Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Leaders in the Northern Church: Sermons Preached in the Diocese of Durham by the late Joseph Barber Lightfoot, Lord Bishop of Durham (published 1907).

Like unto him was there no king before him, that turned to the Lord with all his heart, and with all his soul, and with all his might.

i Kings xxiii. 25.Kings shall be thy nursing fathers.

Isaiah xlix. 23.

What have been the relations of the Church of God to the kings and rulers of this world in different ages? What has been the influence of those relations on its immediate work and on its permanent well-being? How far has it gained or lost by the support or the opposition of the civil power? What strength, what weakness, what education, what corruptions, can be traced to its alliance or its antagonisms with the State or the chiefs of the State? These are questions of momentous interest at all times, but never more so than at the present season.

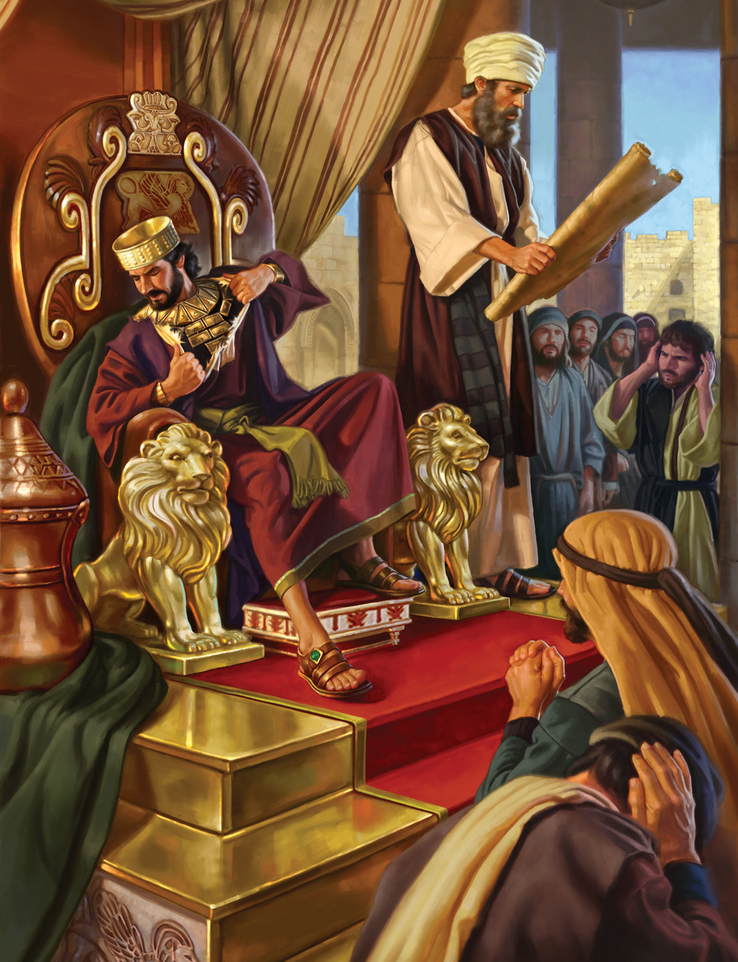

One signal crisis in the history of God’s people, when the alliance between Church and State, between king and priest, was most close, is the reign of that Jewish sovereign whose praises I have just quoted from the record of the Books of Kings. Alike in the reformation of religion and in the disasters which followed, the grasp of the temporal power held the Church tight, so that for good or for evil the destiny of the one was involved in the destiny of the other. David, Hezekiah, Josiah, these three are singled out by the Son of Sirach as alone not defective in the long list of Jewish kings. All the rest “forsook the law of the Most High.” But of the three thus excepted Josiah was the most steadfast, the most earnest, the most courageous champion of religion and protector of the Church.

The Old Testament records no more tragic career – as men count tragic – than the history of Josiah. A period of gross and flagrant apostasy has preceded. His grandfather Manasseh and his father Amon take their rank among the basest renegades of the Jewish sovereignty. Manasseh indeed repents, but Amon dies impenitent. “Amon,” we are told, “trespassed more and more.” Idolatry was rampant everywhere. The worship of Baal and Ashtoreth, of Chemosh and Milcom, all the cruelties and all the profligacies which accompanied the foul rites of the gods of the heathen, ran riot in the land. Amon was murdered by his subjects. Josiah, then a young child, succeeded to this inheritance of corruption and disorder. At once everything is changed. The young king “walked in all the ways of David his father, and turned not aside to the right hand or to the left.” The book of the law was rediscovered. The covenant with God was renewed. The land was swept clean of its idolatry and its abominations clean “as a man wipeth a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down.” The restoration of religion culminated in a great celebration of the chief national and religious festival, a celebration which was renowned through after-ages. “There was not holden such a passover from the days of the judges that judged Israel, nor in all the days of the kings of Israel, nor of the kings of Judah.” What testimony more complete could we desire to the fervour, the devotion, the severe conscientiousness of this king, whose fidelity to the God of Abraham gilded the eventide of the kingdom with a parting glory, ere it set in darkness? Might not the sacred chronicler with justice record that “like unto him was there no king before him… neither after him arose there any like him?”

