Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

In the great gallery of American gunmen, there stand all sorts of men. Long-haired, buckskin-clad frontiersmen walk arm in arm with booted and Stetsoned cowboys. Frock-coated, pallid and still-faced amblers jostle others who are hardly to be distinguished from those ordinary citizens who walked the streets in their day.

In this last bracket fell that square-jawed, thickset Wizard of the Pistol; that black-haired, blue-eyed Typical Gunman of the great, inky mustache — Ben Thompson, who was variously printer, Confederate soldier, professional gambler, peace officer, and a gunslinger second to none that Texas has ever produced.

Anything like a correct tabulation of Ben Thompson’s killings is impossible to compile. For he was charged in some quarters with many murders that he, or his friends for him, vehemently denied; and like most gunmen of the ’80s, he doubtless committed several killings of which few but himself had knowledge, and of which he preferred not to talk.

By his own statement, he was born in 1843. Whether he was born in Yorkshire, England, or near Lockhart, Texas, has long been a disputed point, but that he began life as a printer seems well authenticated. He drifted about from place to place, following his trade, until eventually he reached New Orleans. His account of his adventures at this time are the only statements handed down to us. There is no substantiation possible, for much that he said. Today, just as during his lifetime, one must either believe, or decline to believe, Ben Thompson. It is merely a matter of deciding for oneself his credibility in any given instance. I have tried to weigh all evidence impartially — and I have known several men who knew Thompson; who were familiar with his record as he was making it.

He was fond of telling of how a young Frenchman in New Orleans was upon a time insulting a girl; and of how he, Thompson, full of Southern chivalric ideas, interfered, with the result that a duel was arranged between himself and the Frenchman. By Thompson’s account he demanded that the Frenchman fight with pistols at ten paces, the shooting to continue until one man or the other was dead or incapable of continuing. This mode was rejected as “barbarous.”

In these negotiations, Ben says that he refused to fight with swords, but countered with the suggestion that the two of them go alone into a dark room, armed with daggers, there to fight until the death. This was accepted.

Well, he killed the Frenchman, but it seems that the code duello operated in the romantic Crescent City at this time only for the aristocrats and, to these proud Creoles, Ben was, of course, hardly more than a street arab. When he came alive out of the room, the friends of the dead challenger raised a hue and cry against Ben as a murderer, but he found sanctuary in the Sicilian quarter and eventually — disguised as a Sicilian — escaped from the city and made his way to Houston, Texas, and then home to Austin.

After this return to Austin, he began the career that he followed the rest of his life, that which he preferred — the career of a professional gambler. At the beginning of the Civil War, he enlisted in Baylor’s regiment, but he was not designed for a soldier. His whole army experience was one fierce round of brawling with his superiors. He shot a sergeant at Fort Clark, in a row over rations he had stolen and the return of which the noncom demanded. Lieutenant Haigler then crossed him, according to Ben’s account, and received a fatal wound in the neck.

Ben escaped the guardhouse and stayed out of sight until the expiration of his enlistment term. Apparently the lawlessness of the State of Texas of those days governed the Confederate Army also. For Ben appeared again at Fort Clark and calmly reenlisted, nor was he ever tried for shooting the sergeant and murdering the lieutenant. His time in the army was, more or less, mere indicator of his life to come. He was naturally of the chip-on-the-shoulder type; naturally a “sporting man.” He ran gambling games for the soldiers; he smuggled liquor into camp. He obeyed his officers only when that could not be avoided.

He served on the border, always managing to be in hot water of some sort. He killed two Mexicans in a gambling row in Nuevo Laredo. He was hotly chased by the aroused Mexicans and had many wild adventures in escaping. Finally, he was detailed by his superiors to raise a company of soldiers in Austin. That was a touchy town in Civil War times. Ben proceeded promptly to get into a row with a desperado named Coombs, who chanced to be a member of the Home Guards. He killed Coombs, and for once this combative bulldog seems to have been at least no more at fault than his adversary.

