Editor’s Note: The following comprises the supplementary, and final, chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

SUPPLEMENTARY CHAPTER

CONTAINING A FEW THOUGHTS AND OPINIONS ON MATTERS RHODESIAN AND SOUTH AFRICAN

No one, I think, who has carefully read the little history which I have just brought to a close, can fail to have been struck by the conspicuous part which has been played by the Dutch settlers in Matabeleland in the recent struggle for supremacy between the white invaders of that country and the native black races; and it will probably come as a surprise to many to find that the Boer element is so strong as it is in Rhodesia, for that country has always been considered more exclusively British as regards its white population than any other State in South Africa, not except Natal and the Eastern Province of the Cape Colony, both of which territories, though almost purely British in the large towns, yet possess a large Boer population in the farming districts, whose ancestors were living on the land before the arrival of the British colonists.

But, in the opening up and colonisation of Rhodesia by means of the pioneer expedition of the British South Africa Company, which took possession of Eastern Mashunaland in 1890, a new departure was made in South African history, for the British became the pioneers instead of the Dutch, and a British colony was established in the far interior of the country many hundred miles to the north of the most northerly Dutch state; and it is the fact that the occupation of Mashunaland in 1890 and the invasion and conquest of Matabeleland in 1893 were purely British enterprises, which has, I think, created the belief generally held in England that Rhodesia at the present day is a purely British colony. Yet this is not the case, for within the British state there are two Boer colonies, the one of which has been established subsequent to the Matabele war in the country to the south of Fort Charter, whilst the other has occupied the hills and valleys of Gazaland since the latter part of 1891. Besides these agricultural colonies, where a number of contiguous farms are occupied by Boers who have settled on the land with their wives and families, there are many other Boer farmers scattered throughout Rhodesia, whilst up to the time when the rinderpest destroyed all their cattle, a large number of Dutchmen were constantly present in the country, earning their living with their waggons and oxen as carriers from one district to another.

