Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, by Charles Morris (published 1896).

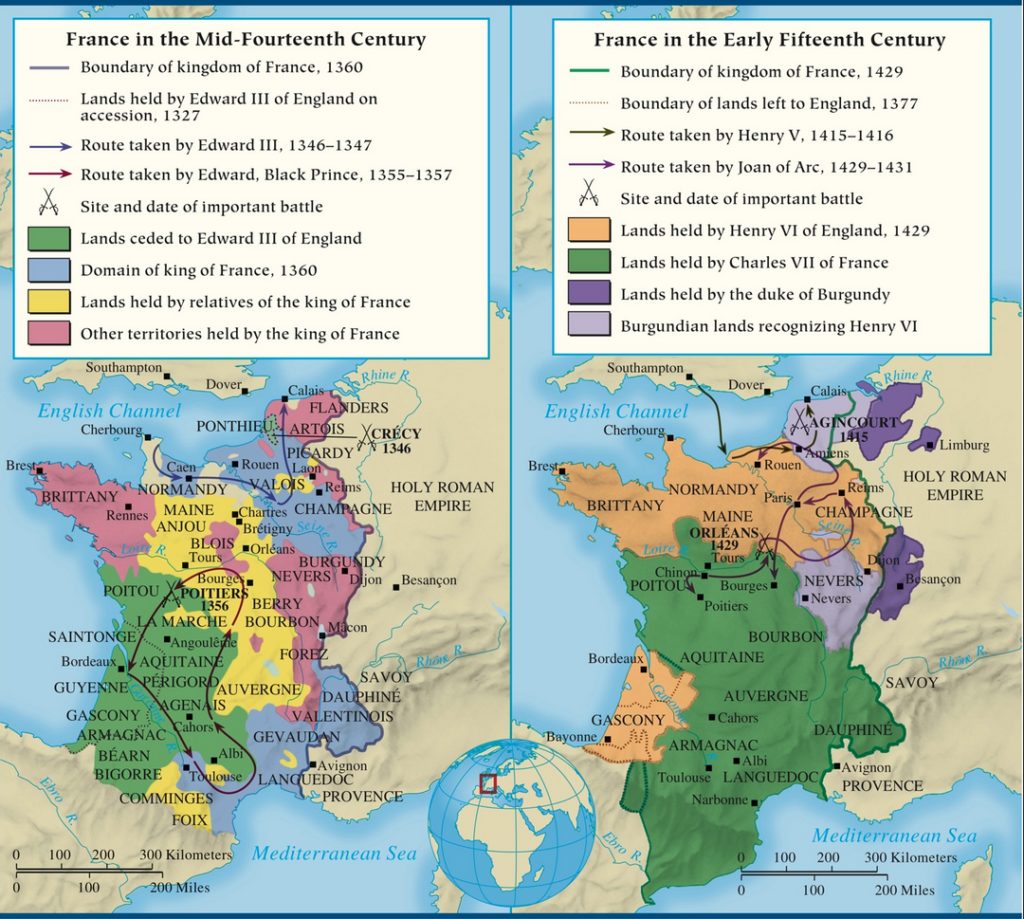

It was in the heart of the Hundred Years’ War. Everywhere France lay desolate under the feet of the English invaders. Never had land been more torn and rent, and never with less right and justice. Like a flock of vultures the English descended upon the fair realm of France, ravaging as they went, leaving ruin behind their footsteps, marching hither and thither at will, now victorious, now beaten, yet ever plundering, ever desolating. Wherever they came the rich were ruined, the poor were starved, want and misery stared each other in the face, happy homes became gaping ruins, fertile fields became sterile wastes. It was a pandemonium of war, a frightful orgy of military license, a scene to make the angels weep and demons rejoice over the cruelty of man.

In the history of this dreadful business we find little to show what part the peasantry took in the affair, beyond that of mere suffering. The man-at-arms lorded it in France; the peasant endured.

