Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Shots Fired in Anger: A Rifleman’s-Eye View of the Activities on the Island of Guadalcanal, by Lt. Col. John B. George (published 1947).

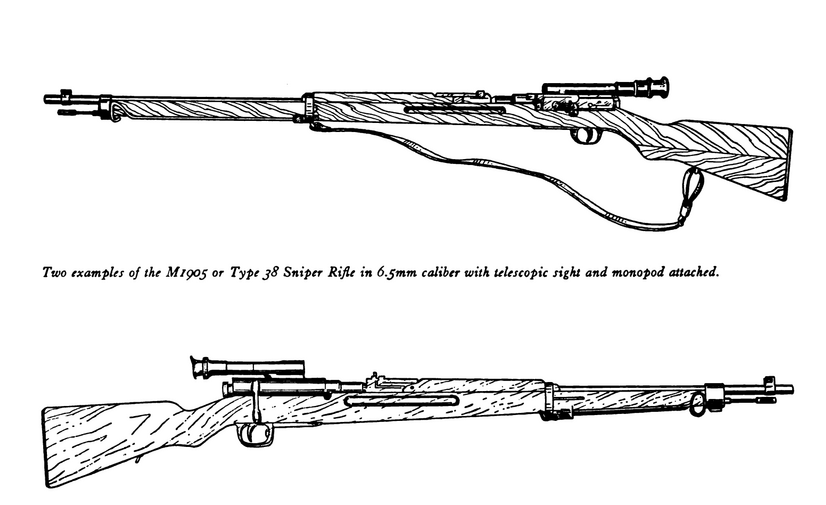

The M38 6.5mm Sniper Rifle

Though we had all heard a lot of talk about Japanese snipers who were reportedly using telescopic sights in other sectors, we did not capture any such weapons during the Mt. Austen fight. I was actually skeptical of their existence by the time we loaded up for Cape Esperance, though I knew that the Japanese were adept at the manufacture of good optical equipment from the few looks I had gotten at Japanese binoculars and mortar sights.

We all felt a marked tendency toward skepticism on that island because if there ever was a place rife with rumor, hokum and downright lies, it was Guadalcanal. All of us had heard lengthy stories of women snipers; about whole platoons of Japanese who spoke perfect English; and even one especially wild tale that Amelia Earhart and her navigator had been found alive in the island’s interior. Most of us even got to the point where we would believe what we could see and nothing else.

It had become a sort of religion with me to conduct a private crusade for truth — to challenge every abnormal account I might hear with the classic old Missouri quotation. I had stretched out on the ground alongside a score of Jap corpses, for instance, to prove that there were not any six foot Japs on the whole island and to abash a large number of men who claimed that they had just seen a six-feet-four body just down the road. So, whenever anyone came up with that old one I would always jump up, go down to the site which they had mentioned and go through the old ritual of lying down alongside the carcass. I knew that a man looked awfully big when he lay dead on the ground, especially if he were lying face up, but I had still become thoroughly annoyed with the constant repeated exaggerations by men around me and I had vowed to listen to them no longer with politeness. In the first three months I had never found a Jap measuring more than five-feet-eight; I had never seen a sniper rifle; and I had announced on several occasions a firm disbelief in the presence of either on Guadalcanal.

One day alter the big fighting was all over, I had the double embarrassment of being proven dead wrong on both counts. Within two hours I saw a Jap that was over six feet tall and a brand new M38 sniper rifle, complete with telescopic sight!

It was shortly after dawn one morning when some of the guards on the perimeter of our Tanamboga River camp saw a figure approaching down the trail. They didn’t shoot as he came in and I rather think that it might have been his height that saved him — he was so tall that he didn’t look like a Jap. When he got close he raised his hands and they saw from his uniform and belted-on equipment that he was an Oriental. With due precaution they led him to headquarters — one man in front with a Tommy gun pointing back and one man following behind. We were at breakfast when he was brought by the mess tent, and Art Hantel pointed at him across the table and motioned for me to turn and look.

“George,” he said, “I sure wish I had taken that $50.00 bet you wanted to make the other day; there’s a Jap that’s taller than I am!” Art was six-two; I turned around and looked in amazement but I still was slow to believe. “Betcha he’s a Korean or a northern Chinese!” I grunted back at Art but I didn’t answer when he reached into his pocket and asked, “How much?”