After the war, he was arrested by the Union military authorities, then scourging Texas in the tragic mess of “Reconstruction.” Ben escaped and joined the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico. When Maximilian was executed, he returned to Texas and stood trial for the killing of Coombs. The jury acquitted him without leaving the box. But he was immediately rearrested, charged with assault to kill one Brown. For this assault, he served two cruel years in the penitentiary.

But they couldn’t break the spirit of a man with the jaw of Ben Thompson! After his release, he plunged into gambling and drinking and drifting. The wild trail-herd towns knew him — knew the roar of his pistols and the whir of his cards. He hit Abilene, Kansas when that “cattle capital” was in the blazing heyday of her brief glory, with Wild Bill Hickok for city marshal. Here Thompson found an old friend from Austin.

Phil Coe, as the oldtimers recall him, was a handsome six-footer, of splendid brown mustaches and beard, who was the very fashion plate of the successful gambler. After the Civil War he and a partner, Bowes, ran a saloon on Congress Avenue in Austin, Ben Thompson conducting the games in the Coe-Bowes place. He and Thompson opened the Bull’s Head Saloon in Abilene and for a time got on well with Wild Bill.

Then these two, Coe and Wild Bill, fell out. Thompson says that they quarreled over the favors of one of the fair Cyprians of the town, Jessie Hazel — so her name comes down to us. They were both magnificent bull-elk, but Coe won the lady and left the famous Wild Bill gnawing his golden mustache and plotting dire revenge.

Somewhat later, Phil Coe went out with a bunch of fellow-Texans, cowboys, to celebrate. He did something that nobody in Texas had ever known him to do — he brandished a pistol. Men who saw him every day in Austin “reckon he must have carried a gun,” but cannot recollect seeing him with one. He was not a gunman. But on this occasion, he “shot off his gun.” This was a violation of the ordinances of Abilene.

Wild Bill appeared instantly on the scene, ready for action — as he had a habit of appearing. What occurred, then, exactly, has been much disputed. But there is no doubt that Coe was no match for Hickok; and that he died with two bullets from Wild Bill’s derringer in him, having bungled his own shots.

When word came to Ben Thompson that his old friend and partner, Coe, had been killed, he was furious. But at the moment he was bedridden as the result of an accident. It was months before he recovered and when he left the country to return to Texas the account with Wild Bill was still unsettled. I think that there can be no doubt that Thompson would have liked an encounter with Hickok. To his dying day, Thompson expressed the greatest contempt for Wild Bill and his like and the old Texans — many of whom had no liking for Thompson — still tell of the way he crossed Abilene’s marshal at every opportunity.

He was a human bulldog, a human gamecock, this squatty man with the prognathous jaw. I hold no brief for him, but as a matter of judgment, one must see the man as he really was. Perhaps we can see him more clearly, today, than would have been possible fifty years ago. Much of the heat of those controversial times has vanished; we can evaluate the Thompsons and the Hickoks fairly, judging them by their records. We need not be apologists nor partisans.

Every word that I have ever heard of Thompson strengthens my belief that he belonged to that pugnacious breed of which the frontier has always produced plenty — men owning, not courage in the real sense of the word, but an instinctive belligerence like that of a wild animal. In the old Texas phrase they “didn’t know enough to be scared!”

Thompson was of this breed. His every action shows a senseless disregard of the most elementary caution, discretion, common-sense. And so I find partisan accounts of his backing down before this man or that utterly at variance with everything I know about Thompson. It is not that he was too brave to give way, it is that no believable record has come to me, of Thompson giving way even when he should have stepped back, when it was the sensible thing to do.

