Editor’s note: The following comprises the sixth chapter of Seven Roman Statesmen of the Later Republic, by Sir Charles Oman (published 1902).

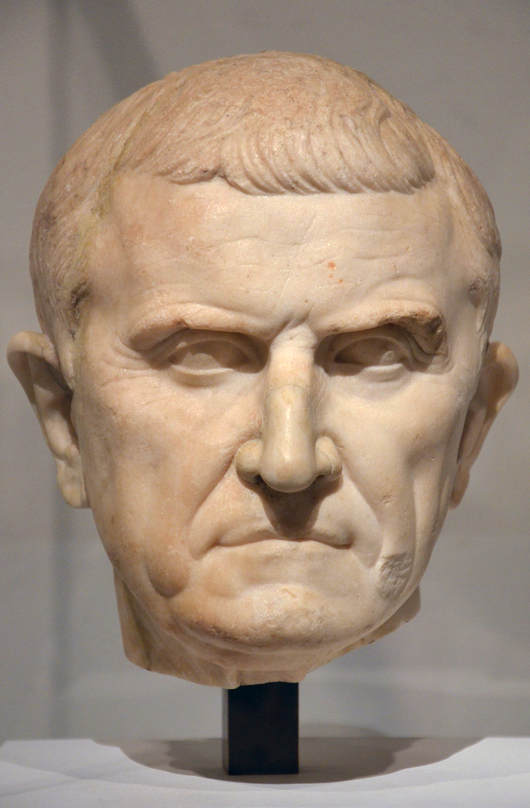

VI. Crassus

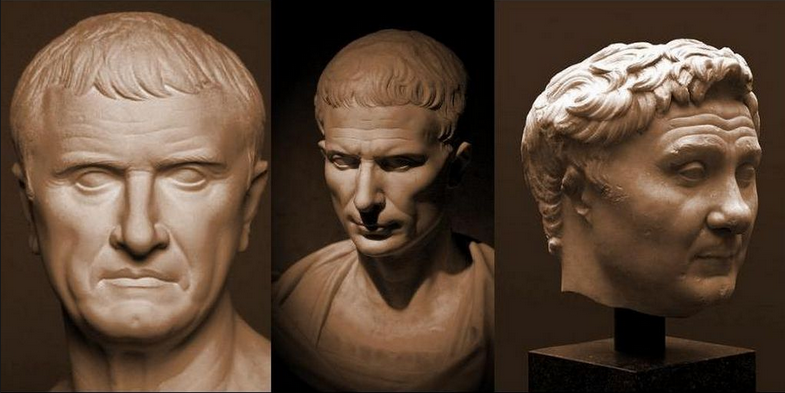

Napoleon, in one of his cynical moods, once asked his courtiers how the world would take the news of his sudden death, supposing that some chance bullet cut him off before his time. They hastened to give him all sorts of flattering versions of the dismay and regret that would fill all Europe. “No,” said the Emperor, “that is not the sort of thing that would happen. All that would occur would be that everyone would draw a long breath, and say with a sigh of relief, ‘Well, that’s all over.’ ” And so, it may be surmised, did things go at Sulla’s death. When men knew that his iron hand would never interfere again in politics, they felt as if a long nightmare was over, and abandoning the assumed characters that they had enacted during his lifetime, dropped back into their real selves. Instead of the majestic and united Optimate party which seemed to stand so firm under his protection, there was now only a mass of slack senators, who wished to take life quietly, with the maximum of enjoyment, and a few ambitious men who felt at last that they could display their ambition without risking their necks. The Senate still contained some men of real ability who were loyal to the oligarchic constitution, such as the Epicurean general Lucullus, Quintus Metellus, who had made a good military reputation, the orator Hortensius, and Catulus, the son of that Catulus who had fought so well against the Cimbri — a somewhat duller reflection of his father’s virtues. But the great majority were apathetic nobodies, while the two persons who were most important and influential among Sulla’s lieutenants were men who disliked the Sullan constitution, simply because it gave them no scope for the display of the considerable abilities which they possessed, and for the satisfaction of their ambition. It is mainly on the doings of these two, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gn. Pompeius, that the politics of the next twenty years were to turn. No two men could have been more unlike in character, but fate was always hurling them together, first as young soldiers in Sulla’s camp with fathers to avenge, then later as consuls in the same year, lastly as members of the famous “First Triumvirate.” Of the idiosyncrasies of each of them we must endeavour to gain a firm grasp.

At first, however, there were circumstances which kept the ambition and the rivalry of Crassus and Pompey from assuming the importance which they afterwards attained. In 78 B.C. men’s attention was mainly occupied by certain evils, which, as long as Sulla lived, had given the government little concern, because they knew that, if things grew serious, one nod of Sulla’s head would suffice to set them right. When he was removed, these problems suddenly began to cause alarm. First, there was suppressed unrest in Italy; the children of the Proscribed, deprived of all political rights; the citizens of the Etruscan towns, who had escaped massacre but had not escaped confiscation; the numerous population in the valley of the Po, who had obtained Latin rights from Pompeius Strabo, but wanted to become full citizens — were all discontented. The wrecks of the bands of Carbo and the younger Marius were not entirely dispersed: some were pirates on the high seas, others freebooters in Mauretania. In Spain their strongest man, the ex-praetor Sertorius, had raised a really dangerous insurrection — a peril to the state, not so much because it was a lingering remnant of the civil war between Roman and Roman, as because Sertorius was gradually de-Romanising himself, and becoming a Spanish national leader rather than a representative of the old party of the populares. Of him we shall have more to say when we deal with the life of Pompey. As long as Sulla lived, the Optimates talked of him as a tiresome survivor of a long-lost cause, much as we talk of Botha or De Wet. After the dictator’s death it became clear that his insurrection, far from dying down, was distinctly spreading over a wider area, and threatening to tear away the whole of Spain from the Roman Empire. It had already been the death of several incapable Optimate generals, and the ruin of several small armies. The outlook in the West was gloomy.

But in the year that followed Sulla’s decease it was not Sertorius who seemed the most dangerous foe of the senatorial government. Their main trouble was caused at home, by the vain and heady consul, M. Aemilius Lepidus, who tried in the most reckless fashion to pull down the whole of the new constitution almost before its founder’s ashes were cold. Lepidus was “a rash, intruding fool,” whose motive was nothing more than the ill-regulated ambition of a man who does not know his own mediocrity, and thirsts to be something great. He draped himself in the torn and soiled mantle of Saturninus and Cinna, and appeared in the character of a Democratic saviour of society. Now, the large majority of the people of Rome and of Italy disliked the senatorial regime, but disliked still more the idea of the recommencement of the civil war and all its horrors. The consul found little support, but contrived to gather in Etruria an army of political refugees, discontented politicians, liberated slaves, and even bankrupt Sullan veterans. The whole of this rising bears an astonishing resemblance to the doings of Cataline in the same district fifteen years later. It failed in much the same way.

When Lepidus led his horde against the city, the Senate hastily fitted out an army against him under Catulus. These raw levies were just ready when the ex-consul reached the Tiber, and actually crossed it at the Mulvian Bridge and entered the Campus Martius. Here, among the monuments and polling booths, Catulus and his legions met him and gave him a severe defeat. He retreated into Etruria, took ship to escape his pursuers, and died immediately after in Sardinia, whither he had fled. The strongest body of his followers that held together was defeated by Pompey in Cisalpine Gaul, and its leader, M. Brutus, was captured and executed at Mutina. Only a small part of Lepidus’s insurrectionary host, headed by the Praetor Perpenna, escaped by sea, and went to join Sertorius in Spain. There the insurgents were making marked progress; they carried all before them, and were not even checked when Pompey in the next year led a considerable army of reinforcements from Italy against them.

While the revolt of Sertorius was taxing all the energies of Rome, there were two other important struggles in progress. The first was the renewed war with Mithradates, an ill-managed and interminable struggle, in which the king of Pontus, whom Sulla had beaten with such ease and rapidity, baffled all the Roman generals for ten years, so that even the very capable L. Lucullus, the best general of really loyal mind whom the Senate possessed, could not entirely subdue him, though he beat him in battle often enough.

The third, and the most difficult and disgraceful of the three military problems with which the oligarchy had to deal in these troublous years, was the great slave-rising in Italy under the Thracian Spartacus, who beat ten Roman armies, and equipped forty thousand men from their spoils, though he had started as the leader of no more than seventy-eight runaway gladiators. Scandalous as it appeared, the Senate could not prevent the untrained hordes of Spartacus from ranging over the whole of Italy, from the Po to the straits of Rhegium. For several years he marched and countermarched among the Apennines like a second Hannibal, and won battles over the incapable Optimate generals that were in their way hardly less notable than Trebia or Trasimene.