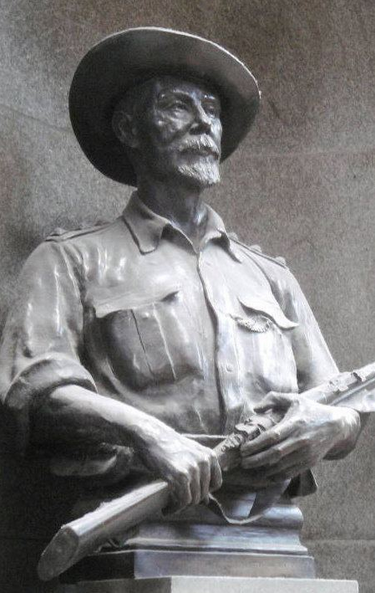

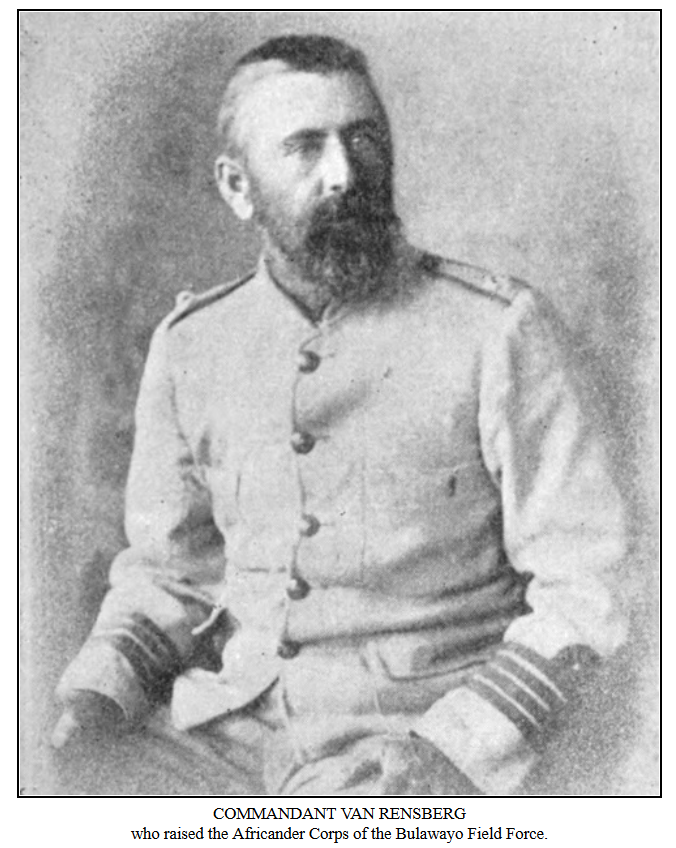

When the rebellion broke out, Commandant Van Rensberg at once formed an Africander Corps, the great majority of whose members were Boers, although it numbered in its ranks a certain proportion of colonists of British blood, and it is a matter of history that these Dutchmen under Commandant Van Rensberg and Captains Van Niekerk and Pittendrigh have done splendid service during the recent insurrection in Matabeleland, and have fought side by side with Grey’s Scouts and Gifford’s Horse, and all the other troops of the Bulawayo Field Force, in a way which has won for them the admiration and respect of their brothers in arms and fellow-colonists of British blood; and that the mutual esteem and good fellowship engendered between the two races during the recent time of common peril may be fostered and maintained in the coming years ought not only to be the earnest desire of all thinking men, but should be also one of the main objects constantly kept in view by the English Administrator of these territories.

Many years ago, at a time when the scheme for the colonisation of the high and healthy plateaus lying between the Limpopo and the Zambesi had not yet assumed definite shape in the fertile brain of Mr. Cecil Rhodes, I remember writing in the course of an article, published, I think, in the Fortnightly Review, that those territories were in my opinion the natural heritage of the British and Dutch colonists in the older states of South Africa. My forecast was true enough, for although in its first inception the colonisation of Rhodesia was a purely British enterprise, yet to-day, in less than six years from the date when the Union Jack was hoisted at Fort Salisbury and the country proclaimed to be a province of Britain, it already numbers amongst its inhabitants a very considerable number of Dutch Boers, who form an element of the population, which in all South African history has been found indispensable for the gradual conversion of vast uncultured wastes into civilised states.

Now I might, I think, have gone further, and said that the whole of temperate South Africa (in which must be included the high plateaus lying between the Limpopo and the Zambesi) was the joint possession of the British and Dutch races; for in all the states of that country, the old and the new alike, we find the two races living side by side, whilst, curiously enough, in the British province of the Cape Colony the Dutch outnumber the British, and in the Boer State of the Transvaal the British outnumber the Dutch.

Throughout South Africa the Dutch live away from the towns on their farms, and, speaking generally, form the agricultural and pastoral population of the country. They are naturally a kindly, hospitable race; but as the inevitable result of their surroundings and the circumstances in which they have lived for generations, they are for the most part very poorly educated, and therefore ignorant, unprogressive and bigoted; whilst among the descendants of the “voor-trekkers,” who some forty years ago abandoned their farms in the Cape Colony and fled, with their wives and their children, their flocks and their herds, into the unknown interior beyond the great Orange River, in order to escape from what they considered the injustice of British rule, there exists an ingrained hatred and distrust, not of the individual Englishman, but of the government of the country under whose flag they believe their fathers suffered wrong, and it is this sentiment which at the present moment, unfortunately, is being used as a political lever, which threatens nothing but disaster to the whole of South Africa, by the anti-British, but non-Boer adventurers, who are fighting for their own hands in Pretoria.

The recent deplorable invasion of Transvaal territory by a British force in defiance of all international law, to accomplish I still fail to understand what, has naturally exasperated the Dutch of the Transvaal, and caused them to look upon everything British with more distrust and suspicion than ever; but the history of that disastrous expedition, evoking as it did the most intense national sentiment, not only amongst the Boers of the Transvaal, but also in a somewhat milder degree perhaps, though still in a most pronounced manner, amongst their compatriots in the Orange Free State, coupled with the very notorious fact that in the exclusively Dutch districts both of the Cape Colony and Natal a very strong anti-British feeling was excited, must have convinced even the most infatuated that a conflict between Dutchmen and Englishmen, in whatever portion of South Africa it may arise, will be but the prelude to a war between the two races throughout every province from Cape Agulhas to the Zambesi—a war which would retard the general progress of the country for a generation, which would be infinitely disastrous to both races engaged in the struggle, and yet could be beneficial to neither, no matter which proved victorious.

In future let us hope that neither young military aspirants to fame, who, being ignorant of everything concerning South Africa, would yet climb their way to glory over the dead bodies of British and Dutch South Africans with the most light-hearted carelessness, just in the way of their professional business, nor cold-hearted self-seeking foreign politicians, who would use the ignorance and prejudice of the Boer to assist them in gratifying their jealous hatred of England, will be allowed to sway the councils of the statesmen, British or Boer, on whose decree the fate of South Africa really depends.