And so I find the account of Wyatt Earp backing down a shotgun-armed Thompson in Ellsworth — particularly a Thompson backed by wild-eyed Texas cowboys! — highly unconvincing, to use no stronger term. Stuart Lake had the tale of this from Wyatt Earp and others of the Earp faction. All my life I have heard the story of the killing of Sheriff Whitney by Billy Thompson, and the subsequent rioting, in very different fashion. Granted that my informants were Texas men who were in Ellsworth with trail herds at the time, it must be remarked that they were many of them men who did not drink, did not gamble, had no good word to say of the brothers Thompson.

You will find Lake’s account of the Ellsworth business on pages 88-96, in his Wyatt Earp. I have always figured that Friend Lake suffered from a bad attack of hero-worship while in Earp’s company, nor is it any secret that I hold this conviction. My own opinion of the Earps is not very high, nor can I get enthusiastic about any of the crowd the brothers ran with. Since the anti-Texans have been so free with their nasturtiums directed at the men who brought cattle up the trail, it seems no more than fair to recall that the Texas men were wont to describe Wild Bill Hickok, the Earps, Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, Charley Bassett, Luke Short, Mysterious Dave Mather and the rest of those cow-town marshals, as “The Fighting Pimps” — an appellation doubtless suggested by the fact that most of them hung out in the bordellos of the towns.

Ben Thompson’s stay in Austin was brief. His money was almost gone and the business in which he had partnered with Coe had been “settled” by the authorities in his absence. He accused Hickok of profiting most by the settlement. He came north to try for another stake in Kansas. A visit to Abilene (Wild Bill was no longer there) recovered nothing of the Coe-Thompson property. He went back to Ellsworth where Billy Thompson was working for cowmen and gambling on the side.

By pawning jewelry and borrowing money, Ben got enough to open up gambling rooms. Neill Cain dealt monte for him and Cad Pierce and other cowboys bucked the games. A good deal has been said about the animosity of the Texas men for the Northerners, a dislike explained by the Texans’ “unreconstructed Confederate sympathies.” Perhaps there were other reasons for the cowboys’ dislike of the authorities…

The “fighting marshals” were apt to ensconce themselves behind convenient shelter, when “quieting” the Texans. From this cover they emptied their shotguns into the cowboys’ ranks. And the men who hired the Bat Mastersons and Earps were only too often hardly the type to inspire confidence in an unprejudiced observer. So, in Ellsworth, the cowboys accused the officers of city and county of fake arrests, shake-downs of drunken cowboys, petty graft of every description. And Ben Thompson was their natural champion and the natural enemy of Deputy Sheriff Hogue and his fellows of the city force.

The Ellsworth papers were inspired by partisanship — naturally! And are in consequence hardly to be depended upon for unbiased reporting. There were too many axes to grind!

A row broke out in Thompson’s place August 18, 1873. Primarily, it was between Thompson and a gambler named Martin. But events crowded so fast upon each other that the truth was hard to get at, afterward. The result of the argument was that Martin slapped Ben Thompson in the face and Thompson promptly whipped out his pistol. “Happy Jack” Morco, one of Marshal Norton’s deputies, interfered in time to save Martin’s life.

Morco — himself a gunman with a record and one of Ben Thompson’s bitterest enemies, Deputy Hogue being the other — hustled Martin out into the street. But he returned with a bunch of friends and began to yell at those in Thompson’s to come out.

“Come out, you Texas fighting ——!” Martin yelled.

Thompson was not the man to invite to a row, unless one really wanted him to appear. He snatched up a Henry rifle, brother Billy grabbed a shotgun. They ran to the door and here Billy, who was about half-drunk, managed to let his shotgun go off at nothing. But the party outside took the will for the deed and left there. The Thompsons then came out into the street and took shelter behind a fire engine. The alarm sounded up and down the town. It was made out a clean-cut issue be tween Ellsworth citizens and Texas cowboys. Armed men began to swarm about the streets. Violent threats were hurled back and forth across the street where the townsmen faced Ben Thompson — but not too closely. Deputy Hogue, with Happy Jack Morco, the deputy marshal, were attempting to work up the townsmen to make a dash at the Thompsons’ position. Ben and Billy were still alone in the street, but behind them in the hotel the cowboys were “forted,” waiting for trouble.