The government whose weakness provoked, and whose incapacity protracted, the three disastrous wars with Sertorius, Mithradates, and Spartacus, deserved to fall. It only needed someone more able than the vain Lepidus to lead the attack on the Sullan state-system, and it was bound to crumble down. But the blow was to be given not by one man but by two. Pompey was returning from Spain on the one side, on the other Crassus was about to come to the front. Of him we have now to speak in detail; hitherto we have barely mentioned his name.

M. Licinus Crassus had been born in or about the year B.C. 107. We have already had occasion to tell how his father, Crassus the ex-consul, and his elder brother, Publius, fell in the great massacre of B.C. 87, hunted down by the gangs of Marius. But Marcus, the younger son, escaped through untold perils to Spain, where he lay hid for many months in a cave by the sea-shore. When he emerged from his lurking-place, it was to become a freebooter on the high seas. At last he heard that Sulla had returned to Italy, and sailed to join him at the head of his band of outlaws. He applied to the proconsul for a military command and a detachment of troops. “I can only,” said Sulla, “give you as helpers the ghosts of your murdered father and brother.” Crassus quite understood his chief’s meaning; the Optimate army was so small that there was not a man to spare: the spur of revenge must serve him instead of regular resources. With no more than his original band of outlaws, he made a dash into the Marsian territory, and there succeeded in raising a considerable body of troops. When Sulla advanced into Central Italy, Crassus guarded his flank; after Rome fell, he was sent up into Etruria, where he did good service against Carbo and his crew. But his most striking exploit was that he saved the fortune of the day at the battle of the Colline gate; his wing, it will be remembered, was successful, while that of Sulla was broken and pushed back to the walls. It was only delivered in the end by the help of Crassus, who used his own victorious legions to save his leader from destruction.

At the end of the civil war, then, Crassus had achieved a brilliant military reputation. Of all the Optimate generals, there were none who were more esteemed, save Pompey and the ambitious and ill-fated Lucretius Ofella. The latter was soon cut off, but with the former Crassus had already started that rivalry which was to endure throughout both their lives. As the elder man, he bitterly resented the fact that Sulla always gave the higher place to Pompey, and honoured him with a distinction and a confidence that he accorded to no other of his subordinates.

Nevertheless Crassus might have gone far, and have been reckoned among the leading lights of his party, if he had not managed to offend the dictator, and to get himself marked down as a man who was not to be trusted. Hitherto his career reads like that of an adventurous soldier, but in his last campaign he was beginning to show the traits which were to be so prominent in his later life — that unscrupulous greed for money and that indifference as to the means by which it was to be got, which were to be alike his strength and his weakness during the rest of his life. Sulla’s anger with Crassus arose from two sinister incidents. At the siege of Tuder in Umbria, Crassus had captured the military chest of the Democratic consuls; instead of handing over its contents to the treasury, he embezzled the whole for his private profit. Later in the war, being in command in Lucania and Bruttium, he committed the unpardonable offence of slaying some local magnates, whose names had never appeared in the proscription list, and seized their wealth for himself. Now Sulla, though he was ruthless in blood-shedding, had a system in all that he did, and objected to seeing his plans for weakening the Democratic party turned to the use of private greed. He was deeply incensed at Crassus for slaying men uncondemned by himself, and when his command ran out, sent him into private life with a bad mark against his name. He did not prosecute him, or drive him out of the Senate, but simply noted him down as a man not to be trusted or employed.

Having lost his military career, and being barred out of political advancement, Crassus turned his energies into money-making, and laid the foundation of the vast fortune which he was to accumulate by lucky speculations in the property of the proscribed. The Italian money-market was glutted with lands, houses, and investments belonging to the fallen Democrats. The man who had a little spare money to invest could, at this moment, buy up great masses of property, which would recover their value in a few years, when the glut and the panic was over, and Italy had settled down into quiet. Crassus had not very great paternal wealth; his own moderate fortune reached the competent but not startling total of three hundred talents — some £75,000 of our money — but he had amassed great sums by plunder during the war, and he boldly sunk every sesterce that he could scrape together in buying up depreciated lands and houses in and about Rome. He had his reward within a short time. When public confidence had been restored, and prices had risen to their old level, he found himself a millionaire. What his wealth was at this period we cannot say, but at a later time it amounted — after a year of exceptional expense in all sorts of political corruption — to no less than seven thousand one hundred talents — one million seven hundred and seventy thousand pounds of our money.

While Sulla still lived, and while the oligarchy still hung together after his death, Crassus, excluded from public life, went on conquering and to conquer in the world of finance. Plutarch gives us most extraordinary details as to his ingenious and often undignified methods of money-making. Not only did he lend money at high rates of interest both to Roman senators and to provincial municipalities, but he invented strange devices of his own. One of them was his school for the education of slaves. He used to buy the raw material, and have them trained as readers, book-keepers, stewards, and cooks. It is said that he not only supervised the school, but often gave lectures himself — in the cooking of accounts, rather than of entrées, it is to be presumed. The slaves who had been through this academy sold at much enhanced prices.

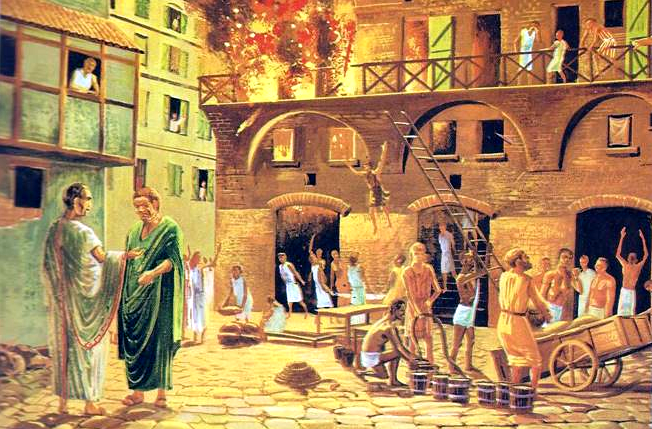

Still more astonishing was his amateur fire-brigade and the way in which he used it. He got together a body of five hundred workmen — carpenters, masons, and the like — provided them with ropes, buckets, ladders, and tools. Whenever there was a fire (and fires were as common as they were dangerous in the crowded city), he went down at the head of his gang and called on householders whose property was in the immediate neighbourhood of the conflagration. He then offered to buy their houses, as they stood, at a very low figure. If the terrified owner consented, the fire-brigade was turned on and the mansion generally preserved. If he refused, Crassus went away with his men and let the fire do its worst. Hence in time, says Plutarch, he became master of a very appreciable part of the house property of Rome. Historians have often written of this bold speculator as if money-making was his main purpose in life, and politics no more than a diversion to him. But he was no mere money-bag, no gatherer of wealth for its own sake, without any further end. Crassus was even more ambitious than greedy, and his huge accumulations of money were made for the definite end of raising himself to a high place in the state. They err who represent him merely as an ingenious and shameless financier. Crassus had felt bitterly the ostracism from public affairs to which Sulla had condemned him, and he was determined to win his way back to a prominent part in politics. Since the oligarchy had banished him from their ranks as a corrupt and untrustworthy member, he would get back to power by taking up the cause against which he had fought so strenuously in his youth.

Crassus had in reality nothing of the Democrat in him. The only point on which he touched the sympathies of the Democratic party was that by his enormous money-making, and the place to which he had risen in the world of finance, he had made himself the king and lord of the whole tribe of publicani, who, as members of the Equestrian Order, had been so badly maltreated by Sulla, and who were there fore constrained to fall back on their old alliance with the populares. Except in the fact that his interests were bound up with this class, he had no further connection in feeling or sympathy with the Democrats.

The basis of the influence which Crassus wielded was no doubt his importance as the leader of the Equestrian Order and the publicani, won by the fact that he was concerned in all their financial ventures. But it was not only in commercial circles that he had extended his influence; it was his object to make himself a power, by having as many persons as possible of all classes interested in his success and bound to him by obligations of one sort and another. Two of his methods are especially dwelt on by Plutarch; the first was his willingness to act as patron to any one who applied to him, and his constant appearance in the law-courts to defend all manner of clients. He was not a first-rate speaker, tending to be dull and prolix, but he always “got up his brief,” and often beat better men, because he came prepared with facts, while they relied merely on eloquent declamation or personal abuse. Often when Hortensius or Cicero had refused to take up a case, he would undertake it, for he considered few persons too unimportant to be worth serving. An obliging, even an unctuous, manner and a real capacity for taking pains in small things gained him many dependants. “He never neglected to return a salutation, and could address an almost incredible number of citizens by their proper names.” In this respect he was just the opposite of his opponent Pompey, who was gauche and ungracious.

