Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twenty-sixth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXVI

Owing to the delay caused by the attack on and pursuit of the impi from the Umguza, as I have just narrated, Colonel Spreckley’s patrol did not leave Bulawayo for Shiloh until the afternoon of the following day, Sunday, 7th June. This patrol comprised about 330 white men, about half of whom were mounted, 100 Colonial Boys, and 100 Friendly Matabele—over 500 men altogether.

As we did not proceed along the main road, but first took a branch track to the old Imbezu kraal, and then followed the course of the Kotki river until we struck the main road, we did not reach the site of the old police camp near Shiloh mission station until Thursday, 11th June. Up to this time we had not seen a single native, whilst all the kraals we passed had been long deserted and all stores of grain removed, so that our horses and mules, having to depend entirely on the dry scanty grass for their sustenance, lost condition rapidly.

One day we outspanned close to a miner’s camp, which was situated on a rise above the Kotki river, and as I was field officer for the day and had to post the videttes, I placed two of them on the site of the mining camp. Here we found the dead bodies of three natives, who proved to be Zambesi boys who had been working at the mine at the time when the rebellion broke out. On inquiry I found that this camp had belonged to an American miner named Jack Stuart—a lieutenant in Grey’s Scouts—from whom I learned, that on hearing rumours towards the end of March that a native rising was imminent, he and his partner had gone in to Bulawayo to ascertain if there was any truth in the report. Six Zambesi boys were left working in the shaft, which had been sunk on a reef just alongside of the camp, and two days later one of these boys came to town and reported that on the previous evening a party of Matabele had visited the mine, and forthwith proceeded to murder all the Zambesi boys they found there. He himself, he said, had managed to escape by running, but he thought that all his companions had been killed. A few days later, however, another of these boys turned up who had been very badly wounded and left for dead by the Matabele.

It appears that, on seeing two of his friends attacked, this boy had made a bolt for it, but was overtaken and knocked down by a heavy blow on the back of the head from a knob-kerry. He fell on his face stunned, and was then stabbed in the back with an assegai, the weapon being driven clean through him, and then twice nearly but not quite withdrawn from the wound, and again driven through him, so that, although there was only one wound on his back, there were three in front, where the point of the assegai had come through, just below his breast-bone, and his right lung must have been punctured in three different places. This boy would seem to have lain a day and a night, insensible, where he fell, but on regaining consciousness had found strength enough to walk to Bulawayo, some twenty miles distant from the mining camp where he had been knocked down, assegaied, and left for dead.

On his arrival in town he was at once taken to the hospital, and, owing to the kind nursing and skilful treatment which he received there, he in a few weeks’ time completely recovered, and although he still bears the scars of the wounds which he received, his general health appears to be as good as ever it was.

On Friday, 12th June, the day after our arrival on the site of the old police camp, a fort was built, and here Native Commissioner Lanning was left in charge with a garrison of about seventy white men and twenty Friendly Matabele and a stock of provisions sufficient to last for two months.

On the following morning we struck across country towards the Queen’s Mine, a property belonging to Willoughby’s Consolidated Company. That night we slept on the way there, and the fresh tracks of Kafirs and cattle having been seen late in the afternoon, a patrol was sent after them very early the next morning, the column shortly afterwards getting under way and arriving at the mining camp at about eight o’clock.

Here it was found that although a good deal of property had been destroyed by the Kafirs, but little damage had been done to the machinery and pumping gear, the savages probably not having recognised its value nor been sufficiently energetic to give themselves the trouble of smashing it up. Another short trek in the afternoon brought us to the ford of the Impembisi river, on the main road between Bulawayo and the mission station of Inyati. Here the patrol which had left us in the early morning under Captain Gradwell rejoined us just at dusk, having been unsuccessful in coming up with any Kafirs or cattle, all of whom seemed to have gone down the Impembisi river.

As the mules and horses were now getting into very low condition, it was determined not to take the whole column on to Inyati, but only to send on the contingent who were to remain in garrison there under the command of Lieutenant Banks-Wright, together with another 100 men who were to return to the main column as soon as the fort was in a fair way towards completion. This force was accompanied by four waggons carrying provisions and other necessaries for the garrison of the fort, and the Rev. Mr. Rees also went with it, in order to bury the remains of the six white men who had been murdered near the police camp of Inyati on 27th March.

Five of these bodies were found lying on the roadside near together, about a mile on this side of the police camp, while the sixth was discovered near the camp itself. The corpses had been partially mummified by the dryness of the atmosphere, and were all quite recognisable. Mr. Graham, the native commissioner, and his four companions had evidently been attacked by a large force of Kafirs soon after they had left the police station, and were killed whilst defending the waggon on which they were travelling to Bulawayo. In addition to their bodies the remains of two Colonial Boys were also found who had been murdered at the same time as their white masters.

