Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Cathedrals of Great Britain, by P. H. Ditchfield (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

The great Cathedral of St. Paul has abundant claims to the love and veneration of every Englishman. Situated in the heart of the city of London, it has ever been associated with the religious, social and civic life of the people; and as the great national Cathedral of England all the principal events in our country’s annals have been connected with St. Paul’s. Without doubt it is the finest and grandest building in London, if not in the world. Comparing it with St. Peter’s at Rome, we find that its dimensions are, of course, much smaller, though its grace and beauty are in no way inferior to the magnificent conception of Michael Angelo. It is the shrine of our national heroes, the chef d’œuvre of a great genius; its massive dome surmounted by a golden cross greets the traveller returning from beyond seas; its walls have echoed with the strains of high thanksgiving on the occasion of national victories and blessings, when kings and queens have come in solemn state to render thanks to Him who is the King of kings and Lord of lords. Just as Westminster was ever the church of the king and the government, so St. Paul’s was the church of the citizens.

The prominent place which St. Paul’s takes in the national and social life of England, in the great functions of Church and State, and in promoting the religious life of the people, is worthy of its best traditions, and at no time during its long history has it taken a higher place in the affections of the nation.

The Older Cathedrals of St. Paul’s

The present Cathedral, erected by the skill and genius of Sir Christopher Wren, is the third sacred edifice built upon this site. Indeed, Camden and certain early fanciful historians tell us of a Roman temple dedicated to Diana which they assert once stood here, erected during the time of the Diocletian persecution upon the site of an early Christian church. It is, however, certain that when Sir Christopher sank his foundations for the present building, he found beneath the interred bodies of mediæval times several Saxon stone coffins, and at a still lower depth Celtic and Roman remains, showing that the site had been set apart as a cemetery from very early times.

The earliest church of which we have sure records was erected in Saxon times by good King Ethelbert of Kent in the year 610. St. Mellitus, the companion of St. Augustine, was the first English Bishop of London, who came there in order to convert the East Saxons. Siebert, their king, joined with his uncle, Ethelbert, in building the Cathedral church, and the former probably founded the monastery of St. Peter called Westminster on Thorney Island, a place then “terrible from its desolate aspect—a mass of marsh and brushwood.”

But the Londoners loved their Paganism, and took not kindly to the new faith. The men of the “emporium of many nations” clung to their worship of Wodin and Thor, and not even the wise words of Mellitus in the new Cathedral could win them. It was the original design of Pope Gregory, who sent Augustine to our shores, to make the Cathedral of London the Metropolitan Church of England—a design which Augustine could not carry out on account of the violent opposition of the Pagan-loving people. Hence Canterbury was elevated to the position of the Metropolitan Church. Thirty-eight years passed away. At length the fiery spirit of the Londoners was subdued after three great missionary efforts, and they gradually learned the story of the cross. The Cathedral was beautified by Bishop Cedd, brother of St. Cedd or Chad of Lichfield, and Sebbe, King of Essex, and was fortunate in having St. Erkenwald as the fourth Bishop of London, who wrought great wonders and attracted many converts, restoring wealth and honour to his Cathedral. To his memory a golden shrine was erected which was much frequented by pilgrims. Saxon kings gave of their wealth to the endowment of the Cathedral, and many rich lands were granted to it, as the ancient charters bear witness.

Fire has always been a great foe to St. Paul’s. A very destructive conflagration raged in 961 A.D., and again in 1086 the Cathedral was wholly destroyed. We have no means of knowing what kind of architecture characterised this earliest fane, but probably it possessed round arches of stone, massive piers, and the usual characteristics of the Saxon style.

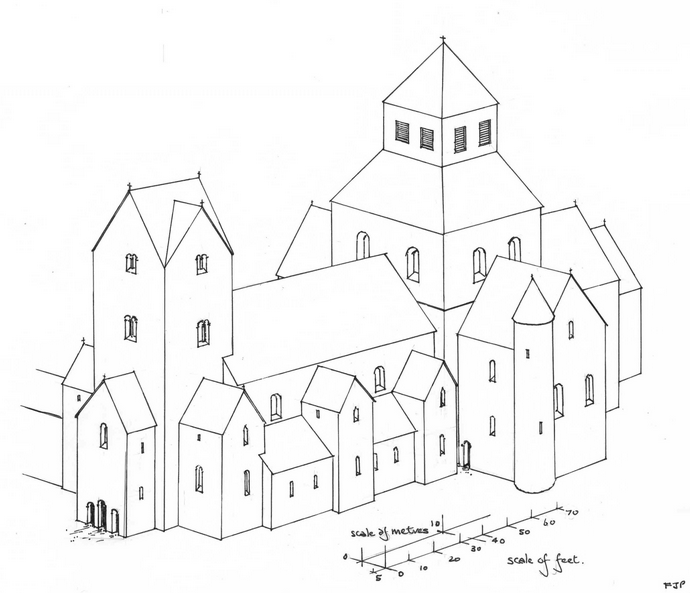

The energy of the English people is evident to all who study our national annals. When any alarming catastrophe occurs, immediately they arise to repair the disaster. As it was in the seventeenth century when the Great Fire swept over London and laid the city low, so it was in the eleventh. The Saxon church had no sooner been reduced to a heap of ruins than the Norman builders began to rear another noble pile. Bishop Maurice was the designer of this great edifice, which existed until the time of the Great Fire, though it was greatly injured by a fire in 1136.

A very noble church it must have been, with its walls ablaze with colour, richly-canopied tombs, pictures and frescoes, books, and vestments glittering with gold, silver and precious stones. It was the largest Cathedral in England.