Yet occasionally this down-trodden sufferer took arms against his oppressors, and contemporary chronicles give us some interesting insight into brave deeds done by the tiller of the soil. One of these we propose to tell, a stirring and romantic one. It is half legendary, perhaps, yet there is reason to believe that it is in the main true, and it paints a vivid picture of those days of blood and violence which is well worthy of reproduction.

In 1358 the king of Navarre, who had aided the English in their raids, suddenly made peace with France. This displeased his English allies, who none the less, however, continued their destructive raids, small parties marching hither and thither, now victorious, now vanquished, an interminable series of minor encounters taking the place of large operations. Both armies were reduced to guerilla bands, who fought as they met, and lived meanwhile on the land and its inhabitants. The battle of Poitiers had been recently fought, the king of France was a prisoner, there was no organization, no central power, in the realm, and wherever possible the population took arms and fought in their own defence, seeking some little relief from the evils of anarchy.

The scene of the story we propose to tell is a small stronghold called Longueil, not far from Compiègne and near the banks of the Oise. It was pretty well fortified, and likely to prove a point of danger to the district if the enemy should seize it and make it a centre of their plundering raids. There were no soldiers to guard it, and the peasants of the vicinity, Jacques Bonhomme (Jack Goodfellow) as they were called, undertook its defence. This was no unauthorized action. The lord-regent of France and the abbot of the monastery of St. Corneille-de-Compiègne, near by, gave them permission, glad, doubtless, to have even their poor aid, in the absence of trained soldiery.

In consequence, a number of the neighboring tillers of the soil garrisoned the place, providing themselves with arms and provisions, and promising the regent to defend the town until death. Hither came many of the villagers for security, continuing the labors which yielded them a poor livelihood, but making Longueil their stronghold of defence. In all there were some two hundred of them, their chosen captain being a tall, finely-formed man, named William a-Larks (aux Alouettes). For servant, this captain had a gigantic peasant, a fellow of great stature, marvellous strength, and undaunted boldness, and withal of extreme modesty. He bore the name of Big Ferré.

This action of the peasants called the attention of the English to the place, and roused in them a desire to possess it. Jacques Bonhomme was held by them in utter contempt, and the peasant garrison simply brought to their notice the advantage of the place as a well-fortified centre of operations. That these poor dirt delvers could hold their own against trained warriors seemed a matter not worth a second thought.

“Let us drive the base-born rogues from the town and take possession of it,” said they. “It will be a trifle to do it, and the place will serve us well.”

Such seemed the case. The peasants, unused to war and lacking all military training, streamed in and out at pleasure, leaving the gates wide open, and taking no precautions against the enemy. Suddenly, to their surprise and alarm, they saw a strong body of armed men entering the open gates and marching boldly into the court-yard of the stronghold, the heedless garrison gazing with gaping eyes at them from the windows and the inner courts. It was a body of English men-at-arms, two hundred strong, who had taken the unguarded fortress by surprise.

Down came the captain, William a-Larks, to whose negligence this surprise was due, and made a bold and fierce assault on the invaders, supported by a body of his men. But the English forced their way inward, pushed back the defenders, surrounded the captain, and quickly struck him to the earth with a mortal wound. Defence seemed hopeless. The assailants had gained the gates and the outer court, dispersed the first party of defenders, killed their captain, and were pushing their way with shouts of triumph into the stronghold within. The main body of the peasants were in the inner court, Big Ferré at their head, but it was beyond reason to suppose that they could stand against this compact and well-armed body of invaders.

Yet they had promised the regent to hold the place until death, and they meant it.

“It is death fighting or death yielding,” they said. “These men will slay us without mercy; let us sell them our lives at a dear price.”

