Editor’s note: The following episode from the Second Opium War is extracted from Heroes of Britain in Peace and War, by Edwin Hodder (published 1892).

The scene now is in the town of Tang-ku, in China, and the year 1860. Sir Hope Grant, the Commander-in-Chief of the English army, has determined to attack the Taku Forts, where only a year before our arms had received a terrible repulse. Sir Robert Napier, afterwards Lord Napier of Magdala, commanded the Second Division. A force of 2,500 English and 1,000 French was appointed for the work, and on the day after the announcement was made they left Tang-ku, and making their way through swamps and mud and slush, all the time under a heavy fire from the enemy, took up their position for the next day’s assault.

Early in the morning the advance commenced, and hardly had they proceeded any distance before they heard a heavy cannonading, which announced to Napier that English gun-boats had already opened an attack from the other side. Then his batteries opened fire, and John Chinaman had a warm time of it. Still our men pushed on; a detachment of Marines brought up pontoons to bridge over the deep and broad ditches, and as this had to be done under matchlock fire, sixteen of the poor fellows perished.

The fort was a large work enclosed with a wall or embankment, protected with upright bamboo spikes firmly planted in the earth, and surrounded by two broad moats or ditches. No progress could be made until the spikes were removed, and as this had to be done under a heavy fire, many lives were sacrificed. Then came the formidable ditches; the pontoon bridges were fanciful things, and, as usual with such inventions, were found to be useless in the critical moment; so, as a last resource, the Marines and coolies jumped into the water with their scaling-ladders, and placing these on their shoulders, constituted themselves the “human piers of a bridge,” over which our men crossed safely. The second ditch was crossed in a similar manner, the fire of the enemy being all the while incessant, but at length Napier and his men stood before the crenellated wall of the fort.

Almost as soon as our men began to assail the strong position before them, Ensign Fraser, who carried the Queen’s colour of the 27th Regiment, was severely wounded, and fell.

“Struggling on, with sword in one hand and colour-staff in the other . . . and shouting aloud the cry of ‘Victory,’ (he) was waving his flag aloft, when he was shot down”.

“Struggling on, with sword in one hand and colour-staff in the other . . . and shouting aloud the cry of ‘Victory,’ (he) was waving his flag aloft, when he was shot down”.

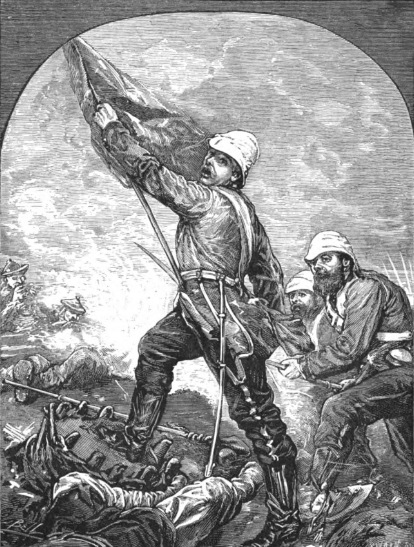

Ensign John Worthy Chaplin, a mere lad, stood next for the duty, and seizing the falling colour, bore it aloft, and, grasping in his other hand a sword, pushed forward. Almost at the very moment he did so the magazine within the fort exploded with a fearful concussion, a live shell from our artillery having been planted in its midst. The first thought was that the work was done, and that there was no fort now to be taken; but after a short pause the fire of the enemy re-commenced with tenfold vigour, and inflicted terrible damage.

The order to advance was sounded, and away plunged young Chaplin to the front. But he had not gone far before he received a shot through the arm. Instead of going to the rear, as he would have been thoroughly justified in doing, he hastily bound up his wound, and refusing to relinquish his colour or move a step to the rear, dashed on again at the head of the regiment. It was his ambition to plant the English flag upon the fort before the French colour should find its way there; and when he came to the perilous bridge across the moat he bounded forward, at the same time challenging the French officer to beat him in the race.

The scene at the foot of the fort was indescribable; the escalading ladders were being placed in position, and up them, in the midst of noise and smoke and confusion, each was trying for himself to climb the walls. Among those who succeeded was Captain Prynne, of the Royal Marines, who no sooner reached the top than, sitting astride the wall, he helped to pull up his men, using his revolver at intervals and with such effect that he succeeded in shooting down the commanding mandarin. Young Chaplin, forcing his desperate way up the breach made by the artillery fire, was wounded a second time, and again was urged to attend to himself and abandon the colour. But he was not to be persuaded; he had got so far in the race, and was still ahead of the French officer; if he paused the Frenchman would cut in and plant his flag first on the fort. So the plucky young Englishman, only staggering a little from the shock he had received, struggled on again towards the “cavalier,” or highest point of the work. Only one Englishman, Lane, a private of his own corps, was in a position to render him any assistance; and the Chinese, frantic in their last dying efforts, were flinging away the ladders, and fighting against the besiegers with the strength of despair.

Young Chaplin was no less desperate, for he could hear the shouting of the French men almost by his side, but he would not be beaten. Struggling on, with sword in one hand and colour-staff in the other, and backed in his efforts by Private Lane, he made one tremendous effort, and clearing the way before him, mounted the cavalier, and shouting aloud the cry of “Victory,” was waving his flag aloft, when he was shot down, severely wounded in the leg. But he held his ground, though bleeding profusely (for he had been wounded three times), until his comrades gathered round him and he was saved. For this daring deed he received the Victoria Cross, and never was it more worthily bestowed.

4.5