Two decades before America’s ordeal in Vietnam, the Netherlands waged its own doomed Southeast Asian war in the vast archipelago of the Dutch East Indies. This conflict, the Indonesian War of Independence, lasted from August 1945 to December 1949. It marked the end of three centuries of Dutch colonialism in the Far East and the rise of a new country, the Republic of Indonesia.

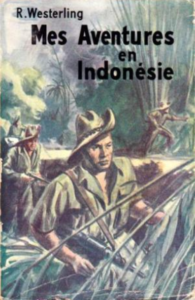

Of all the Dutch soldiers who fought there, none proved more ruthlessly effective at suppressing enemy guerilla activity than Capt. Raymond “Turk” Westerling. Indonesians have branded him a war criminal. In Holland he has always been omstreden (controversial). What Westerling thought of himself and his actions he expressed in his 1952 memoir, published in French as Mes Aventures en Indonésie. The English translation of this work, Challenge to Terror, gives Anglosphere readers a fascinating and sometimes disturbing glimpse into a little known corner of military history.

Raymond Paul Pierre Westerling begins his story in Istanbul, where in 1919 he was born to a Greek mother and a Dutch father. He recounts an intrepid boyhood wherein he defied repeated paternal spankings to make daylong solitary excursions into the nearby high country. In these mountains he became acquainted with the Turkish peasants, learned to appreciate their folkways, and thus acquired a lifelong sympathy for rural Asiatics. Initially he was educated at home by tutors, but his parents later enrolled him in a private school where he excelled academically (with minimal effort, he adds). At school Westerling gathered some friends about him, shared his modest allowance money, and inflicted justice on bullies. It pleased him greatly to play the role of a magnanimous benefactor and fighting hero. To these exploits he added a near-disastrous experiment with gunpowder that, at age 13, nearly cost him his eyesight.

Auspicious youth gave way to the drab adulthood of a retail cashier job. He then found more interesting employment in a ship chandler shop, where tales told by world-traveling mariners fired his imagination. The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 offered a dazzling prospect of foreign adventure that proved irresistible. In 1941, he went to the Netherlands embassy and enlisted in the Dutch Army to fight the Nazis.

Holland by that time lay under German occupation, so Westerling embarked on a long, circuitous sea voyage to join Dutch forces mustering in exile. During stops in Africa he visited Bedouins, became engaged (only to jilt the bride when he was ordered to reembark), and provoked a mob of irate Zulus. Arriving at last in Canada for basic training, he rapidly became fluent in Dutch – a language until then unfamiliar to him – and showed himself as adept at soldiering as he had been at study.

He then transferred to Britain, where he received paratrooper and commando training. In this part of the story Westerling outlines some of the techniques of unconventional warfare, and reflects uneasily that what makes a man a proficient commando can also make him an arch criminal. Frustratingly, he mastered these specialized skills (including a course in jungle warfare training in Ceylon) only to be repeatedly passed over for combat missions and relegated to the instructor role.

Finally deployed to the front line in continental Europe after D-Day, he was ordered to avoid engaging the Germans. He partly evaded this restriction by taking men behind German lines for “operational training” forays, but these sorties were not assaults. Following Germany’s defeat, and seeing victory over Japan approaching, Westerling all but resigned himself to disappointed hopes and a lackluster military career. But his fortunes were about to change dramatically.

For whereas Germany’s surrender in May 1945 ended war in the Netherlands, Japan’s formal capitulation in August ignited a violent revolution in the Dutch East Indies. Indonesian nationalists, led by Sukarno, had proclaimed independence and begun fighting to prevent reimposition of European rule (the old colonial system having been destroyed by the invading Japanese in 1942). The bulk of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army were ragged ex-POWs scattered in prison camps across the former Japanese Empire. Most of the civilian Dutch colonists languished in concentration camps, sick, starving, and at the mercy of vengeful natives. The British military, nominally in charge of the East Indies as part of their South East Asia Command, lacked sufficient troops to impose order. Worse, the British refused to permit the landing of any Dutch forces for fear that this would escalate hostilities beyond their control. Much reliance was placed on the Japanese occupation garrisons, still in place and heavily armed. Charged with protecting the civilians they had formerly brutalized, the Japanese in practice did as little as possible to resist the revolutionaries, when they didn’t positively abet them. Anarchy and terror spread, flaring most savagely on the islands of Java and Sumatra.