I walked over to my tent-shack and got out the little Japanese-English phrase book and then ambled over to the stockade. When I got there I was flustered further to find myself having to look up into the face of a Japanese soldier and I motioned for him to sit down on the ground. He hastened to obey, squatting low on his heels at once — not at all sullen, like some of the prisoners had been. I sat on a felled coconut log and began to communicate with him by means of the phrase book.

First I pointed to the set of characters which inquired of his age. He indicated that he was 23 years old by counting on his fingers. Next, I pointed to a line in which the English characters read “Where are you from?” Without hesitating he answered “Kobe.”

The questioning went on and on. “Where were you born?” “Kobe.” “Where is your home?” “Kobe.” “Where does your family live?” “Kobe.” “Where were you before you came here?” “Singapore.”

Well, that was definite enough. I went back to the mess tent and admitted to the other officers that my ideas on the height of Japanese were wrong — and I also told myself that the day had gotten off to a helluva start! It should have been some consolation to me to know that at least one person was really happy that day; and one was. When I left the stockade the Jap prisoner was noisily at work on a messkit full of spaghetti, fumbling awkwardly but cramming effectively with a fork. There was no doubt about the last few hours having wrought great improvement in his lot; and this didn’t make me feel a bit better.

Things got brighter, though, after I had finished my coffee; they always do. I had a nice sunny day to look forward to and there had been good luck fishing out in the bay for the past week so we had planned to go fishing again today. We had picked up several outboard motors (Evinrudes) and a couple of collapsible boats that the Japs had left and with a few emergency fishing kits obtained from the Navy we were pretty well set. But our troubles were not all ended, we discovered, when we tried to start the two outboard motors; each of them balked in turn.

Under these conditions back in the States, a man would probably have to make the damn motors work — but not so on Guadalcanal. We simply left the defective putt-putts where they were and went looking along the beach for another. We found one about half a mile down the beach hidden in the bushes with some other equipment. One of the officers with me got impatient with my taking time to rig a rope to pull the motor off its dunnage from a safe distance and walked right in, lifted it up and carried it out into the trail for examination; luckily it was not booby-trapped.

While he was examining the motor I became interested in three boxes which had served to keep it out of the sand. They were as large as burial caskets and very well built. I fastened a rope to the latch of one and dragged it out into the open, checking it well for evidence of booby-trapping before reattaching the rope to it. The same officer (far braver than I) got tired of seeing me fool with the rope and walked up to the box with a slice bar. I held my breath and closed my eyes while he tore it open. It didn’t explode and it proved to be a case of rifles, all in grease. One of them had a leather case attached to it and the breech appeared to be a bit modified. One glance told me that it was a sniper rifle.

I immediately lost all interest in fishing and begged off the trip, then took the rifle and telescope back to camp to examine more closely, carrying with me the bolts of the other six rifles which the case contained. There were still lots of Japs alive and free on the island so I sent a detail back to pick up the rest of the rifles, most of which appeared to be brand new M38 standard jobs, and bring them in to camp.

I was chided a second time when I got back into camp and it was discovered that my statement about Jap sniper rifles had been disproved by my own find, but I was so pleased with having the weapon that it didn’t bother me at all. I borrowed a can of gasoline from the kitchen and went off to my shack to remove the storage grease. The rust-proofing compound used on that particular rifle was stiffer and gummier than any I have seen on freshly stored American weapons. It was like old cosmoline which had set for twenty years.

The gasoline cut it, however, and it took me less than an hour to get the weapon ready to shoot, including washing each small part in a can and flushing and brushing out the inside of the receiver and magazine. The bore was like a mirror and the outside of the weapon had a new appearance.

As I proceeded with the disassembly and cleaning it became apparent to me that there were few modifications in this weapon from the Standard M38. The bolt handle had been bent down into the position Americans would consider about normal and a small rugged scope was fitted to the receiver by means of a dovetail arrangement which would permit ready removal.

The chief difference was, of course, the telescopic sight. It was very short, having an overall length of six-and-seven-eighths inches, excluding the rubber eyepiece. With the rubber eyepiece (reminiscent of the old Warner-Swasey type scope of World War I) it measured an inch and a quarter more.

It was mounted far back — a measure made doubly necessary by the Japanese shortness of neck and the very short eye relief of the glass, which measured something less than an inch and three quarters. It was mounted off center — to the left — in order to permit easier loading and passage of the bolt without too great modification of either the bolt or the receiver. With a 12 o’clock cut in the receiver, offside mounting was the only solution. This offset feature facilitated low mounting of the scope which, though it appeared at first glance to be hung way up above the receiver, was really mounted fairly close down, giving a clearance of only one-quarter inch (vertically measured) between tube and receiver cover. The receiver cover was retained on the sniper weapon.

