Editor’s note: The following comprises the eighth chapter of Seven Roman Statesmen of the Later Republic, by Sir Charles Oman (published 1902).

VIII. Pompey

In Cato we have had to deal with a man who should have been born in an earlier age, who knew it, and who went through life with his eyes open, fighting against the inevitable, though he knew that it must come in spite of all his striving. Now we have to survey a still more unhappy and pathetic career, that of a man who did not even know the signs of the times, and went on blindly seeking he did not quite know what, and doing infinite mischief just because he did not know what he wanted.

There have been, alike in ancient and in modern history, great generals who were also great statesmen, for good or for evil, like Caesar, or Frederick the Great, or Napoleon. There have also been great generals to whom all insight into the verities of contemporary politics was denied, and who yet insisted upon interfering in them, and found it easy to do so. For the multitude is always prone to credit great generals with universal genius in statecraft, just as it is equally prone to credit great orators with the same faculty. For it seems to be easy to forget that excellence in strategy and in oratory are about equally remote in character from excellence in statesmanship. Cicero or Burke, not to mention more modern names, cut poor figures as practical politicians, but even more pathetically futile are the great men of war who have been put at the head of the state by their admirers, and have gone astray in the Forum. The best example in modern times is probably our own Wellington, whose mismanagement had no mean part in bringing England to the edge of that revolution which she only escaped by the great Reform Bill of 1832. The best example in ancient history is undoubtedly Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, three times the potential master of Rome, who thrice refused to lay firm hold of the helm that was thrust into his grasp, and yet could never quite keep his fingers from itching to handle it. Never did a man’s virtues combine more fatally with his weaker qualities to bring about not only his own ruin, but the wreck of his country. A sternly stoical and self-repressing Pompey would have crushed down the ambition in his heart, and steeled himself to despise any misrepresentation and injustice that fell to his lot, like Phocion of old. He would have done the Republic no harm, though he might not have proved its saviour. On the other hand, a purely self-seeking and unscrupulous Pompey would have been able to seize the control of the state with ease, and might have tried whatsoever constitutional experiments he pleased. Perhaps the Republic might have fared none the worse if he had done so; he might have become its ruler without the civil war which Caesar had to face. His opportunities were far better than those of Caesar for gaining supreme power, without having to wade to the throne through oceans of Roman blood.

But Pompey was neither wholly unselfish nor wholly unscrupulous. Hence it came to pass that he took neither of the alternative paths, but fidgeted about between the two, sometimes obeying the impulse of ambition, some times that of loyalty, so that all his actions seem incoherent and inconsequent, and the general trend of his career appears both destructive to the constitution and disastrous to himself. Yet it is hard to grow very indignant with him; his personal virtues are too conspicuous, and his character too far above the level of the other Romans of his time. He was so ungratefully treated by those he fain would have served, and his final end was so piteous, that we are forced to shut our eyes to the mischief (mostly unintentional) which he did, and to view his whole life with sympathy rather than with impatience.

It is hardly necessary to say that Mommsen’s estimate of Pompey is no more to be taken seriously than his estimates of Cicero, or Cato, or Caesar. It is as misleading to treat him as a mere drill-sergeant, as to call Cicero a “fluent Consular,” or Cato a “mere Don Quixote,” or Caesar a beneficent and unselfish saviour of society. He was in reality no military pedant but an excellent general and organiser. In war he fared well, save when he came in contact with the two men of first-rate military genius who crossed his path, Sertorius and Caesar. Against them he fought not ingloriously, till the fatal day at Pharsalus, when he for the first time met with complete disaster, ruined not so much by his own fault as by the rashness of his officers and the inexperience of his men.

But it was not so much as a soldier that Pompey appeals to the student of those last troublous days. In that time of corrupt and degenerate Romans it is a relief to come upon a leading man who was neither a profligate nor an unscrupulous adventurer. Pompey’s private life was worthy of the old times of the Republic for its modesty, honesty, and purity. No one ever accused him of greed, of debauchery, or of malevolence; “he was the slowest man at asking and the readiest at giving in Rome,” says Plutarch. Nor was he merely honest and upright; he also possessed the virtue — rare above all others in that age — of humanity, shown not only to fellow-citizens, but even to foreigners and enemies. In all his Eastern and his Western campaigns, one of the most remarkable points is his habitual kindliness and moderation to the vanquished. Not only open foreign foes, but even outcasts, like the pirates of Cilicia, found in him a merciful conqueror. Any other man would have crucified those robbers along the coasts which they had plundered. Pompey turned them into colonists in his new cities in the Isaurian region, where, strangely enough, they repaid his confidence by turning out good settlers. Even the Jews, whose feelings he had outraged by forcing his way into the Holy of Holies at Jerusalem, speak nothing of him but good. Of all Roman conquerors he was undoubtedly the most just and merciful. He had not, like his rival Caesar, huge stains of massacre upon his reputation, such as the execution of the senate of the Veneti or the treacherous slaughter of the 430,000 Usipetes and Tencteri. He would have been wholly incapable of that worst act of all, the saving in prison for six years of such a gallant enemy as Vercingetorix, in order that he might be duly led in chains and put to death in the Tullianum, when his callous victor’s long-delayed triumph should take place. No one ever could accuse Pompey of deliberate and cold-blooded cruelty of such a cast as this. The only captives that Pompey ever slew were Romans and traitors, men whom it might have been profitable to spare, as Caesar might very possibly have done, but whose crimes he thought too great for pardon. We shall have to tell the story of the deaths of Carbo, of Brutus, and of Perpenna in their proper places.

