Editor’s note: The following is extracted from A History of Jazz in America, by Barry Ulanov (published 1952).

When the spiritual was transformed into the blues, the content shifted some; the emphasis was less on man’s relation to God and his future in God’s heaven, and more on man’s devilish life on earth. All of the musical antecedents of late nineteenth-century song were summed up, however indirectly, in the blues. The spiritual was the dominant strain, but the work song, the patriotic anthem, minstrel words and melodies, and all the folk and art songs sung in America were compounded into the new form.

There is an interesting parallel to the blues in Byzantine music. Like the Byzantine, the music of the blues has its line of identifiable sources. We can show that Byzantine music derives from Syrian, Hebrew, and Greek sources, but, as scholars have come to understand in the twentieth century, it is essentially an independent musical culture. In the same way we can now understand that the blues is a form complete in itself, whatever its clearly marked origins, especially notable for its balance of intense feeling and detachment. This balance is the distinguishing mark of most of the great blues, of the fine blues singers, and of every sensitive jazz performer since the emergence of the blues.

In the popular song, the evolution of which is at least as long as that of the blues, there is no such balance, and the distinction between form and content is easier to make, since the major concern of popular-song composers and writers has usually been commercial. As one cannot in the blues, one can take for granted the verbal content of the popular song, chiefly a series of approaches to love, happy and unhappy, ecstatic and disastrous, chiefly sentimental, though sometimes, in the hands of rare masters, compassionate.

Most popular songs contain a verse of eight measures, which introduces the working situation, melodically and verbally, and a chorus, which is usually thirty-two measures long. The thirty-two-bar chorus is usually divided into the following simple pattern: the first eight bars state the basic figuration or theme; then these first eight bars are repeated, completing the first half of the song; then follows the eight-bar bridge or release, in which a considerable variation on the theme is effected (here there is usually a change of key, rhythm, and general phrasing); and then in the last eight bars there is a return to the original statement, a recapitulation. All of this adds up to a pattern that can be most easily remembered as A-A-B-A.

The first eight bars of the ordinary thirty-two-bar chorus usually can be broken down into two four-bar phrases in which the second four bars merely repeat the first with a very slight harmonic variation, so that the form can be stated thus: A-A’-A-A’-B-A-A’.

The variations on the basic A-A-B-A pattern of the thirty- two-bar chorus are numerous. There are such obvious but infrequently used variations as the sixteen-bar chorus, usually nothing more than an eight-bar theme and an eight-bar release (A-B); or a twenty-bar chorus (A-B-A); or sometimes a chorus longer than thirty-two bars, as a more complicated content seeks rudimentary form. All of these variations reinforce and redefine the basic thirty-two-bar popular-song chorus.

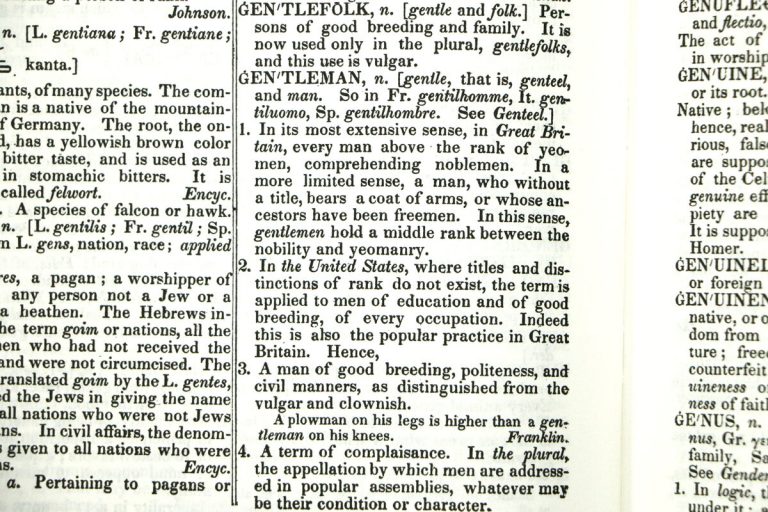

The basic blues form is a twelve-bar chorus, in which an initial four-bar statement is repeated with slight melodic and harmonic changes in the second four bars and then again with more significant variation in the last four bars. The lyric form of this chorus can be compared, as Richard Wright has put it, to a man walking around a chair clockwise (the first four bars), then walking around it again counterclockwise (the next four), and then standing aside and giving a full judgment upon it (the last four bars).

Harmonically the blues follows a simple chord pattern, that of most Western folk music. The first four bars are usually based upon the chord of the tonic (the first note of the scale); the second four bars are usually based upon the chord of the subdominant (the fourth note of the scale); the last four bars are usually based upon the chord of the dominant (the fifth note of the scale).