The mechanics of the scope mount were good. It employed a massive dovetail joint, with the female section on the receiver end, surface vertical, and the male section an integral part of the telescope tube. The scope was fitted in the field by sliding it forward into the female joint until the rear shoulders of the movable base came to rest against the rear of the female joint. Then a rather awkward protruding handle on the outside of the movable base could be cranked from its forward position (open) to a rear ward position (locked), thereby securing the scope firmly in mount. The crank was held in place at the two extremes of position by means of two outward plunging poppets, which could be disengaged by pulling outward on the handle of the crank. At each extreme beyond the poppets there was a stud projecting to block the path of the locking crank, serving to prevent the lock being strained beyond its limit of normal tightness.

This crank turned an eccentric which caused the whole center third of the male dovetail (attached to the scope) to move upward and out of line with the front and rear portions, thereby creating a perfect triangular bearing within the dovetail. There was no ready means for taking up wear, but the bearing surfaces were so large that it was perhaps unnecessary.

The scope was nothing to marvel at but it was rugged and probably practical for the Jap soldier to use. It was certainly more weather-and-foolproof than the first ones which we were to be issued some eight months later. It was of two-and-one-half power magnification with a field of ten degrees and was so labeled in white letters on the scope tube. The objective was very small, not more than half an inch of glass, and the ocular lens was only a little larger. From the standpoint of appearance and function, based upon concepts of American hunting equipment, the scope was certainly not good. The only good point which was evident at first glance was its reticle. It was a simple three lines, graduated vertically in range settings for holdover and graduated horizontally for windage holdoff or lead.

This reticle left the entire upper half of the field clear of obstructions and the lower half of the lens was not even completely crossed by the vertical crosshair line. The lateral line went all the way across and had a few graduations marked near the center only. The vertical line was nearly all below the lateral one, with only a very slight protrusion of the tip above center.

The weapon was set dead on at 300 meters and all other ranges had to be held over or under. This would add even more strength to the idea that the Japs were coming more and more to realize the importance of accurate zero at short range. Fifteen hundred meters was the longest range marked on the vertical line and there was no provision established for correcting for drift at the longer ranges, other than the markings on the horizontal line, which were entirely too coarse for such purposes. The reticle of that weapon was the best military reticle I have ever seen in any telescope; and the telescope — with all its faults — was the best issued sighting device I was to see during the entire war.

Especially good were the weatherproofing measures which had been taken by the manufacturers of the scope. The lenses were firmly sealed, heavily protected from both moisture and shock by the stiff, close-fitting tube assembly. The outfit would obviously stand up very well under the trying conditions of humidity and changing temperatures encountered in the jungles. Once again, the Japs gave evidence by the design of their weapons that they were interested in practical results, rather than theoretical ad vantages. It is difficult for the average American “gun nut” to stomach the way the Japanese sniper rifle and scope flaunted the long-respected principles of design, which call for zero adjustment and ready means of allowing for drift, but it is a fact — whether we like it or not — that the Japanese sniper rifle was actually better than the ones we got for combat use later on.

The proof of the pudding, however, is always in the eating, so I decided to take the weapon down to the water’s edge and test it for accuracy by shooting at various-ranged targets.

To do this I got some boxes from the kitchen and smeared large charcoal bullseyes on them. Spotted at various points along the far curve of the beach they provided me with the ideal lazy man’s target range. I could shoot at various ranges without going to the trouble of walking back from the butts after each stage. Two men who had nothing to do volunteered to act as target markers.

I opened a fresh case of 6.5mm ammunition which we had in the dump we had captured at Esperance and selected several hundred rounds to use with this weapon. I have always had a great fear of firing a “booby-trapped” enemy cartridge, loaded with grenade explosive, so I carefully checked the neck of each cartridge to see that the bullet had not been tampered with after the round had left the factory. Fortunately, the Japanese crimping system does not lend itself to bullet pulling. You can generally tell by looking if a round has been disassembled. With that in mind, I went through the case, discarding any rounds which I thought were the least bit suspicious looking. I also tore several rounds apart and checked to see if the flakes of the powder appeared normal; they all did. Actually, I have never come across a proven instance of the planting of exploding ammunition by the Nips, but at that time I was still following the doctrine that a soldier should always give his enemy credit for as much intelligence as he himself possesses. It took sometime for us to learn that this doctrine did not hold true for the Japs; they missed a lot of good bets.

