James Smith, The Voyage and Shipwreck of Saint Paul (1880)

Part of a series of history books that belong in every American’s library. Recommendations welcome.

Smith’s Voyage and Shipwreck of Saint Paul is considered a Christian classic and one of the finest expositions of the latter part of the Acts of the Apostles ever written. Its research underlies much of FF Bruce’s classic commentary on that book. And yet it is not really a bible study at all. Rather, it is the study of one particular first-century nautical voyage that happens to be recorded in the Bible.

Smith, a long-time sailor as well as a scholar of classical languages, examines everything we know about first century Roman shipping and the geology and weather of the Mediterranean. He then applies it to Luke’s description of the voyage that resulted in Paul being shipwrecked on Malta. In addition to narrating the voyage itself, Smith includes dissertations on the ships of the ancients, the trade winds and typhoons of the Mediterranean, and the geology of Malta and that particular inlet known as “St. Paul’s Bay.” His appendices include extracts from the journals of other ships that have met the same fate as Paul’s, including a sailor aboard the yacht St. Ursula, which sank with three other ships in a Mediterranean storm in 1856. He also includes explanations of the specific navigational terms used by Luke. The result is a timeless reference work that explains far more than a biblical passage. It relates nearly everything we know about shipping in the early empire period of Rome.

Smith begins with a short dissertation on the writings of St. Luke, the traditional author of both the Acts and third gospel. He paints a short biographical picture of the first century doctor, based not only on hints from Paul’s writings but from the traditions recorded by the ante-Nicene fathers. However, Smith adds one assertion that none of those sources mentions: that Luke, before joining in Paul’s journeys, must have spent at least some of his time aboard ship.

“No man could by any possibility attain so complete a command of nautical language who had not spent a considerable portion of his life at sea.”

— James Smith on St. Luke

It is, Smith argues, Luke’s command of specific nautical terms that allows us to understand many of the decisions made by the crew of Paul’s ship, decisions that Luke does not explain in any detail. Luke may not have known the reasons in any case, for as Smith asserts, Luke spent his time on the seas “not … as a seaman, for his language, although accurate, is not professional.” But it is the accuracy of his observations and his care in recording them that makes it possible for Smith to undertake such a study.

The narrative of the voyage itself is broken into five sections, corresponding roughly with the five stops the ship (or rather ships, as Paul travels in three) makes on the journey from Caesarea to Italy. There is the first journey, lasting only a few days, with a short stopover at the port of Sidon and thence to Myra of Lycia. Smith takes the opportunity to introduce the basic nautical terms used by Luke, as well as to explore the writings of Strabo, whose work Geography provides much of our knowledge of the area during that time. From there Luke, Paul, and the Roman soldiers accompanying them catch a ride on an Alexandrian ship, one of the floating granaries that carried the annual harvest from Egypt to Rome. It is from this point that they leave Asia behind, hoping to ride favorable winds westward across the Aegean Sea.

The second section narrates the difficulty this entails, as though the journey of 130 miles to Cnidus (at the entrance of the Aegean Sea) could have been made in a day or two with cooperative weather, the journey progresses slowly and with much difficulty because the winds remained contrary. Based on the ship’s change in course from a normal trip straight to Italy to Fair Havens on Crete, Smith concludes that the winds were generally from the northwest, which, he explains, “is precisely the wind which might have been expected in those seas toward the end of summer.” The sailors certainly expected such a change in course as possible even as they hoped for better weather, for they without difficulty pass under the lee of Crete and land near Nacea on that island. Smith takes here the opportunity to recount several other historical journeys (from 1582 and 1798) which encountered precisely the same winds and as a result, pursued precisely the same course laid out by Luke.

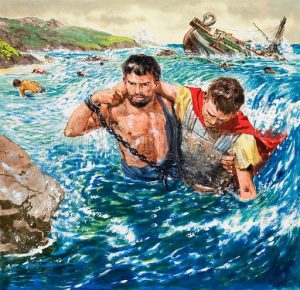

The third section, from Crete to Malta, contains the gale that resulted in the ship being almost a total loss. Choosing to shoot for Phenice – 34 miles away on the same island and a far better winter port – the ship leaves under fair winds which immediately change and rise. Even though they are remaining as close to the island as the large ship can manage, it is soon obvious that they will not be able to turn into the wind to make land. Instead they are driven before the wind past the small, portless island of Clauda and into the open sea.

The typhonic wind drives them for a full two weeks. Luke explains (and then Smith explains the history and importance of) various measures taken by the crew. They undergird the ship with cables to hold it together. They lighten the ship by throwing such tackle as is unnecessary overboard. Without the stars to tell them where they are – and with the kitchen flooded wherein which they might prepare a meal – a sense of hopelessness arises in the crew. They must hope and pray that they can find an island to run into, or else despite their best efforts the ship will likely founder and sink.

Smith all this time is including interviews with sailors who have been in such storms, explaining the options the sailors were forced to choose from: “I have already assigned my reasons,” he explains in one example, “for supposing that the ship must have been laid on a starboard tack under the lee of Clauda, for it was only on this tack that it possible to avoid being driven on the African coast.”

The sailor’s love of the sea comes through in every passage. One can almost feel that he is standing in the gale itself, arguing whether it is best to fly the storm sail and thus wrestle the storm, or pull all the gear down and entrust himself wholly to the wind. Smith illustrates that the sailors did everything according to Hoyle, or in this case, according to traditions followed even under French maritime law. He includes a parallel reading of one section of Acts alongside the 1672 French work Us et Coutumes de la Mer (Custom and Habits of the Sea). Unfortunately the passages are in French and I can’t read a word of them.

In the fourth section, the men on the ship hear land nearby – waves crashing on enormous breakers. As it is still dark they throw every remaining anchor into the sea, hoping the hold the ship in place until the sun can rise and they can pick a suitable creek into which to drive it. They steer the ship ashore in Saint Paul’s Bay on Malta where they will spend the rest of the winter. Smith here recounts the nautical terms used by Luke at the end of the journey, explains the specific method of beaching a sailing ship (with historical examples), and recounts the terrifying minute (for Paul anyway) where the Romans attempt to execute the prisoners lest they escape when everyone abandons ship. The Centurion, however, overrides custom, and all 476 men aboard scramble safely ashore.

The final section recounts the short journey from Malta to Italy, made on a new ship – the journey’s third – called the Castor and Pollux. The journey is uneventful, Paul arrives in Rome, and Luke brings his Acts to an end. Smith brings his major story to a close here, only to go on to smaller dissertations like On the Wind Euroclydon, On the Island Melita, On the ships of the Ancients, and On the Geological Changes in St. Paul’s Bay, each of which gives depth to some part of the main work, even while its absence from the main work allowed the story to continue unhindered.

Smith has created a timeless work, demonstrated by the fact that it is still in print after nearly a century and a half. His writing is clear and present – even while he’s off on a tangent the reader never loses the feeling of urgency of the situation Paul and Luke are experiencing. For students of the Acts, or of the life of the Apostle Paul, it is an invaluable volume.