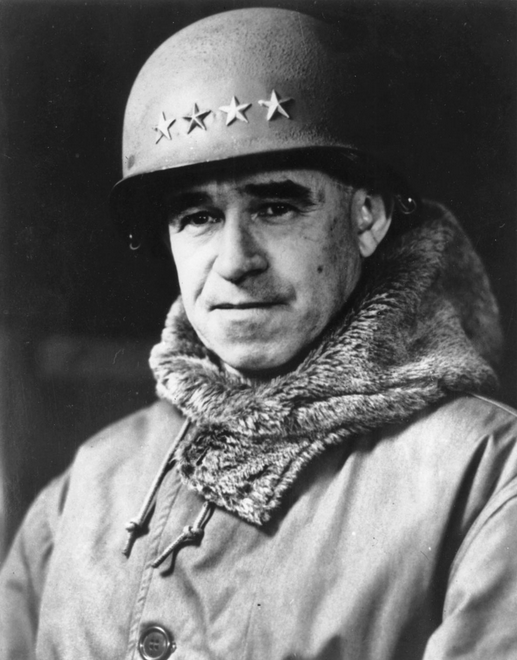

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from General George S. Patton, Jr.: Man Under Mars, by war correspondent James Wellard (published 1946).

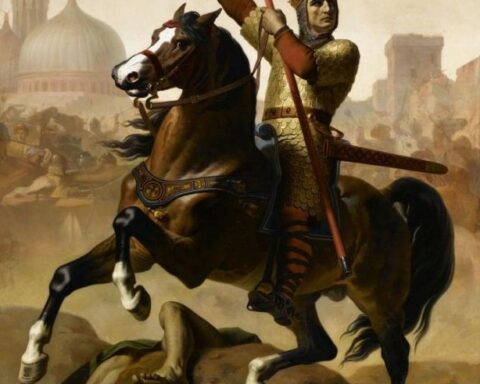

For the Second Front, Patton was given an Army as shiningly splendid to his warlike nature as an electric railway, complete with locomotive, cars, rails, signals, and sidings, to an eight-year-old boy. The Third Army was the Patton Model Army. It raced, roared, and sparkled. It was the 1944 version of a Crusader’s army, with tanks instead of charging horses, radio antennae for flying pennants, helmets for visors. And Berlin was its far Jerusalem.

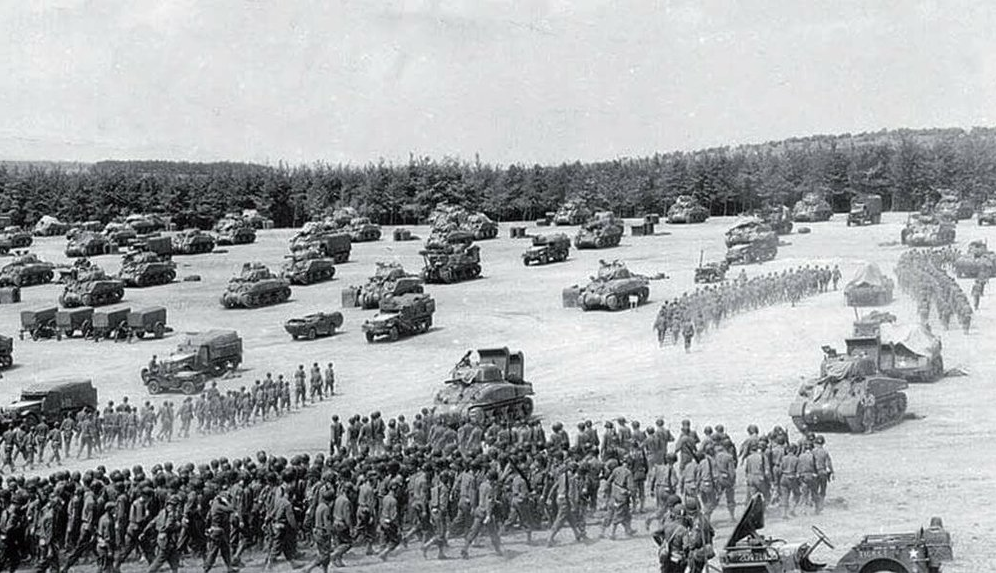

In military terms, the Third Army was a Blitz Army, or a complete army on wheels. Its function was to roll right across Europe; and if Patton could have had his way, to go on rolling right round the earth’s curve, until it was lost in myth, like the Flying Dutchman. A whole army, motorized and steel-skinned, mechanized like no other army in the world; such was the Third Army, which landed on the beaches of Normandy in July, 1944.

