Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Beneath the Banner: Being Narratives of Noble Lives and Brave Deeds, by F.J. Cross (published 1895)

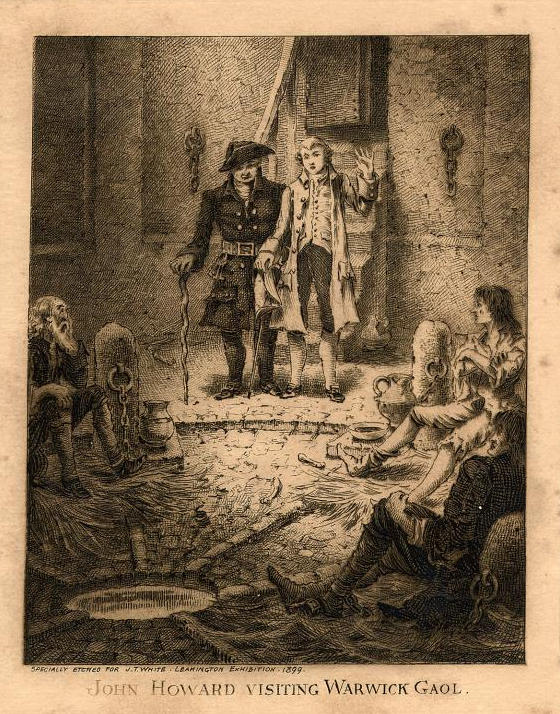

In St. Paul’s Cathedral there stands a monument representing a man with a key in his right hand and a scroll in his left, whilst on the pedestal from which he looks down are pictured relics of the prison life of the past. The man is John Howard, who traveled tens of thousands of miles, and spent many years in visiting jails all over England and the Continent, and in endeavoring to render prison life less degrading and brutalizing. Wherever he went prison doors were unlocked as if he possessed a magic key; and by his life and books he did more to help prisoners than any other man.

It is only just over a hundred years since John Howard died; yet in his day persons could be put to death for stealing a horse or a sheep, for robbing dwellings, for defrauding creditors, for forgery, for wounding deer, for killing or maiming cattle, for stealing goods to the value of five shillings, or even for cutting a band in a hop plantation. And many persons who were innocent of any offense would lie in dungeons for years!

At his father’s death John Howard came into possession of a good property; and, marrying a lady some years older than himself, settled down on his estate and passed three years of quiet happiness.

Then a great grief came to him. His wife died, and Howard was bowed down with sorrow.

But the distress brought with it a longing to be a comfort to others; and he set out for Lisbon, which had just been visited by the great earthquake of 1755, with the hope of assisting the homeless and suffering.

France and England were then at war, and on his way thither he was captured by a French vessel and thrown into prison. He was placed in a dark, damp, filthy dungeon, and was half starved. For two months he was kept a prisoner, and as soon as he was free he set about obtaining the release of his fellow captives.

Some years later he became a sheriff of Bedford, and began visiting the prisoners in the gaol where John Bunyan wrote the Pilgrim’s Progress.

From the inquiries he made during the course of his visitations he was astonished to find that the jailers received no salary, and that they lived on what they could make out of the prisoners. As a result it often happened that those who had been acquitted at their trial were kept in prison long afterwards, because they were unable to pay the fees which the jailer demanded.

Horrified at the state in which he found the prison and at the abuses of justice that prevailed, John Howard determined to find out what was done in other parts of the kingdom, and visited a number of jails throughout the country. And fearful places he found them to be! Boys who were taken to jail for the first time were put with old and hardened criminals; the prisons were dirty and ill-smelling; the dungeons were dark and unhealthy; and, unless prisoners could afford to pay for comforts, they were obliged to sleep on cold bare floors, even delicate women not being exempted from such cruel treatment.

At Exeter he found two sailors in jail, having been fined one shilling each for some trifling offence, and owing £1 15s. 8d. for fees to the jailers and clerk of the peace. When he visited Cardiff he heard a man had just died in prison after having been there ten years for a debt of seven pounds. At Plymouth he found that three men had been shut up in a little dark room only five and a half feet high, so that they could neither breathe freely nor stand upright.

Hundreds of cases as bad or worse than these did he discover and bring before public notice.

