Editor’s Note: The following comprises the eighteenth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XVIII

It was, I think, on Thursday, 16th April, that it was first realised that the Matabele had really advanced to within a short distance of the town. On that day, information having been received that there was an impi on the Umguza just below Government House, a small force was got together to go out and ascertain the truth of the report. This force consisted of twenty-one Scouts under Captain Grey and twenty-two of the Africander Corps under Captain Van Niekerk, Captains Nicholson and Howard Brown accompanying them, so that there were only forty-five men and officers all told.

Leaving town before daylight on the Friday morning, this little force crossed the stream on this side of Government House just as the sun was rising. It then, after emerging on to the high ground, turned to the right towards the Umguza. Soon numbers of Kafirs were seen moving about in the bush on the farther side of the river, who, when they saw the white men advancing at once opened fire on them, at a distance at first of about 800 yards. This fire was not answered, but as soon as the Scouts and Africanders could be thrown out in skirmishing order, they were ordered to advance towards the river at a canter. On reaching it they at once crossed at two different places, the Africanders being on the right and Grey’s Scouts on the left. When the top of the farther bank was reached the white men found themselves within 150 yards of a number of Matabele advancing rapidly towards them in skirmishing order through the bush. These latter at once fired a volley, all their bullets going high, and then turned and ran as the horsemen came galloping towards them. As Grey’s Scouts got amongst them it was seen that the line of skirmishers was supported by a large body of men some distance in their rear, from which two flanking parties had been thrown out on either side. Van Niekerk charged with his men right on to the head of the left-hand flanking party and drove it back, but Captain Grey with his Scouts, whilst driving in the skirmishers on the main body, passed the right-hand flanking party, which then attempted to cut off his retreat to the river.

At once recognising that the natives were in force, and that the number of men at his command was altogether too small to cope with them, he gave the word to retire, and then both the Scouts and Africanders got back across the river again as quickly as possible, closely followed by the Kafirs. On reaching a rise some few hundred yards on the near side of the river, the white men halted, and dismounting kept the Kafirs in check for a while, but it was soon seen that their numbers were such that they would have been completely surrounded, so, one man and three horses having already been wounded, it was deemed advisable to retire and leave the field for the time being in possession of the Matabele. The wounded man was Mr. Harker, who was shot through the leg, but eventually recovered without losing the limb. The three horses that were wounded all died subsequently.

Upon reaching Bulawayo I at once had interviews with Mr. Duncan and Colonel Napier, and convinced them both that it was more necessary to establish a fort on the road between Bulawayo and Fig Tree than to add one more to the two already existing between Fig Tree and Mangwe, and I then and there received instructions to bring my own troop back again from Matoli, in order to build a fort at Mabukitwani. I should have left the same evening, to rejoin my men and carry out these orders, but the question arose as to the best means of provisioning the garrisons of the various forts, amounting altogether to 180 men. It was most inadvisable that any more food-stuff should be sent out of Bulawayo at this juncture than was absolutely necessary, so as there were three Government mule waggons at different forts along the road, I suggested that these should be sent down to Tati, where I understood that there was a good deal of food-stuff stored, to bring up full loads of the most necessary kinds of provisions, the balance of which, when the garrisons of the forts had been supplied with a month’s rations, could be brought on to Bulawayo. Colonel Napier at once telegraphed to Mr. Vigers, who was in charge at Tati, to ascertain what food supplies he had on hand, and requested me not to leave Bulawayo until an answer had been received. I therefore spent Saturday night in bed, instead of on horseback riding down the Mangwe road. About eight o’clock on the following morning, Sunday, 19th April, a horse came galloping into town riderless, and with its saddle and bridle covered with blood. This horse was soon identified as having belonged to one of three men of the Africander Corps, who had left Bulawayo on picket duty in the neighbourhood of Government House on the preceding evening. It was subsequently discovered that these poor fellows had been surprised and killed by the Matabele early in the morning, two of their horses being also killed or captured, whilst the third made good its escape and galloped back into Bulawayo with a bullet-wound through its neck. The names of the unfortunate men were Heinemann, Van Zyl, and Montgomerie.