George S. Patton was the natural choice of the Allied High Command to lead this spectacular army, for the Third Army was the Allies’ Blitz Army, and Patton was our only Blitz general.

But the actual invasion was never envisaged as a blitz operation. The planners wanted nothing spectacular and unpredictable about it. They didn’t want Light Brigade charges or generals with pearl-handled pistols and an overdeveloped desire for glory getting mixed up with the mechanics of beach parties. The invasion, in brief, was a job of ballistics, not heroics.

It was also a job for a general who husbanded his forces, who preferred to consolidate what he had won instead of pressing on with half a division while the other half was still pinned down on the beaches. In short, the only objective of the first phase of the invasion was to get ashore and stay there, because if we had ever been driven off, the war might have gone on for the rest of our lives.

So Eisenhower skilfully chose General Omar Bradley to command the American invasion forces; and General Sir Bernard Montgomery to command the British.

General Bradley was perhaps the best and the soundest of the Allied field commanders in the formal sense. He belongs, in his training and thinking, to the safe school in American military tradition, and his strategy always had the cleanness and precision of a chronometer. He shows his modest and almost academic character in his appearance. Tall, with a creased, bespectacled face and the parchment like skin of a mule-skinner, he enunciates his views with a nasal timbreless voice, which somehow conveys tremendous confidence to those who hear it. He looks altogether undistinguished, yet distinctly American. When I first met him, as Patton’s second in command in Southern Tunisia, I thought he appeared more like a professor from a mid-western Methodist College than a professional soldier and brilliant strategist. Later, in North Africa, he proved his genius in the campaign which smashed through to the sea at Bizerte parallel with the British First and Eighth Armies on the right which drove into Tunis. This was a victory Patton had not been able to accomplish at Gafsa. Patton had never taken Maknassy or El Guettar. Bradley took Bald and Green Hills, considered impregnable natural fortresses. And he took Mateur and Bizerte.

We correspondents did not see much of Bradley in those days, and though he was always available and held regular press conferences during the European campaign, he was never concerned with publicity for himself, and his personality, like his appearance, was not adapted to newspaper accounts of war. During the final phases of the European War, and particularly during the Ardennes offensive, he became involved, against his whole wishes, with politics; and he appeared in a different light. Bradley was responsible for the Allied reverses in the Ardennes and he admitted it, and explained in his careful and honest way what had happened. But before he could do so, Field Marshal Montgomery had also done some explaining, not so careful and not so honest. And it was then that Bradley, for the first time, became concerned with military politics, and spoke to us like a military politician. I was present at his conference in Luxembourg, on January 9, 1945, when he announced that Montgomery’s command of the American Twenty-first Army Group was temporary only. I know Bradley was angry and bitter over what had happened, especially over Montgomery’s tactless claims and extravagant statements about stopping von Rundstedt, but he faced the occasion in his usual dry, honest, Missourian way, and all of us, including the British correspondents serving with American armies, sympathized with him.

Bradley’s genius was different from Patton’s in all ways. Bradley was solid and American. Patton was American but not solid. Bradley won his victories — and they were as conclusive as Patton’s — with his mind; Patton won his by his personality. Bradley loved his soldiers for what they were — American civilians in uniform. He cherished and husbanded them. Patton loved his soldiers for what they came to be — fighting men in battle units. I don’t think he cherished or husbanded them. Conversely, American soldiers loved Bradley. Bradley had an immense following in the American army, and the disturbing, even dangerous aspect of the Bradley-Montgomery dispute over the Ardennes was Montgomery’s implied disrespect for Bradley, the favorite general of the American troops. For in Bradley’s First and Ninth Armies were many veterans of the North African and Sicilian campaigns, and these men believed in Bradley, not Montgomery. I never met an American soldier who loved Patton in this way. I have told how, when Patton took command of the 2nd Corps in Tunisia, our soldiers hated him. They hated him bitterly after Sicily, and it was this hate which nearly ended his career as a general, because what General Eisenhower and the War Department were really concerned with, was the morale of our troops under a leader the fighting men hated.