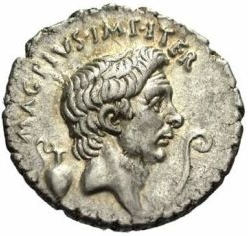

Gnaeus Pompeius was born in B.C. 106. He was the son of Gn. Pompeius Strabo, a man of equestrian rank, who had (first of his house) raised himself to consular office by his military achievements in the great Social war with the revolted Italians. Thus Pompey, though not a novus homo himself, was the son of one. Their family seems to have been for some time settled in Picenum, where we find both the father and his son after him exercising great local influence. Strabo, though a man of good abilities, had a sinister reputation. He played a rather equivocal part in the first year of the civil war between the Optimates and the Marians. He was more than suspected of having been privy to the murder of his rival, Pompeius Rufus, in a military sedition. When he finally espoused the side of the Senate, it was mainly because he was forced to do so, since he could no longer play fast and loose with both parties. He died in the middle of the war [B.C. 87] while commanding for the Senate against Marius and Cinna. We are told that his own soldiers (who wished to join the Democrats) conspired against him, and that his life was only saved by his son’s courage and vigilance. But a few days after he is said to have been struck dead by lightning in his tent. Knowing that his men were plotting against him, and that they actually tore his body from the bier and dishonoured it, we shall perhaps not be wrong in substituting “was murdered” for “was killed by lightning.” There are other cases in Roman history of unpopular generals who are said to have met their death from a thunderbolt, and all are equally suspicious.

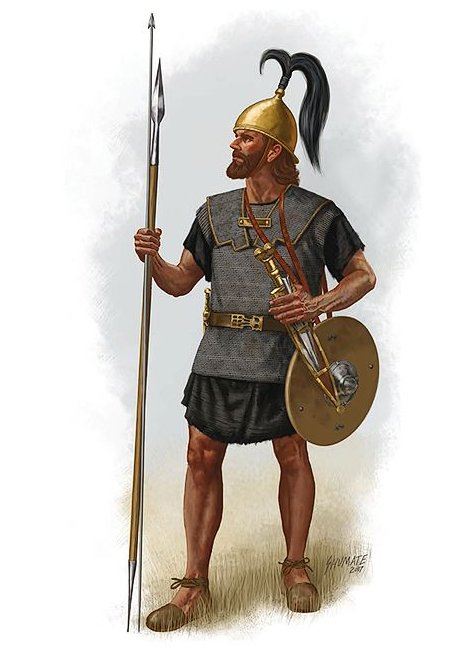

Strabo’s son, Gnaeus the younger, was marked out for slaughter by the Marians as his father’s heir, though he had only reached the age of nineteen. For some months he concealed himself, but after Marius’s death, when the massacre was dying down, he was discovered and indicted by the minions of Cinna, on a charge which might have proved fatal, if the praetor Antistius, a powerful man at the moment, had not protected him, and saved him, on the condition that he should marry his daughter Antistia. Thus preserved, the young man was able to remain safe but obscure till the year B.C. 83, when Sulla landed in Italy to attack the Democrats. It was then that the future triumvir first showed the stuff that was in him. Hastening to his father’s native district of Picenum, he raised a considerable body of followers, before any one else in Italy had taken arms for the Optimate cause. He displayed extraordinary vigour and ability for one so young and so new to command. With very inferior forces he kept in check a large Marian corps, while Sulla was contending in Campania with the main body of the enemy. He defeated the praetors Brutus and Carrinas, and finally cut his way south, and joined Sulla at the head of an army which had swelled to no less than three legions. All the other Optimate refugees had come to Sulla empty-handed. Pompey brought 12,000 men already tried in war, and enthusiastically devoted to their commander. Italy had never before seen such a force raised by a private person, a young man who had but just reached the age of twenty-four. It was only natural that the Optimate chief honoured Pompey more than any other man of his party, saluted him as Imperator, and gave him precedence over all his other officers, though he was technically no more than a simple knight, and was barely qualified by his age to stand for the quaestorship. In the later years of the civil war Pompey won a reputation which was approached only by those of Crassus and of Ofella, and he was trusted far more than either of his rivals by Sulla. As a shrewd judge of character, the dictator could see that the young man, whatever his faults, was at least honest. Hence it came that when the flames had died down in Italy, he, rather than any other officer, was entrusted with the important task of rooting out the Democrats from Sicily and Africa. Though given but a small army, he accomplished his work with extraordinary vigour and skill, and a not less notable humanity. Sulla’s legions did not always shine in the matter of consideration for provincials; they had been trained by their chief to regard anything as permissible. It is all the more creditable to Pompey that he kept them in such order that no town in Sicily was sacked nor any of the inhabitants harmed. He is said by Plutarch to have actually caused his soldiers’ swords to be sealed down in their sheaths, after the fighting was over, that they might not use them against the Sicilians. But this odd statement looks like a translation into prosaic fact of some rhetorical flourish, which the simple old Boeotian had read in a panegyric of Pompey.