His other method of winning influence was the more practical one of getting into his net any man who seemed likely to be useful, by offering to lend him money. Pushing young men who took to politics he was most eager to oblige, not charging too heavy interest, nor sometimes any interest at all. He lost enormous sums of money in this way, for, of course, he was frequently repaid neither the capital nor the interest; but he got instead what he cared for even more than money, a personal influence over all kinds of people in the most various walks of life, so that he could pull the wires in all manner of political circles without his hand appearing; for, of course, his debtors would do anything to keep him quiet. It is this personal consideration which explains the indulgence which the Senate showed him; there were so many individuals in it who owed him money that their collective influence prevented him from suffering at the hands of the whole oligarchic party. Still these supporters were purely interested and venal, and not to be relied upon; like Richard III, as described by More, “With large gifts he gat him unsteadfast friendship.”

The reappearance of Crassus in politics came about owing to the disasters which the Senate suffered in the war with Spartacus. Several considerable armies, commanded by oligarchic nonentities, had been destroyed by the brigand and his horde, who ranged all over Southern Italy at their will. Resolved at last to look for a competent soldier of approved capacity, the Senate were almost forced to use Crassus, who (as we have already seen) had gained a reputation in the civil wars second only to that of Pompey. The other two possible men were unavailable: Pompey was in Spain fighting Sertorius, Lucullus in the East fighting Mithradates. When appointed general, Crassus set to work at once to discipline the beaten and demoralised legions which were handed over to him by his predecessor in command. He tried all methods with them, both those of persuasion and those of punishment. On one occasion he is said to have used, to a legion which had disbanded in the face of the enemy, the terrible old punishment of decimation (if we may use the word, for he took by lot one man in every fifty, not in every ten, and put him to death). Whether by fear, or by the good and regular pay and provisions which he secured for his men, Crassus got them into a better fighting mood than they had shown of late, and gave Spartacus the first check that he had received. At last he blocked him up by a circumvallation near Rhegium in the tip of the Bruttian peninsula. The rebel burst out, losing many men in the attempt, but was chased north by Crassus, who at last caught him and his main body in the open field, and slew them all in a battle in Lucania. Only scattered bands got away to the north.

The war was practically settled when Pompey suddenly appeared upon the scene. The young general, who was to be Crassus’s rival and yet his ally, had just put an end to the Spanish war, favoured, as we shall see, by the lucky chance that Sertorius had been murdered by his own jealous lieutenants. Returning with his army, he caught the last bands of the defeated rebels as they tried to escape across Northern Italy and cut them up. For this Pompey took over-great credit, remarking that Crassus had beaten Spartacus indeed, but that he himself had “torn up the war by the roots.”

Two generals with two victorious armies were now approaching Rome from the north and the south respectively. Both were able and ambitious, and both detested the constitution of Sulla and the senatorial oligarchy, which stood in the way of their holding continued power. But they also hated each other as much as they hated the Senate, and were inspired with the bitterest jealousy. The all-important question was whether they would fight, or whether they would prefer to join their forces against the Optimates. It was the latter alternative that they chose. Pompey was too irresolute and conscientious, in his own way, to strike hard to win a tyranny. Crassus had the smaller army, and dreaded the military abilities of his rival. Hence it came to pass that they agreed to join in a campaign against the Senate and the Sullan constitution. They stood for the consulship for B.C. 70, keeping their legions outside the gates as a threat to people and Senate. The populace, indeed, did not need the threat, and was ready to do anything which would annoy the Fathers. So Pompey and Crassus were duly elected consuls, under the eyes, as it were, of their respective armies. It was a mere compromise, which satisfied neither of them, for each thought the other’s presence very unnecessary. But since they were not prepared to fight, and neither of them had a real conception of a policy, nor a definite idea of what he himself really wanted, Pompey nor Crassus could not ask or receive any more.

So these two ambitious men, masquerading as Democrats, undid the constitution of Sulla at their leisure, meeting no opposition from the demoralised Senate. Without a man of genius to lead them, or an army to oppose to the two great hosts of Pompey and Crassus, the Optimates could do absolutely nothing. Their one great fighting man, Lucullus, was still in the East, and could not be called from thence to play the part of Sulla, firstly, because he had no wish to do so, being as careless as he was able, and secondly, because he could not have trusted his army to follow him. In spite of all his victories he was most unpopular with his soldiery.

When Pompey and Crassus had been installed in office, they proceeded to introduce a series of laws which destroyed all the main features of the Sullan constitution. But, as we shall see, they put nothing in the place of that which they were destroying, and the only result of their so-called reforms was to restore the constitutional chaos and the conflict of sovereignties which had prevailed in Rome from the rise of the Gracchi down to Sulla’s legislation of B.C. 81. The fact is that they were bent, not on supplying Rome with a workable state system, nor even on harking back to the old Democratic projects of Saturninus and Cinna, but merely on smashing up those sections of the Cornelian Laws which stood in the way of their own ambitions. If they added some other measures to their legislative output, it was partly to achieve a little cheap popularity, partly to make a show of having a real constructive programme of their own — a thing which was, in fact, non-existent.

As a first measure, the various securities which Sulla had provided to protect the Senate against disturbance were now done away with. Once more, as in old times, the tribunes were to be permitted to propose laws to the public assembly without having first obtained the Senate’s leave. The other disability which had been imposed on them by Sulla, that of never being allowed to stand for any other office if once they had chosen to take the tribunate, seems already to have been removed by a law passed in B.C. 75 by Gaius Cotta. But this relief was a mere nothing to the boon now granted by Pompey and Crassus. The right to deal with the people without any senatus auctoritas was the real strength of the tribunate in all ages.

Secondly, and in this point Crassus was particularly interested, the Equestrian Order, of which he was the patron and lord, was restored to its old position in the state. The knights were given back the privilege of farming the taxes of Asia, which Sulla had taken from them. Moreover, the Lex Aurelia restored to them once more a predominant share in the law-courts. They did not obtain, as in the days of Caius Gracchus, a monopoly of judicial power, for in future juries were to be made up of three classes of citizens. One-third were to be senators, one-third equites, one-third tribuni aerarii. But the knights seem to have secured something like their old control, because the third order, the tribuni aerarii were, from their fortune and tendencies, much more akin to them than to the senators: indeed, they were in a sense members of the Equester Ordo. This elaborate subdivision of classes in the courts does not seem, if we may trust Cicero and other witnesses, to have made any sensible improvement in the justice which Roman juries dispensed.

It was almost inevitable that Pompey and Crassus, seeking to ingratiate themselves with the Roman multitude, should hark back to the most popular and the most pernicious item of the old Democratic programme, by developing again the corn-dole, whose abolition had been by far the best of Sulla’s measures. But to buy support from any class by lavish expenditure, whether from his own or from the public purse, was a regular part of Crassus’s system. A moderate and limited amount of distribution had been restored as early as B.C. 78. But the consuls of B.C. 70 presented every citizen with corn for three months without exacting any payment. Crassus is also said to have given an enormous public dinner to the populace at the feast of Hercules, at which all comers were entertained at ten thousand tables laid down the streets.

Another political move of the consuls was the restoration of the Censorship, which had been practically in abeyance since Sulla’s time. The first new censors, Cornelius Clodianus and Gellius Poplicola, celebrated their advent by a wholesale eviction of Sullan partisans from the Senate, which they could do all the more plausibly because many of the sufferers were men of blemished reputation. It will be remembered that the ex-consul Lentulus, the associate of Catiline, was one of the victims of this purging; he was expelled for what the censors called “luxury,” i.e. notorious evil living.