That Mr. Graham and his companions had made a good fight of it, and sold their lives dearly, was evident from the number of empty cartridge-cases which were found on the ground round their dead bodies, Lieutenant Howard having picked up and counted eighty-five. As, however, the Matabele had removed their dead, it is quite impossible to say what loss they had suffered. The murdered men were all buried with military honours in the cemetery near the old mission station by Mr. Rees. This gentleman himself, with his wife and family, must have had a very narrow escape, as they only left the mission station on the 26th March, the day before Mr. Graham and his companions were attacked and killed; and they must too have only just passed through the Elibaini Hills on their way to Bulawayo before the rebels collected there. Both mission houses at Inyati were found to have been burnt down and destroyed, as well as the church, in which it was evident that large quantities of wood had been piled up in order to set light to the heavy beams supporting the roof. The natives had also taken the trouble to chop down fruit trees and ornamental shrubs growing round the mission houses, and had evidently done their best, not only to rid themselves of the presence of all white men in the country, but also to destroy as far as possible all traces of their ever having been there.

On Wednesday morning the men who had been sent to assist in building the fort at Inyati returned to the Impembisi, and in the afternoon the whole column moved some four miles up the river to Mr. Fynn’s farm. On the morning of the same day Lieutenant Mullins—Mr. Colenbrander’s brother-in-law—had been sent on to this point with some fifty Colonial Boys to look for grain, and had come across a considerable number of armed Kafirs in a very broken, densely-wooded piece of country, just to the east of the Impembisi river. As it was impossible for Lieutenant Mullins to tell the numbers of the rebels in the broken country, he retired with his Colonial Boys to the top of a single hill to the west of the river, and sent back to camp for reinforcements. Captain Grey was at once sent on with his Scouts, and the whole column followed more leisurely, arriving at Fynn’s farm just before sundown.

Captain Grey had seen a considerable number of natives, evidently watching his men from the tops of different kopjes, but as the country they were in was altogether impracticable for horses, he was unable to attack them, and they on their side showed no disposition to come out of the hills. At a council of war that evening it was determined to endeavour to clear the hills in the morning with as large a force of footmen as could be spared from the laager; Grey’s Scouts at the same time being sent round at the back of the hills in order to cut off any Kafirs who might be driven out of them into the level country beyond. The general impression in camp was that the Kafirs were in force, and that we should have all our work cut out to drive them out of their positions. And so we should have had, if they had only remained to dispute our advance. However, leaving the laager on the following morning just as day was breaking, we entered the hills at sunrise, and went right through them without seeing a sign of the rebels, who we found had decamped during the night and fled to what they considered a more secure stronghold—to wit, the “Intabas a Mambo,” a sort of miniature Matopos some twenty miles farther eastward.

To this fastness it was not possible for Colonel Spreckley to follow them, so, as we met no other natives during our farther progress up the river to Mr. Arthur Rhodes’ homestead, nor on our return journey from there to Bulawayo, we had absolutely no fighting during the whole trip.

Curiously enough, the temporary huts in which Mr. Fynn had been living before the outbreak of the insurrection had not been burnt, and on going up to a kraal some few miles higher up the river, where had dwelt a native to whom he had entrusted some Merino sheep, pigs, and a number of very handsome black Spanish fowls, Mr. Fynn found the fowls and pigs still there and in very good condition, and on making a closer examination observed fresh Kafir footprints, and therefore came to the conclusion that the man he had left in charge of his live stock was still looking after it, retiring into the hills by day and feeding his master’s pigs and fowls by night. Mr. Fynn therefore asked Colonel Spreckley to allow him to take two friends that evening, and return to the kraal in the hope of being able to intercept his servant, and bring him down to the camp.

The plan succeeded perfectly, for just after dusk the man came along the footpath leading from the river to the kraal, and was suddenly confronted by Mr. Fynn, who had been waiting for him concealed behind a bush. The Kafir was at first very much taken aback, but when he recognised his master, he burst out laughing and said: “Why, is it you, Willy? you’ve caught me now.” This man was a native of Delagoa Bay, and being lame had been able to escape being forced into taking part in the rebellion, and ever since the outbreak had been able to surreptitiously look after a portion of his master’s property, for though the Merino sheep had been driven off to the “Intabas a Mambo,” the pigs and fowls had been left, and these the faithful servant had fed and watered regularly every night.

He was able to give us a great deal of useful information, and told us that the men who had been seen the day before amongst the hills on the other side of the Impembisi river were a portion of the impi which had suffered so heavily at the Umguza, on Saturday, 6th June. He informed us that they were thoroughly disheartened, and wished to surrender, but were afraid to do so, knowing that they had made the white men very angry by murdering their women and children. He gave the names of thirteen headmen of kraals who had been killed on that fatal day, all of whom had been personally known to Mr. Fynn, as they had been one and all living on Mr. Arthur Rhodes’ block of farms before the rebellion broke out.