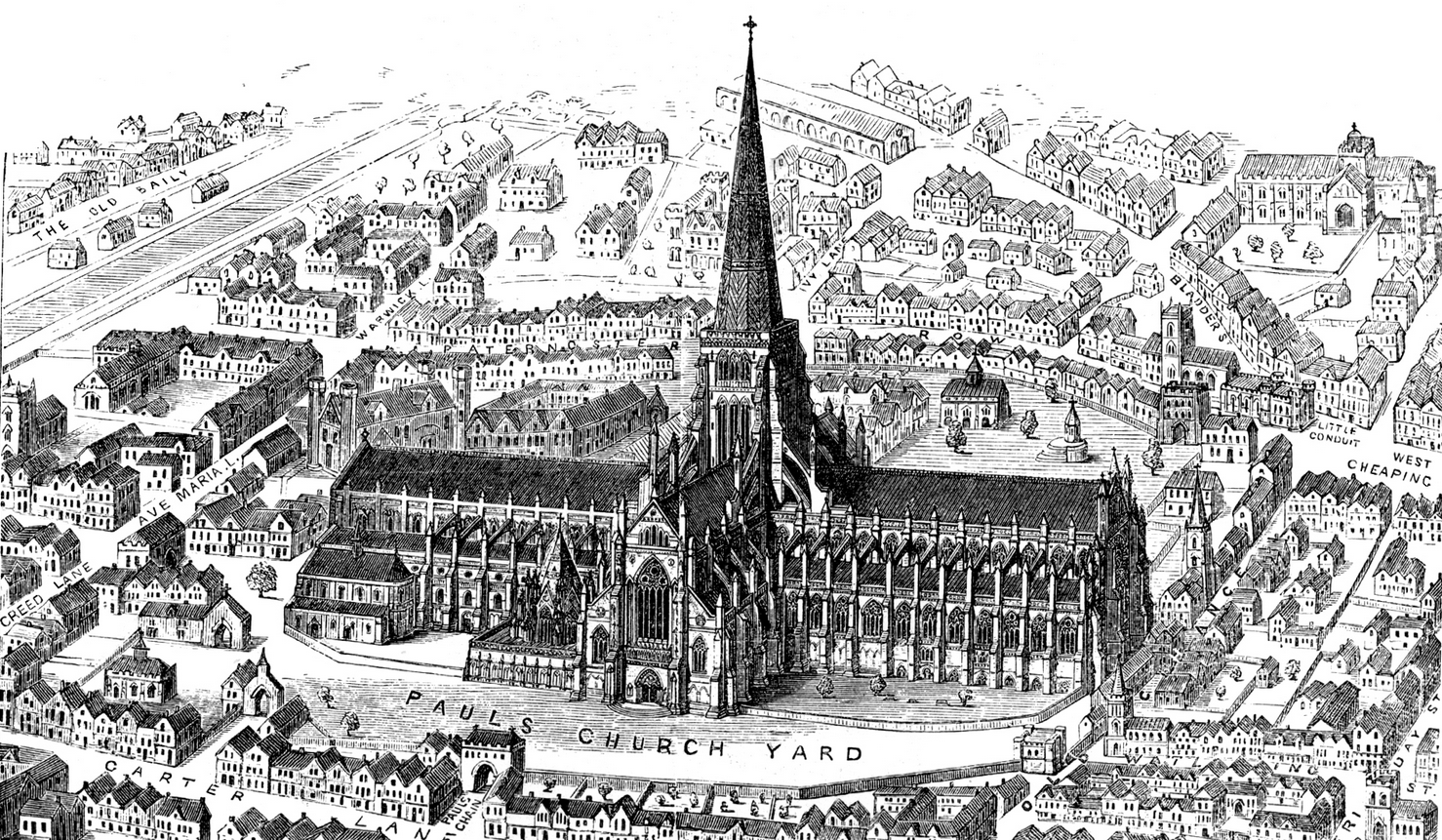

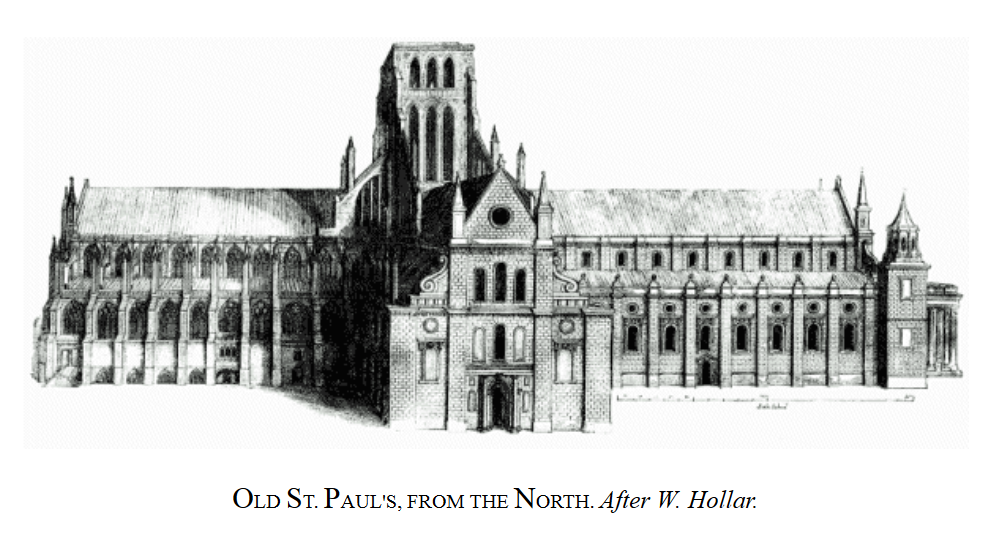

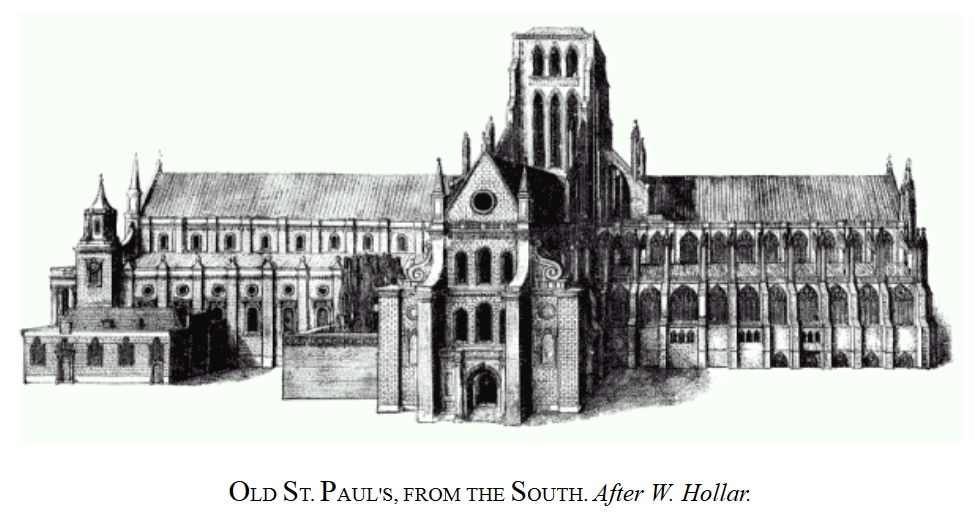

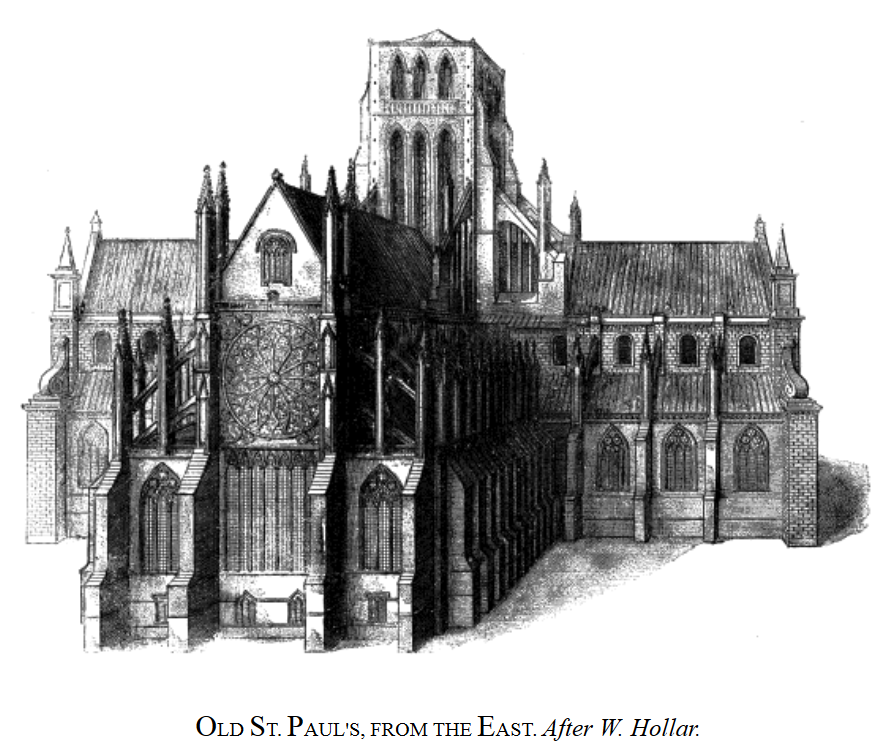

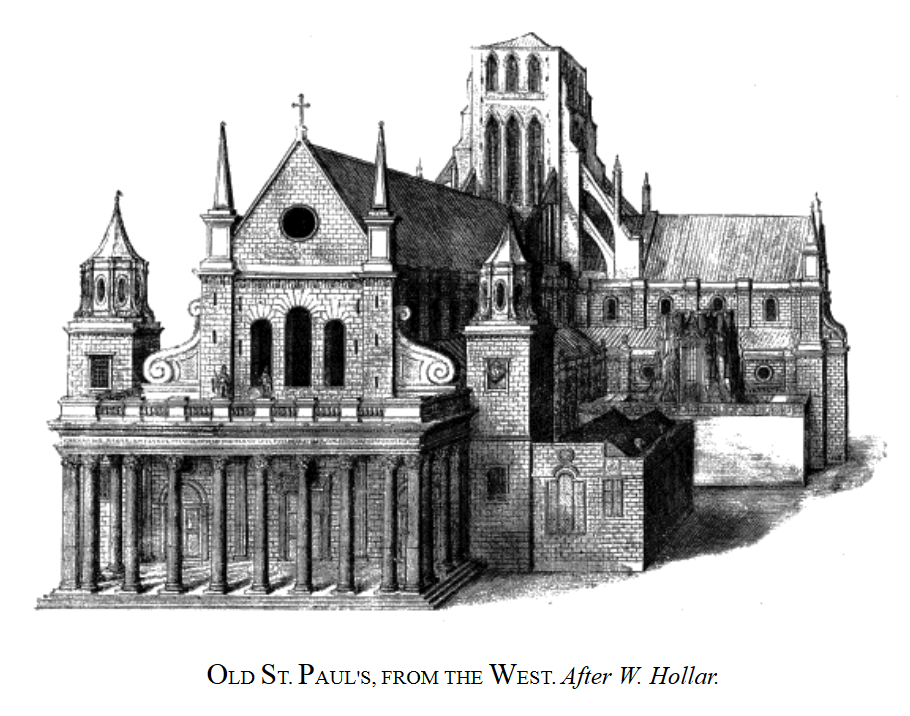

Old pictures tell us that it was cruciform, with a high tower and spire in the centre. The nave was long and noble, built in Norman style, having twelve bays. William of Malmesbury describes it as being “so stately and beautiful that it was worthily numbered amongst the most famous buildings.” At the west end were two towers for bells, and sometimes used as prisons. The central tower had flying buttresses. Besides the high altar there were seventy or eighty chantries, with their own altars all ablaze with rich draperies. St. Paul’s was also very rich in relics, among the number of which were two arms of St. Mellitus, a knife of our Lord, some hair of Mary Magdalene, blood of St. Paul, milk of the Virgin, the hand of St. John, the skull of Thomas à Becket, the head of King Ethelbert. But “the pride, glory and fountain of wealth” to St. Paul’s was the body of St. Erkenwald, covered with a golden shrine, behind the high altar. Dean Milman states that in the year 1344 the offerings made by pilgrims alone amounted to £9000. The choir was rebuilt in 1221, and the Lady Chapel added in 1225. There was a very large east window, and a rose window over it. Buttresses crowned with pinnacles and adorned with niches supported the walls. The interior view, judging from Hollar’s engraving, must have been very fine. The pillars and arches were Late Norman. The choir consisted of twelve bays and was finished about the end of the thirteenth century. We have few records to tell us about the details of the building of this old St. Paul’s. In 1312 the nave was paved with marble, and two years later a spire of wood was raised to the height of 460 feet, then the highest in the world. This was damaged and ultimately destroyed by lightning.

The Precincts

We will now examine the precincts of the Cathedral. A wall surrounded the vast space which extended from Carter Lane on the south to Creed Lane and included Paternoster Row. This wall had six gates, the site of two of which is marked by St. Paul’s Alley and Paul’s Chain. The Bishop’s Palace occupied the north-west corner of this space, and on the north were some cloisters decorated with mural paintings representing the Dance of Death, a favourite subject of mediæval painters, of which Holbein’s conceptions are best known. This cloister was on the site of Pardon Churchyard, where a chapel was founded by Gilbert à Becket, the father of St. Thomas of noted memory. The chapter-house stood on the south side of the Cathedral, and was a very beautiful structure, so beautiful that Protector Somerset coveted the materials for his palace in the Strand, and took down and removed them.