Any Dutch soldier permitted to do his duty in this theater could succeed only through exceptional intelligence, flexibility, and aggression. Here was work fit for a commando, urgent enough that Westerling’s superiors finally decided to commit him to the adventure he had always sought. In September he parachuted into Medan, principal city of Sumatra, with a small staff and a daunting mission: establish a police force in the midst of lawlessness to prepare the way for incoming Allied troops.

Westerling found Medan to be a city ravaged by unrestrained banditry, rape, and murder. He enlisted a modest number of pro-Dutch Indonesians to help restore the peace, but the local Japanese commanders refused to arm them. Instead they were permitting guerillas to help themselves to truckloads of weapons from Japanese armories. Westerling and his men simply hijacked some of these rebel trucks to obtain guns for the new police force. The problem of protecting European civilians was more difficult, and not at all helped by the blundering of several minor colonial officials whose insistence on “showing the flag” only invited attack. The fate of some other Europeans during this time, in particular a Swiss family that befriended Westerling, makes for grim reading. The most grievous blow was the disappearance of a young woman he loved. Westerling presumes the guerillas kidnapped and killed her in some unspeakable manner.

After the British landed in force and Medan was made more secure, Westerling began counterinsurgency operations in northern Sumatra. He quickly grasped the essentials of Indonesian psychology, and his rapport with inhabitants of the kampongs – the rural villages – owed much to his familiarity with Islam (he had memorized many suras from the Koran). To his native allies he was that most unusual type of European, the one who knows how to humble himself in respect of their culture without diminishing in their eyes the authority of the higher civilization he represents.

__________________________________________________________

I did not approach them as a superior being who looked down upon them and intended to mete out justice to them, as I saw it, from above. I met them on their own level and I took the trouble to learn their customs and way of life.

When I entered a native cabin, if they brought me a chair, while the Indonesians sat on the floor, I refused it and took my place on the floor with them. I understood the meaning of the difference. Indonesian society is built upon a pyramid of castes hardly less complicated than that of India. The tani, the peasant, must always sit on a lower level than the warriors, the nobles or the intellectuals. By offering me a chair, they were showing a willingness to accept my superiority. By refusing it, I renounced the claim to superiority and made myself one with them. It was a gesture of fraternity which touched them deeply. It made them at once my friends and my allies.

By the same token, when a native came to my office to make a complaint or to ask for help, I always gave him a chair – which the officials of the Republican government claiming to represent the people of Indonesia would never have done. Conversely, when a terrorist came to submit to my authority or to confess his crimes, I made him crawl on his knees to my desk. It was what he expected. If I had received him otherwise, he would have deduced from my incomprehensible lenity that he was not in disfavour in spite of his crimes and that he might therefore commit others with impunity.

I made it a rule also never to refuse help to any native who came to ask it of me. If a father came to me to ask me to try to recover his daughter, carried away by bandits – it was the most common case in which my assistance was sought – even though I was alone, even though I or my men might be overcome with fatigue, I always made an effort, too often alas, in vain, to save the victim. I never dismissed a native who came to me with a complaint, even though it might be against one of my own soldiers. I always listened attentively and fraternally, and if redress was justified, the plaintiff received it. When I made a promise to a native, I always kept it, however much I may have wished later that I had not committed myself. Finally, the detail in which my technique differed perhaps most startlingly from that of certain of my colleagues was that I did not gives whites priority over natives. In some places, if a white entered an Allied office while a native was there, that native’s business was immediately adjourned until the white had been attended to. But if a white entered my office while I was talking to a native, I asked him to wait until my Indonesian brother had finished with his business. The Indonesians marvelled at this. For that matter, so did the whites, if that is quite the word for it.

__________________________________________________________

To his enemies, Westerling and his men were fearsome spirits of the dark — tracking and ambushing insurgents with a speed and cunning that surpassed their own, aided by an excellent network of native spies he’d recruited. An early trophy of these hunts was the Terakan, an especially notorious guerilla chieftain whom Westerling seized after a British major wagered a bottle of Scotch that it couldn’t be done. The Dutch captain’s exemplary public display of the Terakan’s severed head left no doubt that he would meet cruelty with cruelty.

The success in the Medan area was followed by his transfer to Java, where, in June 1946, he began instructing other Dutch commandos in his methods of warfare. First he weeded out all but the toughest volunteers, wanting only men who were willing to push themselves to the utmost limits of bravery and endurance.