Hogue worked closer, trying for a shot at the Thompsons. Almost in range of Ben’s rifle, he stuck his head out of a window of a building. Ben whipped up his rifle and took a snapshot at the enemy, but Hogue jerked in his head quickly. Thompson then tried to shoot through the plank wall that sheltered Hogue. The bullet missed but it waked in Hogue a burning desire to emigrate. He left town and ran across the river, to stay there until the war was over.

Happy Jack Morco was another who profited that day by the poorest shooting Ben Thompson has ever been charged with. And he, too, decided that he wanted no more of this battle.

Sheriff Whitney was, to all intents and purposes, a friend of Ben Thompson’s. Ben always insisted that he was and I have never heard anything which would lead me to believe that his death that day was anything but the accident it was claimed. The sheriff appeared during the shooting. He held a conference with Ben Thompson. The retreat of the two officers, Hogue and Morco, had left the mob with time for thought. Hostilities were slackened. It was at this time that Whitney appeared and persuaded Ben not to look for further trouble.

There are two conflicting accounts about the manner in which Whitney met his death. If we take the version of the Ellsworth ring or certain present-day chroniclers, Billy Thompson saw Whitney on the street and calmly walked to the door and emptied a shotgun, “to get him a sheriff.” The other account, which I have heard all my life, seems to me more plausible, if nothing else.

By the latter account Thompson, with his brother Billy and Sheriff Whitney, were walking toward the Grand Central Hotel when Ben — keeping watch in the rear for enemies — saw Happy Jack some fifty yards away, at the corner of a building. Happy Jack ducked back as Ben let go a fast shot at him. With sound of the shooting Whitney and Billy both whirled about. Billy lifted his shotgun and fired and, being still under the influence of liquor, did both things clumsily. The load struck Whitney. Billy was shaken by this accident. He told Ben and told others that he had stumbled while trying to get a quick shot at Happy Jack Morco.

Ben knew that Billy was in trouble, now. He insisted that his brother get out of town, get clear out of the country. With the help of friends, Billy was at last armed and mounted and started off. Ben and several Texas men were armed and waiting for trouble when Deputy Sheriff, now Acting Sheriff, Hogue appeared with a posse. Hogue informed Thompson that he was ordered to arrest him for the killing of Sheriff Whitney. Thompson absolutely refused to be disarmed or to submit to arrest.

It seems a reasonable assumption that, if Thompson had put down his gun, in the presence of officers with the killing reputation of Hogue, Charlie Brown and Ed Crawford, he would have been murdered instantly. That was the Texas opinion of these men.

Thompson informed Hogue that while he would not submit to arrest in those circumstances, he would surrender to some official in whom he had confidence, one who could make and keep reasonable guaranties. Mayor Jim Miller now appeared on the scene and promptly discharged the whole police force. To Miller Thompson made his proposition: If the Mayor would disarm Happy Jack Morco and keep him disarmed, he, Thompson, would surrender to the mayor. Larkin, proprietor of the Grand Central Hotel, stood sponsor for Thompson’s good faith. So Jim Miller then disarmed Happy Jack. To the mayor then, Ben Thompson surrendered, and was released in the sum of $10,000 cash bond.

Ben was eventually acquitted of complicity in the killing of Sheriff Whitney. But scapegrace Brother Billy was indicted, and though he stayed on the dodge was finally captured, extradited from Texas and put on trial. He was then acquitted.

Ben “took a pasear,” as the old-timers say, over to Leadville, Colorado. His reputation and the manner in which he conducted himself there and everywhere, is rather vividly shown by this “dispatch” taken from an Austin newspaper:

“Ben Thompson, who is well known around Austin as a professional gambler, has been doing Leadville in his old familiar style. But he does not seem to have played it quite so successfully as he sometimes did in Texas.