The blues melody derives from the blues chords, but it has a tonal concept all its own, based on the blues scale, which consists of the ordinary scale plus a flattened third note and a flattened seventh note, which are known as the “blue notes.” Thus, in effect, you have a ten-note scale because both the natural form of the note and its flattened version arc retained in the blues. In the key of C major, for example, the blues scale runs (C—D—E♭—E—F—G—A—B♭—B—C; the flattened third is E flat and the flattened seventh is B flat.

This tonal content causes jazz’s characteristic assault on pitch. From the flattened third and seventh notes of the blues scale, struck against or before or after the natural evaluations of those notes, conies a whole complex of pitch variations. Perhaps the most immediately comprehensible example of what Raymond Scott calls “scooped pitch” can be heard in the playing of alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Johnny does what so many other jazz musicians do, but his meticulous technique makes the practice much more understandable, as he moves from some division of a tone up to a note or by some division of a tone away from it. He may be anywhere from a quarter to say a sixteenth flat in approaching a given note; the same tone divisions may mark his departure from the note, sharpening the note. In the same way jazz singers slide into or away from a note, coming in sharp or flat, departing flat or sharp. The mastery of these musicians and singers is such that they do not produce glissandos, agonized slides over a series of notes, which obliterate all tonal distinctions. For all the apparent casualness, the seeming hit-or-miss nature of their playing or singing, they know what they are doing, and after a while you come to know too.

Most blues melodies use either the first five notes of the ten-note blues scale, or the second five; that is, again using C major as our demonstration key, a blues tune runs from C to F or from G to C (if it runs from C to F the flattened note is E; if from G to C the flattened note is B).

Typical examples of the blues, the best examples with which to start to become accustomed to the curious harmonic and melodic character of this music, “are the records of the early blues singers. It is difficult to get their records today, but some of Bessie Smith’s best sides are or will be available on long-playing records. In “Cold in Hand Blues” and “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon,” you get perfect examples of Bessie’s singing an E flat against an E natural in the accompaniment, or a B flat against a B in the accompaniment; the E flat example is on “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon,” the B flat on “Cold in Hand Blues.” And the two individual sides also illustrate the characteristic limited melodic range of the blues; “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon” is built on the first five notes of C major, “Cold in Hand Blues” on the second five. (Incidentally, on these sides you get the additional pleasure of listening to Louis Armstrong in 1925 when he was still playing cornet and was at the peak of his early style.)