The next three days were spent in collecting grain, an immense amount being found stored in all the kraals on Mr. Arthur Rhodes’ farms. In almost every kraal was found something or other which had been taken from his homestead, which had evidently been completely looted before it was burnt down. Several hundred head of cattle were also recovered which had been stolen from Mr. Rhodes, but the rinderpest was amongst them and they died by the score every day. As it was very important to get as much corn as possible to Bulawayo for the use of the horses and mules stabled there, and it could not be all carried in at once on the waggons at Colonel Spreckley’s disposal, a large amount was stored in a kraal near Mr. Fynn’s dwelling-house, and Captain Robinson with fifty men and some Friendly Matabele left in charge of it until it could be sent for.

When this matter had been arranged, the column moved up to Mr. Arthur Rhodes’ desolated homestead, which was reached at mid-day on Sunday, 21st June, and leaving again the same evening arrived in Bulawayo two days later after an absence of seventeen days.

On our arrival in town we heard for the first time of the insurrection which had broken out in Mashunaland, and learned the sad news that many settlers had been murdered in the outlying districts of the country. Colonel Beal was at this time already on his way back to Salisbury with the entire force under his command, and two days after our return to Bulawayo sixty more mounted men of Grey’s Scouts and Gifford’s Horse, under the command of Captain the Hon. C. White, were despatched to the assistance of their fellow-colonists in Eastern Rhodesia.

When the secret history of the rebellion in Mashunaland comes to be known, I fancy it will be found that it was brought about by the leaders of the Matabele insurrection through the instrumentality of the Umlimos or prophets, who exist amongst all the tribes in Mashunaland, where they are known as “Mondoros,” i.e. “Lions.” In the district to the north-west of Salisbury there lives a prophetess known as “Salugazana,” whose magical powers were apparently believed in by Lo Bengula, as he was in the habit of sending messengers to consult with her.

Now, we know that messages have been sent to this wise woman either by the leaders of the Matabele or the agents of one of the Umlimos or priests during the present rebellion, and I think that she was in all probability informed that the white men had all been killed in Matabeleland, including the column under Colonel Beal, and asked to disseminate this news amongst all the members of the priestly families throughout the country, bidding them at the same time to call upon the people to destroy the few surviving white men still left alive in the eastern province of Rhodesia.

As for the rising in Mashunaland proving that the natives of that country have been very cruelly treated by the whites, as Mr. Labouchere has asserted, it really demonstrates nothing of the kind; it only shows that the Mashunas imagined that they would be able to possess themselves of a vast amount of valuable loot with little danger to themselves, and no fear of punishment. The kindness or otherwise of the government of the whites would not be likely to weigh with them one way or the other, given the belief in their own power to kill the whites and take possession of their property without fear of retribution.

That is the crux of the whole question; for no one who has lived long amongst the various peoples generically known as Mashunas, whose principal characteristics are avarice, cowardice, and a complete callousness to the sufferings of others, will be inclined to doubt that were they governed by an angel from heaven, they would infallibly kill that angel, if his wing feathers were of any value to them, provided that they believed at the same time that the crime might be committed with impunity.