“Ben was never known to labor very industriously — except with his thumb and forefinger when pulling cards from the box behind the faro table, or sitting in front of it wrestling with the tiger. A gentleman now in Leadville, who knows him, writes that some time ago Ben tried the faro table and lost two thousand in money, a diamond stud worth eight hundred, and a watch and chain worth three hundred, in one sitting. He had to borrow some money to start for home. But he did not start soon enough. He got drunk and turned over gambling tables, shot out lights, ran the crowd out of the house, pounded one man up with a six shooter and wound up by cleaning up the street with a Winchester.”

Broke, and possessed of no abilities except his skill as a gambler, and his proficiency in Six-shooterology, he was glad to enlist as a gunman under the banner of the A.T. & S.F. Railway. A good deal has been gossiped and written about Ben’s connection with this fight between the Santa Fe and D. & R.G., but my old friend, Major A. B. Ostrander, of Seattle, writes of the row as he, a veteran railroad man and actual participant, witnessed it:

“The A.T. & S.F. had completed their line to Pueblo. They wanted entrance to Denver, and to get it, they leased the D. & R.G. Road, supposing that this lease included the proposed building of their extension to the Royal Gorge. This, the D. & R.G. stubbornly denied, and attempted then to break the lease. So a genuine war followed. “The Santa Fe put armed guards on all their trains and, to protect their roundhouse at Pueblo, they employed the noted Ben Thompson. They brought him up from Texas with ten ‘good men,’ to protect the round house.

“When Governor Hunt and Pat Desmond (who was the city marshal of Pueblo) went over the road turning out all employees (I was ‘captured’ at Fort Garland) the officers and prisoners returned toward Pueblo. When our train was within four miles of that place, we were met by a handcar filled with D. & R.G. men, who informed us that the roundhouse had been turned over to them without the firing of a shot. This amazed everyone who knew Thompson’s reputation. Upon arrival at Pueblo, we learned the facts:

“Ben and his men had held the house until exactly five minutes before twelve o’clock noon, the hour when the Santa Fe eastbound express was scheduled to leave. Ben and his men came out at 11:55, delivered their Winchesters to the D. & R.G. forces, boarded the express and went calmly on their way back to Texas. It was stated then and there that an emissary had got word to Ben that twenty thousand dollars awaited him at the door if he would come out peacefully. Well, he did! Thereby — incidentally — he saved lots of bloodshed. I was all through that fight and knew all the circumstances at the time.”

Major Ostrander’s version of this episode is one which has long been related in the West. Thompson (rather naturally) always denied that he received a cent for coming out and giving up the property which he had been paid five thousand dollars to hold to the death. He always claimed that he had been “relieved by proper authority.” However that may have been, certainly he got back to Austin, as usual, and — as usual — went back to gambling.

As he grew older he “went oftener to the bottle and stayed longer.” When drunk, he was apt to let his very primitive sense of humor range beyond the limits favored even by cowboy wits, in the matter of horseplay. He once shot up his own gambling house because of a falling out with one Loraine, his partner. The police walked clear of Ben and made no bones about it, because of his long, red record as a gunman.

So, Ben was permitted to sober up from his sprees and apologize — if he chanced to feel apologetic at that time — for whatever promiscuous shooting he might have done. He and his friends always explained deprecatively that he was a bit wild when drinking, but, when sober he was the best of men, the fondest of husbands and fathers, and very, very kind to his aged mother.

The marvel is that he was not quickly killed in some of his drunken brawls. Shakespeare has something to say about wine’s tendency to “increase desire and defeat performance.” This is as true in pistol-play as in the field the Bard meant. Men knew it, too. But nobody “took advantage” of his times of fuddlement.

The greater marvel is that Ben Thompson could have been made city marshal — chief of police — of a town like Austin, capital of Texas. But he had a large following among the sporting crowd and the denizens of the half world and, like many of his kind, he was a queer mixture of intense loyalty to those he liked — so long as they didn’t irritate him — and hair-trigger suspicion of everyone on earth.

