Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History, by Bernadotte Perrin (published 1912).

But the Ancient History of the Greeks never emancipated itself wholly from the influence of the epic poems. The revolt against it which we see in the chronological and didactic poems of Hesiod, poems which were to tell men the truth in contrast to the falsehoods of Homer, is still expressed in the same hexameter verse. And even the later mythographers, or logographers, such as Acusilaus, who retold the epic legends in prose, merely lifted the myths to a slightly higher level of credibility by naïve rationalistic processes. The myths were not rejected, nor even approximately reduced to their historical meanings. The earliest rulers among men were still directly descended from gods, and a clumsy chronology by successive generations was made to show the connection of the great families of the present with these early demigods. Even Hellanicus, who established the first annual system of chronology for current events, and tabulated those of so late a period as the close of the Peloponnesian War, incorporated into his Attic History, to which Thucydides alludes, this clumsy fabric of Ancient History. It is Thucydides who first cuts adrift from it. And this gives us the succession of writers who sought by what they wrote to inform rather than to please; to tell the truth, to tell of what really was, rather than of what never was: Hesiod, Acusilaus, Hellanicus, Thucydides, all devoted to fact more than to form. Each in turn, it is true, accuses his predecessor of falsehood, Hesiod Homer, Acusilaus Hesiod, and so on down the line. This is one of the curious amenities of Greek historiography. But each is honestly in quest of the truth rather than of a pleasing form of the truth at the expense, it may be, of the truth. And Hellanicus attains his quest with a tabulation of the chief events in contemporary Greek history, first as they are related to the years of the priestesses of Hera in the temple at Argos, and then, after these sacred records had perished in the destruction of the temple by fire, as they are related to the annual archons of Athens, now an imperial Greek city. His work was an “annals,” in the strictest sense, and could have had no particular unity – no plan, culmination, or conclusion. It afforded not only no room for play of fancy, but none either for any artistic impulses. It was a catalogue of events by years of Athenian archons.