Not being a politician nor anything else but a wandering Englishman with a taste for natural history and sport, it may be held most presumptuous on my part to have written as I have done; but yet I have the most profound conviction that a war between the Boers and British in South Africa can only be a calamity of incalculable dimensions to both races; whilst the name of that statesman, whether Boer or Briton, who should without just cause on the one hand “cry havoc and let loose the dogs of war,” or on the other compel the slipping of such dogs by fatuous obstinacy, and a cynical disregard for all the principles of enlightened government, will be assuredly held in execration by unborn generations of Boers and Britons alike. Neither race can get away from or do away with the other, and therefore both must try and rub off their mutual prejudices, and live harmoniously together.

This is not difficult in a new country like Rhodesia, where the representatives of the two peoples are in the nature of things thrown much together, and where there has always been a good understanding between them, which has of late been very much strengthened by the mutual assistance given by each to the other during the recent troublous times; and the fact that in these territories a very good understanding prevails between the Dutch and British gives one reason to hope that in time a similar state of things may be attained in the Transvaal, although unfortunately in that State there are several factors which militate against such a result being speedily arrived at.

In the first place, the great mass of the European population in the Transvaal, the greater part of which is British, resides in one great city, where it leads its own life, and does not come in contact with the Dutch farming population, of which it knows neither the language nor the history, and with whose modes of thought and manner of life it is altogether out of sympathy; whilst, on the other hand, the rough Boer, in too many cases, despises the ultra-civilised, sharp-witted, faultlessly-dressed European, and does not recognise that many amongst them are fine fellows and good sportsmen, and are capable of throwing off their coats and doing a day’s work, hunting or fighting, with the roughest Boer amongst them, should occasion serve.

And yet these mutual prejudices and misunderstandings between the two peoples might easily be rubbed away if it were not for the presence of an anti-British clique of Hollanders and Germans in Pretoria, whose object it is to widen the breach between the Boers and the British; and as many of these men occupy official positions in the Government of the country, and are therefore more in touch with the Boer legislators than the citizens of Johannesburg can hope to be, they have opportunities which they do not fail to use of increasing the distrust and suspicion already existing between the two races who alone have got to work out the destiny of South Africa between them, and amongst whom they are only meddlesome self-seeking interlopers.

All the various States of South Africa will no doubt be united sooner or later under one flag, but I am beginning to have my doubts as to what flag that will be. It is true that at the present time there exists in South Africa a very large British population of highly intelligent and energetic men, who have been attracted to that country by the diamond and gold fields. That population is constantly increasing, but it is not one which settles on the land. It is rather a population which has come to the country on a visit, in the endeavour to make a fortune with which to retire to the old country, and as the recent census taken in Johannesburg has shown, it is for the most part composed of young men, the greater number of whom are unmarried. Now I suppose it is conceivable that a day may come, say in fifty, eighty or a hundred years time, when all the treasures have been dug up out of the South African earth; and should such a day arrive, is it not also conceivable that the great mining populations which have built the cities of Kimberley and Johannesburg in what a few years ago was a sparsely-inhabited wilderness, may dwindle down to comparatively small proportions, leaving the Boer population, which during all that time will have been increasing at a very rapid rate, once more numerically very much in excess of the British?

It does not appear to me very probable that during the present generation at least the Boers, either of the Transvaal or the Orange Free State, are likely (except under compulsion, which presupposes a deplorable war) to enter any confederacy of South African States, on any terms whatever, under the British flag; and therefore should the large British mining population now existent in the country gradually vanish, and the Boer population at the same time very much increase, the eventful confederation may take place under some other flag than the Union Jack. After all, as the Boers hold as large a stake in land, if not in wealth, as the British in South Africa, and as they were the first comers, and can lay claim to having killed off as many natives, and generally prepared as much country for occupation by white men, as the British, I think they are entitled to some consideration in the matter of the flag which is eventually to fly over the confederated States of South Africa; and for my part I would rather see a confederation take place under a compound flag, composed of equal parts of the Union Jack and Dutch ensign, with a bit of a French flag let in, to represent the Huguenots who, on their first arrival in South Africa, formed one-sixth of the entire white population of the country, and to whom the South African Boers of to-day owe many of their most estimable qualities, than have the country plunged into war in order to enforce its acceptance of the Union Jack.

