Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Shots Fired in Anger: A Rifleman’s-Eye View of the Activities on the Island of Guadalcanal, by Lt. Col. John B. George (published 1947).

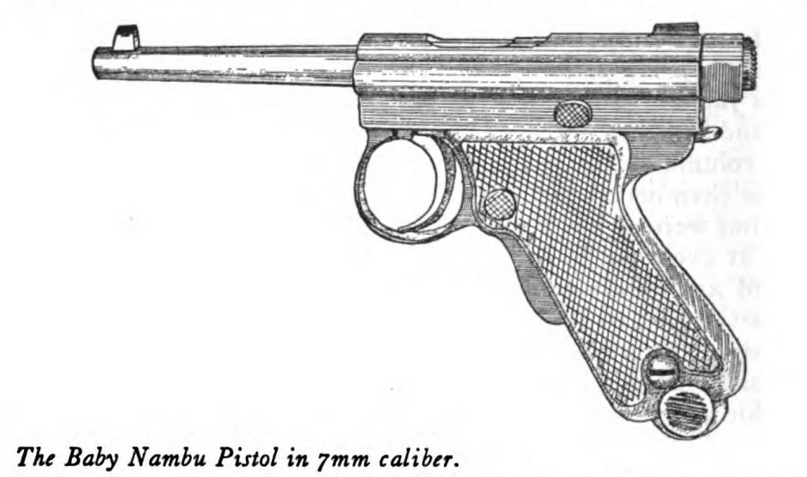

The “Baby Nambu” 7mm and the Type 94 8mm Pistol

My impression that the Nambu 8mm pistol was the best handgun which the Japanese had to offer our souvenir hunters held until after the Cape Esperance venture was well under way. By the time we were relieved at Hill 27 there were several such pistols in the hands of members of the battalion and I had had ample opportunity to look them over. Smooth-finished and trim in appearance, they seemed the nicest of all items of enemy equipment we had seen. Every man in the outfit wanted one for himself and there were always great expressions of disappointment each time a soldier opened up a leather or rubberized canvas holster lying in one of the battlefield areas and found it to contain a Model 94 — rough-finished and loose fit.

But when we got to Cape Esperance proper (on the day we were shelled by our own Navy) I saw the neatest souvenir of all. It was the Japanese 7mm Nambu — usually spoken of as the “Baby Nambu.” A sergeant of Company “H” found the first one any of us had seen, on a Jap he killed that morning.

We had started moving down the beach trail in pursuit of the defeated Japs, the assault echelon driving straight ahead with no flank security whatsoever. Colonel Gavin had told us to trot down the trail as fast as we could and not to worry about our right flank which faced the jungle and hills. We naturally had no worries over our left, which, from our feet to the ocean, was no more than a thin band of coconut trees, seldom wider than twenty yards. We slowed down only once when Danny Prewitt was halted for a few moments during the early morning on that trail but soon he got through with a little shooting and on we went. Near the rear of the column the men had more time to look around to right and left, checking their flanks for safety’s sake. The sergeant was doing that very thing when he came upon the Jap with the Baby Nambu pistol. This Jap had huddled behind a tree not more than fifteen feet from the trail, concealing himself in the low undergrowth.

All that the sergeant could see of the Jap was his peaked cap sticking above the weeds, but it was enough to allow him to aim his Tommy gun and let fly a few rounds — which took good care of things.

The sergeant had assumed that the Jap had just moved into his position at the side of the trail a few seconds before he had been detected, but an examination of the Jap’s weapon — a neat little pistol of a type which was instantly recognizable as a smaller version of the Nambu — proved otherwise. The pistol had been in the Jap’s hand at the time he was killed, and the eight cartridges which were found on the person of the Jap, in the pistol, and on the ground near the tree, were each dented deeply in the primer by several blows of the firing pin.

This Jap had taken up a “sniper’s” position on the trail, sitting there and ineffectually snapping his weapon while the whole front of the column had gone by. All of the cartridges had been loaded into the chamber several times — their cases were badly scored and their rims were nicked by the ejector. Undoubtedly the sniper had aimed at everyone in the column who looked like an officer and snapped away bravely, but his ammunition had let him down. The cartridges had been handled in such a way as to remind me of those in the revolver of an old Chicago police friend of mine. They had evidently been left in a weapon which had been drenched with thin machine oil and the primers had been completely deadened by oil penetration. That the fault did not lie with the weapon was attested by good, deep firing pin impressions.

