Editor’s note: The following account by Kennett F. Harris is extracted from The Chicago Record’s War Stories (published 1898).

“Anyone who wants to go back to the United States when this cruel war is over can go; for my part, I intend to stay.”

Capt. W. O. O’Neill of Troop A, 1st Volunteer Cavalry, leaned back against a roll of blankets beneath a stretched square of canvas after the fight at Guasimas, and, blowing a thin stream of cigarette smoke from his lips, made this declaration. From where he reclined he could see a wide stretch of open ground covered with waist-high grass blown into far-reaching ripples by a rare breeze; a border of dark-green manigua, from which arose broad and leafy mango trees, grace fully drooping crowns of palms; cedrelas, with trunks like polished bronze, and here and there the well-named flamboyants, bearing their masses of blossoms of flaming scarlet. Beyond were the hills, meeting the intense blue of a cloudless sky, and within hearing, when the first sergeant ceased pounding coffee with an ax handle in his tin cup, were the musical plash and ripple of a brook clear as one of his own Arizonian streams. Like many another man, Capt. O’Neill was well pleased with Cuba. The possibilities of the fertile soil and the hidden wealth of the mountains appealed to the practical side of his nature as the picturesque beauty of the landscape did to his well-developed artistic sense.

“I’m going to stay,” he repeated.

Cuban ground holds the dust of many high-souled and brave men, patriots and warriors, who, counting honor and freedom above all things earthly, lightly risked and heroically lost all else, that their country might be redeemed from tyranny and oppression, but it holds the dust of none braver, kinder, more generous than Capt. O’Neill.

I like to think of him now as I saw him then — a picture of robust manhood and perfect rest. He had thrown off his blouse for greater comfort, and his blue flannel shirt was unbuttoned at the throat; his hands were clasped behind his head and the brown cigarette between his lips was burning evenly and well. He was at peace with all the world and was inclined to be charitable even toward the Spaniards, concerning whom one of his brother officers had spoken unkindly.

“They can’t help being Spaniards any more than a skunk can help being a skunk,” he said. “God made them that way. Did you ever get close to a skunk and watch him — when nothing has occurred to irritate him— going to get his evening drink, for instance, gliding over rocks and logs with a beautifully easy, undulating movement and dipping his sharp little black nose daintily in the water? There’s the true poetry of motion for you. Their pelts are worth something, too, and so is their fat. Skunks have their good points, and so have Spaniards. They made it interesting for us yesterday.” Then, after a pause, “I’d hate to have to die in Cuba for fear of being reincarnated as a Spaniard.”

There was some desultory talk, and then O’Neill began, half in jest, half in earnest, to tell of the enterprises he was going to start in Cuba — after the war.

“I’m lucky,” he said. “I can make money anywhere. Anyone could make money here. I tell you, boys, we are going to have a new set of millionaires — Cuban millionaires — and I am going to be one of them. The Klondike fellows won’t be in it.”

But if he had made millions he would have given them away. He was absolutely unselfish, caring for everybody but himself. He looked after the well-being of his troops with almost fatherly solicitude; there was no comfort he could obtain for them that they did not have, and he had the rare faculty of treating them as equals without losing their respect in the smallest degree. When occasion demanded he would rate them in a good-humored, hectoring sort of way that was very efficacious, but he had a dread of even seeming to take advantage of his rank, and it was always as one comrade to another. It rather vexed him to have them present arms or rise to salute him as he passed. “They’re just as good as I am,” he would say. That was not true, but he was modest enough to believe it was. When he jumped from the dock at Baiquiri among grinding, tossing boats, to save the two drowning troopers of the 9th, it was in obedience to a perfectly natural impulse. And he could not understand why any one should make a fuss about it.

O’Neill and I were “bunkies.” Our hammocks were hung together at San Antonio; we had a stateroom together on board the transport when we sailed from Tampa, and after the landing I shared his blankets in the field. I have wakened in the night more than once to find him spreading the whole of the scanty cover over me. When we arrived at Siboney on the night of the 24th, after the fatiguing afternoon march, and camped down on the hard coral road, O’Neill was the most cheerful man in the regiment. He was not going to bother about supper, because the man who usually cooked his ration for him was dead beat: but a sergeant who adored him brought him some coffee, which he insisted I should share.