The excitement caused by this incident had scarcely subsided when news was received that Colonel Napier’s homestead at Maatjiumschlopay, only about three miles to the south of the town, was being attacked by a large force of Matabele. At this homestead there were a large number of friendly natives, mostly armed with assegais, and also sixteen white men who occupied a small fort which had been built on the top of a small kopje overlooking the farm.

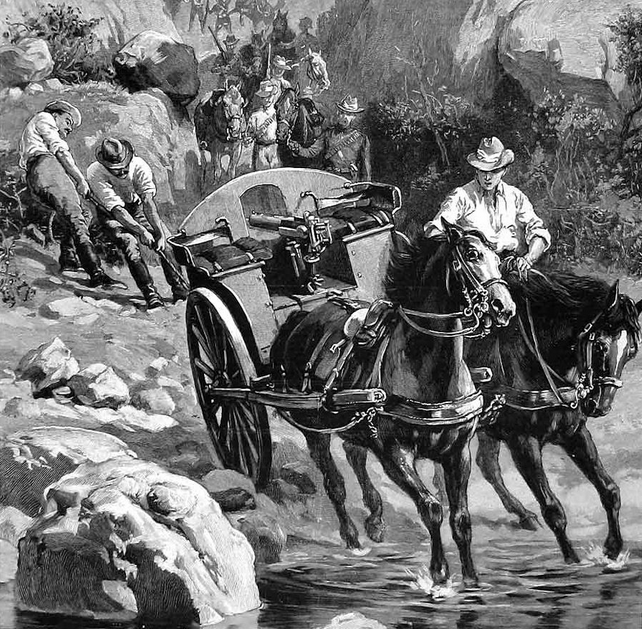

The first news received was that the Matabele had carried off a lot of cattle, killed a large number of the Friendlies, and were now besieging the white men in their fort. A small force of mounted men was therefore hastily got together and sent out to their assistance under Captain Macfarlane. This force consisted of a troop of the Africander Corps under Captain Pittendrigh, a few of Grey’s Scouts, and some men of K troop under Captain Reid; about sixty troopers all told, with a Maxim gun in charge of Lieutenant Biscoe. It left town at about ten o’clock, taking the Tuli road.

At this time I had an appointment with Colonel Napier at his office, to get the answer expected to the telegram sent the day before to Mr. Vigers at Tati. However, on inquiry at the office, I found that Colonel Napier was out, and that no reply had yet been received from Tati. On asking where Colonel Napier was, I was told that he had accompanied Captain Macfarlane. Now I had been requested not to leave Bulawayo until Colonel Napier had communicated to me the contents of the telegraphic message he was expecting from Tati, and therefore, believing that he had gone out with Captain Macfarlane’s patrol, and that I would not be able to make a start for Matoli until he returned, I thought that I might as well take a ride out and see what was going on too.

Major Armstrong very kindly lent me the pony which he had ridden from Mangwe, which I knew was a very steady animal, trained for shooting. It did not take me long to saddle up, and I was soon riding hard on the tracks of Captain Macfarlane’s troopers. I came up with them on the race-course, not far beyond the suburban stands, and learned from the officer in command that the attack on Maatjiumschlopay had been repulsed by the Friendlies, with the assistance of the white men in garrison there. The Matabele had not been in any force, and had evidently intended to sweep off a herd of cattle which was kept on the farm, and which the sixteen white men were there to protect.

No doubt the rebels were ignorant of the presence of these latter, for they cleared off when they were fired upon, hotly pursued by the Friendlies, who overtook and killed six of their number with clubs and assegais.

As these marauders had had ample time to reach the thick bush bordering the Umguza, where they would have been able to scatter and hide, Captain Macfarlane determined to waste no time in pursuing them, but to make a reconnaissance down the Umguza towards Government House, in the hope of coming across a larger body of rebels who would be likely to make a stand.

We therefore crossed the Salisbury road and followed down the bank of a stream which runs into the Umguza some two and a half miles from Bulawayo, just beyond a deserted farmhouse belonging to Mr. Colenbrander. The farmhouse stands on a rising piece of ground, in the angle formed by the two streams, but is about 400 yards distant from the Umguza, though close to its tributary.