At the north-east corner of the precincts stood the famous Paul’s Cross, the scene of so many famous preachings and strange events, where folk-motes were held, Papal bulls promulgated, Royal proclamations made, excommunications and public penances declared, and sometimes riots and tumults excited. Paul’s Cross played a very prominent part in the history of old London. Near the Pardon Churchyard once stood the Parish Church of St. Faith, called the Chapel of Jesus; but this was destroyed, and the parishioners received in lieu of it a church in the crypt of the Cathedral. Fuller, remarking on this and on the existence of the Parish Church of St. Gregory on the Thames side of the Cathedral, quaintly observed, “St. Paul’s may be called the Mother Church indeed, having one babe in her body and another in her arms.”

St. Paul’s was the centre of the life of London. Its great bell summoned the London citizens to their three annual folk-motes at Paul’s Cross, where all the municipal business of the city was transacted, disputes settled, grievances stated and rights vindicated. Very turbulent and jealous of their liberties were these good citizens, and even the sovereign will of kings and queens must bow before the noisy clamours of the burghers of London. The bell of St. Paul’s, like that of its famous brother “Roland” at Ghent, seemed endowed with a human voice when it summoned the multitudes to their meeting-place at the Cross, and declared in loud tones the will of the people.

Historical Events

The citizens might well love to have their church in their midst, for the ecclesiastical power was very strong, and often enabled them to defy the will of tyrannical kings or troublesome barons. In the time of the Conqueror, Bishop William of London obtained from the king a renewal of their privileges of which the monarch had deprived them. In gratitude for this benefit, the mayor, aldermen and livery companies of London used to visit the tomb of the good bishop in grand procession, in order to pray for his soul, and to commemorate his great services.

In the reign of Stephen civil war raged, and the country was divided into hostile camps, one siding with the king and the other with the Empress Maud. The citizens of London were not doubtful in their opinions. They rang the great bell of St. Paul’s, summoned their folk-mote, and loudly declared that it was the privilege of the citizens of their great city to elect a sovereign for England, and with one voice supported Stephen.

Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, was a favourite of the citizens, though hated by his sovereign. Gilbert à Becket, his father, had a shop in Cheapside on the site of Mercers’ Hall, whither the fair Saracen is said to have followed him from the Holy Land, where he had gone on a Crusade. He built a chapel in the churchyard of St. Paul, and his son, the famous archbishop, was well known to the citizens. Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, however, had taken the side of the king, Henry II, in the fatal quarrel, and aroused the anger of the prelate. A curious scene took place in consequence in old St. Paul’s. A priest was celebrating mass, when a man approached, thrust a paper into his hand, and cried aloud, “Know all men that Gilbert, Bishop of London, is excommunicated by Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury.” The news spread fast among the citizens. Foliot at first attempted to defy the dread sentence; but he knew something of the nature of the citizens of London, and wisely bowed before the decree, which the people were quite willing to enforce.