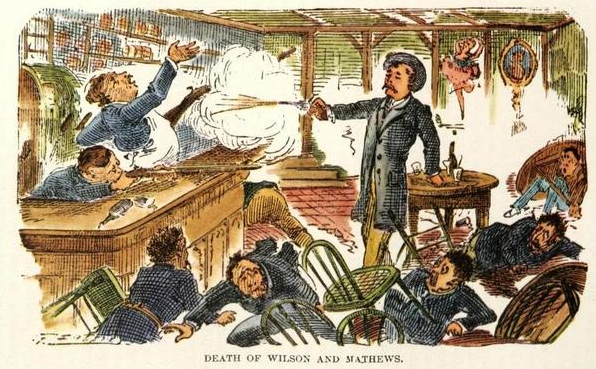

He was twice a candidate for marshal. The first time, he was soundly defeated and, before making his winning campaign, he engaged in a gun battle with Mark Wilson, owner of the Senate Saloon and Variety Theatre. Thompson went into the Senate on a Christmas Eve, gently bent on raising a row and busting up the performance in his usual humorous fashion. It was not the first time he had bothered the Senate. Mark Wilson had word of Ben’s intentions; he had been made a special policeman; was armed and waiting and a trifle more than willing.

The row began as Thompson planned it. With the first sound of disturbance, Wilson rushed out, hunting for the disturber.

Thompson interfered and slapped Wilson in the face, cutting the saloon keeper with a heavy ring he wore. He was armed, of course. Nobody ever saw him otherwise. According to reports, he wanted only the shadow of an excuse to kill Wilson. There is no doubt that he was ready to shoot, then as always, on slightest provocation. Certainly when Wilson went back to arm himself, Thompson watched him; watched him like a hawk.

Wilson came out with a shotgun, fired blindly at Thompson, missed and fell with the ready Thompson bullet in him. The bartender was afraid that Ben Thompson would kill him next. He fired at Ben but without much accuracy. Then he ducked back behind the bar. But Ben drive a bullet through the wood panel of the bar and into the back of the luckless drink-dispenser’s neck.

Wilson had been shot four times and was dead before the bartender fell; the latter lingered a few weeks before dying.

Now, having been duly acquitted for this pair of killings — Thompson became Austin’s city marshal. Blinking back through the mist of the years, Ben Thompson’s friends say that he was a good marshal. But those citizens who fought bitterly against the appointment of the most notorious gunman of Texas as chief of police, remarked that he was merely less humorous — in the manner that “humor” took him when drinking.

At any rate, we can be sure of one thing — that no longer was the Austin police afraid of anything or any one on earth!

In San Antonio, at this time, the Vaudeville Variety Theatre on the main plaza was run by an unusual one armed man, Jack Harris. He had served in the Confederate Army with Thompson. Before that, he had been scout and guide for General Albert Sidney Johnston, during the campaign of 1857, against the rebellious Mormons in Utah. He was “nobody’s soft spot!”

There was, of course, a drinking and gambling saloon in connection with the “theatre.” Joe Foster and a one time Austin boy named Billy Sims were interested financially in “The Vaudeville” which was, at the time, one of the most notorious joints in the state.

If Thompson and Jack Harris were at the moment quite friendly (and” it do seem”, to one unbiased observer, that they were birds very, very much of a feather!), between Thompson and Sims there existed enmity from times past, in Austin. Sims’ father had been a stone mason and afterward a policeman, in the capital city. Billy Sims became a gambler and Ben Thompson, disliking his competition in the matter of keno, shot up the Sims game and ran Billy Sims out of town, to San Antonio.

Prior to his election as city marshal of Austin, Thompson had often gambled in the Harris place. On one occasion, he and Joe Foster, the dealer, rowed over the game. Ben had seesawed. At first, he had lost heavily, then won back a part of his losings. But when Joe Foster asked for the balance owed to the game, Ben called him thief and cheat and threatened to kill him. He stalked out, without settling.