__________________________________________________________

“I began by lecturing my troop on the principle which was to be the basis of the type of training we would undergo and of the operations to follow it. It was that we were not faced by a hostile population – far from it. Our basic assumption was that we were working on behalf of a friendly population, as anxious to be freed from the terrorism of the bandits as we ourselves were anxious to end their depredations. It was among the population that we would find our most valuable supporters. It would be they who would be our best informers, for they could move about unsuspected where a white man would be immediately conspicuous, and it was they who knew intimately the terrain, an indispensable condition to the success of our enterprise.

Since our enemies were the bandits alone and not the population some of them claimed to represent, we must never fire a village or burn the hut of an innocent native. We would attack only the leaders of the bands and armed guerillas. These bandits, these pseudo-soldiers had terrorized the people of the kampongs, and for that matter those of the cities. At first, the local people might be afraid to help us. But as they saw that we attacked only their oppressors, and never themselves, we would win their confidence and, particularly if we showed ourselves capable of protecting them against the bandits, we would eventually received precious aid from them.

Even in the Republican “soldiers”, the bandits and gangsters with whom we had to deal, I continued, we should not necessarily see enemies. Many of their followers were misled. Many of them, inspired by a sincere desire for independence, had allowed themselves to be made the tools of the terrorists in the belief that by so doing they were serving the ends of national independence, even though the means used might be personally repugnant to them. Some of them might have been sucked into these bands and obliged to remain with them through fear of reprisals if they attempted to get out. Joining a terrorist band was, after all, one way of escaping attack by the terrorists. We would find in these bands, I said, individuals who could be redeemed and converted from destroyers of order into supporters of it. Indeed, later on, I very often appointed former terrorists (not their leaders of course) as the official police of villages which they had once looted, with excellent results.

It was the bandit leaders alone against whom we were declaring implacable war, I concluded. The way to seize them was to make ourselves men of the jungle. Always surprise, ambush, ruse, never frontal attacks. We would never operate by day. (As a matter of fact, during three years, I never started an action by daylight). We would be the soldiers of the night, taking our enemies by surprise in the dark. We would thus be aided by the powerful psychological factor of the terror Indonesians have for the dark.”

__________________________________________________________

At the end of November, he received orders to proceed to the island of Celebes, now called Sulawesi. It was here particularly, in South Celebes, that he has been accused of committing atrocities. Westerling tells a different tale, asserting that the villagers of Celebes did not sympathize with the guerillas, and that he found much cooperation and friendship among them. He does admit to a judicious brutality, e.g., personally gunning down an Indonesian in the middle of the Makassar Society Club (Westerling claims he was a spy, whom he’d already given fair warning to clear out), and the staging of a mock execution to frighten villagers into revealing the identities of guerillas among them. But he also describes milder methods of psychological warfare which proved highly effective. He refuses to accept responsibility for excesses committed by units not under his command. When he left Celebes in February 1947, Dutch forces had virtually eradicated the insurgency there.

Westerling frequently digresses from his war adventures to give his views of the strategic picture in Indonesia and the high-level political machinations on both sides. He stresses that the archipelago is not a single nation but a collection of diverse peoples (Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, Batak, Toraja, Papuans, etc.). He fervently endorses the Dutch government’s post-colonial plan for a multi-ethnic, federal United States of Indonesia. To this scheme he contrasts the centralizing ambitions of the Republic, a Javanese enterprise bent on complete hegemony over all the islands. Westerling’s opinion of Sukarno and the other Javanese revolutionary leaders is entirely negative: he denounces them as incorrigible terrorists unfit for political power. His estimation of the Dutch government is far kinder, but he charges its ministers and negotiators with pusillanimity and willful ignorance of Indonesian realities. As a combat officer, he could only watch in frustration as the politicians traded substantial concessions for empty Republican promises, nullifying victories won by the military. He shows how they labored under immense pressure from the mass media, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Nations – the same censuring chorus of “world opinion” that would later hound whites out of power in Rhodesia and South Africa. Yet he does not acknowledge the prohibitive expense of Holland’s “debt of honor” owed to a chimerical Indonesian federation. The Dutch had grown terminally weary of war and empire.

In late 1948 General Spoor, the supreme Dutch Army commander in Indonesia, summoned Capt. Westerling and told him to prepare his men for an undisclosed but highly important mission. Westerling soon learned that the mission objective was to capture the top leaders of the Republic. He asked the general if he could guarantee that these men would be put on trial, not meekly turned loose again to appease the inevitable outrage of the UN. Spoor replied that he could make no such promise, whereupon Westerling resigned from the military.