However, this flag question is a problem of the future, and in the meantime it is the duty of all South Africans who have the welfare of the country as a whole at heart to do all they can to obliterate the remembrance of events galling to the national pride either of Dutchmen or Englishmen, and to endeavour to bring about once more a feeling of mutual trust and confidence between the two races. The Dutch must forget Slagter’s Nek and Boomplaats, and the English must learn to think no more of avenging the defeats of Laing’s Nek and Majuba Hill than they do of avenging the battles lost by the British troops in America which culminated in the surrender of Cornwallis and the declaration of American independence.

Now there has been for some years past an association in South Africa called the African Bond, which in some quarters at least must be considered anti-British, since another association called the Loyal Colonists’ League has been inaugurated to counteract its effects. This latter society, judging by some speeches which have lately been made by some of its members, is frankly anti-Dutch. Now, would it not be better, if, in place of the latter society, whose object seems to be to widen and accentuate the breach which, in the Transvaal at least, is existent between the two races, an association should be formed, which all clergymen of all denominations, including ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church, should be invited to join, whose object should be the gradual obliteration of race-hatred and race-jealousy between the Dutch and British throughout South Africa, by the promotion of knowledge amongst the ignorant and prejudiced of both peoples?—for that, after all, is what is most required in order to bring about mutual respect and mutual forbearance, and enable every member of every State in South Africa to work under equal laws for the general prosperity of the whole country, a prosperity which can never attain to full fruition until the Dutch and British have attained to a political unity throughout South Africa as complete as it is to-day in the Cape Colony.

And now, after this long digression upon matters South African, and the expression of many opinions which, should they be read at all, will possibly only excite ridicule, coupled with a rebuke upon my presumption in wandering from the fields of sport and natural history, where I may be at home, into the arena of politics, where, it will be said, I certainly am not, let me say a few words about the present position and future prospects of Rhodesia.

Should the lists I have given at the end of my book be glanced through, it will be seen that the number of the settlers who were murdered in Matabeleland alone at the outbreak of the native insurrection, added to those who have since been killed and wounded in the subsequent fighting, amounts to over 300, or more than ten per cent of the entire white population of the country at the time of the outbreak of the rebellion, a proportion, I think, which ought to be entirely gratifying to even the most determined enemies of colonial expansion in Africa, whilst it gives the lie direct to the statement which has so frequently been made, that the settlers in Matabeleland have run no greater risks in fighting with the Matabele in order to put down the rebellion than would be incurred by a sportsman engaged in shooting hares and rabbits at home.

I do not expect that the publication of these lists will call the blush of shame to the cheeks of those who have been so eager to vilify their countrymen in Rhodesia, but I do hope that it will arouse a feeling of indignation in the minds of many who have hitherto been more or less led astray by these dishonest, spiteful, and unpatriotic mentors, and at any rate they must be sad reading to all but the most prejudiced. However, the rebellion can now, I think, be considered as almost at an end. The Kafirs have entirely failed in their attempt to kill all the white men in Matabeleland, and to re-establish themselves as an independent nation. To the west, north-west, north, north-east, and east, the impis which four months ago had formed a cordon round all those faces of Bulawayo have one and all been driven from their positions, and have now broken up into hundreds of little bands, living in the forests with their wives and children. From all the information one can gather, the vast majority of these people are already suffering from want of food, as their cattle are all or nearly all dead from rinderpest, and a large proportion of their year’s supply of grain has been taken possession of or destroyed by the white men. Under these conditions they cannot hold out much longer, and they would probably have already come in to surrender were it not that on the one hand, knowing the exasperation caused amongst the whites by the crimes they have committed, they are afraid to throw themselves on their mercy, and on the other they are kept from doing so by their chiefs, who having been the ringleaders of the rebellion, and fearing that in case of surrender their own lives at least would be forfeited, are still doing all they can to prevent their people from submitting.