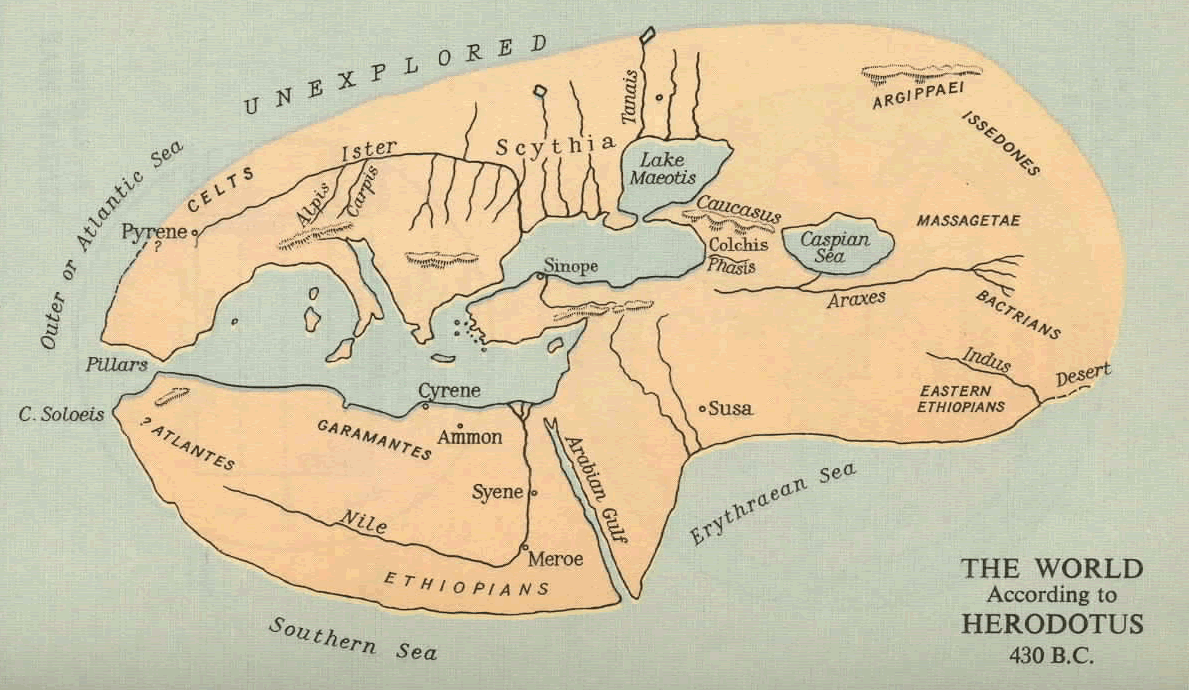

But meanwhile the really colossal events and personages of the Persian Wars, after being more or less fully recorded from the standpoint of Asiatic Greeks by Charon of Lampsacus, Xanthus the Lydian, Dionysius, and Hecataeus of Miletus, had also been committed to the processes of oral tradition, among a people of the liveliest fancy, from whom had come, by slow evolution, two of the greatest imaginative poems which the world has known. The wonders of Egypt and Assyria, the marvels of India and Arabia, the mysteries of Upper Asia and Scythia, had been brought by travelers and merchants within the reach and play of the lively Hellenic fancy. Wonderful facts and wondering fancy had ministered to each other for more than half a century, during which time a great Athenian empire had arisen, and the Age of Pericles had begun. Books were rare, but tales were rife, and there were professional tellers of prose tales as well as professional reciters of epic song. Written and oral material of tradition together made a thesaurus of fact and fancy before whose glowing charm even the epic cycle paled, and these bewildering treasures were reduced to splendid literary form by him who is called the “Father of History,” Herodotus.

Though born in Dorian Halicarnassus, and long resident in Ionian Samos and the Pan-Hellenic Thurii of Magna Graecia; though a traveler in all the parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe where Hellenes came into touch with Barbarians, Athens was his spiritual home, the Athens of Pericles. Here his immortal work, the materials for which had been slowly accumulating during more than thirty years of the most kaleidoscopic experience, was given at last the form in which it has come down to us. It was edited and published, as we should say, during the first decade of the Peloponnesian War, in Athens, probably, and for Athenians – at least in fullest sympathy with the imperial ambitions of Athens. It gives high artistic form to the reigning beliefs of the Periclean party at Athens concerning the Persian Wars, two generations of men after the wars were fought, and one generation after the greatest hero of those wars, Themistocles, had died. Meanwhile the oral tradition of those wars – and the literary tradition was annalistic and meagre – had suffered the changes to which all oral tradition is naturally liable, and, besides, had been directly influenced by an entirely new set of loves and hates and jealousies arising from the growth of the Athenian empire and the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. These tended to distort and pervert the stories of services to the national cause rendered by states now in hostile relations with Athens, and to glorify the services of Athens. So far as Herodotus writes history, he writes it as a defender of Athens and the Periclean policies which had led to the Peloponnesian War. He belittles the Ionian Greeks of Asia and their heroic but ineffectual struggle for freedom; he treats Sparta with ironical depreciation; Corinth, Aegina, and Thebes with contemptuous hate; Argos and Macedonia, with whom Athens hopes yet to come into alliance, with tender respect. He does this, as Professor Bury says, as “a historian who cannot help being partial,” rather than as “a partisan who becomes a historian for the sake of his cause.” And he does it at a time when, as Thucydides says, “the feeling of mankind was strongly on the side of the Lacedaemonians, and the general indignation against the Athenians was intense.” We cannot take the word of Herodotus in explanation of Sparta’s defense of Thermopylae, or of the stratagem of Themistocles at Salamis, or of the tactics of Pausanias at Plataea, although what he says enables us to penetrate to the truth of these matters. For he mirrors the sentiments of the community in the midst of which he writes. And this is his precise worth as a historian. We know through him what Periclean Athens liked to think and feel on these and other points.