It is most noteworthy that Pompey and Crassus did not include in their legislation two measures which any genuine Democrat would have been certain to insert in his programme. The first was the cancelling of the effect of the Sullan Proscription; it would have been natural to secure the return of the exiles, and to restore their status as citizens to the “Sons of the Proscribed,” whom the dictator had deprived of so many rights. The second obvious measure would have been the institution of an inquiry into the awful deeds of murder and robbery which had been perpetrated, without any shadow of legality, during and previous to the dictatorship. The reason why these subjects were left untouched was that Crassus himself had been deeply implicated in the worst part of the Proscription. He had put men to death illegally, had seized on lands without any good title, and had bought up whole sale the property of the proscribed. Pompey, too, had some acts to his account which would not have looked well when investigated in a court of law, such as the executions of Carbo and M. Brutus. They had, no doubt, been declared outlaws by the Senate, but the officer who had put them to death would have felt some qualms in the days of a real Democratic reaction.

It was therefore impossible for the consuls of B.C. 70 to raise either of these questions, as it would have entailed inquiry into their own conduct, and in the case of Crassus the surrender of masses of ill-gotten property. It was not till a real Democratic programme was being brought forward, somewhat later, by Julius Caesar, that the idea of the punishment of the people’s enemies was mooted, by the celebrated trial of Rabirius for the murder of Saturninus. As to the rank and file of Sulla’s assassins, the only person who ever took arms against them was one of their own party, the stern and rigid Cato, who, when he was quaestor, insisted on recovering from them the blood-money which the dictator had issued to them without legal warrant.

Though allied to overthrow the supremacy of the Senate, Pompey and Crassus did not learn to love each other any the better during their year of joint office. Their quarrels were unending; ” they differed about every measure that came before them, and these disputes and altercations prevented each of them from doing many things on which he was set.” It was this notorious enmity which led to a curious scene at the end of their year. When it came to be time for them to make their final orations to the people on quitting office, there stood forward a certain knight named C. Aurelius, a person of no note, who said that Jupiter had appeared to him in a vision, and commanded him to tell the Romans that it would not be lucky for them if they allowed their consuls to remain unreconciled. Wherefore he suggested that they should embrace in public. At this unpalatable proposal, the two magistrates were much disturbed: each stood lowering at his own corner of the rostra. But when the people continued shouting for a long space of time that the consuls must be reconciled, Crassus at last constrained himself — he was far the better hypocrite of the two — went up to Pompey and offered him his hand with a well-turned compliment. They embraced, parted, and hated each other rather more than before. The humorous Aurelius must have extracted huge enjoyment from the little comedy.

The two years that followed the resignation of the consuls on December 31, B.C. 70, are most difficult to understand. We should have expected that the enmity of Pompey and Crassus would have led them into some open outbreak against each other, the moment that they had ceased to be colleagues. But nothing of the kind happened; it seemed as if each had destroyed his rival’s power of initiative. They remained watching each other and did nothing more. The Senate, which had thought that its last day had been at hand, was able to breathe again and to seek feebly to reassert itself. It had been generally expected that Pompey would choose some important province, and would provide himself with another army to replace that which he had disbanded after his Spanish triumph; but this was far from his thoughts; before his consulate expired he expressly disclaimed any such idea, and for the whole of 69-68 he remained quietly in Rome living the life of a private citizen. Probably the sight of his rival in retirement soothed down the anger of Crassus, who had half expected him to aim at a tyranny. For he too kept quiet, and relapsed into his normal round of money-making and wire-pulling on the back-stairs side of politics.

So things remained, the two great men keeping each other under close observation, but making no offensive move, till Pompey was at last called away by the Gabinian Law (B.C. 67), which gave him the command against the Pirates. In consequence of this commission, and of the subsequent Manilian Law, which transferred to him the command against Mithradates, he was absent from Rome for nearly seven years. Crassus had at first intrigued against the assignation of such important charges to his rival, yet, when he was gone, was glad to see the political stage left clear for his own action. While Pompey was away, he would have a better chance of convincing the Roman people that he was their true friend, and of carrying out his plans for his own personal aggrandisement. But, as we shall see, all the political intrigues of Crassus failed: while Pompey in the distant East was adding laurels to laurels in a way that kept his name perpetually before the citizens, and made it probable that when he should return, with his army at his back, he might ask for anything that he chose, with a perfect certainty of receiving it.

We seem to trace in the doings of Crassus during Pompey’s absence in the East a progressive series of measures, by which he hoped to commend himself to the Democratic party, and to establish himself as their leader so firmly that his position should be unassailable on his rival’s return. He had now bought himself a most able managing partner in the person of Julius Caesar, whose first prominent appearance in politics belongs to these years. The young man possessed the two gifts of eloquence and geniality, in which both Crassus and Pompey were so hopelessly lacking. But at this period of his career he was impecunious and a trifle disreputable; no one foresaw in him the future dictator and the founder of the monarchy. At this time he was absorbing Crassus’s money at a preposterous rate, and flinging it about with both hands. Men looked upon him much as they looked upon Clodius ten years later, and never suspected that the lieutenant of Crassus was more than a splendid mob-orator and a skilled manager of “corner boys.”

The chief landmarks of this period of Crassus’s political career are a series of bids for popularity, which failed to produce the desired effect. As censor in B.C. 65 he tried to enrol as full citizens the entire population of Cisalpine Gaul, but his colleague Catulus refused to recognise the grant, and the Optimates continued to deny it right down to the Civil War. Another and more ambitious scheme was the bill to annex Egypt in the same year, the chief object of which seems to have been to find an excuse for giving Caesar an army which might serve as a counterpoise to that of Pompey. But the Senate succeeded in stopping the design. A little later it would seem that the Democrats were growing more desperate. Caesar’s attack on Rabirius was a warning to the Optimates that extreme measures might be tried against them, if they stood in the way of his employer’s road to power. But the bill of Servilius Rullus was far more startling: it styled itself an Agrarian Law, but was much more like a measure for suspending the constitution. With the ostensible object of relieving economic distress at Rome, it proposed to create a body of Decemvirs, with far greater powers than the Triumviri agris dandis assignandis of Tiberius Gracchus had ever held. These Land Commissioners, of whom Crassus and Caesar were to be the chiefs, were to be granted the military imperium and the right to levy troops. They were to be permitted to select 200 subaltern officers from among the Equites, to have power to sell the public lands in Italy, and in the provinces, to plant colonies, to take out of the treasury whatever they wished, and to sit in judgment in all lawsuits which might arise from their own proceedings. Considering that the law was mainly levelled against Pompey (for it was of him rather than of the Senate that Crassus was in fear), it was adding insult to injury to place the public lands and revenues of Syria and the other newly annexed Eastern provinces at the disposition of the Land Commissioners. The immense machinery provided by Rullus was so disproportionate to the task which it had to serve, and the power given to the Decemvirs so inordinate (their very name recalled the old tyrannical ten of B.C. 451-450 and the misdoings of Appius Claudius), that the bill failed to pass. Cicero headed against it a combination of the Optimates and the friends of Pompey, who when allied proved able to triumph over the Democrats, in spite of all the bribes of Crassus and all the eloquence of Caesar.

But the agrarian law of Rullus was not the strangest project that was attributed to the two Democratic leaders. There were many who accused them of being implicated also in the reckless plots of L. Sergius Catilina.

It is impossible to arrive at any certain conclusion concerning the character and scope of the so-called Catilinarian conspiracies. If we were to accept in its entirety the official narrative, which was composed by Cicero, and practically embodied wholesale in Sallust and most other historians, we should regard the participation of Crassus in the designs of Catiline as most improbable. We are told that the leader of the plot was a monster of depravity, a sort of malignant demon in human form, who, after spending his early years in murdering his relatives and debauching all the youth of Rome, wished in his middle age to inaugurate a reign of coedes and incendium, to massacre the Senate, burn the city, and rule as a tyrant among the corpses and the smoking ruins. If there were any truth in all this, we should conclude that Crassus, as the largest householder in Rome, was not likely to be privy to a plan for whole sale incendiarism, and, as the greatest creditor in the city, would hardly wish to massacre a Senate in which a vast number of the members owed him large sums of money.

But Cicero himself furnishes us with much evidence for doubting his own narrative. If Catiline was such a notorious villain, it is odd that the orator should have proposed to run with him as a joint candidate for the consulship, and have offered to defend him when he was going to be indicted for extortion in his late province of Africa. Still stranger are Cicero’s statements in the Pro Coelio, where (defending a friend of the conspirator) he remarks that he was always meeting Catiline in the best society: “I thought him a good citizen, and esteemed him for the many eminent virtues which he seemed to possess.” If it was possible for Cicero to make such allegations with any show of good faith, it is clear that Catiline cannot have been the social pariah who is described in the orator’s speeches of B.C. 63. Evidently the fluent consul, thinking his own neck in danger, had painted his foe and all concerned with him in very lurid colours.