St. Paul’s was the scene of a memorable council in the reign of Richard Cœur de Lion, who was crusading in Palestine. The bishops, together with the king’s brother John, met in the nave and condemned Longchamp to resign the office of justiciary, and to surrender the castles which he held in the name of the king. During this reign a factious demagogue, William Fitz-Osbert, equally distinguished by the length of his beard and the vehemence of his eloquence, called the people together at Paul’s Cross, and excited them to rebel against their oppressors. Bishop Hubert, however, calmed the multitude on the eve of a formidable rising. The people deserted their leader, who took refuge in St. Mary-le-Bow Church, which was set on fire, and Fitz-Osbert suffered death at the hands of the hangman. Thus from the tyranny of a Royal favourite, and from that of a mob orator, the people were saved by the influence of the Church in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

A still greater service did St. Paul’s render to England. Here was assembled a grand concourse of bishops, abbots, deans, priors and barons, to withstand the oppressive lawlessness of King John. Here Magna Charta was first devised. Here, at the instigation of Archbishop Langton, the barons and chief men swore to maintain the principles of the Charta, and to protect the liberties of Englishmen.

St. Paul’s also set itself in opposition to the authority of the Pope; and when a Papal legate sought to enthrone himself in St. Paul’s, he was openly resisted by Cantelupe, Bishop of Worcester. Boniface of Savoy, “the handsome Archbishop,” brought with him fashions strange enough to English folk. His armed retainers pillaged the markets, and he felled to the ground, with his own fist, the prior of St. Bartholomew, Smithfield, who presumed to oppose his visitation. He came to St. Paul’s to demand first-fruits from the Bishop of London, but deemed it advisable to wear armour beneath his robes. He found the gates of the Cathedral closed against him; but he fared better than two canons of the Papal party, who were killed by the citizens a few years later when they attempted to enter St. Paul’s. London was aroused by these Italian priests, and the citizens at length besieged Lambeth Palace and drove the obnoxious archbishop beyond seas.

Again and again the tocsin sounded, as St. Paul’s bell rang clear and loud, and the citizens seized their weapons and formed their battalions beneath the shadow of the great church. Now it was to help Simon de Montfort against the king; now to seize the person of the obnoxious Queen Eleanor, who was trying to escape by water from the Tower to Windsor, and who was rescued from their hands by the Bishop of London, and found refuge in his palace. Now the favourites of Edward II excited their rage, especially the Bishop of Exeter, the king’s regent, who dared to ask the Lord Mayor for the keys of the city, and paid for his temerity with his life.

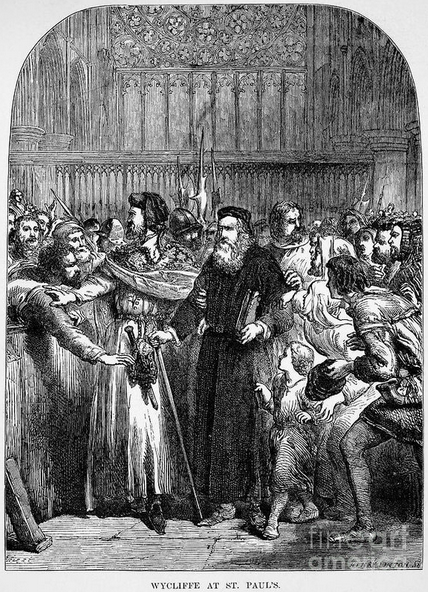

An incident which shows the attachment of the people to their church and bishop occurred in the reign of the third Edward. Wycliffe was summoned by Bishop Courtenay to appear before a great council at St. Paul’s. But the reformer did not come alone; to the surprise of his accusers he arrived attended by a large following of friends, among whom were John of Gaunt and Lord Percy. These powerful supporters of Wycliffe attacked the bishop with angry words.

News was flashed among the citizens that John of Gaunt had threatened their bishop and vowed to drag him out of the church by the hair. They gathered together in angry crowds, and would have slain the duke and sacked his palace, the Savoy, in the Strand, if the bishop had not interfered on behalf of his enemy. Wycliffe and Lollardism did not then find much favour with the people of London.

There were reformers within the Church who were quite as eager to correct abuses as those outside the fold. Among these was Bishop Braybroke of London, who lived in the time of Edward IV. He contended for the sanctity of the sacred building, inveighed against the practice of using it as an exchange, of playing at ball within the precincts or within the church, and of shooting the pigeons which then as now found sanctuary at St. Paul’s.

The chronicles of the Cathedral tell the story of the troublous times of the Wars of the Roses. We see Henry IV pretending bitter sorrow for the death of the murdered Richard, and covering with cloths of gold the body, which had been exhibited to the people in St. Paul’s. We see Henry V returning in triumph from the French wars, riding in state to the Cathedral, attended by “the mayor and brethren of the city companies, wearing red gowns with hoods of red and white, well-mounted and gorgeously horsed, with rich collars and great chains, rejoicing at his victorious returne.” Then came Henry VI, attended by the bishops, the dean and canons, to make his offering at the altar. Here the false Duke of York took his oath on the Blessed Sacrament to be loyal to the king. Here the rival houses swore to lay aside their differences, and to live at peace. But a few years later saw the new king, Edward IV, at St. Paul’s, attended by great Warwick, the king-maker, with his bodyguard of 800 men-at-arms. Strange were the changes of fortune in those days. Soon St. Paul’s saw the exhibition of the dead body of the king-maker, and not long afterwards that of the poor dethroned Henry, and Richard came in state here amid the shouts of the populace. After the defeat of the conspiracy of Lambert Simnel, Henry VII celebrated a joyous thanksgiving in the Cathedral, and here, amid much rejoicing, the youthful marriage of Prince Arthur with Catherine of Arragon took place, when the conduits at Cheapside and on the west of the Cathedral ran with wine, and the bells rang joyfully, and all wished happiness to the Royal children whose wedded life was destined to be so brief.

The Reformation and After

At the dawn of the Reformation period we will pause in order to try and realise what kind of scenes took place daily in the great Cathedral, and what vast numbers were employed on the staff. The members of the Cathedral body in the year 1450 included the following:—The Bishop, the Dean, the four Archdeacons, the Treasurer, the Precentor, the Chancellor, thirty greater Canons, twelve lesser Canons, about fifty Chaplains or Chantry-Priests and thirty Vicars. Of inferior rank to these were the Sacrist, the three Vergers, the Succentor, the Master of the Singing School, the Master of the Grammar School, the Almoner and his four Vergers, the Servitors, the Surveyor, the twelve Scribes, the Book Transcriber, the Bookbinder, the Chamberlain, the Rent-collector, the Baker, the Brewer, the Singing-men and Choir Boys, of whom priests were made, the Bedesmen and the poor folk. In addition to these must be added the servants of all these officers—the brewer, who brewed in the year 1286, 67,814 gallons, must have employed a good many; the baker, who ovened every year 40,000 loaves, or every day a 100, large and small; the sextons, grave-diggers, gardeners, bell-ringers, makers and menders of the ecclesiastical robes, cleaners and sweepers, carpenters, masons, painters, carvers and gilders. One can very well understand that the Church of St. Paul alone found a livelihood for thousands.