I never did get the story of whether or not the Japanese were generally ignorant of the effect of oil on small arms ammunition, but I have since come across several other instances which would tend to prove that they were. But whether ignorance or a shortage of good ammunition was responsible, it is almost a certainty that the deficiency saved someone’s life. At a maximum of twenty feet it would be difficult for a Jap to miss a standing man.

The body of this Jap yielded other things of importance — a good battle flag, a diary, a photo album, and twenty perfectly good American dollars. I looked them all over that evening, in the comfortable and secure surroundings of our camp at the mouth of the Tanamboga River, where we soon effected a junction with the main forces pushing south, thereby terminating organized resistance on Guadalcanal. We had bedded down for the night and I had bathed in the fresh water of the river while we still had a little bit of daylight left. I sat on my poncho and tinkered with the little gun until it became dark and the land crabs began to seethe all through the sand floor of the grove, making it difficult indeed to get badly needed rest.

I liked this little weapon at first glance; it was hardly more than a handful for a big man yet it retained the lines of the Luger, lacking the boxlike appearance of the small American automatic pistols. Mechanically it was only a smaller version of the Nambu, having all of the Nambu’s faults — especially did it have the fault of a small trigger guard which did not allow enough room for a large finger to rest with any degree of safety.

In overall length it was much shorter than the Nambu, taking up only six and three-quarters inches in extreme measurement along the barrel and receiver groups. It had a barleycorn front sight, the same as the Nambu, but the rear sight was different, being of the plain “V” type notch with no adjustment. It weighed less than one and one-half pounds and had a barrel length of about three and one-eighth inches.

Six rounds were all that could be crammed into the magazine of the little weapon and the ammunition, as in the case of the weapon itself, was a similar appearing cartridge, made smaller than the 8mm stuff used in the Nambu.

Ordnance friends have since told me that the cartridge gives a muzzle velocity of some 950 foot seconds, and that it has considerable penetrating power. Regrettably, the first weapon of this sort that I saw was the only one which I was ever permitted to examine at close range, and I was never able to shoot it because we never found good ammunition. It would have been fun to plink around Tanamboga at lizards and coconuts with that little gun.

Before we moved out of our beach camp we were visited by a group of souvenir-hunting officers from the Navy, and rumor had it that the sergeant sold the little gun, complete with its natty little belt holster, for $200. According to the story, he didn’t really want the $200 — he had merely asked for two bottles of whiskey or $200. The Navy chap apparently felt that he could do better elsewhere with the booze, because he shelled out the $200 and let the sergeant go thirsty.

It is difficult to believe that the Baby Nambu and the better finished regular Nambus could have been turned out by the same people who later on manufactured so much junk. In 1934 the Japanese brought forth a handgun to disgrace their crudest blacksmith. They called this pistol the Type 94, and wisely issued it to people who did not have great use for a weapon, such as pilots and crew members of aircraft. Some few of them got into the hands of Infantrymen later on; I saw a few in Burma in 1944-5.

The weapon was of awkward appearance, with a profile made ugly by a thick breech and a small, outwardly tapered grip. The guns I saw were very roughly finished, with deep tool marks showing on all surfaces, inside and out. I would not have fired one of them for a price — some of the parts appeared to have been cast from pot-metal. Elements of the trigger mechanism projected from the left hand side of the receiver so that a blow against the receiver wall could cause accidental discharge.

The magazine held six rounds, and it took the standard Japanese 8mm pistol cartridge. The sights were of crude fixed type, seldom having more than a very rough degree of relationship to the axis of the bore. Some of my braver friends who fired the monstrosity told me that it would not hit the side of a barn.

For anyone who might doubt the inability of the Japanese to turn out both good and bad guns, a look at the Baby Nambu and the M-1934 alongside each other is more than enough. One has the polished smoothness of a first class handgun; the other looked like a second rate pipe wrench. Most of the doughboys who recovered M-1934 pistols were bright enough to barter them with some of the souvenir-hungry visitors. A lot of M-1934 pistols have gotten back to this country where, I hope, they will serve as horrible examples of what a handgun should never be.

The Baby Nambu — as far as workmanship is concerned — can continue to serve as a model for our best gunmakers.

(Continue to Part 8)

[…] (Go back to previous chapter) […]