It is impossible, on the other hand, to believe (with Professor Beesly) that Catiline was a respectable politician and the avowed head of the Democratic party at Rome during the years B.C. 65-63. If he had been beyond reproach, Sallust and other historians of the Caesarian faction would have taken the opportunity to represent him as a martyr to the jealousy of the Optimates and a victim of Cicero’s spiteful tongue. Since they did not dare to take this line, and reproduced the orator’s account of him almost verbatim, we are driven to conclude that the insurgent chief was really a man of doubtful character and reckless designs. But at the same time we are forced to believe, from Cicero’s own evidence already quoted, that he had not such a notoriously bad reputation as to make it impossible to use him as an associate or a tool in political schemes. If we look upon him as no more than an unscrupulous demagogue of the same type as Saturninus or Clodius — that is, as a desperate brawler and mob-leader rather than an anarchist — it does not seem so unlikely that Crassus and Caesar may have had relations with him during the years of his activity. If their plan was to have a bold and reckless Democratic consul — a man who would not shrink from using violence when the crisis came — in power, when Pompey should return from the East, we can well understand that they may have taken Catiline into their pay. He and they, in short, may well have been aiming at a coup d’état, though it is most improbable that they intended either to massacre the whole Senate or to set the city on fire. These accusations are the embroidery with which Cicero adorned his orations, when he wished to enlist all the men of material interests on the side of the Optimates. Not only did he succeed at the moment, for even the Equites were seen with swords in their hands offering to kill Caesar, but he has left for all ages a stain on the name of Catiline which is probably one or two shades deeper than that very unscrupulous politician really deserved.

The story of the Catilinarian plots, as we now have it, is too fragmentary and too obscure to bear complete unravelling. The version of the first plot, in which Caesar and Catiline are said to have assembled a mob of assassins in order to murder the consuls of B.C. 65, Torquatus and Cotta, and then to have failed to give the signal for the onset, is most unconvincing. Concerning the conspiracy of B.C. 63 we have more details, but they are very contradictory. On the one hand, we know that there was a widespread rumour that Catiline was acting under the orders of Crassus. Sallust, no unfriendly witness, allows that a great part of the Senate suspected the great millionaire of being implicated in the plot. On the other hand, it is certain that Crassus volunteered some information to Cicero concerning the designs of the insurgents, though that information was tardy and practically useless. He is said to have come in a melodramatic manner, late at night and muffled in a cloak, and to have placed in the hands of Cicero an anonymous letter which had been delivered to him, warning him to be out of Rome on the day of the preconcerted outbreak. If this midnight visit really occurred, it is probable that Crassus was merely “hedging,” — that he told Cicero what he considered would be enough to protect him from a charge of complicity if the plot should fail, but not enough to do Catiline and his colleagues any harm if they were going to succeed.

One thing is clear — that Cicero did not consider it prudent to assail Crassus, and remained deaf to all the suggestions made to him with that object. Another public man, when incited to fall upon the millionaire, once answered with the proverb, “Foenum habet in cornu” meaning that Crassus was too dangerous a sort of game for a hunter of his calibre to meddle with.[1] And so the consul of B.C. 63, with his usual prudence, refrained from accusing of high treason a man who could pull so many political strings, and had at his disposal such a command of money and influence. When the informer Tarquinius, in his examination before the Senate, began to give evidence incriminating Crassus, a curious scene occurred. Dozens of senators who owed Crassus money began to shout “false witness” with all the power of their lungs. Then Cicero, after glancing round the house and pondering on the situation, took the easiest way out of the position by remanding Tarquinius to prison, without permitting him to go on with his story. The charge was not allowed to be repeated, yet Sallust tells us that Crassus was so far from being grateful to Cicero that he ever afterwards regarded him as an enemy. Apparently he thought that the orator had been feeling the pulse of the Senate by producing such evidence, and had only drawn back from an open attack because he saw that he would not get the full support of his party if he persisted.

However much or however little Crassus had been implicated in the Catilinarian plot, this much is certain, that many people thought that he had known more about the business than he should, and that an additional stain was added in consequence to his already not unsmirched reputation. We are told that in the end of B.C. 63 he seriously thought of leaving Rome to preserve his personal safety, and provided ships to carry himself, his family, and his treasures out of Italy.

The reason why he did not actually depart was the unforeseen delay in the return of Pompey from the East. The conqueror of Mithradates had finished his military work in B.C. 63 by the conquest of Syria. He was expected back early in 62, just when Cicero’s consulship had expired, and while the embers of the Catilinarian conspiracy were still smouldering, after the main conflagration had been quenched. If he had presented himself at this moment, he would have found the Democratic leaders in the deepest discredit and dismay, and foiled in all their plans to raise up a power in Italy that should be able to oppose him. But Pompey chose to linger in the East for the whole summer of B.C. 62, pacifying and portioning out provinces, conciliating allied princes, and founding new cities. He showed no signs of coming home, and merely sent ahead his foolish and talkative partisan Metellus Nepos, the man whose pranks gave Cicero so much trouble. It will be remembered that his demands were so unreasonable, and at the same time so vague, that Cicero and the Optimates ventured to oppose them, and Crassus had time to recover from his panic and to reconsider his situation. There can be no doubt that the follies of Metellus, who certainly exceeded the commission that had been given him, did his employer much harm and lessened his popularity.

Yet when, in the autumn of B.C. 62, Pompey at last announced that he was returning to Italy with his army at his back, both Democrats and Optimates were seriously alarmed. Externally his position was so much like that of Sulla in 82 that both parties had a suspicion that he would be tempted to repeat Sulla’s role. Neither Crassus and Caesar on the one side, nor Catulus and Cato on the other, felt their heads quite safe upon their shoulders. For each party knew that they had been intriguing against the great general in his absence, and supposed that he might resent their action in a very drastic fashion.

Nothing of the kind happened. With rare civic virtue Pompey dismissed his army, and returned as a private person to Rome, expecting to receive from his fellow-citizens the praise and gratitude that he had so well earned. Instead, he found the Optimates captious and critical, and the Democrats far more concerned in the Catilinarian conspiracy and its results than in the newly accomplished conquest of the East. His simple and moderate requests — the confirmation of his administrative work in Asia and the provision of the rewards due to his victorious soldiery — were refused him. When he put forward his friend the Tribune Flavius to pass a plebiscitum for the grant of lands to the army of the East, it was defeated by the unexpected and immoral combination of the Optimates and the Populares.

The great object of Crassus at this time was to prevent at all costs the conclusion of an alliance between Pompey and the Senate, lest the combination of the two should reduce himself and his party to entire impotence. How he did it we learn from Cicero’s letters. When Pompey first returned to the city, it would have been quite natural that the orator and he should have agreed to work together; they had been old friends and allies in earlier days, their political views were not dissimilar, and if Cicero was now the most moderate of Optimates, Pompey was certainly the least democratic of Democrats. If the orator could have persuaded his friends to treat the great general with courtesy and ordinary consideration, and to grant his very reasonable demands, it is probable that matters would have settled down without any further trouble. But Cicero was still swelling over with pride at his successes in B.C. 63, and now thought himself quite as great a man as Pompey. His idea was to meet the proconsul with the phrase, “If you have saved the republic abroad, I have saved it at home.” In his vanity he imagined that the crushing of Catiline’s handful of desperadoes was quite as great an achievement as the conquest of the East. He was ready to assume an almost patronising attitude to his old chief.

The wily Crassus resolved to estrange the two by tempting Cicero into a display of foolish pride which should disgust Pompey. He carried out his shameless plan at the first appearance of the great general to take his seat in the Senate. The occasion ought to have been utilised to welcome and compliment Pompey according to his deserts. But when the proceedings had been commenced, Crassus rose and began a fulsome and interminable harangue in praise of Cicero’s consulship. Not only was the subject-matter stale, for Catiline had been put down a whole year before, but Crassus was the last man who should have launched out on such topics. He was known to resent bitterly all that the orator had done, and to be his secret enemy. However he began to declaim to the effect that “the preservation of his own life and liberty, his name and his fatherland, his wife and children, had all been the work of Cicero; that Rome had been saved from fire and sword was due to this great man alone,” and so forth. Cicero fell into the trap with the greatest simplicity. Instead of suspecting all compliments from this most doubtful source, he arose to continue the debate in his own self-laudation. The opportunity for conciliating Pompey, by turning the discussion on to his great deeds in the East, and paying him his due meed of praise, quite escaped him. Instead, he proceeded to sound his own trumpet in the most autolatrous fashion. Writing to Atticus in complete unconsciousness of his own folly, he says that “now was the time for my well-turned periods, my flowers of rhetoric, my antitheses and figures. You know my wonted thunders: this day they were so loud that I think that you must have heard them even where you are, in Epirus.” So having spoken at length of his own great doings, of the majesty of the Senate, the wickedness of the late conspiracy, and all his usual topics, he sat down, leaving Pompey unblessed. The general was not pleased: “intellexi hominem moveri” says Cicero, who had the best chance of knowing, for he was sitting next to him. He took the speech as a formal declaration that Cicero and his friends did not think much of his exertions in the East, and he was not far wrong.