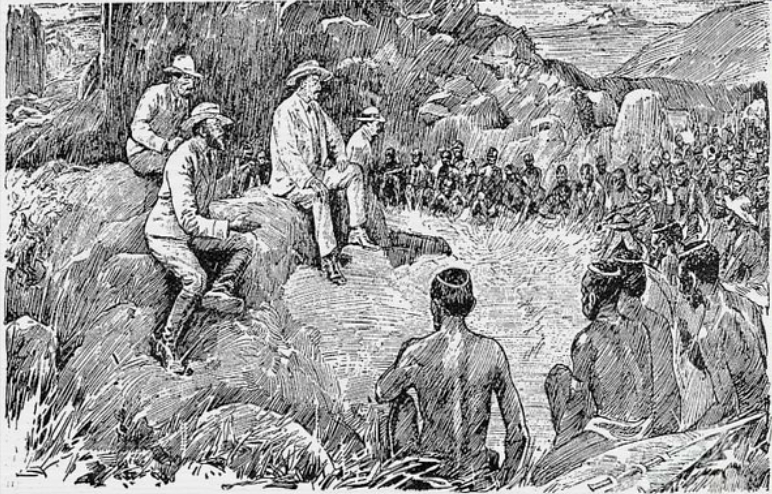

In the Matopos, Mr. Cecil Rhodes and Mr. Johan Colenbrander are at the present moment carrying on negotiations with the insurgent chiefs, which may or may not end in peace. Should no satisfactory arrangement be arrived at, and the war be continued, the natives will be driven to desperation, and it will not only require a much larger force than there is at present in the country, but the expenditure of a vast amount of money, and the loss of many valuable lives, before they can be absolutely all killed or hunted out of the almost impregnable fastnesses and hills honeycombed with caverns which exist all over the large area of country known as the Matopos.

Now I think that, in view of the enormous cost and great loss of life that would be entailed by the decision to make no terms with the natives, it would be better to accept their submission on lines consistent with the future safety of the country. The chiefs must stand their trial, but the lives of all those who have had no part in the murder of white men, women, and children, could be guaranteed. The whole nation must of course be disarmed as completely as possible, and the actual murderers of white people during the first days of the rebellion must be shot or hanged. But should these conditions be complied with, whilst at the same time a large police force is maintained in the country, and the native administration carried on in such a way that, although the natives are treated with firmness, their grievances will always be heard, and as far as possible remedied, I do not think we need fear another rebellion.

Of course there are those who say that it is a great mistake to hold any parley with them at all. Go on killing them, they say, until the remnant crawl in on their hands and knees and beg for mercy. Well, that end could only be attained, as I have already said, at a cost of much money and many lives; so I think that there are many here, who, some for the sake of expediency and others for the sake of humanity, would now wish to see this rebellion ended as soon as possible, if it can be done in such a way as to ensure the future safety of the settlers in the country. As soon as the chiefs submit and their people are again located on the lands from which they have been driven, I think there can be no doubt that the country will, for the time being, be perfectly safe for white men; for history has shown us that when a Kafir tribe submits it does so absolutely for the time being, and no murders of isolated individuals are committed until the chiefs are ready for another insurrection.

It may of course be said that the Matabele have not yet been thoroughly beaten, and that, having gained a good deal of experience during the last five months, their idea in submitting is to get in their next year’s crops and then begin again, on the principle of “reculer pour mieux sauter.” But is this at all probable? After the first war they were more or less surprised into submission to the white men, the greater part of them never having fought for their country at all. Then they found that the shoe of the white man’s rule began to pinch, but they wore it for two years, and did not attempt to throw it off until the country appeared to them to have been left in an absolutely defenceless condition by their conquerors.

They have now had their rebellion, and it has absolutely failed, and they have lost at least twice as many men in the recent fighting as they did in the first war. Nor is there any longer a cattle question to excite their resentment, for the cattle are all, or almost all, dead from the rinderpest. Therefore it appears to me, that if they are disarmed as far as is possible, and if a strong police force is maintained in the country for the next few years, their submission can be safely accepted, and the mass of the people be allowed to go unpunished; but justice and common sense both demand that all who are proved to have been implicated, either directly or indirectly, in any of the murders which marked the outbreak of the rebellion, shall be most summarily dealt with. They will be gradually discovered, and some, it may be, may not be brought to justice for years to come, but no mercy must be shown them whenever or wherever they may be found.

In less than two years’ time the railway now being pushed on through the Bechuanaland Protectorate will have reached Bulawayo; and if the natives can be kept quiet by a firm and just rule until the advent of the iron horse in Matabeleland, there is little fear of their ever again rising in rebellion against the white man.