Jack Harris’ friendship for Ben Thompson died right there. He said that nobody could come into his place and question the honesty of his dealers. It would have been a fatal weakness for any gambling house proprietor to condone conduct of this sort. Every tinhorn and would be gunman in the country would be trying the Thompson method of avoiding losses. This marked the breaking up of the intimacy — however deep it may, or may not, have been, between two men of this kind — which had on the surface existed between Ben Thompson and Jack Harris. In its place, came the bitterest of enmity. Jack Harris proclaimed loudly that he unqualifiedly backed up Joe Foster.

After he became marshal of Austin, Thompson heard threats that Harris was supposed to have made. He concluded that he must eventually go down to San Antonio and interview Harris. While the saloon keeper was one armed, he was noted as an expert shot. Also he seems to have had plenty of the same sort of bulldog bravery that Ben Thompson owned. Certainly, he was in no wise awed by Thompson’s record as a gunman. To the friends who told him just what to do and how and when to do it, he only remarked that he could kill a bird on the wing so, he thought he could “kill a man standing.”

Occasion came for Ben to go down to San Antonio and, since he was not one to hide his light under a bushel, his presence was doubtless well-known. While there, he was informed that Harris was on the street “looking for him,” and armed with a double-barreled shotgun. Through the influence of friends, Thompson was kept from the street that day; he remained in his room in the hotel. The next morning, however, he met Harris and asked if he were looking for him the night before.

“No,” said Harris. “I was not looking for you, but I was waiting for you; and if you had come about my place I would have filled you full of shot!”

There would have been a fierce encounter then but a deputy sheriff intervened. Later, Thompson went down to the variety house bar and inquired of the bartender where Harris’ famous “Shotgun Brigade’’ was. He had heard that they were “forted up” for him. He sent several insulting messages to Foster and Harris — or, rather, he asked the bartender to deliver them. But, apparently, this man of drinks was no more intimidated by the famous Ben Thompson than was his employer, Jack Harris. He told Ben shortly and grimly that if he had any messages to deliver, he could deliver them himself!

Later the same day, Thompson reappeared in the bar with a friend. Again, he asked about the Shotgun Brigade. Was it still “forted” for him? Harris came into his place and was told of Thompson’s visits; of his drink ing and of his threats. Harris armed himself with a shotgun and was standing at the door leading upstairs into a ticket room when Thompson caught sight of him through a Venetian blind.

“What are you going to do with that shotgun?” Thompson says he called.

Harris — according to the account given by Thompson’s personal attorney — replied that he was going to shoot Thompson with it. Ben’s pistol was out. He fired three times instantly; the first shot knocking Harris over, the second striking him as he fell, the third being to frighten off employees of the place who might have an idea of interfering.

For this killing he was indicted and acquitted. It was the ancient way of Texas; of the frontier. These two men were armed; they were bitter enemies; and each had made threats against the other. No other verdict was possible in a fair court. Certainly not in any Texas court of that day; nor, for that matter, in any Texas court of today!

As soon as he was indicted Thompson was brought to see the propriety of resigning his office as marshal. Thereafter, he had no official station whatever. After this acquittal, he had to busy himself on behalf of that restless young man, Billy Thompson, who seems to have been second only to Ben in his sheer genius for getting into trouble. This time it was a murder charge in Refugio County; a business of several years’ standing. Ben had plenty of money and the expert array of lawyers he hired soon brought an acquittal for Billy.

Parenthetically, Billy was of course in no wise to blame for this murder. For this assertion, we have the assurance of no less than the Honorable Major Walton. And who should speak with more authority than Major Buck? (A really famous lawyer.) Was he not Ben’s attorney for pay; his staunch admirer and unpaid press agent in and out of court; his biographer?

(Continue to Part 2)