Yet the next recorded incident is that he was cut off prematurely, cut off suddenly, cut off in his mid-career of pious service to Jehovah, cut off by a heathen king at the head of a heathen host. This was the beginning of the end. When Josiah was lost, all was lost. Therefore we are told “All Judah and Jerusalem mourned for Josiah.” The mourning of Hadad-rimmon became henceforth the type and proverb of a great national grief. Megiddo was a household word for a mighty overthrow. Where else should the Apocalyptic seer place the great and final conflict, when the powers of Satan should muster against the armies of the Lord, but in this great scene of conflict and agony, in Armageddon, the “Hill of Megiddo”? For many generations the day of Josiah’s death was kept as a day of mourning by the nation. “All the singing men and the singing women spake of Josiah in their lamentations to this day, and made them an ordinance in Israel.” Had not the men of that generation just cause to complain that the fathers had eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth were set on edge? Manasseh and Amon had sown the wind, and Josiah must reap the whirlwind.

Analogies have not unnaturally been sought to the person and history of Josiah in sovereigns of later ages. The reign of our sixth Edward lent itself easily to such an application. The youth of the king, the reformation of religion, these two facts combined were enough to suggest the parallel. In both cases also the sovereigns came to an untimely end. But here the resemblance ceased. There was only a sharp contrast between the wasting away of the boy-king before he had attained his sixteenth year on a lingering sick-bed, and the mortal wound which carried off the Jewish monarch in the prime of mature age on the battlefield.

A truer parallel might be found in the great Northumbrian king, whose name is borne by this church, and whose memory we are bound this day to celebrate. Listen to these words: “The remembrance of Oswald is sweet as honey in all mouths, and as music in a banquet of wine. He behaved himself uprightly in the conversion of the people, and took away the abominations of idolatry. He directed his heart unto the Lord, and in the time of the ungodly he established the worship of God.” Might we not imagine that we had here the language of Bede or Adamnan describing the hero-saint of Northumbria? Yet the passage which I have quoted is taken word for word from Ecclesiasticus 24, with only the substitution of a name, Oswald for Josiah.

Like the Jewish king, Oswald succeeded to the throne after a period of apostasy. The year immediately preceding was the darkest in the annals of Northumbrian Christendom. The two kings of Northumbria, Osric of Deira and Eanfrid of Bernicia, renounced the faith of Christ, in which they had been brought up. Osric was the cousin, and Eanfrid the brother, of Oswald. Thus Oswald, like Josiah, succeeded to a heritage of apostasy, bequeathed to him by his own blood-relations. In after-ages this dark year was not reckoned by the names of the perfidious sovereigns, but added, so Bede tells us, to the reign of their successor, “Oswald, the man beloved of God.” The apostasy of the Northumbrian kings was not the only calamity which overwhelmed the Church. The Northumbrian prelate Paulinus had deserted his post, and found refuge in the South. “This ill-omened year,” says Bede, “remains to this day hateful to all good men.” The Church was disorganised, desolated, almost pulverised. It seemed as if Christianity would be stamped out in these northern kingdoms.

Like Josiah, Oswald came as a restorer. From the first moment he never hesitated. He took up his position as a Christian, and he consistently, bravely, faithfully maintained it to his last breath, reckless of all consequences to himself. He rebuilt the ruined walls of the spiritual Jerusalem. He re-created the Church of Northumbria; and after a reign of eight short years he left it so strong that it had little or nothing to fear from the powers of this world.

But if Oswald’s career resembled Josiah’s in the heritage to which he succeeded, if the Northumbrian sovereign was the counterpart to the Jewish in the main work of his reign, and in the resolute spirit which animated this work, still more striking is the similarity in the circumstances of their death. Both died at about the same age, the age which has proved fatal to the lives of so many famous men, – the thirty-eighth or thirty-ninth year. Both received their death-wound in battle. Both died in the moment of defeat, leaving the pagans victorious on the field, and bequeathing sorrow to the Church of God, for which they had fought and conquered, had lived and died.