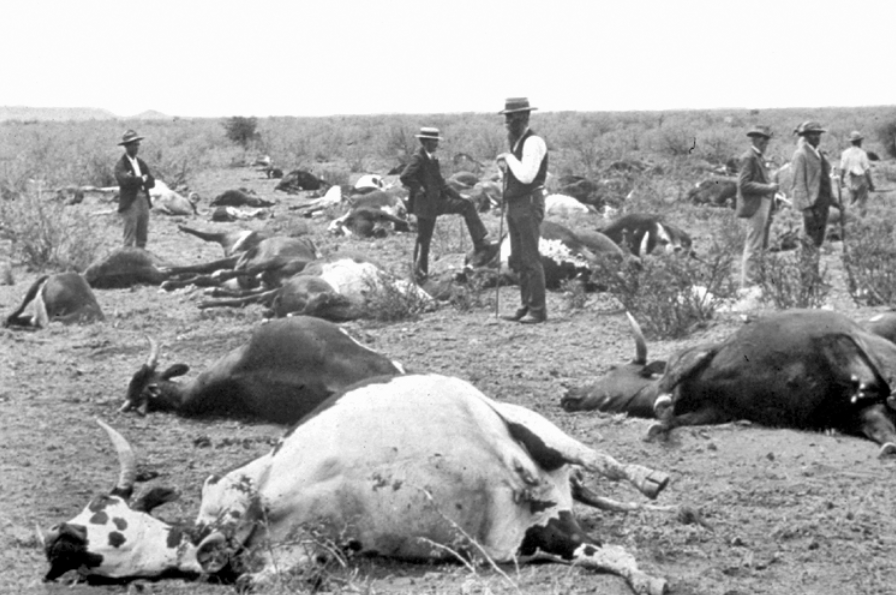

In the meantime the development of the country must remain at a standstill, and the country retained as a British possession, by an occupation which will be almost purely military, as not only has the cost of living been rendered almost prohibitive through the destruction of all the cattle in Matabeleland and Bechuanaland by the rinderpest, and the consequent substitution of mules and donkeys in the place of oxen for draught purposes, but farming also has been rendered very difficult, as, putting aside stock and dairy farming, no ploughing can be done without oxen, nor can agricultural produce be carried to market without the assistance of those useful animals, for salted and acclimatised horses and mules are too scarce and expensive to be reckoned on for farm work. The rinderpest, therefore, has for the present put an end to all European enterprise in the way of mining and farming in Matabeleland.

People in England can only realise the disastrous effect which this dread disease has had on the prosperity of the country by endeavouring to picture to themselves what the consequences would have been had a disease suddenly made its appearance in Great Britain in the early part of the present century, before the introduction of railways, which destroyed ninety-nine per cent of all the horses in the British Isles; yet even that would scarcely represent the extent of the calamity from the effects of which we are now suffering, when it is considered what an immense tract of barren wilderness yet lies between Matabeleland and the nearest railway station.

In the early part of this year there were over 100,000 head of cattle, all sleek and in excellent condition, in Matabeleland, but when it closes, I think it very doubtful if 500 will be still left alive in the whole country. Even this loss is small as compared with that sustained by Khama and his people, who were the largest cattle-holders in South Africa, and whose loss it has been computed, from reliable data, exceeds 800,000 head of horned cattle.

However, the rinderpest is a calamity which is not likely to occur again, but which, when it does occur, sweeps everything before it both in Europe and Africa. That Matabeleland as a whole is a country second to none in South Africa for cattle-breeding is the opinion of everyone who has lived there for any length of time and had the opportunity of studying the matter. When, therefore, the rinderpest has died out, and the railway has reached Bulawayo, the country will be gradually restocked; and then, too, mining machinery will be imported, and our mines will at last be worked with a result which will give the final death-blow to all those who have for the last six years been engaged in disseminating falsehoods concerning Rhodesia.

From the statistics supplied to me by the Compensation Board, which I have given in the form of an appendix, it will be seen that a good deal of farming work had already been done at the time of the outbreak of the rebellion, and that the population of Matabeleland were not all “gin-sellers” or “men who had gone out to Matabeleland in order to swindle the British public, by inducing them to subscribe for shares in worthless companies, whose so-called gold claims contained no gold.” The fact, too, that farmers and prospectors were living all over the country in perfect health rather explodes the theory of a noxious vapour rising to some four feet from the ground which is so deadly to Europeans that all colonisation of the country is impossible; but this, if I remember aright, was the theory propounded by one of Mr. Labouchere’s “reliable” correspondents—a fit contributor, forsooth, to the pages of Truth.