When we got near the farmhouse, being still on the near side of the stream we had been following, some Colonial Boys, who proved to be scouts sent out by Mr. Colenbrander, came up and informed Captain Macfarlane that there were a lot of Matabele along the river, and that a number of them had only just left the farmhouse opposite.

The right-hand flanking party, under Lieutenant Hook, had now crossed the stream, so I galloped after them to get a look round from the high ground. Standing near the house, we could see large numbers of Kafirs spread out in skirmishing order amongst the scrubby bush on the farther side of the Umguza. As soon as they saw us, they at once commenced their usual tactics, throwing out flanking parties on either side, no doubt with the idea of surrounding us, whilst at the same time skirmishers were sent forward from the centre, evidently to take up a position in the bed of the river.

At this moment a messenger arrived recalling Lieutenant Hook to the other side of the stream, and upon riding through with him Captain Macfarlane informed me that, having just heard that another impi was approaching from the direction of Government House, he intended to take up his position on a fairly open piece of ground, near the junction of the smaller stream with the Umguza, and let the Kafirs attack him there, his force being altogether too small to risk crossing to the other side.

As we advanced the Kafirs opened fire on us, and a skirmishing fight soon commenced. I was asked to take a few of the Africanders across the smaller stream, so as to keep the Kafirs from taking possession of it, which I at once proceeded to do, but as I thus became separated from the main body I can only give an account of our own little skirmish.

As we rode up the rising ground beyond the stream, some Kafirs sent a few bullets whizzing amongst us from the shelter of the river, and then as we still advanced they very foolishly abandoned a good position and ran up the farther bank, and then along the river in a line, and in such a manner that if the one aimed at was missed, the next was very likely to be hit. The men I had with me were all good shots, and I saw several natives drop to our fire before they got round a bend of the river. Keeping a sharp look-out on ahead, I noticed a lot more coming down from the scrubby bush beyond it and crossing to our side, and rightly divining that their object was to advance up the valley behind the next ridge and then close in on us, I called to the few men with me to gallop at once to the top of the rise to prevent being taken by surprise and fired on from above.

Just at this moment we were joined by Lieutenant Hook and a few more men, and spreading out in skirmishing order, we rode to the top of the rise. We were just in time to meet a number of Kafirs—I daresay fifty or sixty altogether—making for the same position from the opposite side. They were right in the open, the nearest being within 150 yards of us. Some were armed with guns and rifles, but many of them had nothing but assegais and shields.

As soon as we appeared on the rise in front of them they all stopped, and those with rifles fired on us, their bullets nearly all going high, but on two of their number falling they commenced to retreat towards a strip of thickish bush which ran from near the bank of the Umguza river right up behind Colenbrander’s farmhouse. This bush was about 400 yards from the top of the ridge from which the men with me were firing, and from its shelter a number of Kafirs were answering us and covering the retreat of their men across the valley. However, as the horses were quickly taken behind the ridge, and the men showed as little of themselves as possible, their fire did us no harm. On the other hand, several of the Kafirs fell to our shots before they reached the cover of the bush. They made no attempt to run fast, but went off crouching down at a slow trot. I myself was sitting down with my back against a stone, and shooting as carefully as possible, when a bullet struck a small stone close to my left foot and ricochetted with a loud buzzing noise close past poor Pat Whelan, a brave son of Erin, who had been with me on the first patrol to the Matopos, and who, having come out from Bulawayo on this day for the fun of the thing, thought it his duty to keep near me. “That was a fair buzzer,” said Pat.

The Kafirs were now calling to one another, or some one was giving them orders in the bush, and we could see that they were all making up within its shelter towards the farmhouse. Thinking that their idea was to get behind it, and then fire on the position taken up by the Maxim, I gave the word to the men with me to mount and take possession of it first. This we promptly did, just getting there as the foremost of the enemy were about half-way between the bush and the house. They stopped and fired at us as before, and then retired to the bush again, from which they kept up a fusillade on the house, which, however, unless they had made a heavy rush, we could have held against them if necessary; but just then Lieutenant Moffat came up with a message from Captain Macfarlane, requesting me to retire on his position and endeavour to draw the Kafirs on to the Maxim.