He gave evidence before the House of Commons of what he had seen. Then Acts of Parliament were passed, providing that jailers should be paid out of the rates, that prisoners who were found not guilty should be set at liberty at once, that the prisons should be kept clean and healthy, and the prisoners properly clothed and attended to.

Determined that these Acts should not remain a dead letter, he went about the country seeing that what Parliament required was actually carried out.

Not contented with what he had already done, he traveled abroad, inspecting the prisons of France, Russia, Holland, Switzerland, Germany, and other countries, in order to see how they compared with those in Great Britain.

Strange to say, he discovered that in a number of cases they were in many ways better; and the prisoners, unlike their fellows in Britain, were generally employed in some useful manner.

When he was in London on one occasion he heard that there had been a revolt in the military prison in the Savoy. Two of the jailers had been killed, and the rioters held possession of the building. Howard set off for the prison, though he was warned that his life would not be safe if he ventured inside. Nothing daunted, he went amongst the prisoners, and soon persuaded them to go back to their cells peaceably, promising to bring their grievances before the authorities.

At Paris he was unable for a long time to get into that great prison house which then existed called the Bastille. Try as he would, he could gain no admittance. One day when he was passing he went to the gate of the prison, rang the bell and marched in. After passing the sentry he stopped and took a good look at the building, then he had to beat a hasty retreat, and narrowly escaped capture; but by that time he had partly accomplished his object.

When Howard was in Russia the empress sent a message saying she desired to see him; but he returned an answer that he was devoting his time to inspecting prisons, and had no leisure for visiting the palaces of rulers.

At Rome, however, he was prevailed on to go and see the Pope, on the express understanding that he should not be obliged to kiss his holiness’s toe; and he came away with a very pleasant remembrance of the Holy Father.

At Vienna the Emperor Joseph II specially requested an interview. Howard refused at first to meet the emperor’s wishes; but, on the English ambassador representing good might come of the visit, Howard went to see his majesty, and remained with him two hours in conversation, during which time he made the emperor acquainted with the bad state of some of the Austrian prisons. Once or twice the emperor was angered by Howard’s plainness of speech, but told the ambassador afterwards that he liked the prison reformer all the better for his honesty.

Having made up his mind to see the quarantine establishment at Marseilles, Howard made his way through France, though he was so feared and disliked by the Government that he was warned if he were caught in that country he would be thrown into the Bastille.

He disguised himself as a doctor, and after some narrow escapes arrived at Marseilles and visited the Lazaretto (or place of detention for the infected), though even Frenchmen were forbidden to do so. He took drawings of the place, and then went on a tour to many southern cities. He was at Smyrna while fever was raging with fury, and went amongst the sick and fever-stricken, fearless of the consequences.

In the course of his travels the ship in which he was a passenger was attacked by pirates, and John Howard showed himself as brave in actual battle as he was in fighting abuses; for he loaded the big gun with which the ship was armed nearly up to the muzzle with nails and spikes, and fired it into the pirate crew just in time to save himself and his companions from destruction. The books in which he gave an account of his experiences were eagerly read by the public, and produced a profound effect.

His last journey was to Russia. At Cherson he received an urgent request to visit a lady who had the fever. The place where she lived was many miles off, and no good horses were to be obtained. But he was determined not to disappoint her; so he procured a dray horse and started for his destination on a wintry night, with rain falling in torrents. As a result of this journey he was stricken down by the fever, and died 20th January, 1790.

Howard was a very hard worker, and a man of most frugal habits. He was often up by two o’clock in the morning writing and doing business till seven, when he breakfasted. He ate no flesh food, and drank no wine or spirits. He had a great dislike to any fuss being made about him personally; and, though £1500 was subscribed during his life to erect a memorial, it was, at his earnest desire, either returned to the subscribers or spent in assisting poor debtors.

But after his death a memorial was put up in St. Paul’s, and quite recently a monument has been erected at Bedford, where he first began his labors on behalf of the prisoners.

Eugenics such as this is how European civilization came about:

“yet in his day persons could be put to death for stealing a horse or a sheep, for robbing dwellings, for defrauding creditors, for forgery, for wounding deer, for killing or maiming cattle, for stealing goods to the value of five shillings, or even for cutting a band in a hop plantation.”

It wasn’t free, eggs had to be broken.