Thus it came to pass that the shameless harangue of Crassus and the idiotic vanity of Cicero, which made him gorge the bait so greedily, began to destroy the chance that Pompey might enter into an alliance with the Optimate party, and become a defender of the constitution. His anger came to a head when at the instigation of his old enemy and rival, Lucullus, the Senate passed a decree that an elaborate inquiry should be made into all his doings in Asia before they were ratified. If anything was wanting to complete his discontent, it was the way in which his army was treated; the excuse made for denying its reward was that the treasury was empty — a manifest lie, for the enormous sums which had been paid in from his Asiatic spoils were still unexpended.

So the man who might, if he had been unscrupulous, have become tyrant of Rome, found himself flouted and set at nought, merely because he had behaved like a good citizen, and refrained from taking by violence that which was his due. He might have asked for anything that he liked while his army was still undisbanded. When he had dispersed it, Cicero’s stupid friends refused to listen to his pleas and left him shamed before the eyes of his veterans.

While he stood involved in this bitter disappointment, Pompey received the offer which changed the whole face of affairs. Crassus and Caesar and the whole Democratic party were still under a cloud, with a strong suspicion of complicity in the Catilinarian plot hanging about them. It would mean everything to them if Pompey, his respectability, and his veterans were placed on their side. Accordingly they offered him their assistance to secure the ratification of his Asiatic treaties and the grant of land for his legionaries, if he would join them against the Senate. It must have been a bitter moment for him when he was told that his desires might be gained, at the price of a second alliance with his old enemy Crassus, the man who had intrigued against him with such malevolent persistence all through the last ten years. But rather than break his word to his soldiers (whose interests he had promised to protect), and rather than endure more bullying from the Senate, he accepted the offer. The famous “First Triumvirate” was formed, Pompey contributing his great name, his respectability, and the potential aid of forty thousand veterans; Crassus, his inexhaustible money-bags and his power of intrigue; Caesar, his unrivalled talent for mob-management and his cool and level brain. At the moment most men thought him little more than the agent and tool of the two elder triumvirs; the revelation of his greatness was yet to come.

When the triumvirate had been formed, and (in spite of the opposition of Cato and a few more irreconcilables) had shown that it could sweep the streets and clear the Forum, it remained to be seen how the victorious three would use their power. The first thing that strikes the observer is that while Pompey got something out of his bargain, and Caesar a great deal, we can hardly trace any positive and tangible gain received by Crassus from his alliance with his old enemy. Pompey got his Asiatic doings confirmed; he was also enabled to give his veterans the land that he had promised them. Caesar obtained his consulship, passed all the laws that he chose to bring forward, and had the pleasure (which to a man with his sense of humour must have been considerable) of seeing his colleague Bibulus shut up in his mansion and “inspecting the heavens” day by day without any effect. Moreover, at the end of his year of office Caesar received the all-important provinces of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul, the district from which legions could best overawe Rome and all Italy.

But Crassus got neither consulship nor province, neither land nor ratified treaties. It is true that his position in politics was re-established; the slur that had been left upon him after the Catilinarian business was removed, and he could feel that he had pulled the strings of the whole intrigue. But of more definite profit we see nothing. The only satisfactory explanation of this curious fact is to remember that Crassus, all through his career, seems to have desired power as an end in itself rather than as a means to other objects. He was, to use a modern phrase, a man without a programme. He wanted to pull the wires of politics, rather than to carry out some definite policy when he had collected all the wires in his hand. If we must seek a modern parallel for him, we may think of that wonderful old Whig, the Duke of Newcastle, who allied himself with the elder Pitt on the terms that the latter should manage the whole imperial policy of Britain, while he himself should be permitted to conduct the parliamentary jobbery and intrigue. In short, when the opportunity came to him, Crassus had no particular set of measures that he wished to advocate. He was neither a true Democrat nor a true Oligarch. He had become the leader of the populares not because he had popular sympathies, but because he wanted at all costs to be the leader of some party. So the weakness of his position was, that having achieved his wish to obtain a share of supreme power, he had little that was definite to ask for. He merely wanted to be able to assert himself when he chose, to have his share in portioning out consulships and praetorships, to make money when and how he chose, and to use it by keeping dozens of minor political personages in dependence on him.

Hence it is that in the doings of the triumvirs during their day of power, it is hard to point out very much that can be ascribed to the personal initiative of Crassus. His main aim was to keep in check his ally Pompey, whom he hated no less than of old. That thereby he was helping a much more able man — Caesar — on the road to supreme power he certainly did not realise. We may make a shrewd guess also that it was Crassus who really set upon Cicero and drove him into exile, Clodius being merely his tool, and not the originator of the orator’s woes. We know from Sallust and Plutarch how bitter was the enmity that Crassus bore to the consul of B.C. 63, despite the flattery which he lavished on him when he was set on estranging him from Pompey. It is probable that the banishment of Cicero was his underhand revenge for seeing his old schemes frustrated; for both in the rejection of the law of Rullus and in the suppression of Catiline the orator had been the main cause of his defeat. On the other hand, it is hard to see that Clodius had really any adequate cause for the malignant persecution to which he subjected Cicero. The usual tale, that he had been angered by the way in which his ingenious alibi had been disproved, while he was being tried for the violation of the mysteries of the Bona Dea, does not seem to give a sufficient reason for his vindictive attacks on Cicero. If we imagine that he was spurred on by Crassus, the causes of whose enmity are so much more obvious, the matter becomes far more intelligible. If the triumvir simply delivered the blow at second-hand, it is quite in keeping with what we read concerning his feelings at this time. Plutarch tells us that he had conceived such a mortal hatred for the orator that he would have shown it by some act of personal violence, had he not been dissuaded by his son Publius, who chanced to be an old pupil and an admirer of Cicero.

Crassus was certainly closely connected with Clodius, whose acquittal at his trial for the violation of the Mysteries he had secured by his lavish bribery. He was the only one of the triumvirs who did not try to save Cicero from the worst extreme of exile, by pressing on him an honourable excuse for absence from Rome, in the shape of a legateship or a “free commission” to travel. That the orator himself suspected him of being at the bottom of his troubles may be judged from the fact that when writing from Thessalonica during his banishment, and estimating his chances of return, he speaks of Pompey as certain to be favourable — “Crassum tamen metuo.” He had a fear that Crassus might not prove so accommodating. However, having learnt the lesson that it was not wise to cross the triumvirs, Cicero was ultimately allowed to return, and soon after was formally reconciled to the millionaire by means of the young Publius, his faithful friend.

We have, on the whole, extraordinarily little recorded of the doings of Crassus between B.C. 59 and B.C. 56, a time when he ought to have been able to ask and obtain whatever he chose from his colleagues. He had his share, no doubt, in the management of affairs by the triumvirs in that rather chaotic time, when, to the outward eye, Clodius rather than anyone else seemed to be the real ruler of Rome. But apparently he was, as usual, more set on checking Pompey than on anything else. It is only in B.C. 56 that he again conies to the front.

By that time he had at last learnt, from the study of Caesar’s doings in Gaul, that any man who aspired to take his share in dominating Roman politics must have an army at his back. Hence it was that at the conference of Lucca he claimed not only the consulship for B.C. 55, but the command of the army of the East. He too must raise his legions, win his victories, and be in a position to meet Caesar and Pompey on equal terms, if troubles should ever again break out. Those superficial writers who think that he chose the rich Eastern provinces out of mere greed and avarice are clearly wrong. All through his life money-making was to him the means and not the end. What he really wanted to secure was a loyal army, not a few more millions to add to his hoards. That military glory had turned his brain, and that he desired to emulate Alexander the Great, and “to penetrate to the Bactrians, the Indians, and the Erythraean Sea, so that in his hopes he swallowed up the whole East,” we cannot readily believe. Clearly he wished to win a strong military position, such as could be secured by great conquests beyond the Euphrates, but it was needed mainly to help him to sway the balance between Caesar and Pompey in the domestic affairs of Rome.