Crossing from Sicily to Africa, the young general easily routed Domitius and the large Democratic army which held that province. It a few weeks it was completely subdued. Only one man’s life taken in cold blood marred the lustre of these triumphs. The single person whom Pompey executed was the leader of the whole Democratic party, Carbo, who fell into his hands in the isle of Pandataria, half-way between Sicily and Africa. On Carbo’s head lay the responsibility for the whole of the late massacres in Rome, and Pompey owed him the personal grudge that in that slaughter had fallen his father-in-law, Antistius, the friendly praetor who had saved him in B.C. 87. Moreover the ex-consul was an outlaw by the decree of the people, and the chief of all Sulla’s enemies. It was probably kinder in the end to slay him on the spot, than to send him to Rome to face Sulla’s wrath and to suffer some elaborate punishment for his misdoings; but we may share with Pompey’s friends of that day the regret that he took a part in the execution of even such an unpardonable enemy of the Optimate cause as Carbo.

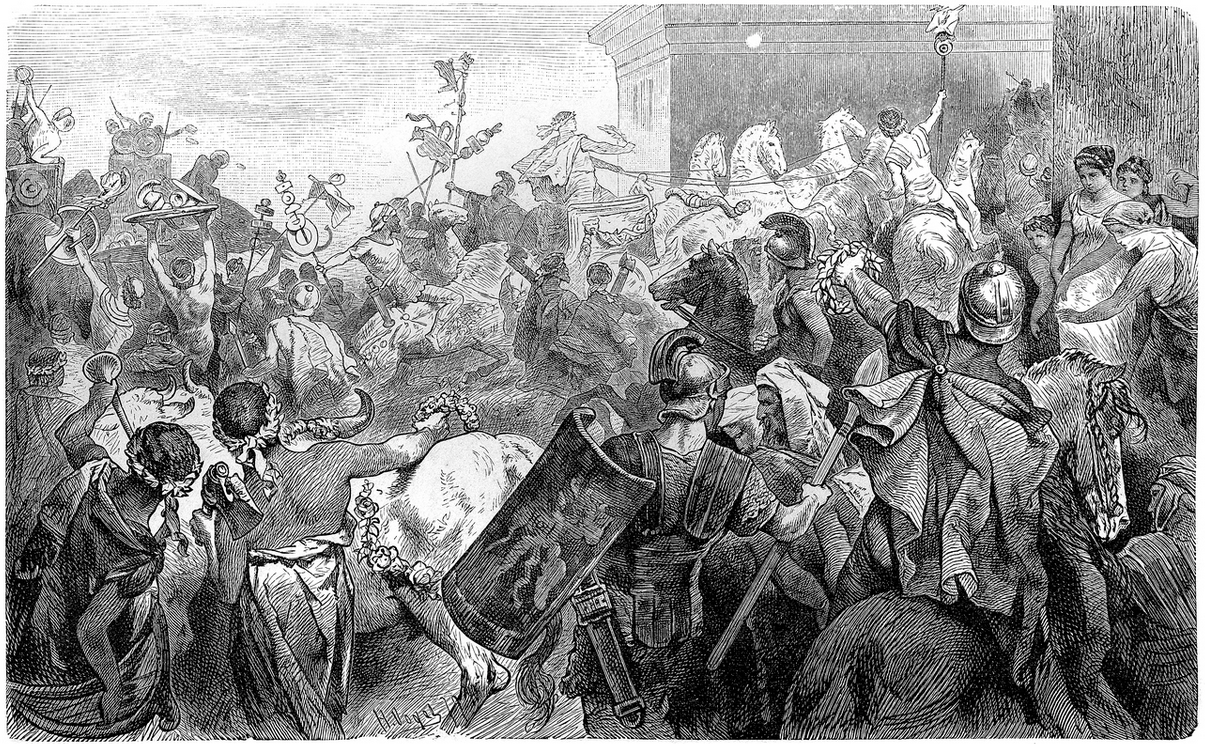

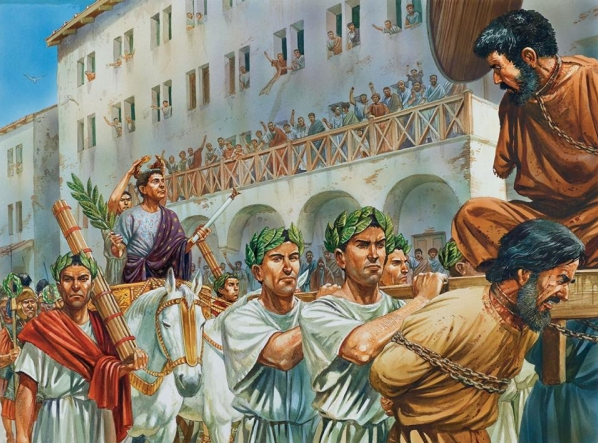

On returning to Rome victorious in B.C. 81, Pompey was granted a triumph by Sulla though he was still technically a “private person,” for he was an eques, not a senator, and held no office but that of legatus to the dictator. This is said to have been the only case in Roman history in which a triumph was granted to one who had never held any magistracy whatever. Sulla had not failed to note that his young lieutenant would be too much elated by his splendid position to bow readily to the new régime. It was a great thing to ask of one who had a victorious army at his back that he should step down from his triumphal car to take a modest place among the younger Optimates. But though Pompey was not destitute of ambition, he had from his earliest youth a singular dislike for violence and illegality. He duly disbanded his army and settled down in Rome as a private person without making much ado. This so much pleased the dictator that he saluted him by the name of “the great” — Magnus — the only cognomen which he ever bore, since he never took his father’s unflattering name of Strabo — ” the cross-eyed.” Having once convinced himself that the young general could be trusted, Sulla allowed him liberties which he granted to no one else; not only did he concede him his abnormal triumph, but he even allowed him to support for the consulship of B.C. 78 the vain and heady M. Aemilius Lepidus, a man whom (rightly enough) he distrusted. He did not interfere with the canvass, but merely warned Pompey that he had acted with grave unwisdom. “You are proud of your victory,” he said, as the train of the new consul swept through the