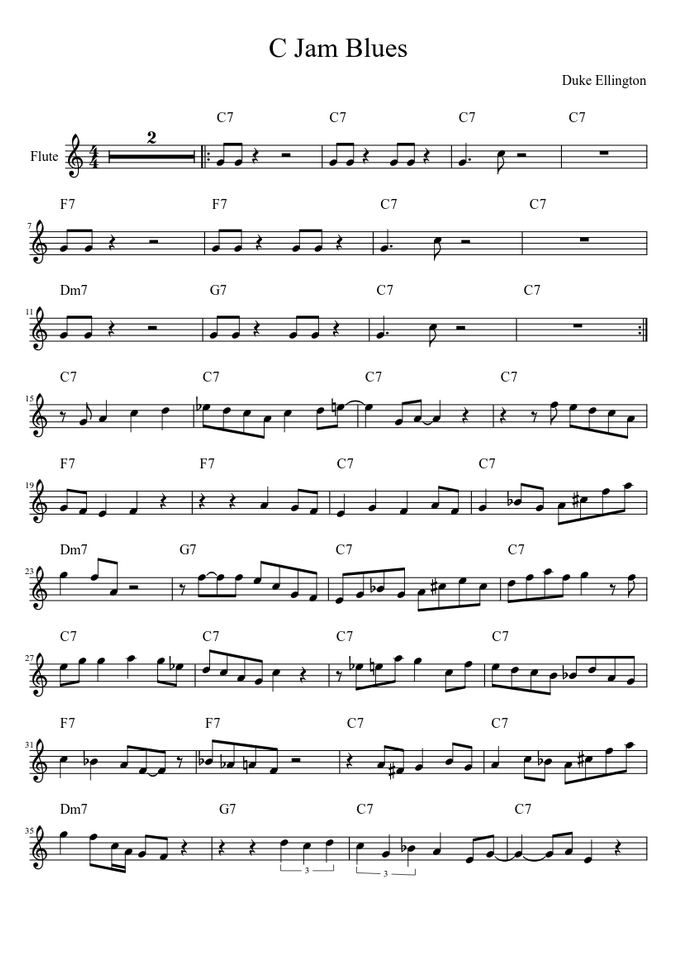

Variations in the blues form are possible, both in its chord structure and in melodic line. Passing tones (tones out of the immediate harmony, not in the chords at hand) can be used to supplement the five fundamental notes of either half of the blues scale, as the ornaments of a melody or as integral parts of it. Instead of following the conventional division of the twelve bars of the blues into three repetitious four-bar segments or phrases, each division of four bars may vary considerably from the preceding phrase. The blues may be broken up into two-bar instead of four-bar phrases, so that in one blues chorus there will be six phrases instead of three. You may get two-bar phrases with two-bar fill-ins, as in Duke Ellington’s “Jack the Bear,” where the piano plays the essential two-bar phrase and the band plays the two-bar fill-in.

From the two- and four-bar phrases of the blues came the riff, which was the outstanding instrumental device of the so-called swing era. The riff is a two- or four-bar phrase repeated with very little melodic variation and almost no harmonic change over the course of any number of blues choruses.

Blues melodies are often exquisitely simple. In Ellington’s “C Jam Blues” the four-bar main phrase consists of only two notes, G and C. The first two bars (or riff) are all on G; in the third bar the C is introduced in a slurred pair of eighth-notes. “C Jam Blues” is worth careful listening, to hear how ingeniously this seemingly empty pair of notes becomes a fresh, swinging blues.

Generally the blues bass is played in unaccented four-quarter time, the best example of which is the “walking bass.” If you listen carefully to the Ellington recording of “C Jam Blues,” you will hear a definitive example of the walking bass — 1 2 3 4 / 1 2 3 4/ 1 2 3 4, over and over again, with brilliant chord or key changes to make room for the progression from tonic chord to subdominant to dominant, from C to F to G seventh over a series of scale-like phrases. Another very effective bass for the blues is the rolling octave bass, which consists of dotted eighths and sixteenths, syncopating up and down octaves.

“Stride piano,” the particular pride and joy of Fats Waller and, before him, of innumerable ragtime pianists, comes from the blues. The trick in the stride bass is to play a single note for the first and third beats of the bar, and a three- or four-note chord on the second and fourth beats. The effect when the stride bass is poorly played is plodding and corny; but when this kind of piano is played by a Fats Waller or an Art Tatum the result is exhilarating.

The blues is usually played in unaccented four/four time or with stride accents, but it does, in one of its most prominent variations, make a departure from this structure. The variation? Boogie-woogie, of course. Boogie-woogie, contrary to the general impression, is merely a piano blues form which on occasion has been adapted for orchestral use. It goes back to ragtime and hasn’t changed very much since its first appearance. It represents nothing more than a jazz conversion of the traditional basso ostinato device, the pedal-point or organ-point reiteration of a basic bass line. In boogie-woogie eight beats to the bar are usually emphasized, with single notes or triplets, following the fundamental harmony of the twelve-bar blues form. More conservative than most blues performers, boogie-woogie pianists almost never depart from the original key and usually play in the key of C. Cleverly orchestrated, the obstinate bass suggests the classical passacaglia form. As boogie-woogie is most often played, by such broad-beamed performers as Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson and Meade Lux Lewis, it is confined in its ornament to trills and tremolos in the right hand, and constricted rhythmically and harmonically.