Nevertheless, when he had once been granted his desire and placed in command of an army, his spirits seem to have risen; his mind harked back to his old campaigns of 82 and 71 B.C., and he appears to have cast from him the memories of twenty years of finance and intrigue, and to have tried to become once more the enterprising soldier that he had been in Sulla’s day. He showed a buoyancy of spirit that surprised every one, “indulging in vain boasts most inconsistent with his wonted demeanour, and most unsuitable to his age and his disposition — for in general he was far from being either self-assertive or conceited. But now he said that he would make the expedition of Lucullus against Tigranes and that of Pompey against Mithradates appear mere child’s play. Yet he now counted sixty years, and looked even older than he really was.”

The renewal of the triumvirate had so cowed the Optimate party that even Cato had to give up his attempt to struggle against the omnipotent three. It is, therefore, all the more curious to find that one man set himself to oppose Crassus’s designs, and that from mere personal enmity. This abnormal personage was the tribune C. Ateius Capito, one of those strange characters who move for an instant across the political stage, and are then lost in obscurity. He ventured to place a veto on the levying of legions for Crassus: it was quietly disregarded. Then he announced awful hindrances of portents and prodigies, which were also met with derision rather than attention; indeed, he was fined by the censor Appius for fabricating false omens. But he reserved his great coup for the day on which Crassus passed out of the gates to take command of his army. After one final and futile attempt to interpose his tribunicial veto, he took refuge in strange incantations. “He placed a censer at the gate,” we are told, “and threw incense upon it, uttering the most horrid imprecations and invoking strange and dreadful deities. The Romans say that these mysterious and ancient curses have such power that the man against whom they are directed never escapes ill-luck; nay, more, they add that the person who uses them is sure to bring misfortune on himself also.”

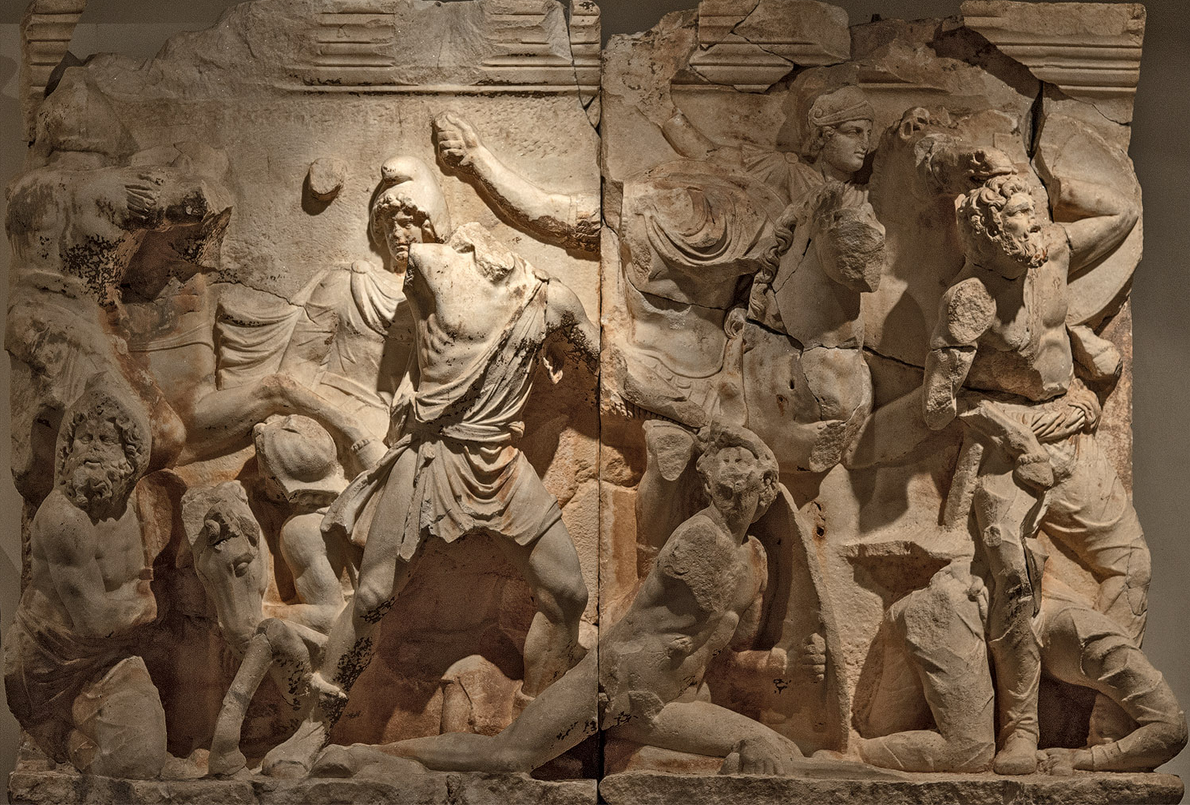

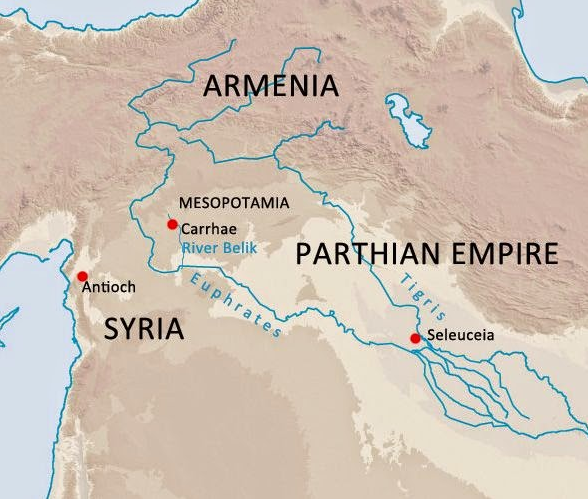

Undaunted by these antiquated rites, and regardless of two or three other evil presages which Plutarch has carefully collected, Crassus set forth from Italy and arrived safely in Syria, where he found himself at the head of an army of seven legions. His first act on taking charge of his province was to plunder ruthlessly the temples of Hierapolis, Emesa, and Jerusalem, and to scrape together all the money that could be raised by taxation. But he was no doubt set on filling his military chest for a war that was certain to prove long and costly, rather than on gratifying the talent for extortion that was such a marked characteristic of all his life. His first strategical move was to bridge the Euphrates, and to establish a new base for himself in the Greek cities of Mesopotamia. This was easily accomplished,but his second advance was a much more serious matter. He had now to prove whether his old martial reputation won in the wars against Carbo and Pontius and Spartacus had been fairly earned.

Quite unconsciously, Crassus was going forth to solve a new and difficult military problem. Unlike Caesar in Gaul, he had not to deal with an old enemy whose strength and tactics were well known. The Romans had met and defeated many an Asiatic army during the last century, but the Parthians were not like the other inhabitants of the Hellenized East, whom Scipio or Sulla or Pompey had so easily subdued. Their hosts did not consist of clumsy imitations of the Macedonian phalanx, but of masses of horse-bowmen. Some were the lightest of light cavalry; others bore helm and lance and breastplate, as well as the national bow. Of infantry the Parthians had none, save levies raised among their subject-races for operations in mountainous regions. When the fight was to be in the plains, they did not take a single foot-soldier with them. Of all the regions of the border, Mesopotamia, into which Crassus was now advancing, was most suitable for the tactics of the enemy: the battles would be fought among rolling sandy downs, destitute of trees, and crossed by rivers at very unfrequent intervals.

Confident in his seven legions and his 4000 horse, the triumvir marched out from Carrhae and entered the desolate lands that lay between his base and the Parthian capital. He had resolved to take the shortest route to Seleucia, in spite of the advice of his Armenian allies, who had endeavoured to induce him to draw near to the Tigris and the Assyrian mountains, instead of plunging into the Mesopotamian sands, where the Parthians could use their horsemen to the best advantage. Tradition tells that he had been influenced in his resolve by the treacherous advice of an Arab sheikh named Ariamnes (or Abgarus), who had told him that speed was the essential thing in his advance. For, as he alleged, the Parthian king was not intending to fight so near the Roman frontier, and was sending his treasures eastward and preparing to evacuate Seleucia without any serious attempt to make a stand.