The reign of Oswald, his whole public career so far as we know, eight years in all, begins and ends with a battle. For a just estimate of his motives, his character, and his worth, we have no better preparation than a review of these two scenes of battle.

The scene of the first battle is the neighbourhood of Hexham, under the shelter of the Roman wall, the spot marked in after-ages by the Chapel of S. Oswald. The apostate kings have been slain in battle. Oswald, baptized and educated as a Christian in Scotland, comes to claim his inheritance, comes as the champion of the Church of Christ. He is met by the forces of the British warrior Cadwalla, the ally of the heathen Penda, the Mercian king. The battle is imminent. A wooden cross is hastily constructed; a hole is dug in the ground; the king seizes the cross, and plants it in the earth, holds it with either hand, while the soldiers fill in the soil. Then he cries aloud to his assembled troops, “Let us all fall on our knees, and together supplicate the Lord Omnipotent, the living and the true, that of His mercy He will defend us from a proud and fierce enemy; for He knoweth that we have undertaken a righteous war for the salvation of our race.” He was obeyed. This done, at dawn of day the soldiers advanced against the enemy. Their arms were crowned with victory, and Cadwalla – the hero of forty battles and sixty skirmishes – was slain. The name of the place, Heavenfield, seemed after the event to have had a prophetic import. Once again the visible cross had been the standard of victory. Once again the watchword of the Christian warrior had been Hoc signo vinces; but a purer, nobler, simpler, manlier heart beat in Oswald’s breast than in Constantine’s.

The second battle-field is a pathetic contrast to the first. The enemy here is the heathen king, the Mercian Penda, the old ally of Cadwalla. The scene of battle is called Maserfield, commonly identified with Oswestry – Oswald’s Tree, Oswald’s Cross, as it was designated by the Britons. The pagan was victorious, Oswald was surrounded by the enemy, and slain on the field. His dying words, a prayer for his soldiers, passed into a proverb, “O God, have mercy on their souls, said Oswald falling to the ground.” What wonder that in after-times the grass seemed to grow more green on the spot where he fell, that the very dust gathered from the ground was thought to be endowed with miraculous virtues? The day of his earthly death, the day of his heavenly birth, was August the fifth. Year by year, as the season recurred, the monks of Hexham repaired to the scene of his first battle, there with solemn service to celebrate the anniversary of his last. Thus Oswald’s earliest cross was linked with his latest.

It is the special privilege of a bishop of Durham that he is surrounded on all sides with the memorials of an early Christendom. Just a fortnight ago I took occasion at the millenary festival of the church of Chester-le-Street to speak of the lessons bequeathed to us by the character and destiny of Cuthbert. My work today is a fit sequel to the former task. In the conventional representations of sculpture Cuthbert’s mitred figure bears in his hands Oswald’s crowned head. Oswald’s skull was enclosed in Cuthbert’s coffin. Oswald’s parish church looks across the Wear on Cuthbert’s great cathedral. The same man, William of Carileph, was, I believe, the builder both of the one and of the other. Having then spoken so lately of Cuthbert, how can I do otherwise than speak of Oswald today?

The Church is built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets; but the upper layers of the masonry are the words and works, the lives and deaths, of the saints and martyrs and evangelists and teachers of succeeding ages. The past has much to teach us, if we approach it with reverence. Contempt would only blind our eyes. In many things we see further, much further, than Aidan and Oswald and Cuthbert. Strange, if it were otherwise. But what ground for self-complacency is there here? The dwarf on the giant’s shoulders has a wider range of vision than the giant. Our seat of vantage is a giant Christendom of eighteen centuries. But let us not deceive ourselves. Reverence is not slavery. We may admire the zeal and devotion, the simplicity and the faith, without acquiescing in the ignorance or embracing the superstition, of the past. We have need even when we are scanning the saintliest lives to prove the spirits, that we may choose the good and reject the evil.

What then are the lessons which Oswald has bequeathed to us? What has he done for us, which demands our thanksgiving today? What was there in the character, the life, the work of the man, of permanent value for us all?