Now a civilian, he observed from a distance the predictable charade of Sukarno’s arrest, comfortable incarceration, and inevitable release. No matter, for he contented himself with marriage, starting a family, and founding a business. Like so many Dutchmen who’d fought in the East Indies, he had come to feel at home there and planned to remain through the coming winds of political transformation. The Dutch progressively drew down their forces.

On December 27, 1949, the Netherlands officially transferred sovereignty to the shaky edifice of the United States of Indonesia. Sukarno’s lieutenants wasted no time in dismissing or imprisoning the powerless figureheads of the federation. There was to be only one Indonesia, the unitary Republic.

Westerling’s last adventure in Indonesia is the strangest and most difficult to fathom. Prudently, he had chosen to live among the Sundanese people of West Java, not among the Javanese, who had once put a bounty on him. If his account can be believed, the Sundanese came to regard him as their sole protector. More than this, he claims his followers believed him to be Ratu Adil (Prince Justice, i.e., the Just Ruler), a messianic deliverer foretold in the Joyoboyo Prophecies. On the strength of their devotion he raised and trained a private army called the Legion of Ratu Adil (APRA), ostensibly a defensive militia.

In January 1950, Westerling launched a coup d’etat against the fledgling Indonesian government. His soldiers in Bandung defeated the Siliwangi Division (the Republic’s best troops) and took control of the city. The coup fizzled when the force he led personally, tasked with seizing Jakarta, failed to receive an expected shipment of weapons. Having prepared for exfiltration like any properly trained commando, Westerling slipped out of Java, spent jail time in Singapore while the Indonesians tried vainly to extradite him, and finally made his way to Europe.

But assuming the APRA coup had succeeded, what then? How could one Dutchman backed by a tribal militia have ruled the East Indies? The author denies any grand dictatorial plans, averring only a desire for the safety of the Sundanese state of Pasundan. Yet his was a counterrevolution with no ultimate goal — if not a deluded act of pure hubris, then at best the gambit of an expert tactician who had never directed major strategic operations.

The memoir’s final chapter assesses the state of Indonesia in 1952, which, to Westerling’s mind, is dire. He sees a country of seventy-five millions tyrannized, ill-governed, and in peril of communist takeover. History shows this last concern was not merely Cold War paranoia. The Red coup attempt that he foresaw did take place in 1965, provoking reprisal massacres by the Indonesian Army that, combined, rank as one of the great mass murder campaigns of the 20th century.

Westerling concludes by professing affection for the people of Indonesia, albeit with a slightly sinister edge:

__________________________________________________________

The Indonesians have a right to independence, as I have said. But that means all of them. Not only those of Central Java, whose domination over the other islands has been so cruelly exercised both in ancient history and in the last few years. The Indonesians of every island, of every religion, of every race. Their independence, within an Indonesian Union, is the dream of all those populations so brutally conquered in 1950 by the government of Djakarta.

If I ever return to Indonesia, it will be to serve that ideal of independence. It will be to aid the genuine democrats who seek to end the armed tyranny which now oppresses them in order to establish at last a régime based upon free popular elections. For did you know that the Indonesian people, in whose name Sukarno and Company profess to speak, have never yet been called upon to vote in a general election?

But if Indonesians have never had a chance to express by vote how they feel about the cause I espoused or how they feel about me, they have managed to do that without voting. They gave me spontaneously the title which pleases me more than any other honour which has come my way, more than the eight campaign ribbons I may wear, more than the four recommendations for the highest military decoration. It is a title not often accorded to a man of thirty-one.

My friends the tanis called me Bapa. It means father.

And my friends the tanis are still waiting for the coming of Ratu Adil, Prince Justice, announced by their prophet – the deliverer born in Turkey. They saluted me by that name once. But I failed to deliver them….

__________________________________________________________

Proverbs 18:17 tells us, “The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him.” The foregoing review presumes neither to exonerate nor condemn Raymond Westerling. Yet this reviewer has lived in Indonesia, and can attest that certain of the author’s observations about those islands ring true. The book may disappoint readers expecting an action-packed military account with many detailed descriptions of firefights, but it will reward those curious about the history of the great tropical archipelago. If today Indonesia draws global attention chiefly when natural disasters strike (it is the most volcanic region on Earth), that country’s human upheavals are at least equally worthy of interest.

5

Well this was really cool. Never even heard of this war, just assumed post colonial retreat after wwii. Thanks for another enlightening read Mr. Mantel.

Glad you found it interesting. Most Western accounts of this war are written in Dutch, so it was a great pleasure to find a translated work to review.

5