If Crassus was gulled by these stories, he was soon undeceived, for on the second day of his march his vedettes were driven in by the Parthian horse, and reported that the vizier Surena was close at hand with a mighty host. Eager to engage, the triumvir pressed on to meet the enemy, in full expectation of a victory that should eclipse all that Pompey had ever accomplished in the East. At first he drew up his men on a very long front, the legions deployed in line, with the cavalry in equal halves at each end of the array. But presently it struck him that this formation did not sufficiently cover his enormous baggage train, which was trailing along for many miles to the rear. Accordingly he changed his order to a great hollow square, and placed all his impedimenta in its centre. This would have been an excellent battle formation had he been about to contend with an enemy who employed “shock tactics,” and intended to charge in upon the legions, but against horse-archers it was a mistake; it gave them a target which it would be impossible to miss, and at the same time made it hard for the Romans to charge without breaking their order of battle. The square is an essentially defensive formation, and useless against a light and evasive foe who has no wish to close.

When the Parthians appeared, at first in comparatively small numbers, but afterwards in huge hordes that seemed to cover the whole horizon, Crassus (in the usual Roman style) sent out his light troops to skirmish. But his slingers and archers were but a few thousand strong; after a short combat they were flung back upon the legions with heavy loss, absolutely overwhelmed by the concentric arrow-shower which was poured in upon them. The pursuing enemy then began to ride close up to the great square, and to take easy shots into the mass. They kept at a discreet distance, some 200 yards or so, and the legionaries were helpless against them, for the pilum had but a short range, and could not reach the horsemen. Nor was it any use to advance, for the enemy slowly retired, keeping always at the same distance from the legions, and continuing to pour in his long deadly shafts, which “nailed the shield to the arm that bore it, and the helmet to the head.”

Crassus now began to see the difficulties of the situation. Since it was impossible to contend with missile weapons against the Parthians, it was necessary to close at all costs. Accordingly he gave his son Publius charge of 1300 cavalry — all Gallic veterans fresh from Caesar’s wars, 1 500 archers, and eight picked cohorts of infantry, and bade him sally out from the square and charge desperately into the enclosing ring of bowmen. Before this sudden onset the Parthians gave way, retiring at full speed, and leaving a moment’s respite to the harrassed legions. Young Crassus pursued them fiercely, his infantry pushing forward so rapidly that it almost kept pace with the horsemen. Apparently the young commander allowed himself to be carried away by the ardour of the charge, and entertained a vain hope of catching up the enemy, for he chased them for five or six miles, till he had got quite out of touch with his father’s legions. Then he suddenly found himself face to face with the solid supports of the elusive horse-bowmen — heavy squadrons of mailed lancers, who met him in orderly array and offered battle. At the same moment the fugitives whom he had been chasing halted, and began to ply their bows from the flanks. Although his troops were much dis ordered by their long and reckless ride, Publius charged straight at the centre of the enemy. A furious mtilde followed, but the Romans were hopelessly outnumbered, and after a most gallant defence the whole detachment, horse and foot, was exterminated.

The triumvir, advancing slowly in his son’s track, was horrified to meet the Parthians returning with shouts of triumph, and displaying the heads of Publius and the other fallen officers fixed on their pikes. But, with a resolution which shows that the old Roman spirit was not dead in him, he addressed his men, crying ” that the loss of his son was his own private concern, and that the main army was intact, and might yet retrieve the day and avenge their fallen comrades. No campaign could be carried to a successful end without some casualties. It was not by her good fortune, but by her perseverance and fortitude in adversity that Rome had risen to be the mistress of the world.” These words were not enough to stir the weary soldiery, who had thoroughly lost heart, and were already cursing the general who had led them into this snare in the desert. It was his ignorance and presumption, they complained, which were the causes of their present desperate condition. They held out sullenly till dusk came, but when the fall of night compelled the Parthians to withdraw, the whole army, officers and soldiers alike, demanded to be led back to the Euphrates. A deputation went to seek for the proconsul, who was found stretched on the ground, with his head wrapped in his cloak, mourning for his son. Since he seemed sunk in a dull apathy, and refused to issue any orders, the quaestor of Crassus took it upon himself to bid the army decamp under cover of the night, and make a forced march for Carrhae. The baggage and 4000 wounded were left to the mercy of the enemy.

A night retreat is always fatal to troops who have lost their nerve, and the Romans, dropping with fatigue and wearied by twelve hours spent under arms, had no longer the power to move rapidly or to keep their distances. When day broke, they were found straggling across the plains in half-a-dozen disjointed columns, each of which had to shift for itself. The Parthians came up a few hours later and beset the retreating army. Some of the more belated corps and multitudes of the stragglers were cut up, but the main body reached Carrhae in the afternoon.

Next night Crassus again commenced to retreat, for his troops were so demoralised that he felt sure that it was hopeless to make any stand east of the Euphrates. The second day of flight was as disastrous as the first ; the troops lost all touch with each other, and the greater part of the horse, leaving the infantry in the lurch, never drew rein till they had saved themselves in the mountains. Crassus himself, with only four cohorts in his company, was worried all day by a swarm of horse-bowmen, who succeeded in intercepting his way to the hills, and finally compelled him to halt and stand at bay on an isolated eminence just outside the limit of safety. Then followed a miserable scene of treachery. The Parthian vizier came up, and seeing that it would be hard to storm the hill, proposed a conference, holding out prospects of granting a peace, on condition that Crassus should order the evacuation of the Mesopotamian cities and retire beyond the Euphrates. The soldiery hailed with joy a proposal that promised a relief from their present desperate condition, but the triumvir himself was not deluded, and warned all those about him that the only safe course was to hold out till night, and then make a dash for the hills through the lines of the enemy. His exhortations produced little effect, and seeing that his men were utterly demoralised and unwilling to fight any longer, he consented to go down and treat. It is said that he took his officers to witness that he went to his death with his eyes open, but that for the credit of Rome “it would be better to say that the general was deceived by the enemy rather than that he had been abandoned by his own men.”

The sequel was exactly like the scene at Caubul in 1841, when the unfortunate Macnaughten went down to treat with Akbar Khan. Crassus and his escort were received at first with ostentatious respect, and a conference was begun. Presently a feigned scuffle was got up, and hands were laid upon the proconsul, whereupon one of his legates drew his sword. This acted as the necessary signal for open violence, and Surena’s attendants fell upon the Romans and despatched them every one. Crassus’s head was cut off and sent to Seleucia to be laid before the great king. Every one has read of the scene that followed the arrival of the ghastly trophy, a scene that illustrates accurately enough the curious admixture of savagery and civilisation at the court of the Arsacidae. King Orodes was witnessing the Bacchae of Euripides, wherein King Pentheus is torn to pieces by the frantic Theban women. The actor who was playing Agave seized the head of Crassus, and used it instead of the mask that represented the head of Pentheus in the wild dance at the end of the play. Orodes was charmed with the idea and presented the tragedian with a talent of silver.

We must not blame Crassus too much for the disaster of Carrhae. Probably any other Roman general of the day, with the possible exception of Caesar, would have suffered a defeat under the same circumstances. For the Parthian method of war was utterly unknown to the Romans, and the legion, a splendid weapon against any other foe, was useless here. In later campaigns, profiting by Crassus’s experience, the generals of the West never attempted to attack the Parthian in the open with an army of the old Roman type. They took into the field large bodies of cavalry and tens of thousands of foot-archers. These last proved especially successful against the troops of the Arsacidae, for the Parthian bow, having to be used on horseback, was necessarily short, and was out-ranged by that of the foot-soldier. Hence the Orientals had the choice between being overmatched in archery and being forced to charge home. In both cases they usually fared ill when engaging with the Romans. There never was a second Carrhae, but it is hard to see how the first could have been avoided.

It was a strange and inappropriate end to the life of Crassus that he should go down to history with his name attached to an error in military tactics, rather than to some political or financial fiasco. But a certain inevitable futility attached to all that he undertook. He wanted power, and thrice in his life the power was placed within his hand. But when he had it, he could not use it, for he was equally destitute of an ideal and of a programme. Even if Pompey had not always been at his side to check his ambition, we see that he would never have achieved anything great. The story of his career shows just how much and how little mere wealth, ambition, and industry, without genius, an inspiring personality, or an honest enthusiasm could accomplish in Roman politics.

_______________________

[1] From Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable: “The Romans used to twist straw round the horns of a tossing ox or bull, to warn passers-by to beware, hence the phrase foenum habet in cornu, the man is crotchety or dangerous.” [ed.]