Forum, “but be on your guard. You have used your influence and popularity to put a worthless man in power. Thereby you have raised up an adversary and made him stronger than yourself.” Lepidus’s subsequent conduct entirely justified the dictator’s forecast. But it must be confessed that Pompey’s political judgments all through life were invariably ill-advised: this support of Lepidus was but the first of a long series of mistakes.

After Sulla’s death in 78 the new consul — freed from the wholesome restraint of fear which lay upon every ambitious man who remembered the fate of Ofella — broke out in open revolt against the constitution. He came forward with a programme of public bankruptcy (novae tabulae) combined with the restoration of the Democratic constitution: to back his reckless schemes he secretly raised an army of outlaws and swash-bucklers in Etruria. Pompey had to take arms against the man whom he had so unwisely placed in power. He was given an army to clear the east coast of Italy and Cisalpine Gaul of the insurgents, while Catulus dealt with the main body and the rebellious consul himself. How the latter was routed in the Campus Martius when he made his reckless assault on the capital we need not again relate. Pompey was at the moment in the north, dealing with Lepidus’s lieutenant, M. Brutus (the father of the tyrannicide of B.C. 44); after beating him in the open field he shut him up in Mutina, and pressed him so hard that he surrendered, in order to prevent his own army from delivering him over to the besiegers. In spite of this voluntary submission of the Democratic chief, Pompey, after a day’s hesitation, put him to death, and with him Aemilianus, the son of Lepidus. This was of all Pompey’s doings, the one that was most criticised during his lifetime. He had accepted the surrender of Brutus, spared his life, and sent him away in custody. Then, on mature reflection, and after composing a despatch to the Senate in which he announced the capture of Mutina, he put to death his prisoners in cold blood. No one could dispute that Lepidus and all his crew were public enemies, so that there was no formal illegality in the act. But it was felt that if Pompey had intended to slay the Democratic leaders, he ought not to have received them to surrender: it would have been better for his reputation if he had sent them to Rome and allowed the Senate to do its own killing. It was true that the prisoners were factious traitors, who had stirred up a wholly unnecessary civil war, but, if Pompey felt such righteous indignation against them, that he was constrained to put them to death, it was unfortunate that only seven years later he should himself introduce and carry through several of these same Democratic reforms which Lepidus and his followers suffered for supporting [B.C. 77].