“So far as Herodotus writes history,” was said above; for that is the least of what he does. He is a collector, on a vast scale, of historical material, and an incomparable artist in reducing this heterogeneous material to coherent and attractive literary form in an age when the footnote was unknown. Geographical, ethnological, mythological, genealogical, legendary, political, military, literary, economic, architectural, and religious data, in both genuine and fictitious sort, have been strung by him in bewildering profusion along one continuous thread – the strife between Hellenes and Barbarians from earliest times down to the capture of Sestos by the Athenians in 479. This greater theme, which gives his work the character of a universal history, was probably suggested to him by the narrower theme of Xerxes’ invasion of Europe; after he had treated this, he probably elaborated the larger subject. This narrower theme occupies the third triad of the nine books into which his history has been conveniently divided – books VII, VIII, and IX – and I am willing to admit, with Mr. Macan, though I do not think the argument for it can ever be made perfectly convincing, that these three books were “the earliest portion, or section, of the work to attain relative completeness and definite form.” They certainly constitute a distinct whole by themselves, progressively climactic in the stories of Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea, and they lend themselves to subdivision far less than the first six, or the first two triads of books. Mr. Macan well says that “no other equal portion of the work of Herodotus exhibits so remarkable a coherence, continuity, and freedom from digression, interruption, or asides as this the third and last volume, or trio, of books.”

In all the books, but especially in the last three, Herodotus is not a historian in the strict sense of the term – not as Hellanicus and Thucydides are historians. He does not seek by investigation to sift the true from the false and tell for all subsequent time what actually happened. He rather seeks to cast the vast material which he has collected on the narrower theme of Xerxes’ invasion and the larger theme of the strifes between Hellene and Barbarian into such shape as is prescribed by the canons of epic and dramatic poetry, the two regnant forms of literary art, but to do this in prose. He is the prose Homer, and to some extent the prose Aeschylus, of the thesaurus of fact and fancy constituted by the oral and written tradition of what was to him modern and recent, as contrasted with ancient and mythical time. His was the genius first to perceive that modern history in prose was capable of epic and dramatic treatment. Comprehensive discursiveness is the breath of his nostrils. The tales which Hellenes and Barbarians have told with or without pertinency, the marvels they have seen, the divine judgments they have illustrated, the wealth they have amassed, the crimes they have committed, their intrigues, loves, hates, and sorrows – these and more than these are welcome to Herodotus, and if he does not find them in sufficient abundance, then like a true Homeric poet he invents or adapts to suit himself. It is often hard to distinguish what he invents from what he merely accepts, and it often matters little, acceptance or invention being alike heinous from the standpoint of the true historian. Credulity alternates in his work with reserve, and both are often childish. He has lost his faith in the gods and heroes of Homer, for he has traveled in Egypt; but he has the most implicit confidence in oracles, and often warps his story to prove fulfillment of them. He borrows largely from a predecessor like Hecataeus, and pays him no thanks but ridicule. Andrew Lang’s priest in the City of the Ford of the Ox, who called Herodotus in the tongue of the Arabians “The Father of Liars,” said that he “was chiefly concerned to steal the lore of those who came before him, such as Hecataeus, and then to escape notice as having stolen it.” But all this simply emphasizes anew the fact that Herodotus was the prose Homer of the Persian Wars. Like Homer, he charmed his hearers and will always charm his readers. It was this charm which Thucydides could not forgive him. But Thucydides despised Homer. Those who do not despise Homer, but are edified by the play of fancy about fact, will agree with what Dionysius of Halicarnassus says about Herodotus: “Herodotus knew that every narrative of great length wearies the ear of the hearer, if it dwell without a break on the same subject; but, if pauses are introduced at intervals, it affects the mind agreeably. And so he desired to lend variety to his work and imitated Homer. If we take up his book, we admire it to the last syllable, and always want more.”

But it is a literary, not a scientific, enjoyment which Herodotus affords us. We know that the panorama of the peoples and tribes of three continents which he unrolls for us is colored by the fancy of the Greeks. Greek ideas and reflections are transferred to an Oriental or Barbarian setting. We can hardly find in Herodotus what Assyria, Babylonia, Lydia, Libya, Scythia, and Egypt really were in the sixth century B.C., but rather how they mirrored themselves in the Greek imagination. It is as though we had to reconstruct for ourselves a mountain range from its distorted reflections in the bosom of a lake. In this case, however, the distorted reflection has been brought into natural perspective for us by one of the greatest literary artists of the race. He had the genius to see, what is so easy for us now to see, that Salamis and Plataea were points toward which all previous Mediterranean history converged, and from which all subsequent Mediterranean history must diverge. To have had this vision first, establishes his right to be called “The Father of History.”