1. I would ask you first to consider our obligations to him as the pioneer of the Gospel in these parts. He is the one human agent to whom more than to any other we in these regions owe our Christianity. I spoke of him before, as having re-created the Church of Northumbria. But in the northern of the two Northumbrian kingdoms, the Church can hardly be said to have existed before his time. Bede says distinctly that “no sign of the Christian faith, no church, no altar, had ever been erected throughout the nation of the Bernicians,” before Oswald planted the cross on his first battle-field. Nor was he content with the erection of external symbols. He took immediate steps for the instruction of the people. Not from Rome, but from Iona, he invited his evangelists. He himself related how on the eve of the battle of Heavenfield the saintly founder of Iona, Columba, the apostle of the North, appeared to him in angelic form and shining raiment, bidding him, “Be of good courage and play the man.” Hence it came to pass that the evangelisation of these northern counties flowed almost solely from Celtic, and not Roman sources. In the simple, wise, sympathetic, large-hearted, saintly Aidan, to whom Northumbria owes its conversion, we have an evangelist of the purest and noblest type. Hardly a single incident is recorded of him, which we could wish untrue; and there are very few Christian saints and heroes in any age, of whom so much can be said. I know not how it is that when so many recent churches bear the names of Cuthbert and Oswald and Bede, Aidan has been almost overlooked in our modern dedications. Yet to whom do we owe more than to him? And Oswald gave us Aidan.

2. But secondly; we trace back to Oswald the earliest alliance of Church and State in these parts. In the fullest and best sense Oswald was a “nursing father” to the Church. Oswald and Aidan worked hand in hand together. Aidan preached, and Oswald interpreted. As Moses and Aaron together led the chosen people through the wilderness unto the land of promise, as Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel and Joshua the son of Josedech worked together in repairing the walls of the Holy City and in building the House of God, so Oswald the king and Aidan the bishop laboured with one mind and one soul for the ingathering of the wanderers and the erection of the spiritual temple. It is not my business now to consider under what circumstances the disadvantages may outweigh the advantages of a close alliance between the spiritual and the temporal power. But the ideal at least is an absolute union between the one and the other, so that the kingdom of this world may be the kingdom of Christ. And in those rude ages under sovereigns like Oswald, who can doubt that the spread of the Gospel and the consolidation of the Church gained enormously by the alliance?

3. But again; our thanksgiving is due also for the personal character of the king. Nursing fathers of the Church have not always led the saintliest lives. The character of Constantine will not bear very close inspection. Even rapacity and greed and selfishness may by God’s good providence be used as instruments of religious reform or spiritual advancement. But there is always some loss in such cases. It was said by a famous heathen writer of old that states would then be governed perfectly when kings were philosophers, and philosophers were kings. We may fitly adopt and modify this saying. In the Christian ideal of human society kings should be saints, and saints should be kings. The combination is rare. As we have had kings who were not saints, so also we have had saints on the throne who were not kings. Edward the Confessor and Henry the Sixth were in some sense saints, but they were deficient in kingly qualities. On the other hand, in Alfred of England and S. Louis of France the king and the saint are combined. In this small class of kingly saints and saintly kings Oswald takes his rank. He was every whit a king. In a short reign of eight years he placed Northumbria once more united and organised at the head of the kingdoms of the Heptarchy. He himself became the chosen suzerain of the whole English people. But he was not less a saint. He was profuse in almsgiving; he spent whole hours during the night in prayer. His first and his last recorded public utterances, as we have seen, were prayers. A cross began and a cross ended his reign.

4. And this brings me to speak of the fourth and last lesson which I desire to draw from Oswald’s career. The end of Oswald’s life, like the end of Josiah’s, was an outrage on poetic justice. But God’s ways are not our ways. The defeat and slaughter of men like Josiah and Oswald is a voice from God declaring in emphatic tones to those who have ears to hear that death is not the end of all things; that this life is only the germ of the true life; that the fleeting “now” is as nothing to the never-ending hereafter. What is the momentary death-pang, what is the transient disaster, when brought face to face with eternal being? Their mortal bodies might die; but their work could not die; they themselves could not die. The anniversary of Josiah’s death was celebrated by loud wailing and national lamentation. On the anniversary of Oswald’s death thanks were given to Almighty God “for the gladsome and holy rejoicing of this day” – I am quoting the words of the old collect. Whence this difference? Is it not that Christ’s passion and resurrection have shed a glory over death, as the portal of eternity? Christ brought life and immortality to light. After all was the cross of suffering at Oswestry so unfit a sequel to the cross of self-dedication at Heavenfield?

Lord, teach us this lesson of Oswald’s life, of Oswald’s death; teach us always in joy and in sorrow, in success and in adversity, in victory and in defeat, to bear Thy cross now, that we may wear Thy crown hereafter.

5

Thank you for this!

Glad to hear it was a blessing to you. We will be posting another J. B. Lightfoot sermon next Sunday.