The inventory of church goods belonging to the Cathedral in 1245 exists, and is worth studying. It enumerates sixteen chalices, five of gold and the rest of silver-gilt. A chalice of Greek work had lost its paten, but retained its reed (calamus), a relic of the time when the deacon carried the chalice to the people, and each one drank of its hallowed contents through a long narrow pipe, which was usually fastened on a pivot to the bottom of the cup of the chalice. Amongst other curiosities of the inventory are three poma, or hollow balls of silver, so contrived as to hold hot water or charcoal embers for the warming of the hands of the celebrant during mass.

Of shrines and relics we have already spoken. There were three episcopal staves, and also a precentor staff of ivory with silver-gilt and jewelled enrichments, and a baculus stultorum for use at the profane travesty called the feast of fools. Among the mitres were two for the boy-bishop’s use on St. Nicholas Day. There were thirty-seven magnificent copes, and forty-four others, and thirty-four specially fine chasubles.

The inventory of 1402 supplies some curious information as to the manner in which the numerous and costly vestments were arranged when not in use. In the treasury, on the west, stood a wardrobe, armariolum, in which were twenty-four perticæ, pegs, or rods, or frames, from which the copes and chasubles could be suspended, one pertica holding from three to six copes. The vestments were arranged according to colour. Three other wardrobes were also stored with goodly vestments, and there were twenty-six in daily use. The total is 179 copes, fifty-one chasubles and ninety-two tunicles, and the colours were red, purple, black, white, green, yellow, blue, red mixed with blue.

We have remarked that St. Paul’s was the centre of the social life of the people in olden days, which led to some abuses.

Francis Osborn says, “It was the fashion in those days, and did so continue until these, for the principal gentry, lords and courtiers, and men of all professions, to meet in St. Paul’s by eleven of the clock, and walk in the middle aisle till twelve, and after dinner from three to six, during which time they discoursed of business, others of news.”

Shakespeare represents Falstaff in Henry V as having “bought Bardolph in Paul’s”; and Dekker thus speaks of the desecration of the sanctuary, “At one time in one and the same rank, yea, foot by foot, elbow by elbow, shall you see walking the knight, the gull, the gallant, the upstart, the gentleman, the clown, the captain, the apple-squire, the lawyer, the usurer, the citizen, the bankrout, the scholar, the beggar, the doctor, the idiot, the ruffian, the cheat, the Puritan, the cut-throat, highman, lowman and thief; of all trades and professions some; of all countries some. Thus while Devotion kneels at her prayers, doth Profanation walk under her nose in contempt of Religion.”

Here lawyers received their clients; here men sought service; here usurers met their victims, and the tombs and font were mightily convenient for counters for the exchanges of money and the transaction of bargains, and the rattle of gold and silver was constantly heard amidst the loud talking of the crowd.

Gallants enter the Cathedral wearing spurs, having just left their steeds at “The Bell and Savage,” and are immediately besieged by the choristers, who have the right of demanding spur-money from anyone entering the building wearing spurs.

Nor are the fair sex absent, and Paul’s Walk was used as a convenient place for assignations. Old plays are full of references to this practice.

Later on the nave was nothing but a public thoroughfare, where men tramped carrying baskets of bread and fish, flesh and fruit, vessels of ale, sacks of coal, and even dead mules and horses and other beasts. Hucksters and pedlars sold their wares.

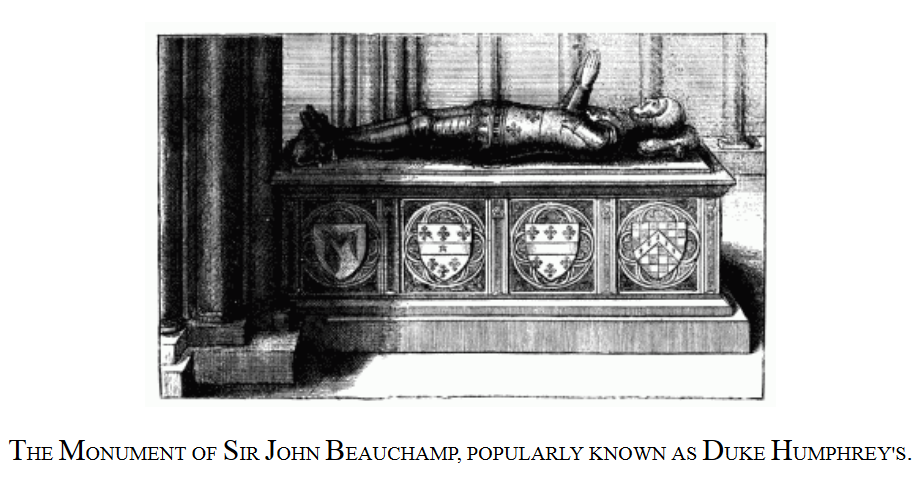

Duke Humphrey’s tomb was the great meeting-place of all beggars and low rascals, and they euphemistically called their gathering “a dining with Duke Humphrey.”

Much more could be written of this assembly of all sorts and conditions of men, but we have said enough to show that the Cathedral had suffered greatly from desecration and abuse. Indeed, an old writer in 1561 declared that the burning of the steeple in that year was a judgment for the scenes of profanation which were daily witnessed in old St. Paul’s. He writes, “No place has been more abused than Paul’s has been, nor more against the receiving of Christ’s Gospel; wherefore it is more marvel that God spared it so long, rather than He overthrew it now. From the top of the spire at coronations, or at other solemn triumphs, some for vain glory used to throw themselves down by a rope, and so killed themselves vainly to please other men’s eyes,” and much more to the same effect.

But the strictness of the worthy divine did not altogether cure the evils against which he railed. Eight years later the first great lottery was drawn before the west doors. There were 10,000 lots at ten shillings each, and day and night from January 11 to May 6 the drawing went on. The prizes were pieces of plate, and the profits were devoted to the repair of the havens of England. So profitable was the lottery that another took place here in 1586, the prizes being some valuable armour.

At the dawn of the Reformation we see Henry VIII in all the pomp and glory of mediæval pageantry riding in state to the Cathedral to be adorned with a cap of maintenance and a sword presented to him by the Pope. There was no sign yet of any breach of alliance between the Roman Pontiff and him whom he honoured with the title of “Defender of the Faith.” Lollardism in spite of some burnings spread, and the western tower of the Cathedral earned the name of the Lollards’ Tower, as several were imprisoned there.

Wolsey, the great cardinal, in the height of his prosperity often came to St. Paul’s, and very gorgeous were the scenes which took place there, when thanksgiving for the peace between England, France and Spain was celebrated, when Princess Mary was betrothed to the Dauphin of France, and Charles V. proclaimed emperor. But signs of trouble were evident. Bishop Fisher thundered forth invectives against the works of Luther, which were publicly burnt in St. Paul’s Churchyard. A few years later there was a burning in the Cathedral of heretical books in the presence of the cardinal, who caused some of Luther’s followers to march round the blaze, throw in faggots, and thus to contemplate what a burning of heretics would be like, and be thankful that only their books and not their bodies were condemned to the flames.

During this troubled time and in Mary’s reign, St. Paul’s was often used as a place of trial for heretics, but Paul’s Cross was a fruitful breeding place for the principles of the Reformation. Here Latimer, Ridley, Coverdale, Lever, and a host of others used to inveigh against the errors of Rome and deny the authority of the Pope. Here they exhibited the Boxley Rood, with all the tricks whereby it was made to open its eyes and lips, and seem to speak. The crowd looked on, and roared with laughter, seized the miraculous Rood, and broke it in pieces. And then a strange thing happened in the Cathedral. One night all the images, crucifixes and emblems of Popery were pulled down. Terrible havoc was wrought, chalices and chasubles, altars and rich hangings, books and costly vestments, were all seized and sold, and helped to increase that vast heap of spoil which the greedy ministers of Edward VI. gathered from the wasting of the Church’s goods. Tombs were pulled down, chantries and chapels devastated, cloisters and chapter-houses removed bodily to Somerset House by Protector Somerset for the building of his new palace, and all was wreckage, spoliation and robbery.