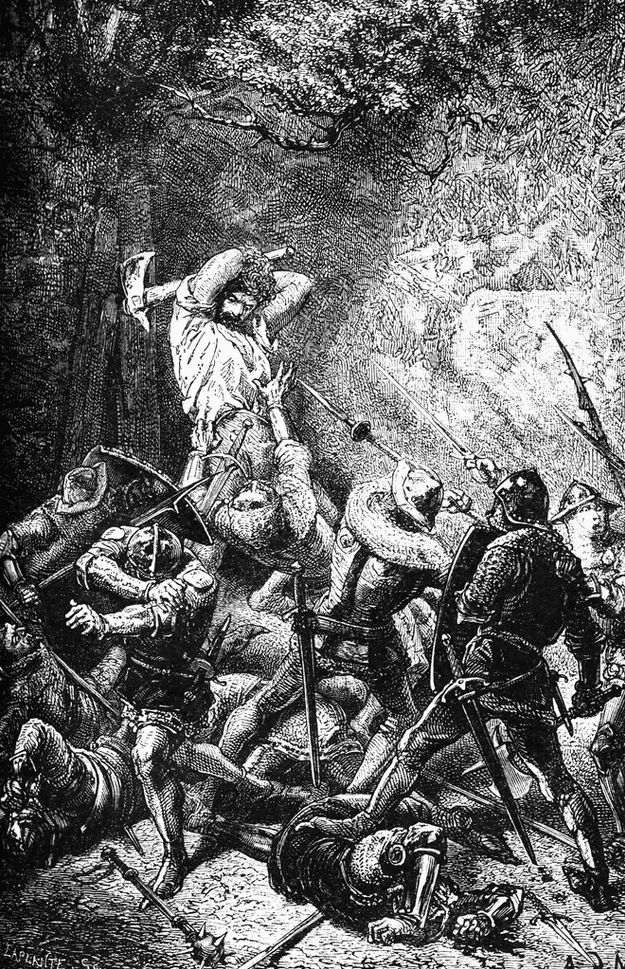

“Gathering themselves discreetly together,” says the chronicler, “they went down by different gates, and struck out with mighty blows at the English, as if they had been beating out their corn on the threshing-floor; their arms went up and down again, and every blow dealt out a mighty wound.”

Big Ferré led a party of the defenders against the main body of the English, pushing his way into the outer court where the captain had fallen. When he saw his master stretched bleeding and dying on the ground, the faithful fellow gave vent to a bitter cry, and rushed with the rage of a lion upon the foe, wielding a great axe like a feather in his hands.

The English looked with surprise and alarm on this huge fellow, who topped them all in height by a head and shoulders, and who came forward like a maddened bull, uttering short, hoarse cries of rage, while the heavy axe quivered in his vigorous grasp. In a moment he was upon them, striking such quick and deadly blows that the place before him was soon void of living men. Of one man the head was crushed; of another the arm was lopped off; a third was hurled back with a gaping wound. His comrades, seeing the havoc he was making, were filled with ardor, and seconded him well, pressing on the dismayed English and forcing them bodily back. In an hour, says the chronicler, the vigorous fellow had slain with his own hand eighteen of the foe, without counting the wounded.

This was more than flesh and blood could bear. The English turned to fly; some leaped in terror into the ditches, others sought to regain the gates; after them rushed Big Ferré, still full of the rage of battle. Reaching the point where the English had planted their flag, he killed the bearer, seized the standard, and bade one of his followers to go and fling it into the ditch, at a point where the wall was not yet finished.

“I cannot,” said the man; “there are still too many English there.”

“Follow me with the flag,” said Big Ferré.

Like a woodman making a lane through a thicket, the burly champion cleared an avenue through the ranks of the foe, and enabled his follower to hurl the flag into the ditch. Then, turning back, he made such havoc among the English who still remained within the wall, that all who were able fled in terror from his deadly axe. In a short time the place was cleared and the gates closed, the English—such of them as were left—making their way with all haste from that fatal place. Of those who had come, the greater part never went back. It is said that the axe of Big Ferré alone laid more than forty of them low in death. In this number the chronicler may have exaggerated, but the story as a whole is probably true.

The sequel to this exploit of the giant champion is no less interesting. The huge fellow whom steel could not kill was slain by water,—not by drowning, however, but by drinking. And this is how it came to pass.

