta, which was that he was delighted to learn that the strangers did not wish to war with him and requested that their leader should meet him at the council house upon the following day.

Ponce de Leon was overjoyed. Now he was nearing his goal, for he believed that the Fountain of Perpetual Youth lay only a few leagues before him. Eagerly he awaited the morrow, and, at the time set for the advance, heralds came from Olatheta to conduct the Spaniards to their chieftain.

The Castilians soon came upon a great collection of dwellings, many of which were quite large, and before the largest of all was the chieftain with his principal men. As they entered the town, the signal was given for the trumpeters to blow and the drums to beat. This caused great fear among the natives so that many ran away; but, seeing that there were no signs of hostility on the part of the strangers, they resumed their wonted attitude of stoical reserve.

“Pray, why have you come to this country?” asked Olatheta. “Are you peaceful, or are you warlike?”

Ponce de Leon bowed.

“I am the servant of a Great King beyond the water,” said he, “and he has given me the Governorship of these islands. So I have brought with me a holy man to teach you the true religion, and, as I have heard that you have here the Fountain of Perpetual Youth, I would like to visit it and to drink of its wonderous waters.”

Olatheta smiled, as he answered:

“There is a great fountain near at hand, which we all reverence and hold sacred. Yet, because my people have transgressed the proper laws of our tribe, the Great Spirit has taken much of its virtue from it. If, however, you wish to visit it, I will willingly accompany you. This holy man of yours may induce the great God to restore its power, which will be such a great blessing to my people that they will all rejoice at your coming, instead of being angry with you, as many are now, because of your attack upon Colooza.”

“Let us journey to this spring immediately,” said De Leon with enthusiasm. “Good chieftain, lead on!”

Olatheta arose, and, beckoning to the Spaniards to attend him, walked rapidly away. The Castilians followed, surrounded by a vast multitude of natives, who crowded around them in wonder and curiosity. As they wound through the thickets, Father Antonio’s mule startled every one with a series of the most ear-piercing brays, which caused an instant panic among the Indians, coupled with loud laugher from the soldiers.

“By the Saint of San Sebastian,” cried a Sergeant, called Bartola, “were that mule mine and were this indeed the fountain whereof we are in search, I should see to it that he drank not a drop of its waters.”

“Why so?” asked a smiling comrade.

“Why? A pretty question truly. Because there would be no place for any sound on earth, if the waters would have such virtue to increase vigor as they are said to have. All would have to fly before the thunderous braying of yonder ass.”

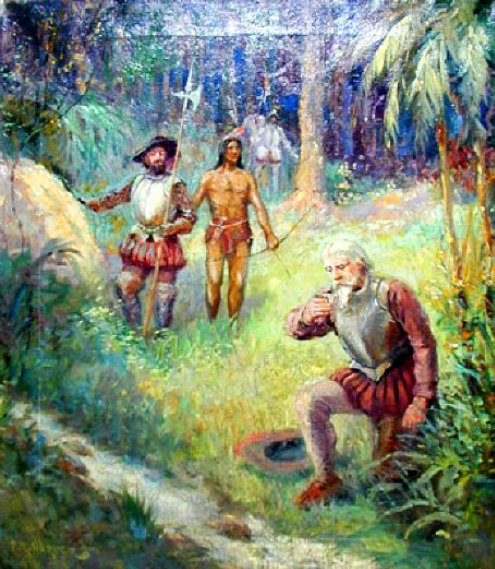

The cavalcade passed onward, and, nearing a grove of stately trees, the eager Spaniards saw a fountain such as they had never seen before in any other land. There was a brim as round as a huge cup, and inside were waters as clear as crystal, which boiled up from depths lost in inky shadows, and ran over the edge into a little water course, which gushed and bubbled towards the lake.

“Hurrah!” cried the eager De Leon. “It must indeed be the Fountain of Youth! Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!”