For the second time Pompey now stood victorious in Italy with a large army at his back. In spite of the unswerving loyalty to the Optimate cause which he had hitherto displayed, the Senate felt uncomfortable with such a stirring and capable general at their gates. It was with considerable relief, therefore, that they heard that he was not unwilling to undertake a new military commission, which would remove him far from the capital. He wished to be given the charge of the difficult and dangerous war against Sertorius in Spain, which had been in progress ever since Sulla drove the Democrats out of Italy five years before. Metellus, the best general of the old Optimate ring, had been striving against the great guerilla chief with indifferent success, if without actual disaster. There was no one else to send against him, least of all did the consuls of the year show any wish to set out upon such an uninviting errand. “We must despatch Pompey to Spain,” said the witty L. Philippus, “non pro console, sed pro consulibus.”[1] Doubtless the more suspicious members of the oligarchy muttered to each other that if Pompey slew Sertorius, the state was freed from a great public danger, while if Sertorius slew or foiled Pompey, there was at least a dangerous pretender removed from the political stage. So the young general was duly assigned the province of Hither Spain, and permitted to march forth from Italy, taking with him the army which had subdued the Cisalpine rebels and captured Mutina. Troubles in Gaul delayed his march, and it was not till the spring of B.C. 76 that he reached the Pyrenees, there to find that Sertorius was in possession of the greater part of the Iberian Peninsula. The tribes of the north-east were still faithful, as were most of the coast cities on the Mediterranean. But Metellus was fighting an uphill battle in Baetica, and over the whole of the interior, and the western parts of the two provinces, Sertorius reigned supreme.

The fact was that the Spanish war was no longer a struggle between the two Roman parties, nor a prolongation of the old contest in Italy between Democrat and Optimate. It was much more like a national rising of the greater number of the Iberian tribes to recover their ancient independence. The old programme of Marius and Cinna had nothing in it to attract the Spaniards, and Sertorius was not fighting for that outworn creed; he was sustained by his personal ambition and his determination not to submit to the oligarchy. It was as a Spanish chief, not as a Roman propraetor, that he was now strong; the Italian element in his host was daily growing less, the native element more preponderant. The war was becoming an attempt, led by a man of genius, to found a new Romano-Spanish national state. If Sertorius was not yet wholly successful, it was because the ancestral feuds of the Celtiberian tribes always supplied his enemies with a considerable following of native supporters. Yet their number was daily growing less, as the loyal states of the interior, unsuccoured by the arms of Metellus, fell one after another into the hands of the great guerilla chief.

Spain was already the land in which, to quote the epigram of a great general of the modern world, “large armies starve and small armies get beaten.” Pompey found that he had undertaken no easy task, when he looked on the boundless arid plains and the rugged sierras over which the bands of Sertorius were roving. How was he to deal with an enemy who moved twice as fast as the heavily loaded legion, who knew every pass and ravine, who dispersed when beaten, yet assembled within a few days to fall upon the victor’s flanks and rear. The army of the rebels, it was said, was like one of their own rivers. At one moment Sertorius would be wandering lost in the plains with a handful of followers, like a meagre July stream; at the next, like the same stream after rain, he would be dashing along swollen by countless fierce affluents from the mountains, almost irresistible, with 150,000 spears at his back.

For five years the weary struggle with the Spaniards continued [B.C. 76-72] amid many alternations of fortune. If Pompey had hoped to win an easy triumph over enemies no more formidable than those he had encountered in Italy and Africa, he must have been disappointed. Many times he was foiled, once he was defeated in open fight: on another occasion he owed it to the arrival of his colleague Metellus that he ended the day with a drawn battle instead of a defeat. But his spirit never failed, nor did his legions waver from their belief in him. The Senate supported him badly, as might have been expected: there was a moment when the pay of his soldiers was two years in arrear, and when he had used up the greater part of his private fortune in making advances to his loyal followers. But in spite of the neglect of the home government, the difficulty of the country, and the unrivalled mixture of craft and courage displayed by his adversary, he worked on slowly towards his end. Many historians have sneered at Pompey’s management of the war, and have hinted that a general of ordinary capacity would have brought it to a much earlier end, without any of the “unfortunate incidents” that chequered its earlier years. We, who have learnt of late what guerilla warfare means, shall be loth to condemn him when we reflect on the superior numbers of his enemies, on the character of his troops, almost entirely infantry, and on the slack way in which he was supported from home. He never despaired, even when the struggle had dragged on for four years: he slowly drove back Sertorius into the inland: when at last that great man fell by the hands of his own discontented followers, he brought the war to a sudden end in a few months. It would have ceased long before, if the rebels had not possessed such a splendid leader. Perpenna, the double traitor who had murdered Sertorius, fell into Pompey’s hands in the last decisive battle. To save his life even for a few days he offered to place in his captor’s hands the private correspondence of his late chief, containing many letters of the most compromising sort from prominent men at Rome. Pompey burnt the papers unread and consigned Perpenna to the headsman. He might have crushed the malcontents by producing their treasonable correspondence, or have made them his humble servants by threatening to divulge the documents if they thwarted him. But such methods were far from his honest mind.