The story of the doings at Longueil filled the English with shame and anger. When the bleeding and exhausted fugitives came back and reported the fate of their fellows, indignation and desire for revenge animated all the English in the vicinity. On the following day they gathered from all the camps in the neighborhood and marched in force on Longueil, bent on making the peasants pay dearly for the slaughter of their comrades.

This time they found entrance not so easy. The gates were closed, the walls well manned. Big Ferré was now the captain of Longueil, and so little did he or his followers fear the assaults of their foes, that they sallied out boldly upon them, their captain in the lead with his mighty axe.

Fierce was the fray that followed. The peasants fought like tigers, their leader like a lion. The English were broken, slaughtered, driven like sheep before the burly champion and his bold followers. Many were slain or sorely wounded. Numbers were taken, among them some of the English nobles. The remainder fled in a panic, not able to stand against that vigorous arm and deadly axe, and the fierce courage which the exploits of their leader gave to the peasants. The field was cleared and Longueil again saved.

Big Ferré, overcome with heat and fatigue, sought his home at the end of the fight, and there drank such immoderate draughts of cold water that he was seized with a fever. He was put to bed, but would not part with his axe, “which was so heavy that a man of the usual strength could scarcely lift it from the ground with both hands.” In this statement one would say that the worthy chronicler must have romanced a little.

The news that their gigantic enemy was sick came to the ears of the English, and filled them with joy and hope. He was outside the walls of Longueil, and might be assailed in his bed. Twelve men-at-arms were chosen, their purpose being to creep up secretly upon the place, surround it, and kill the burly champion before aid could come to him.

The plan was well laid, but it failed through the watchfulness of the sick man’s wife. She saw the group of armed men before they could complete their dispositions, and hurried with the alarming news to the bedside of her husband.

“The English are coming!” she cried. “I fear it is for you they are looking. What will you do?”

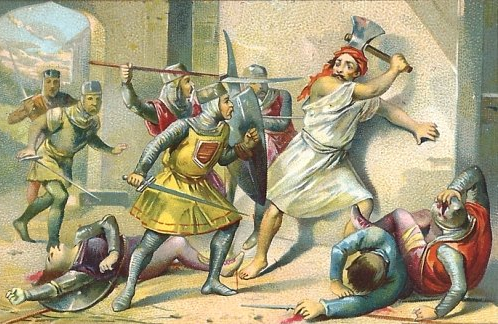

Big Ferré answered by springing from bed, arming himself in all haste despite his sickness, seizing his axe, and leaving the house. Entering his little yard, he saw the foe closing covertly in on his small mansion, and shouted, angrily,—

“Ah, you scoundrels! you are coming to take me in my bed. You shall not get me there; come, take me here if you will.”

Setting his back against a wall, he defended himself with his usual strength and courage. The English attacked him in a body, but found it impossible to get inside the swing of that deadly axe. In a little while five of them lay wounded upon the ground, and the other seven had taken to flight.

Big Ferré returned triumphantly to his bed; but, heated by his exertions, he drank again too freely of cold water. In consequence his fever returned, more violently than before. A few days afterwards the brave fellow, sinking under his sickness, went out of the world, conquered by water where steel had been of no avail. “All his comrades and his country wept for him bitterly, for, so long as he lived, the English would not have come nigh this place.”

And so ended the short but brilliant career of the notable Big Ferré, one of those peasant heroes who have risen from time to time in all countries, yet rarely have lived long enough to make their fame enduring. His fate teaches one useful warning, that imprudence is often more dangerous than armed men.

We are told nothing concerning the fate of Longueil after his death. Probably the English found it an easy prey when deprived of the peasant champion, who had held it so bravely and well; though it may be that the wraith of the burly hero hung about the place and still inspired his late companions to successful resistance to their foes. Its fate is one of those many half-told tales on which history shuts its door, after revealing all that it holds to be of interest to mankind.

[…] post Grand Ferré appeared first on Men Of The […]