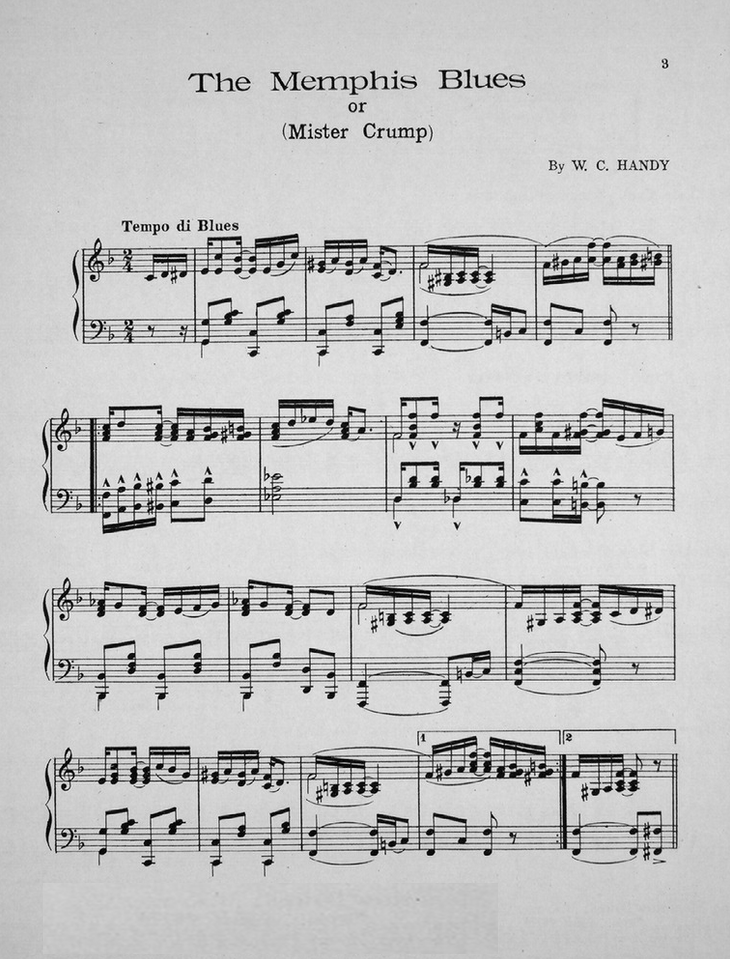

Although the blues is the base, harmonically, melodically, and even to a degree rhythmically, of jazz as we know it today, it did not appear on paper under its proper name until 1912. Jazz was on the threshold of its formative years as an art and of its widespread recognition. It was given a considerable push on its way in the first published blues, W. C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues,” written originally as a campaign song for E. H. Crump, a mayoralty candidate in Memphis in 1909. Though Crump was a reform candidate, William Christopher Handy’s “Mister Crump” certainly didn’t indicate that; the words were, if anything, a mockery of the candidate’s reform promises:

Mister Crump won’t ‘low no easy riders here;

Mister Crump won’t ‘low no easy riders here;

I don’t care what Mister Crump won’t ‘low,

I’m gonna bar’l-house anyhow;

Mister Crump can go an’ catch himself some air!

“Easy rider” meant, and still does, a lover or pimp who hangs on to his woman parasitically; “barrelhouse” is a rough saloon, literally a house where barrels of liquor are tipped on end; used as a verb, it indicates spending a rough evening or day or life, or as here the music that reflects all of that. The tune written for these words in a sixteen-bar form a cross between the blues and the popular song choruses but essentially the former became the “Memphis Blues” in 1912. In 1914 Handy published his “St. Louis Blues” with its provocative Tangana rhythm, which is a kind of habanera or tango beat consisting of a dotted quarter, an eighth-note, and two quarter-notes.

All of these the adroit balance of feeling and detachment in words and music, the formulation of a distinctive melodic line based on its own tonal concept, pliability as instrumental and vocal music show why the blues has been the most enduring and persuasive of jazz forms.

Contrary to the average conception of the form, the blues claims all creation as its subject, ranging impressively from Mississippi floods to New Orleans maisons to the WPA and war and peace and other problems. But the blues is not only a music for melancholia. There is great joy in the blues too, a joy that sometimes retains a strain of nostalgia or carries a thread of yearning for money, for romance, for the moon. The joy is still there, however, and so too is the great cry that identifies these songs as songs of the times. Floods and floozies, unrequited love and unemployment, the blues describes them all.

The twelve-bar form we know as the blues came into its vigorous own in the early years of this century. Up and down the Mississippi though its major sources were in New Orleans the blues was sung and played by the Negro musicians of 1910 and 1920 and 1930. To white America, in showboats, in New Orleans and Chicago and New York night clubs, the Negroes brought their tales of weal and woe.

The blues was the base of the early great recordings of Louis Armstrong, whose trumpeting genius formed, in turn, the base for most of the hot jazz that came afterward. His early records are magnificent examples of the blues and the vitality of its composers and lyricists and performers. Unlettered, morally but not musically undisciplined, the wild musicians of Louis’s, Kid Ory’s, and King Oliver’s bands created great jazz, great music “Gully Low Blues,” “Wild Man Blues,” “Potato Head Blues” out of the happy chaos of the New Orleans Negro quarter before and during and after World War I. These blues tell you much about the life and times of the fabulous men who made that music.

The chronicle of the blues goes on through the great singers: the five Smiths Bessie, Clara, Trixie, Mamie, and Laura; Ida Cox, Chippie Hill, Ma Rainey. This impassioned history gives you rough, untrained voices with a majesty and a power that have scarcely been equaled by the finest of Wagnerian singers. These women were sometimes impoverished, rarely comfortable financially. They sang for gin and rent money, and their masterpieces appeared on the so-called “race” labels of the record companies. Their records were thus bought mainly by their own people, and few of these singers reached the tiny affluence which would have given them a fair life. Only Bessie Smith scored financial success, largely because Frank Walker, then Columbia Records’ race record director, saved her money for her.