Then came the fitful restoration of the “old religion,” and many riots ensued, many ears were nailed to the pillory nigh Paul’s Cross; many Protestants condemned in the Cathedral to the fires at Smithfield, and many horrors enacted which Englishmen like not to remember.

With the coming of Elizabeth more peaceful times ensued, but the Cathedral was in a sorry condition. Desecration reigned within. Then in 1561 the spire caught fire, blazed and fell, destroying parts of the roof. The clergy and citizens soon set to work to repair the damage, but the glory of “old St. Paul’s” had departed, and its ruinous condition was the distress of rulers and the despair of the citizens and clergy.

Elizabeth often visited the Cathedral, and troubled Dean Nowell by her plainly-spoken criticisms. Felton was hung at the bishop’s gates for nailing a Papal bull to the palace doors, which declared the queen to be a heretic and released her subjects from their allegiance. This attempt of the Pope to dethrone the Virgin Queen was not very successful. Some other conspirators suffered for their crimes in the following reign in the precincts, four of the gunpowder conspirators being hung, drawn and quartered before the west doors. Here also Garnet, the Jesuit, shared a like fate.

King James attempted to restore the Cathedral, but his efforts came to nothing. Charles I. did something, and from the designs of Inigo Jones built a portico at the west end, and made some other improvements, but the troubles of the Civil War intervened, and the money which had been collected by Archbishop Laud and the generosity of the citizens of London was seized by the Parliament and converted to other and baser uses.

The Civil Wars

Desolation reigned supreme in the once glorious church when Puritan rage had vented itself on its once hallowed shrines and sacred things. Cromwell’s troopers “did after their kind.” Whatever beautiful relics of ancient worship reforming zeal had left were doomed to speedy destruction. In the western portico built in the last reign shops were set up for sempstresses and hucksters; Dr. Burgess, a Puritan divine, thundered forth in his conventicle set up in the east of the building; and the rest of the Cathedral was turned into a cavalry barracks.

The conduct of the rough soldiers created great scandal. They played games, brawled and drank in the church, prevented people from going through the nave, and caused such grievous complaints, that an order was passed forbidding them to play at ninepins from six o’clock in the morning to nine in the evening.

The Mercurius Eleneticus of 1648 waxes scornful over the misdeeds of these rough riders, and scoffs sarcastically: “The saints in Paul’s were last week teaching their horses to ride up the great steps that lead to the Quire, where (as they derided) they might perhaps learn to chant an anthem; but one of them fell and broke his leg, and the neck of his rider, which hath spoilt his chanting, for he was buried on Saturday night last, a just judgment of God on such a profane and sacrilegious wretch.”

The famous Cross in the churchyard, which according to Dugdale, “had been for many ages the most noted and solemn place in this nation for the greatest divines and greatest scholars to preach at, was, with the rest of the crosses about London and Westminster, by further order of the Parliament, pulled down to the ground.”

After the Great Fire

With the restoration of the monarchy came the restoration of the Cathedral. Dr. Wren, the great architect, was consulted, plans were discussed, Wren prepared himself for the great work, and all was in readiness, when the Great Fire broke out, and completed the ruin which had already begun. It, however, paved the way for the erection of the grand church which will ever be associated with the genius of its great architect.

Both the diarists, Pepys and Evelyn, speak of the melancholy spectacle of the great ruin. Pepys laments over the “miserable sight of Paul’s church, with all the roof falling, and the body of the nave fallen into St. Faith.”

And Dryden sings:—

“The daring flames press’d in and saw from far The awful beauties of the sacred quire: But since it was profaned by civil war Heaven thought it fit to have it purged by fire.”

Evelyn, in his diary, describes his visit to the church before the fire with Dr. Wren, the bishop, dean and several expert workmen. “We went about to survey the general decay of that ancient and venerable church, and to set down in writing the particulars of what was fit to be done. Finding the main building to recede outwards, it was the opinion of Mr. Chickley and Mr. Prat that it had been so built ab origine for an effect in perspective, in regard of the height; but I was, with Dr. Wren, quite of another judgment, and so we entered it: we plumbed the uprights in several places. When we came to the steeple, it was deliberated whether it were not well enough to repair it only on its old foundation, with reservation to the four pillars; … we persisted that it required a new foundation not only in regard of the necessity, but that the shape of what stood was very mean, and we had a mind to build it with a noble cupola, a form of church-building not as yet known in England, but of wonderful grace….”

Then came the Great Fire, so graphically described by Evelyn. He writes: “The stones of Paul’s flew like granados, the melting lead running down the streets in a stream, and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness, so as no horse or man was able to tread on them, and the demolition had stopped all the passages, so that no help could be applied.”

This Great Fire roused again the energy and indomitable spirit of Englishmen. They beheld without alarm the ashes of their houses, and the destruction of their great city. They felt that the eyes of Europe were upon them. A new city was to be built worthy of their nation, worthy of the great centre of the commerce of the world. But to restore St. Paul’s was a stupendous work. Some were for rebuilding on the old walls. Pepys describes the ruins: “I stopped at St. Paul’s, and then did go into St. Faith’s Chapel, and also into the body of the west part of the church; and do see a hideous sight of the walls of the church ready to fall, that I was in fear as long as I was in it; and here I saw the great vaults underneath the body of the church.” And again: “Up betimes, and walked to the Temple, and stopped, viewing the Exchange, and Paul’s, and St. Faith’s, where strange how the very sight of the stones falling from the top of the steeple do make me sea-sick.”

They began to repair the west end for service against the advice of Wren, and Dean Sancroft was obliged to confess to the architect,—

“What you whispered in my ear at your last coming here is come to pass. Our work at the west end of St. Paul’s is fallen about our ears.”

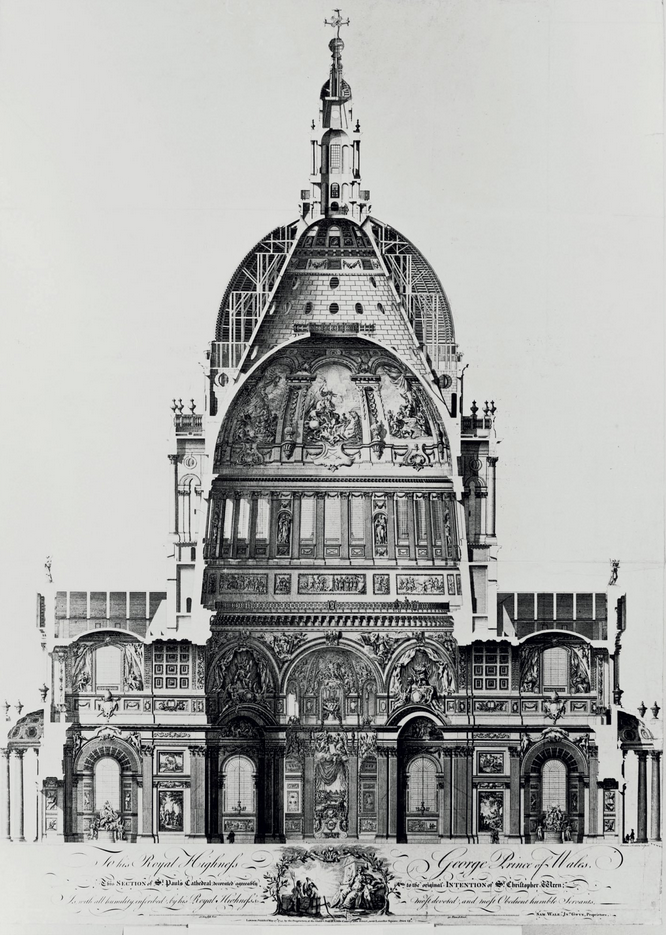

At last the order was given to take down the walls, clear the ground, and proceed according to the plans of Wren. He was thwarted and distressed by the interference of many. His original design was to build it in the form of a Greek cross, but to this the clergy objected, and a Latin cross was decided upon.

