Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Shots Fired in Anger: A Rifleman’s-Eye View of the Activities on the Island of Guadalcanal, by Lt. Col. John B. George (published 1947).

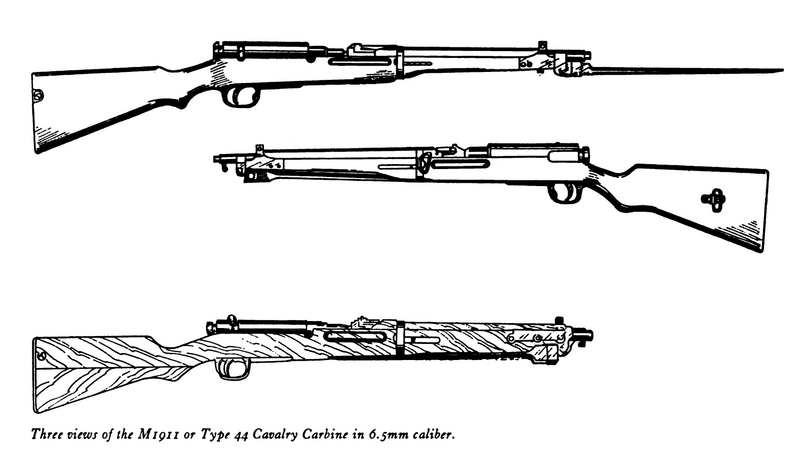

The Model 44 6.5mm Carbine

We had to wait until near the ending of the Guadalcanal operation before we were to come upon the most outstanding evidence of Japanese enthusiasm for cold steel. The astounding fact that bayonet fittings were used on light machine guns was discovered in the beginning, when we saw the first captured weapons on Lunga Beach, but it was not until the Cape Esperance show that we were to come across the Model 44 (1911) cavalry carbine, which had a bayonet permanently attached to the barrel, like a jack-knife blade, making the carbine muzzle-heavy and clumsy beyond belief.

This gun was meant to be used by mounted troops, and by a few Infantrymen who were in jungle areas. It had a feature of handiness for jungle work in that it was not necessary for the soldier to have a long bayonet scabbard attached to his belt. (American doughboys moving in jungle country often fastened their bayonets to the underside of the forends on their Garands — to dispense with the need for carrying that unhandy item.) But with all of its other faults, and from the viewpoint of military common sense, the adaptation was unthinkable.

It was a carbine almost exactly the same as the M38, (1905) carbine — from the buttplate to the lower band, that is. Between those areas the differences between it and the regular carbine were small, consisting of a trap in the buttplate, unnecessarily complex in design, which permitted a cleaning rod to be carried within the buttstock; and a groove cut four-and-a-half inches back from the upper band into the bottom of the forend, which provided a nestling-place for the last few inches of bayonet when it was folded back.

Yes, the bayonet folds back under the stock like the blade of a pocket knife.

The front end of this weapon, five inches back from the muzzle, was much modified in order to accommodate this weird looking device. The front sight was moved back to a position 3″ from the muzzle, and a massive forend tip was installed, made of solid steel, and containing a female hinge-half and two lock studs; one of them forward of the hinge under the muzzle, another an equal distance to the rear. These lock studs’ function was to hold the bayonet in the fixed, folded position — about one inch to the rear of the hinge. All of these devices, hinge and studs alike, were centered on the underside of the forend piece, which must have weighed at least a pound.

A poinard type bayonet, triangular in cross section with a deep blood-run on the upper side, was fitted to the rifle by means of a male hinge-half at its base, which fit into the massive female hinge-half located two inches back from the muzzle on the underside of the special forend. It was secured there by a large rivet which was extended on the right side to form a hook of the type found on nearly all Japanese bayonets; which hook is used for stacking the weapons and also in bayonet fighting, to wrench a weapon out of an opponent’s hands. On this carbine the hook stuck out to the right and forward at all times. On other rifles the hook is with the bayonet, pointing downward and forward.

The bayonet of the M44 measures sixteen inches overall, with a blade length of fourteen inches. The two inch section at the rear was enlarged and contained a heavy latch mechanism which was unlocked by means of a knurled-top push button sticking out from the right side. This locking action was automatic when the bayonet was swung forward or backward into either the ready or the retracted positions and pressed strongly upward. As far as the qualities of ruggedness and dependability are concerned, the device could be called a masterpiece. But its overall weight seems excessive, and it throws the little carbine completely out of balance, making it muzzle heavy and slow-pointing, even for a man used to the weight of match rifles, which the Japanese certainly were not.

Another outstanding disadvantage also accrues from the fact that the bayonet on the carbine is not removable and cannot serve its owner as a knife or bolo apart from the weapon. The edges of the bayonet are of necessity dulled, because part of it will rest in the palm of the hand when it is not extended. A certain amount of effectiveness is thereby lost.

The lower band is creased inward at 6 o’clock to admit the bayonet into its inletted groove when folded back, otherwise there is no change from the M38. Its really just a hashed up version of the same gun.

The particular carbine of this type which I first examined was hanging, oiled and well-cared for, in a banana leaf lean-to where the floor space was filled by three bodies lying side-by-side in three different stages of decomposition. One had been dead a month, another a week, and the third no more than three days. It took many days’ exposure to the air and sunlight before the smell left the wood of the stock and I could get my face down on it to aim. This carbine shot pretty good — the ponderous weight forward was somewhat steadying.

But this weapon was about the poorest example of ordnance design that I had ever seen. Perhaps it should be called “ordnance butchery” because without the M44 modification of a permanently fitted bayonet, the M38 carbine was a pretty nice little gun. But I wouldn’t give hell-room to the Official Cavalry Weapon of the Japanese Imperial Armies.

(Continue to Part 5)