Bradley had his genius, and this again was different from Patton’s. Bradley’s genius was strategic, Patton’s more tactical. Bradley, as Commander-in-Chief of the American army groups in the field, was responsible for drawing the large arrows on the map which later became the Patton, Hodges, and Simpson drives.

General Bradley, then, was the natural and proper choice for the commander of the American invasion forces. We remember that this was the biggest and most responsible job ever given to an American soldier. And we remember that it was accomplished successfully.

From General Eisenhower’s point of view, thinking of the British generals, Montgomery was the natural and proper commander to lead the British into Europe. In June, 1944, Montgomery was the most successful of the Allied soldiers, not only in terms of accomplishments, but in the important sense of personality. In modern war, a general’s personality is as important as his genius, because newspapers condition the way wars are run and their ultimate results. Newspapers, in turn, require colorful personalities to make readers read about war and like the way the war is being run; hence the success of generals like Montgomery and Patton and MacArthur, whose military genius is actually obscured in the vividness of their newspaper personalities.

Field Marshal Montgomery was such a vivid personality to the English newspapers; and they began, methodically, after the end of the Desert and Tunisian campaigns to groom him into the victorious Second Front general. Montgomery cooperated patriotically and eagerly, and really was what the newspapers intended him to be, which was a religious, crusading man who ardently believed in God and victory. To those of us who knew Montgomery at close quarters over four years of war, this ardor became wearisome; and we had a sense of irritation over the difficulty of discovering whether Monty was actually a good general or merely a good military politician. I did my best to formulate at least a personal opinion, and I concluded that he was a safe if not brilliant general, with a degree of military cunning which sometimes is as good as brilliance. At any rate he was a field commander and a soldier, and from him radiated the light of professional soldiering, so that his subordinate commanders, and under them the field officers, and, in turn, the fighting men or British Tommies, were professional and safe.

These two Allied commanders, then — Generals Bradley and Montgomery — were the wise choice of General Eisenhower and our war counselors to undertake the invasion of Europe. Their genius, experience, and personalities were requisite; neither was reckless nor unpredictable.

But the Allied High Command calculated that, in addition to the necessary weight for a successful landfall on the beaches of France, our war potential was now so tremendous that the time had come when we could afford spare armies and unformalistic generals like Patton. Thus the Third U. S. Army was conceived almost as an extravaganza of modern war; and thus it was given to our most extravagant general to command. Patton was the type to do unpredictable and logically unmilitary things. He was likely to do things which were confusing to us. How much more confusing would they be to the enemy!

In the beginning of the invasion of Europe there was simply no room for another army in the rectangle of coast-land we held in Normandy. It was, therefore, a month before Patton’s army embarked and landed, without having to fire a shot or wet their feet on Utah Beach, July 6, 1944.

We of the Third Army crossed the channel in the largest convoy I had seen since D Day. The lines of Liberty ships were so long and spread so far out over the sea that we could not see our escorting warships. We reached France in the evening, and were appropriately welcomed to Normandy beaches by a summer storm. We lay off Utah Beach until morning, when the LCTs came out to ferry men and cargo to the sandy beach. I was struck by the casual stage the war had already reached after only a month. The front lines were some twenty miles from the beaches where we were landing, but there were no signs of battle. The LCT serving our Liberty ship Dan Beard was called the Stork Club and was skippered by Ensign Billingsley of the New York night club. Billingsley and his odd craft typified the atmosphere on Utah Beach on that morning of July 7. The ensign — tanned, easy, and casual — bumped the Stork Club into the Dan Beard, and the crew of neither ship seemed fired with zeal to make the LCT fast, and thereby to proceed with the job of landing the Third Army and getting on with the war. Well, it was a fine summer morning, and these men were all veterans of the D-Day and subsequent landings, and the certain mark of the veteran is his easy and casual way in the face of great events. So, as the passengers waited anxiously to set foot in France, the Stork Club bumped against the Dan Beard, ropes trailed in the water, and the latrine from the big Liberty ship poured over the side into the small LCT. The Third Army’s arrival in Europe was no more romantic than this.