It is now known throughout South Africa that Matabeleland and Mashunaland are white men’s countries, where Europeans can live and thrive and rear strong healthy children; that they are magnificent countries for stock-breeding, and that many portions of them will prove suitable for Merino sheep and Angora goats; whilst agriculture and fruit-growing can be carried on successfully almost everywhere in a small way, and in certain districts, especially in Mashunaland and Manica where there is a greater abundance of water, on a fairly extensive scale.

As for the gold, there is every reason to believe that out of the enormous number of reefs which are considered by their owners to be payable properties some small proportion at least will turn up trumps, and, should this proportion only amount to two per cent, that will be quite sufficient to ensure a big output of gold in the near future, which will in its turn ensure the prosperity of the whole country.

Once let the railway reach Bulawayo, and given intelligent legislation in the best interests of the settlers and miners in the country, Rhodesia will soon prove its value to the most sceptical; but the prosperity which I predict will, I am afraid, be very much retarded, if not completely destroyed, by the revocation at the present moment of the Charter which was granted to the British South Africa Company in 1889, and the substitution of Imperial rule for the present form of Government. For this reason:—Under the present régime the Company’s administrator is always accessible to the people living in the country, and whatever local reforms may be deemed necessary by the latter are always capable of discussion, and can be acceded to by him on the spot, without despatches having first of all to be forwarded to the High Commissioner at the Cape, by whom they would be sent on to the Colonial Office, with the result that a local reform, urgently required, might be delayed for months or never granted at all.

Under the Company’s government, too, the administrator himself would always be a man acquainted with the history of the territories he was governing, and would be probably one who not only had the prosperity of the country he was governing deeply at heart, but who also would have a very good idea as to how that prosperity was likely to be attained. During the next few years, too, which will be a very critical period in the history of Rhodesia, such an administrator would always have the benefit of the advice of the man through whose energy and genius the territories forming that state have been secured for the British Empire. But should this territory be converted into a Crown colony and governed from Downing Street on hard-and-fast lines, some of them not at all applicable to local requirements, with an administrator very likely ignorant of his local surroundings, and possibly out of sympathy with the settlers—Dutch and British—who have made the country their home, nothing but disaster is to be expected.

Surely the people who have stuck to Rhodesia through good and evil times, and who, under the auspices of the Chartered Company, have added a vast territory to the British Empire and laid the foundations of what will soon be a prosperous colony, which, given an intelligent and adaptable form of government, will be able to pay its way, ought to have some say in this matter, and not be transferred unwillingly to a rule which they know would be ill suited to local requirements, and under which local enterprises would surely languish for want of the fostering care which only a local administrator can provide.

The white population of Rhodesia have had many a growl at the government of the Chartered Company, but in most cases they have got what they growled for—to wit, the extension of the railways, both from the Cape Colony and the East Coast; the reduction of the Company’s percentage of interest in the mines; and full and most generous compensation, where the claims were just, for cattle destroyed in the endeavour to stay the progress of the rinderpest, and for all losses sustained owing to the late native insurrection. Under Imperial rule they know that no compensation has ever been granted for losses sustained through a native rebellion, and they also know that little or no assistance could be hoped for in the construction of railways or other public works. Recognising all these things, having as an object-lesson just before their eyes the wretchedly slow progress made in Bechuanaland under the Imperial administration, and knowing, moreover, that the Transvaal war of 1880-81, if not the loss of the Transvaal itself as a British possession, was brought about solely by a Government from Downing Street, through an administrator entirely ignorant of local requirements and absolutely out of sympathy with the people he was chosen to govern, can it be wondered at that at a recent meeting of the Chamber of Commerce in this town, the people of Bulawayo expressed confidence in the government of the Chartered Company and in Mr. Cecil Rhodes, representing as they do a corporation of capitalists who hold the largest financial stake in the country, and whose aims and objects are identical with those of the people living in the country, whilst they resented the idea of being handed over to Imperial rule without having their wishes in the matter consulted, in order to please the Little Englander party at home?

One of the most noteworthy features at the meeting to which I have referred was the remarkable unanimity shown by the British and Dutch on this subject, for the Dutch up here believe in Mr. Rhodes, and have the most absolute confidence in his ability to insure the prosperity of the country. The natives, too, as has just been shown, look upon him as their father; and I believe that through his influence and the strength of his personality, a peace will soon be arranged with them, which would have been impossible at the present time but for his presence in the country.

Bulawayo, 26th August 1896.