Leaving Spain at last pacified, Pompey set out for Italy in the spring of B.C. 71. On his return journey he was fortunate enough to run into the midst of the wrecks of the army of Spartacus. After their defeat by Crassus, and the death of their leader, the rebels were flying towards the Alps, but met the Spanish legions in Liguria and there were cut to pieces.

It was now for the third time that Pompey came victorious to the gates of Rome, with a loyal army of veterans who would have followed him on any enterprise. Sulla’s troops, who came over from Greece in B.c. 83, were not more devoted to their leader or more ready to attack any enemy that he might point out to them. The Senate might well tremble, for they had done their best to provoke Pompey, by their culpable neglect of the Spanish war and their persistent refusal to grant money and reinforcements to him for the last five years. They had no force to oppose him, for Metellus, the other commander in Spain, had disbanded his legions, and Crassus, who had put down the Servile revolt, was known to be even worse disposed toward the Senate than Pompey himself. There were only three possible ways out of the situation. The two generals — old personal enemies, as we have seen when dealing with the life of Crassus — might fall to blows and fight for the sovereignty of Italy; or one of them, in jealousy of the other, might espouse the cause of the Senate; or they might agree to sink their private enmity and join in an attack on the Optimates and the constitution of Sulla.

As we have already had to relate, it was the last and the least likely of these three alternatives that came to pass. Pompey did not attempt to fight his way to supreme power across the body of his rival Crassus, but joined with him to overthrow the Senate. He had long seen that the Sullan constitution was too narrow and cramping for a man of his own ability and ambition. He was flattered by the almost universal applause which he had won by ending the lingering war in Spain; flattered all the more, perhaps, because it must be confessed that Perpenna’s dagger had given him the final triumph almost as much as his own sword. He owed the Senate no gratitude; a great body of the enemies of the Optimates — the rural knights and municipal Italy in general — were ready to welcome him as their natural leader. Hence came his definitive acceptance of the place of leader of the anti – senatorial party, and his alliance with Crassus. Probably he was in the end unwise to make their cause his own; he was reopening the floodgates of Democracy, when a Democratic constitution was really more unsuited to him than the rule of an oligarchy. He was, in truth, by virtue of his orderly mind, his rather stolid virtue, his practical ability, uninspired by any spark of erratic genius, much more fitted to be the trusted general of the aristocracy than to be the leader of the turbulent mob of Rome. His reserved manners and his slow and uninspiring speech were enough in themselves to handicap him for the career of a Democratic politician. But since the Fathers, much as they feared him, showed no wish to enlist him as their champion, while their opponents were eagerly imploring him to become their chief, he finally made the plunge and stood for the consulship along with Crassus in the character of “the friend of the people.”

How he and his colleague abolished the laws of Sulla, and how they quarrelled from the first day to the last of their joint magistracy, we have already told in another place. When their office ran out, both appear somewhat stranded on the shore of politics. The position of an extemporised party leader when he has carried out his programme is always uncomfortable. It is often for gotten that Pompey sat quiet for two whole years [B.C. 69-68] after laying down his consular fasces. If any further proof had been needed to convince his friends and his enemies that he aspired to be the first general of the Republic, but not its master, this voluntary retirement should have sufficed. A would-be tyrant would not have spent so long a time without meddling in politics. Pompey was seldom seen in the Forum, or indeed in any public place. When he did appear, it was always with a considerable train of friends and clients who kept off from him the attentions of the populace, ” for he hated the familiarity of the many, and thought that true dignity is soiled by their touch.” Instead of playing the demagogue and keeping himself perpetually in evidence, he lived quietly at home with his wife Mucia and the three children that she had borne him. We need not say with Dr. Mommsen that he was playing at this time “the empty part of a pretender who had resigned his claims to a throne.” Clearly he had never wished for that throne, and was contented to dwell in Rome as her greatest citizen, till a crisis should again arise which might call him once more into the field as her greatest general. In B.C. 69-68 no such crisis existed; the second Mithradatic war seemed to be going well in the capable hands of Lucullus, and there was no other trouble on hand which was important enough to call forth Pompey from his retirement.

In B.C. 67 things began to change. The exploits of Lucullus ended miserably in the revolt of his legions and the loss of all his conquests. The army of Triarius was cut to pieces at Ziela, and the light horsemen of Mithradates once more appeared on the border of the Roman provinces. At the same time a famine began to rage in Rome, caused partly by a bad season, but much more by the depredations of the pirates, who at this moment were playing a more prominent part than ever before in Mediterranean politics. Purporting to act as the allies of the King of Pontus, but really plundering for their own profit, they were making every sea unsafe, and even daring to make flying descents on Italy, where Spartacus had first invited their presence and made them welcome. Though their base of operations lay far to the east, in Crete and Cilicia, they were habitually to be found cruising off Spain and Narbonese Gaul. Since the incapable M. Antonius Creticus had failed in his attempt to put them down in B.C. 74, they had been practically left unmolested by the Roman state, and the boldness caused by this impunity was making them almost as daring as those Algerine rovers of the seventeenth century, whose voyages extended as far as Kinsale and Reikjavik. The Senate might yet have remained torpid, had it not been that the non-arrival of the African and Egyptian corn-fleets in a year of dearth drove the people to riots and outbreaks which could not be disregarded.