At first you may dislike the harshness of Bessie’s voice and of the voices of the other Smiths and Ma Rainey. You may be put off by the sometimes monotonous melodies. But, if you listen carefully, you will find a richness of vocal sound and of verbal meaning too. You will discover a touching stoicism in the face of disaster, touching because there are fear and sorrow in the laments of Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey, and passion as well but all laughed or shouted away. And in the laughter and the holler you may discern the wisdom of the Southern poor Negro or white which puts the facts of nature in their proper place, which refuses to be overwhelmed by physical or mental torture. One feels these things, the blues singer says, but one can do nothing about them. And so she communicates the torture, but always with philosophical detachment. This is a vigorous and vital music; it calls a spade a spade, a flood a flood, and unemployment an unpicturesque evil. Along with spades, floods, and unemployment the sexual relations of man and woman are seen as both glorious and inglorious.

The rewards of fealty to the blues have come slowly. W. C. Handy, who wrote the enduring “Memphis Blues” and “St. Louis Blues,” was not well off until his near-blind old age, when the stream of royalties from those blues classics began to flow in. Billie Holiday, perhaps the greatest of present-day blues singers, is a moderate night-club success, singing in the boxes and holes and caverns of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, and Hollywood. Billie’s trueness to the blues is a cornerstone of her greatness. While she sings a pop tune with artistry, shaping a shabby phrase so it gleams as it never did before, she does just as well in the blues, in the basic jazz songs, which she sings with unmistakable conviction. “Fine and Mellow” and “Billie’s Blues” are among her best songs, along with the evergreens of jazz, such fine songs as “The Man I Love,” “Body and Soul,” “Them There Eyes,” and “Porgy.”

The people who like the way Billie and other blues singers sing will follow them wherever they go, to after-hours joints in Harlem, to squalid little clubs in downtown New York, where the liquor tastes like varnish, where the prices, unlike the decor, are right out of the Waldorf and El Morocco.

Few other singers combine the attractions of Billie Holiday, who is not only a singer with a sumptuous style, but also a remarkably beautiful woman. There are other brilliant blues singers. There is Big Joe Turner, a fabulous fellow from Kansas City, who matches the stature of the men he shouts about in the blues. There is Jimmy Rushing, Count Basic’s singer. It was his barrelhouse figure that inspired the song “Mr. Five by Five.” Jimmy knows a thousand old and new blues, to which he has added countless variations of his own. One of the best of these is “Baby, Don’t Tell on Me”:

Catch me stealin’, Baby, don’t you tell on me,

If you catch me stealin’, Baby, don’t you tell on me,

I’ll be stealin’ back to my old-time used-to-be.

Thought I would write her, but I b’lieve I’ll telephone,

Thought I would write her, but I b’lieve I’ll telephone,

If I don’t do no better, Baby, look for your daddy home.

He ends the blues with the amusing line, “Anybody ask you who was it sang this song, tell ’em little Jimmy Rushing, he been here and gone.”

Jack Teagarden, a big burly Texan with an infectious Panhandle accent in his singing, has always been associated with the blues. One of the few white men to attain distinction in the form, he lapses into the twelve-bar chorus of the blues as a matter of course. He is identified irrevocably with W. C. Handy’s “Beale Street Blues” and the lovely “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,” which was the theme song of his big band of short but often distinguished life. He improvises beautifully with his trombone or his delicate baritone voice, making up words to ungainly measures when that is necessary, culling his rolling blues phrases from the cowhand. Such effective syllabifications as “mam-o” for mamma,”fi-o” for fire, and “Fath-o” for Paul Whiteman (known to his familiars as Pops or Father) are Teagardenisms. Coming late to an engagement one night, he jumped onto the bandstand, where his orchestra was already playing. Noting the severe expression on the face of the manager of the place, he improvised this blues:

Comin’ through the Palisades I los’ my way;

Comin’ through the Palisades I los’ my way;

Thought I was back on the road, workin’ for MCA.

Jack’s plaint is at a large remove from the vital central themes of the blues, but it indicates clearly how much a part of jazz the form had become by the late thirties. It was the blues that the instrumentalists played and the singers shouted and wheedled that sent jazz around the United States and across the world. It was the blues that Louie Armstrong played so persuasively and Bessie Smith sang so movingly that served jazz so well when it came to its Diaspora. There was, after all, something to disperse.