The day was a beautiful one. Bright birds darted from the waving branches, the sun shone brilliantly upon the armor of the Spanish adventurers, as, with the horsemen in advance, clad with plumed helmets, silver shields, upon which were emblazoned red lions, and with sword and battle-axe clanking against their armored legs, the Spaniards neared the gushing waters of the fountain.

In front of all was the good Father Antonio, who, holding with one hand the bridle-rein of his dun-brown mule, raised the other in blessing. The Indians crowded around him, awed by the sonorous Latin, and, as he finished his benediction, Olatheta stepped forward and filled an earthen cup, which he had brought, with water dipped from the fountain. Turning about he handed it to Ponce de Leon.

Smiling, and with a trembling hand, the good knight raised the cup to his lips. The cool liquid gurgled down his bronzed and weather-beaten throat. Yet—oh! sad and distressing to relate! No part of his grizzled exterior changed to the freshness of youth.

As he was raising this goblet to his lips, his companions rushed tumultuously to the fountain and buried their heated faces in the clear and sparkling water. They drank deeply, and in silence awaited the beginning of miracles, each with eager eyes fixed upon his neighbor.

Again, alas! The miracles came not. Beards of grizzly gray remained the same. Wrinkles did not disappear, and stiffened joints still moved with the same lack of spring as of yore. Alack and aday!! The fountain had lost its charm and was not the fabled water of perpetual youth.

The silence was broken by the solemn voice of Father Antonio:

“God’s will be done!” cried he. “Blessed be His holy name!”

In sorrow and with downcast faces, the Spaniards turned about, and wearily, dejectedly, mournfully, wended their way back to the camp of the friendly Olatheta.

The good Knight Ponce de Leon traveled through much of this beautiful land of Florida, fought many a stiff fight with the native inhabitants, and finally sailed back to the isle of Porto Rico, bearing marvelous tales of this land of promise, but no water which would restore the agèd to youth and beauty. He journeyed to Spain, was received right graciously by the King, and came back to his island home, expecting to remain there in peaceful pursuits, until his demise.

Yet, still hoping to find that mystical and fabled fountain, he finally fitted out two caravels, and, with a larger force than had followed his banner in the first expedition, resolved to again explore the western coast of beautiful Florida.

This journey was to be his undoing. At every point naked savages fought desperately against his mailed warriors. In one of these encounters he was attempting to rescue one of his comrades, when he was hit by an arrow in the thigh. The barb penetrated the protecting armor to the bone. He was rescued by his faithful followers and was carried to his ship, weak and fainting from the loss of blood. It is said by some, that, although the arrow was withdrawn, a part of the arrow-head, which was of flint, did not come wholly away.

Suffering and delirious, the brave old navigator was borne to the harbor of Matanzas in Cuba, where was a settlement which he, himself, had founded. His adventurous companions lifted the pallet upon which he lay on the upper deck, where the cooling breezes might alleviate his fever, lowered it into a boat, and, when the shore was reached, carried him tenderly into an unfinished house, which he was having constructed. They brought his suit of mail, his banner, and his sword, placing them around him so that he might feel at home. Delirium now seized the care-worn explorer, and thus he lay for days, as, in fancy he saw himself a boy again, climbing the bold rocks of the Sierras after young eagles, contending in the courtyard with his brothers, or chasing the brown deer in the leafy forests.

Then the camp and battle scenes passed before his eager vision; voyages over vast seas among beauteous islands; expeditions through palms and moss-grown mimosas; journeying to the villages of brown-skinned natives.

One night, peace came to the old warrior, and there was weeping and sorrow among his staunch and battle-scarred companions.

They carried the body of the good knight to the Isle of Porto Rico, where they first gave him a sepulchre within the castle, but eventually his ashes were deposited beneath the high altar of the Dominican church in San Juan de Puerto Rico, where they rested for more than three hundred years.

When the American forces invaded the country in 1898, and took it away from the rule of Castile, his remains were placed beneath a monument, upon which was carved the trite but appropriate saying:

“This narrow grave contains the remains of a man who was a lion by name, and much more so by nature.”

5