As we withdrew from the house they at once came on out of the bush, and when we got down to the stream they were already firing at us from behind it, and, their advance not being opposed, some of them came right down into the bed of the stream.

At this time there was a really good chance for the Maxim to do some execution, for although the Kafirs were nowhere in masses, there was a straggling line of a couple of hundred of them right out in the open, and not more than 400 yards from the gun. But when the word was given to fire it most unfortunately jammed at the sixth shot, and the Kafirs had to be driven back by rifle fire. The cause of the mishap was that a cartridge-case had broken off at the rim in the barrel of the Maxim, rendering it for the time being useless. The natives now again commenced to try and get round us on both sides, and it being reported that the other impi was advancing from the direction of Government House, Captain Macfarlane gave the word to retire.

At this time I was with Captain Reid and the men of his troop, helping to keep the Kafirs from crossing the Umguza at a point where they were trying to do so a few hundred yards below us, and it was here that a man named Boyes, of the Africander Corps, was killed. He, with another man, seems to have gone down close to where the smaller stream joined the river, and was shot from the cover of the bank right through the chest, his horse being shot at the same time I think. He fell dead at once, and his companion galloped back to the main body.

Captain Macfarlane was already retiring, and the order had come to Captain Reid to do the same, acting as flanking party to the right of the main body. Unfortunately, the death of Boyes was not reported to the commanding officer until the patrol was half-way to Bulawayo, so that the poor fellow’s corpse fell into the hands of the Kafirs. The only other casualty was one man badly wounded in the knee. Considering the number of bullets that pass pretty near to every one engaged in a small skirmish such as I have described, it is wonderful how few men get actually hit. The fact seems to be that in a running fight, when they are flurried and hustled, Kafirs cannot get the time they require to take good aim, and if you are near them they always shoot over you. The golden rule is to scatter out, each man firing independently in the Boer fashion.

But although Kafirs shoot very badly if hurried and kept moving, many of them are very fair shots if they can get all the time they require for aiming, as they can in hilly country, where they can take up positions behind rocks, from which they can fire at their enemy at their leisure and without exposing themselves.

On the day of which I have been speaking, some of them with whom my little advanced party was engaged were firing at us with some very peculiar bullets, which I think had probably been made by first putting a stone into the mould, and then pouring lead on to it, forming a very rough irregular projectile. At any rate you could hear these bullets coming on with a loud buzzing noise, which increased in intensity until they passed with a peculiar whizzing sound. The trouble was one did not know which way to dodge, for as you could hear them approaching but could not see them, it would have been as easy to dodge into one as out of its way.

As our small force retired the bush became more and more open, so the Kafirs made no attempt to follow us. I do not think that they realised that the Maxim was out of order, and if not they probably thought that the retreat was a ruse to draw them into more open ground. What their losses were it is difficult to say, but I think that the small advance party to which I had attached myself could not have killed less than twenty; indeed, I think I saw quite that number fall. My friend Pat Whelan had fired away almost all his cartridges, and on examining my belt I found that I had nineteen less than I came out with.

However, the Kafirs again retained their position, and it was evident that their numbers were so great—we having only engaged their advanced skirmishing line—that it would not be safe to cross the Umguza and attack them on their own ground without a considerable force, both of foot and horsemen; the latter to work in the more open ground, and the former to drive them out of patches of bush.

Before returning to Bulawayo, Captain Macfarlane took a sweep round across the open ground in the direction of Dr. Sauer’s house, and we there came in sight of the impi which had been reported early in the day. The main body was standing in a dense black mass on the top of a ridge just below Government House, their skirmishing lines being thrown out on either side, and in advance of the centre. Now the fact that this impi had stood idly by, not exactly watching, but at any rate listening to the firing that had been going on during the skirmish between their compatriots and the white men, shows, I think, the extraordinary want of combination amongst them, of which I have before spoken, and which has been one of the features of this campaign.