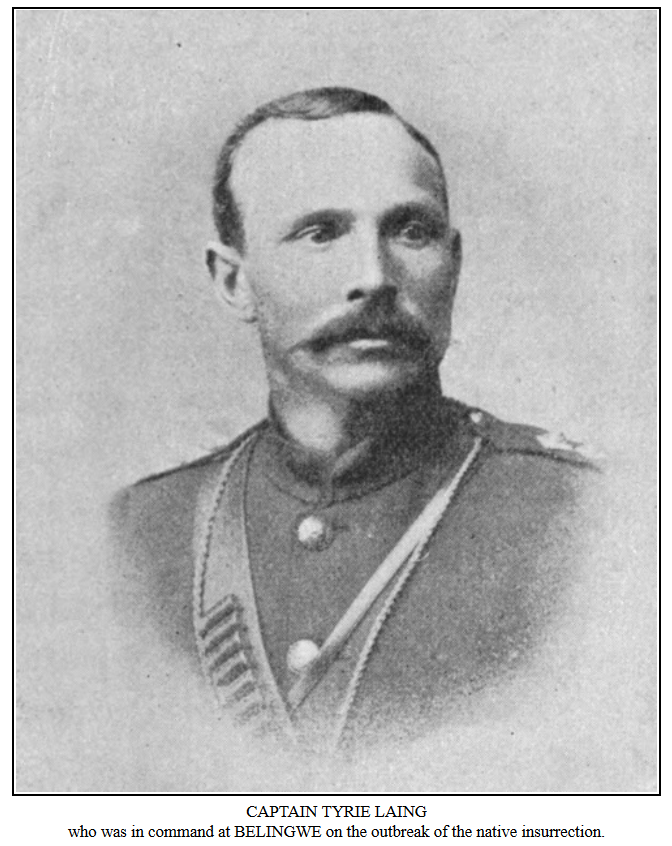

Towards the end of June Captain Laing arrived in Bulawayo in command of the relief forces which had been sent to him from Tuli and Victoria, Lieutenant Stoddart being left in command of the laager at Belingwe. On his way to Bulawayo, Captain Laing had had several successful engagements with the tribes in rebellion living between Belingwe and Filibusi, who are all Mashunas, with a small number of Matabele living amongst them; these latter having been the ringleaders of the rebellion in this part of the country. Captain Laing received very valuable assistance from Matibi, a Mashuna chief living near the Bubyi river, who sent several hundred of his men to accompany him on his march to Bulawayo. These men did good service and fought well when supported by white men. They accompanied the column as far as the Umzingwani river, twenty-five miles from Bulawayo, returning home from this point loaded up with loot of all kinds which they had taken from their rebel countrymen.

Besides Matibi, it is worthy of remark that Chibi and Chilimanzi, the two most important chiefs in the district between Belingwe and Victoria, have both not only held aloof from the present rebellion, but have given active assistance to the whites since the outbreak of hostilities, whilst Gutu’s people—the Zinjanja—have also remained loyal to the Government.

I have now, I think, given a fairly comprehensive history of the late insurrection in Matabeleland up to the time when, relief forces having arrived in the country, it was deemed expedient to disband the volunteer troops which had been originally raised to suppress the rebellion, and I will therefore leave to abler and more accustomed pens than mine the task of describing all the subsequent incidents of a campaign which we will hope is now fast drawing to an end. I will only say that no one appreciates more than myself the excessive difficulties that have been encountered in dislodging the rebels from such fastnesses as the Intabas a Mambo and the Matopo Hills, or recognises more fully the brave work which has been done under the guidance of Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington, by Colonel Plumer, Major Baden Powell, and all the officers and men under their command.

The Bulawayo Field Force was not actually disbanded until Saturday, 4th July, upon which occasion the assembled troops were addressed by Lord Grey after they had been first inspected by Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington. The Administrator concluded his address to the members of the force in the following words:—

“All of you have acquitted yourselves as brave men, and I would particularly commend the conduct of Colonel Napier, who throughout the campaign has performed his very arduous duties so satisfactorily. But mingled with our enjoyment there must be some pain in looking back upon many of the episodes of this rebellion. The Company has done its best to look after your comfort, but you have undergone notwithstanding some severe hardships, which, however, you have borne like men; and the only complaint I have heard is that you were not always able to go out against the enemy, but had to perform as well the hard and monotonous work of laager and fort duty. Many of you have a Matabele memento in the shape of a wound, the mark of which you will carry to your graves. Many too have lost friends; and possibly none of us realise the loss of life which has taken place both before and during hostilities; for our losses have been heavy, and form a large percentage of the total number of people who were engaged in the exploitation of the country. I cannot refer to individual cases of bravery where all have done so well, but I would again especially mention Colonel Napier’s services to the country. He has exhibited remarkable tact and judgment, and has freely given great assistance to the Government. I regret that he is to-day retiring from the service, but I hope that he will continue to give us the benefit of his experience. I do not like to mention any particular troop, as each has acted so creditably, but I would note the excellent services rendered by the Africander Corps in this war, as showing the whole world the complete brotherhood which exists between the two races of Dutchmen and Britons in Rhodesia. I trust that an Africander troop will again form part of the new force which is now being raised by the Government. Information reached this country by last mail that Her Majesty has been pleased to allow a medal to be worn for the last Matabele war, and I shall represent strongly to Her Majesty that the same honour ought to be conferred on the members of the Bulawayo Field Force. You have as much right and title to the distinction as those who fought in the first war, and I hope there will be a sufficient number struck for both those who fought in the first war and those who have fought during the present rebellion. I thank you for your assistance in the past, and I hope you will remain in the country to witness the prosperity which is certain to come.”

___________________________________________________________

And now, Lord Grey’s speech to the members of the Bulawayo Field Force having formed the closing scene in the history of the corps, whose deeds in the cause of civilisation, and for the preservation of British supremacy in Rhodesia, it has been my endeavour to describe in the foregoing pages, it only remains for me to bid adieu to my readers, and to hope that the intrinsic interest of the scenes I have attempted to describe in very plain and homely fashion may be sufficient to atone for the deficiencies which will doubtless be only too apparent in my literary style.