Something had to be done, but this something might have been nothing more than the appointment of one more aristocratic incapable to raise a fleet, if public opinion had not intervened. The moment that an expedition against the pirates was mooted, there was a general cry for Pompey, the one available commander whose efforts were always crowned with success. The Democratic leaders of the day, Quinctius, Gabinius, and the young C. Julius Caesar, were quick to grasp the spirit of the times, and saw that an attack on the Senate for its maladministration must be accompanied by a pro posal to place the charge of the Pirate war in the hands of the man whom the people trusted. Hence came the sudden and vehement agitation for the appointment of Pompey to a special command against the pirates, which took shape in the Gabinian Law of B.C. 67. He himself is said to have shown no great enthusiasm for the proposal, and to have required much pressure before he lent it his support. There is no reason to accuse him, as does Dr. Mommsen, of hypocrisy. He had no great knowledge of naval affairs, and may have doubted his own capacity to deal with a maritime problem. Moreover, the pirates must have seemed a despicable enemy to one who had contended with Sertorius. Nor is it to be forgotten that Gabinius and Caesar were no friends of Pompey, and that they were both regarded as rather reckless and disreputable politicians. It may have displeased him to receive a boon from such hands, and to feel that his popularity was being exploited for the benefit of a pair of demagogues. It is at all events certain that he studiously kept out of the agitation, and even withdrew from Rome on the day when the Gabinian Law was put before the assembly. Evidently he wished to show that the command was unsolicited by him, and that if he accepted it he only did so in deference to the strongly expressed wish of the people.

The bill, indeed, was somewhat startling in its details. There had been previous grants of a special commission to various generals, and the imbecile Antonius had seven years before been given a command of this same sort against the pirates. But the Gabinian Law was on a much larger scale than anything of the kind that had been seen before. Pompey was to be given the aequum imperium over all Roman territory that lay within fifty miles of the sea — i.e. he was to possess equal power with all other provincial governors in their own spheres throughout the greater part of the empire. For there was not a province whose larger half was not situated within the prescribed distance from the shore: the Roman empire was still essentially a domination over the Mediterranean littoral, and the broad inland was for the most part still unconquered. To control such a wide-spreading field of action, Pompey was to be granted twenty-four lieutenants of senatorial rank, whom he might select for himself : each of them was to be given praetorian power and insignia. A magnificent grant of money, no less than 144,000,000 sesterces, or £1,350,000, was set aside for his military chest. He was authorised to raise men and ships up to any amount that he chose — as far as the enormous figures of 120,000 men and 500 galleys. As a matter of fact, he did not find it necessary to levy anything like so large a force. The term of his command was to be for no less than three years. For a man who wished to be king, all the essentials of a military monarchy were thus provided. But Pompey had no desire for throne or diadem, and this (we can not doubt) was well known to shrewd observers of his character like Caesar and Gabinius, or they would not have put the temptation in his way. It was not so obvious to the Optimates, who made as loud and frantic a protest as if a tyrant was being openly voted into the Capitol. They urged that the command was too extensive for one man, and that a colleague should be appointed to take some of the burden off the great general’s shoulders. We are invited to believe that when Roscius Otho urged that Pompey should be given a colleague, the roar of “No!” was so loud that a bird flying above fell down stunned upon the heads of the citizens. Nor was it to any effect that the oligarchic tribune Trebellius was induced to interpose his veto. Gabinius scared him by threatening to deal with him as Tiberius Gracchus had dealt with Octavius sixty-six years before, and when he saw the tribes actually called upon to vote for his de position, Trebellius collapsed and withdrew his proposed veto. As a last move the Optimates strove in vain to get Pompey given lieutenants nominated by the Senate instead of by himself — an ingenious way of seeing that his orders should not be too zealously carried out. The proposal was rejected with scorn.