In a half hour the whole thing was set — the gun, the range, and the targets. There was no rest handy at my selected firing position and I looked about for some time until I remembered that I had a monopod on the rifle and might as well use it. It opened out from the rifle easily and I stuck it into the sand to the right depth and took aim. By cradling the stock in my arms and laying on it while the long front end of the rifle was held up by the monopod, I could secure a very comfortable and steady hold. I dry fired a couple of shots from that position and then loaded up and yelled a warning to the pair of men who were to mark. They got into defilade before I fired the first shot. By arrangement they were to come out after each shot was fired and mark; I would fire only one shot at a time.

I fired at the short ranges first, taking the initial five shots at a five-inch bull on the target closest to me — as near 100 meters as I could estimate. All of these shots were bulls. The sixth was a bad hold and went out at three o’clock — just where I called it. A walk to the target and a look at that first group convinced me that the rifle I had was a good shooting weapon. The entire six shots had an extreme of less than four inches — enlarged by an inch and a half by the single wild hold. I went back to the firing point while the two men who were marking, impressed like myself by the rifle’s performance, moved away to the next target.

At 200 meters the weapon kept almost everything inside eight inches, even with some bad holding involved and I found that the reticle holdover mark for that distance was perfectly placed. I fired shot after shot at that range because I wanted to be especially sure of that setting.

To make a long story short, the gun continued to behave beautifully, not missing any of the settings for ranges up to 400 meters. Beyond that I didn’t bother to test the weapon. By firing 100 rounds I had adequately tested the worth of the scope and rifle and I was satisfied that it was a surprisingly good outfit.

To check the zero-return qualities of the scope mount, I took the scope off the rifle several times during the firing, with no noticeable change in the point of impact. There were no ready adjustments on the scope, which I naturally recognized as a fault, but at least the Jap soldier would not be able to ball up what zero his rifle had been given at the arsenal. That was more than could be said for our Weaver-Springfield.

The 6.5mm cartridge was not new to me at that time, as I had fired it in both the carbine and rifle versions of the M38, so I was not as much impressed with its qualities as the Infantryman who had not done extensive shooting would be. These qualities made for extreme ease in shooting — a marked characteristic of the long 6.5mm weapons.

Compared with our own Springfield it can be said that this Jap sniping gun had practically no recoil or muzzle blast. They didn’t even jump badly when fired from the hip. And the great giveaway of the Springfield or Garand — the great kickup of dirt and leaves by the muzzle blast in front of the firer’s position — was comparatively nil in the Arisaka. To the ordinary rifleman this would be a great advantage and to the sniper striving for concealment it would be a godsend.

This exhibition of accuracy had stimulated my interest in the gun and as I took it back to camp and began to clean it, I looked it over with increased care. On this closer examination it was clear that the weapon was much better fitted and finished than the minerun Arisaka 38. The inletting of the stock was to closer fit and the firing mechanism and bolt were tighter. The trigger pull, while by no means up to American match standards, was smooth and broke, as I remember, at about five pounds. For a Jap weapon that is marvelous, as all who have fooled with them will know. The bent bolt tended to put the gun on better terms with me, as did the smooth fitting, jag-tipped cleaning rod with which it was so very easy to keep the bore clean and free from rust. I used American bore cleaner on the gun, and it worked beautifully (the Japs apparently used a chlorate primer, too, as I have seen some of their barrels rusted overnight).

It was a slick little weapon, that rifle, although in its present condition it was long, heavy and ungainly beyond all practical use. But if I had not possessed a sniper weapon of my own, I would most certainly have cut that rifle down to a decent size and used it in preference to any gun — American or Japanese — with iron sights. With the receiver of the sniper rifle removed and fitted to the rest of a M38 carbine, I would have had a good substitute sniper rifle, much better, in my opinion, than the Weaver-sighted Springfield which we eventually got.

As it was, though, we didn’t get back into the fight for some time, so I turned the weapon in at headquarters rather than to have to nurse it all the way back to Fiji with my baggage (which consisted of the greens on my back, my rifle, and a small ruck sack, improvised by sewing Infantry pack straps on a Jap bag).

My experience with this rifle was of no particular consequence but it did provide me with another beef against old “Colonel Whoever-Was-Responsible.” It drove home the fact that at the beginning of the war the Japs had a sniping rifle which was as good and maybe a little better than anything we issued in worthwhile quantities at a much later date.

(Continue to Part 6)

[…] (Go back to previous chapter) (Continue to next chapter) […]