In 1674 the workmen began to clear away the old ruins, no light task, but in the end it was accomplished, the first stone of the new Cathedral being laid on June 21, 1675. In October 1694 the choir was finished, and on December 2, 1697, Divine service was performed for the first time in the new edifice. It was a special thanksgiving for the Peace of Ryswick, a peace which settled our Dutch William more securely on the throne of England. His Majesty wished to attend the service, but it was feared that amongst the vast crowds there might be too many Jacobites, and he was persuaded to remain at his palace. Bishop Compton preached a great sermon on the occasion from the text, “I was glad when they said unto me, we will go into the House of the Lord.”

Thirteen years elapsed before the highest stone of the lantern on the cupola was laid by Wren’s son, and the magnificent building was completed by the skill, genius and determination of one man, whose memory deserves to be ever honoured by all Englishmen.

The men of his own day did not treat him worthily. During the building of the Cathedral he was beset by all the annoyances jealousy and spite could suggest, and at the end of his long and useful career, by the intrigues of certain German adventurers, he was deprived of his post of Surveyor-General after the death of Queen Anne. He retired to the country, and spent the few remaining years of his life in peaceful seclusion, occasionally giving himself the treat of a journey to London, in order that he might feast his eyes on that great and beautiful church which his skill had raised.

His was the first grave sunk in the Cathedral, and it bears the well-known inscription, than which none could be more fitting:—

LECTOR, SI MONUMENTUM REQUIRIS CIRCUMSPICE.

The Existing Cathedral—Exterior

The new St. Paul’s is without doubt the grandest building in London. Perhaps the finest view is obtained from the approach by Ludgate Hill, and the grandeur of its majestic dome is most impressive. The style is English Renaissance. We will begin our survey with the West Front, which was erected last, and therefore bears the stamp of Wren’s matured genius. There are two storeys. In the lower there is a row of Corinthian columns arranged in pairs, and in the second storey a similar series. On the triangular pediment above is a carving of the Conversion of St. Paul, while a statue of the saint crowns the apex, the other statues representing SS. Peter and James and the four Evangelists. Two towers stand, one on each side of the front, and complete a superb effect. These contain a grand peal of twelve bells, one of which, called Great Paul, fashioned twenty years ago, is one of the largest in the world. Rich marbles, brought from Italy and Greece, adorn the pavement.

Proceeding to the north side we note the two-storied construction, the graceful Corinthian pilasters, arranged in pairs, with round-headed windows between them; the entablature; and then, in the second storey, another row of beautiful pilasters of the Composite order. Between these are niches where one would have expected windows; but this storey is simply a screen to hide the flying buttresses supporting the clerestory, as Wren thought them a disfigurement. The walls are finished with a cornice, which Wren was compelled by hostile critics to add, much against his own judgment. There are some excellently-carved festoons of foliage and birds and cherubs, which are well worthy of close observation. The North and South Fronts have Corinthian pillars, which support a semi-circular entablature. Figures of the Apostles adorn the triangular-shaped head and balustrade. The Royal arms appear on the north side, and a Phœnix is the suitable ornament on the south, signifying the resurrection of the building from its ashes.

The south side is almost exactly similar to the north. The east end has an apse.

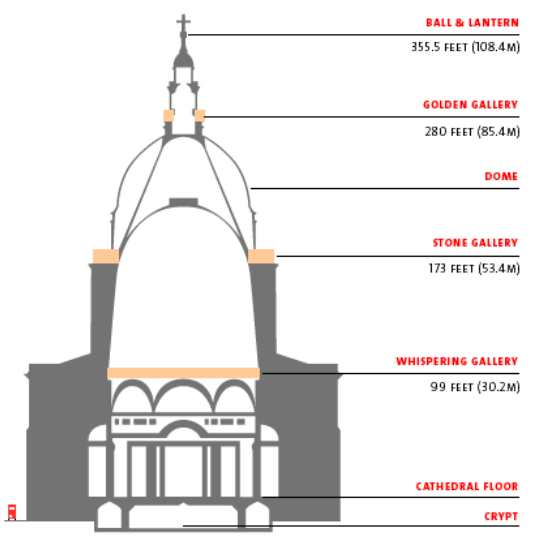

The magnificent Dome is composed of an outward and inward shell, and between these there rises a cone-shaped structure which supports the lantern, crowned with its golden ball and cross. The arrangement of this is most complex, and is a witness to the marvellous skill of the architect. Above the row of Composite columns is a gallery, which affords a good view to those who are anxious to climb. Above the actual dome is the Golden Gallery, and then the lantern, roofed with a dome bearing the ball and cross. The whole height is 365 feet.

Interior of the Building

The view on entering the Cathedral at the west is most impressive. The magnitude of the design, the sense of strength and stability, as well as the beauty of the majestic proportions, are very striking. Over the doors we see carvings of St. Paul at Berea. A gallery is over the central doorway, and here is a good modern window.

The nave has a large western bay with chapels, three other bays, and a large space beneath the west wall of the dome. It has three storeys, the lofty arches, a storey which in a Gothic church would be termed the triforium, and a clerestory. Grand Corinthian pilasters are attached to the massive piers, with wonderfully-wrought capitals, which support the entablature. The arches spring from smaller pilasters joined to the larger ones. Great arches springing from the triforium piers span the nave, and between these arches are dome-shaped roofs. High up there are festoons of carving. The aisles have three large windows, and Composite pilasters adorn the walls and support the vault. The north chapel at the west end is the Morning Chapel, and is adorned with mosaics and modern glass, in memory of Dean Mansell (1871). The south chapel is called the Consistory, and once held Wellington’s monument, to which the marble sculptures refer. Here is an unusual Font of Carrara marble.

The Dome is supported by immense and massive masonry. Above the arches a cornice runs round, supporting the Whispering Gallery. Then the dome begins to curve inward. Above is a row of windows, set in groups of three, separated by niches recently filled with statues of the Fathers, and then the dome is completed and painted by Sir James Thornhill with scenes from the life of St. Paul. These are too faint and too far distant to be easily observed. The painter nearly lost his life through stepping backward in order to see the effect of his brush, and nearly fell from the scaffold. His companion just saved his life by flinging a brush at the painting, and Thornhill rushed forward to rescue his work, and thus his life was saved.

