Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Vignettes of Military History (US Army Military History Institute No. 69, April 18, 1977).

The outcome of battles is often credited to great general and crack units. Such leaders and forces do play a major role. Yet small outfits – some organized, some makeshift – even lone soldiers or officers make major contributions, too. These forgotten men receive no glory in their own time and little mention in history. Some such men were the GI’s and junior officers who tried to contain the initial German breakthrough in the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. The following passage is from the contributor’s book THE ARDENNES: BATTLE OF THE BULGE, in the series U.S. ARMY IN WORLD WAR II:

On the morning of l6 December General Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps had a formal corps reserve consisting of one armored combat command and four engineer combat battalions. In dire circumstances Middleton might count on three additional engineer combat battalions which, under First Army command, were engaged as the 1128th Engineer Group in direct support of the normal engineer operations on foot in the VIII Corps area. In exceptionally adverse circumstances, that is under conditions then so remote as to be hardly worth a thought, the VIII Corps would have a last combat residue – poorly armed and ill-trained for combat – made up of rear echelon headquarters, supply, and technical service troops, plus the increment of stragglers who might, in the course of battle, stray back from the front lines. General Middleton would be called upon to use all of these “reserves.” Their total effect in the fight to delay the German forces hammering through the VIII Corps center would be extremely important but at the same time generally incalculable, nor would many of these troops enter the pages of history.

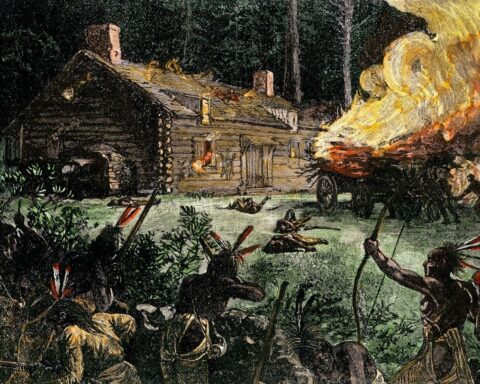

A handful of ordnance mechanics manning a Sherman tank fresh from the repair shop are seen at a bridge. By their mere presence they check an enemy column long enough for the bridge to be demolished. The tank and its crew disappear. They have affected the course of the Ardennes battle, even though minutely, but history does not record from whence they came or whither they went. A signal officer checking his wire along a byroad encounters a German column; he wheels his jeep and races back to alert a section of tank destroyers standing at a crossroad. Both he and the gunners are and remain anonymous. Yet the tank destroyers with a few shots rob the enemy of precious minutes, even hours. A platoon of engineers appears in one terse sentence of a German commander’s report. They have fought bravely, says the foe, and forced him to waste a couple of hours in deployment and maneuver. In this brief emergence from the fog of war the engineer platoon makes its bid for recognition in history. That is all. A small group of stragglers suddenly become tired of what seems to be eternally retreating. Miles back they ceased to be part of an organized combat formation, and recorded history, at that point, lost them. The sound of firing is heard for fifteen minutes, an hour, coming from a patch of woods, a tiny village, the opposite side of a hill. The enemy has been delayed; the enemy resumes the march westward. Weeks later a graves registration team uncovers mute evidence of a last-ditch stand at woods, village, or hill.

4

Mr. Mantel, having read so much of history, what are your thoughts: are battles made or lost in the heroic moments that are recounted for history, or are these moments merely the ones recorded afterwards to make sense of the chaos of minutia described above?

I’d say it depends on the battle. At Cannae you see the former: Hannibal so thoroughly out-generalling the Romans that no action by a few legionaries would have made a difference. In the 1945 Siege of Budapest, it’s more the latter: no distinguished commanders (apart from Malinvosky and Tolbukhin) or decisive maneuvers by illustrious units, just drawn-out, grinding slaughter and exhaustion.

Thats fair. Thoughts on a shift in modern times with general doctrine dictating action is chosen by individual squads or men? Will the historical reliance on generalship and quality fall to the wayside, and more examples like Budapest become prevalent?

4.5