I honestly didn’t want the coffee or anything else but just to rest, for I was utterly exhausted, and I think there were few men in the regiment who were not. Ten or twelve dropped out by the wayside and came staggering in at intervals through the night. Then it began to rain, and O’Neill must needs drag out a canvas wagon cover — “to keep the bedding from getting wet,” he said. “Don’t imagine it’s on your account, you irritable brute, and stop swearing or I’ll put you under arrest.” Then he crawled in beside me and thrust something deliciously soft under my head — a real pillow! “I’ve got another here,” he said. Knowing him, I had my suspicions, and groping through the darkness I found that his head was resting on a canteen carefully adjusted on a coiled cartridge belt.

As a popular man he had, of course, to have a nickname. The Arizonans called him “Buckie” on account of his having in his unregenerate days “bucked the tiger.” In a very royal and audacious style, leaving the beast scarcely enough sinew to wriggle out of town with. On the muster roll after that fatal fight I read his name among the killed — ” ‘Buckie’ O’Neil, captain.”

His belief in his luck was invincible and he looked on the bright side of everything. One thing he said impressed me at the time: “I have never had a friend go back on me.” I am sure that he spoke the truth. He was a man to inspire loyal friendship. He firmly believed, too, that he would come safely through the campaign. He felt it, he said. This feeling, I think, may be accounted for by the fact that he had so often escaped a violent death at the hands of border outlaws, Indians or Mexicans. Capt. Capron was another who had encountered innumerable perils of the same description, yet he was nearly the first to meet his death. Custom had made both reckless.

I saw O’Neill last an hour before he fell. From Grimes’ battery I was going to the left as Troop A moved up to the right. Once in a while a Spanish shell would drop uncomfortably close, and two or three of the rough riders were already down, wounded by the flying fragments. O’Neill was directing his men to march at intervals of twelve feet. “There will be fewer of you hurt,” he said. We talked a minute or two, and then parted, to meet no more. His first sergeant, himself wounded in the foot, told me the next day how he fell, and twice as he told me he bent his head and hid his face in his arms. “After we left you,” he said, “we went north and then went down a sunken road. It was pretty bad there, but nothing like it was when we got out of it. Then there was an open field, and the bullets from the blockhouse and the trenches in front swept it from end to end. There was a barb-wire fence there, but we beat it down with the butts of our carbines and scrambled through. Then we lay down and fired, but Capt. O’Neill stood up as straight as could be and told us not to get rattled, but to fire steady. Then we made a rush and Troop K came up behind us, and then we lay down again, but Capt. O’Neill walked along the line. Lieut. Kane called to him and says: ‘Get down, O’Neill; there’s no use of your exposing yourself that way.’ Capt. O’Neill turns around an’ looks at him and laughs. You know how he laughed. ‘Ah,’ he says, ‘the Spanish bullet isn’t molded that can kill me.’ Two minutes afterward one struck him in the mouth and he fell dead.”

Rough Rider O'Neill

Latest from History

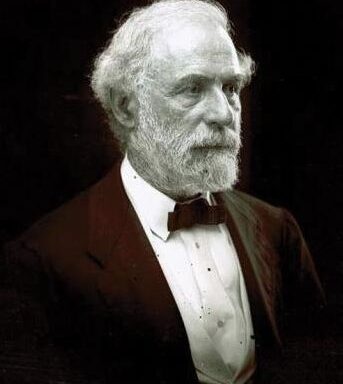

A Memory of Robert E. Lee

"Everyone obeyed him, not because they feared but because they loved him."

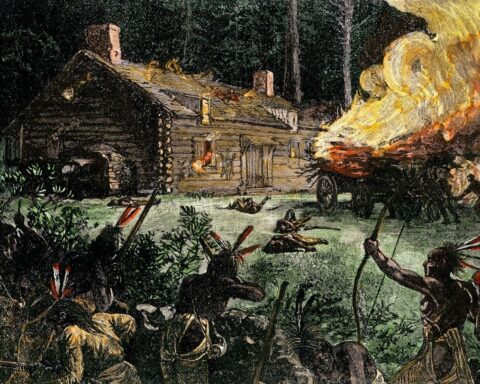

King Philip’s War

In 1675, the number of Indians in New England was roughly computed at fifty thousand souls. They had been supplied with arms by unprincipled traders, which they had learned to use with

The Venerable Bede

"Arising from the gloom of a dark age, he is still considered one of the most illustrious of the learned men of England."

Gildas

The underrated chronicler who paints "fully and vividly the thought and feeling of Britain in the fifty years of peace which preceded her final overthrow."

A Day With a Roman Gentleman

It is a little surprising, considering how accurate is our knowledge of the poetry, philosophy, and art, the wars, religion, and political institutions of the ancients, that we have so vague a