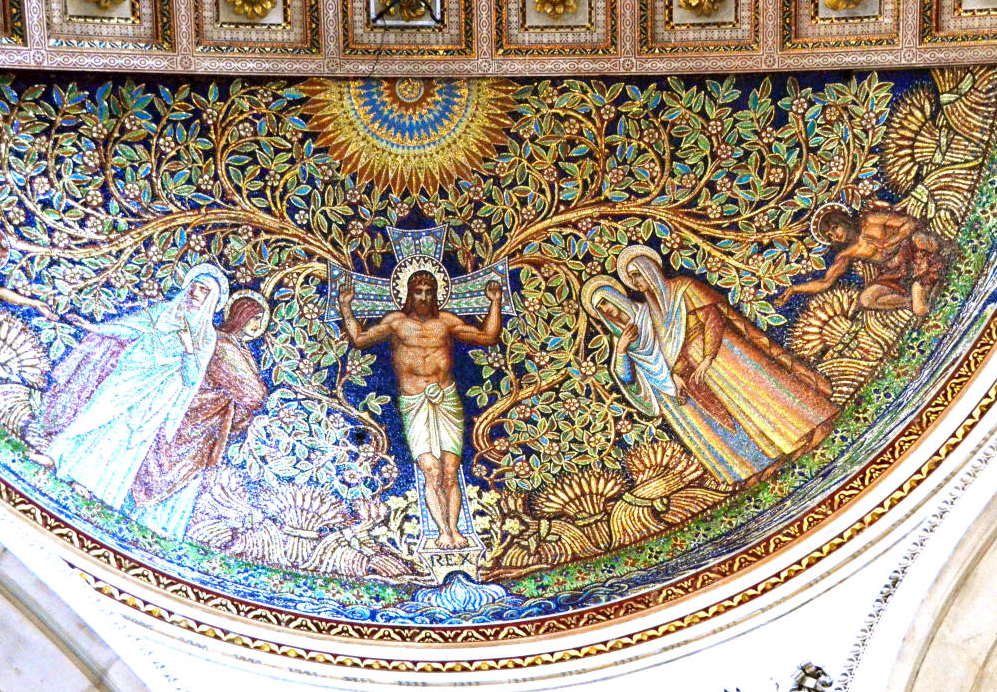

The Pulpit is made of rich marble, and the lectern was made in 1720. The modern mosaics are of unique interest, and add much to the beauty of the Cathedral. To Sir William Richmond the credit of this work is mainly due, and for some of earlier portions to Mr. G.F. Watts, R.A.

The Transepts have good windows, representing (north) the twelve founders of English Christianity, and south, the first twelve Christian Saxon kings, and also a window in memory of the recovery from illness of His Majesty Edward VII when Prince of Wales.

The Choir has some wonderfully-carved stalls by the famous Grinling Gibbons, and these bear the names of the prebendaries attached to the Cathedral, with the parts of the Psalter which each one had to say each day, an arrangement similar to that at Lincoln.

The Reredos is a noble example of modern work, and is worthy of close examination. Behind it is the Jesus Chapel, containing a monument of Canon Liddon. The mosaic decorations of the choir are the work of Sir William Richmond, and are worthy of the highest praise.

Monuments

One feature of St. Paul’s especially endears it to us, and that is that there lie all that is mortal of many of our national heroes. Westminster is richer in its many monuments of great poets and writers; but the makers of the Empire and most of our distinguished painters are entombed in the “citizens’ church.” We can only point out the tombs of the most illustrious.

- Nave (North Aisle)—

- Wellington (d. 1852), the hero of Waterloo.

- Gordon (d. 1890), slain at Khartoum.

- Stewart, General (d. 1880), who tried to rescue Gordon.

- Melbourne, Viscount (1848), Queen Victoria’s first Prime Minister.

- North Transept—

- Sir Joshua Reynolds (1792), by Flaxman.

- Rodney, Admiral (1790), the hero of Martinique.

- Picton (1815), slain at Waterloo.

- Napier, General (1860), author of Peninsular War.

- Ponsonby, General (1815), killed at Waterloo.

- Hallam, the historian (1859).

- Johnson, Samuel (1784).

- South Transept—

- Nelson, Admiral.

- Sir John Moore (1806), killed at Corunna.

- Turner, Joseph, R.A. (1851), painter.

- Collingwood, Admiral (1810), Colleague of Nelson.

- Howe, Admiral (1799), Colleague of Nelson.

- Howard, John (1790), the prison reformer, the first monument erected.

- Lawrence, General (1857), killed in Indian Mutiny.

- Cornwallis, General (1805), fought in American War and in India.

- South Choir Aisle—

- Dean Milman (1868).

- Bloomfield, Bishop (1856).

- Jackson, Bishop (1885).

- Heber, Bishop (1826), of Calcutta.

- Liddon, Canon (1890).

The Crypt contains the Parish Church of St. Faith, Wellington’s funeral car fashioned from captured cannon, and his tomb, Nelson’s tomb (the coffin is made from the wood of one of his ships—the tomb is sixteenth-century work and was made for Cardinal Wolsey), the grave of Wren with its famous inscription, and many illustrious painters sleep in the Painters’ Corner, amongst whom our modern artists Leighton and Millais rest with Reynolds, Lawrence, Landseer and Turner.

Simply beautiful. I hope one day the Americans can build a cathedral that will stand the test of time, and hope it will borrow heavily from the Normans

The Normans? A band of cut-throats who invaded England of the basis of a so-called oath supposedly sworn by the English king, Harold Godwinson. The real reason they invaded England is because it was the richest, most culturally advanced country in Europe. Of course, history paints the English as sloshing around in the mud before the Normans arrived, whereas a factual look at history would reveal a cultured people who created England, gave us the English language and many of the laws and principles we still live by, not to mention the beautiful works seen in such finds as the Sutton Hoo ship burial, the Staffordshire Hoard, etc. . At least the English churches were of a simple, no-nonsense design in which the worship of god was of the most importance, and not the self-aggrandisement of the Norman opportunists who killed thousands of Englishmen and women during their bloody reign – the Harrying of the North being just one example. Anyone who thinks the history of England began in 1066 are not only factually incorrect, they are living in cloud cuckoo land. We had at least over 600 years of English history before that, in which the formation of England, the English people, their culture and language came into being. It certainly didn’t begin with a bunch of Frenchified Viking despots in 1066!

He’s called William the Bastard for more than one reason.

“Of course, history paints the English as sloshing around in the mud before the Normans arrived, whereas a factual look at history would reveal a cultured people who created England, gave us the English language and many of the laws and principles we still live by, not to mention the beautiful works seen in such finds as the Sutton Hoo ship burial, the Staffordshire Hoard, etc.”

That is one reason why we’ve posted so much material concerning Alfred the Great, including this:

https://www.menofthewest.net/the-harp-of-alfred-by-g-k-chesterton/

“A band of cut-throats”

Without a doubt, and yet here we are living in the shadow they cast nearly a 1000 years later.

“Norman opportunists”

As a decendant of one of those Frenchified Viking Despots I will take that as a compliment. We could do with a bit more of that opportunism fielded against our so called elites right now.

“Simply beautiful. I hope one day the Americans can build a cathedral that will stand the test of time, and hope it will borrow heavily from the Normans.”

I will gladly take the beauty of Norman architecture over the deliberate hideousness of any “Crystal Cathedral.”

https://infogalactic.com/info/Norman_architecture

https://infogalactic.com/info/Crystal_Cathedral

It is always astounding to see the difference between the visions of the past with the visions of modernity. A pale mockery of the dreams of old. Now…Wren was a genius on his own level, there is no doubt. But to look around and try to find the sheer audacity and scope of a people that believed in itself in the modern West is…difficult. Present…but difficult.