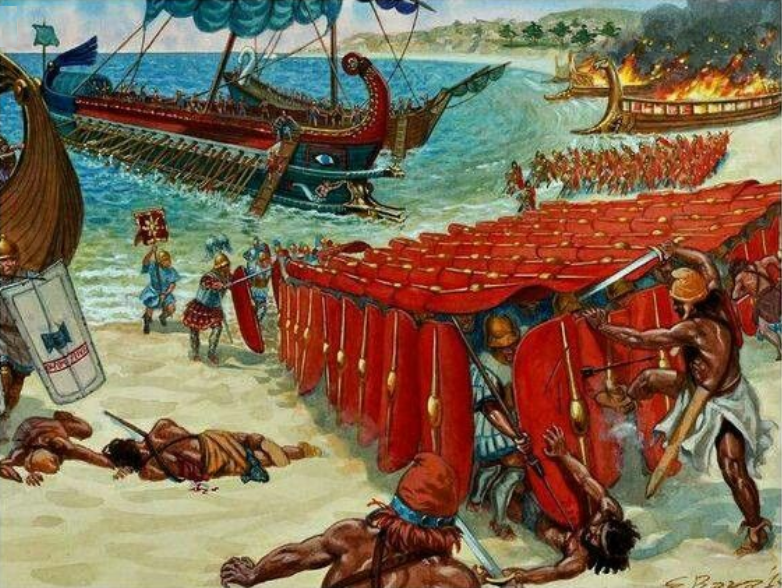

The Gabinian Law, therefore, was passed, and Pompey received carte blanche to deal with the pirates as might seem best to him. It is easy to detract from the credit which he received for the very thorough way in which he executed his commission. His enemies have taken care to point out that the fighting power of the corsairs was insignificant compared with that of the Roman empire, and that they had only survived so long because they had hitherto been opposed by commanders of approved incapacity. “The suppression of the pirates was a great relief to the state, but not a great achievement,” writes Dr. Mommsen; “it was a naive proceeding to celebrate such a razzia as a victory.” But this is not the true way to look at the campaign; a war is not easy merely because the enemy is not able to face the assailant in a pitched battle. To make an end of a swarm of guerillas is no light matter, and the guerilla at sea is even more hard to catch than the guerilla on land. Pompey’s suppression of the corsairs was a triumph of organisation and ingenuity. He mapped out the Mediterranean into districts, and set moving at the same moment thirteen separate squadrons, which all worked together and played into each other’s hands. In forty days the whole of the seas west of Sicily had been completely cleared, and corn was so cheap in the Roman market that it was said that the very name of Pompey had finished the war. Then the commander-in-chief went eastward with the best of his fleet, and swept the Aegean and Levant. There was no want of fighting: no less than 400 pirate ships, of which ninety were fully equipped war-galleys, were captured. Ten thousand of the corsairs were slain in battle; twice as many were captured. The fastnesses of the Cilician coast were one and all destroyed. Tens of thousands of prisoners were set free; immense quantities of plunder recaptured. The sea was freed from robbers as it had seldom been before since the beginning of authentic history. These are not achievements at which it is reasonable to scoff; but perhaps the most creditable item of the whole campaign is the fact that Pompey did not massacre his prisoners, but turned them into successful colonists in the maritime towns which he restored to life, Mallus, Adana, Dyme, and his new foundation of Pompeiopolis-Soli. No Roman commander before him had done the like: even Caesar in the succeeding decade used the axe and the rods with cruel severity upon many a conquered foe. He knew no mercy save for Romans and citizens, while Pompey spared even the corsairs, whom any other general would have doomed to the cross.

The Gabinian Law had allotted three years as the term of office of the great High Commissioner; but no more than seven months had elapsed when he was able to report that his task was complete, and that piracy was suppressed throughout the Mediterranean. In the winter of 67-66 he was finishing up his work by restoring the Cilician cities, and organising a system of coastguards to preserve the peace of the seas for the future. There is no reason to doubt that he intended to come home in the following spring to surrender his command, according to his invariable fashion: but he was not yet destined to leave the East. A bill was brought in by the tribune C. Manilius, to transfer to him the charge of the war against Mithradates and the care of all the provinces of the East. The genesis and object of the Manilian Law is rather obscure: its author was not one of the acknowledged heads of the Democratic party, but a rather obscure personage, who had just failed in some small political plans of his own, and was apparently making a bid for renewed popularity by devising a scheme which should please the multitude. He was neither a friend nor a partisan of Pompey, and certainly was not acting as his agent. But he saw that at this moment Pompey ‘s name was the one to conjure with, and that a certain amount of importance would accrue to himself if he could gain credit with the people as the advocate of their idol. His proposal was reasonable in itself: the war with the Pontic king had proved a failure: Lucullus was in disgrace: Glabrio and Marcius Rex, who were to take up the command, had done nothing that made it probable that they would succeed where their able predecessor had failed. On the other hand, there was a general belief that to make over the war to Pompey would secure its prompt and successful conclusion. So clear was this, that neither the leading Democrats nor the moderate Optimates dared to say a word against the project. Cicero, whose main aim at this moment was always to make himself the mouth piece of public opinion, gave the bill his warm support. Caesar also granted it his approval. Indeed no one save a handful of irreconcilable Conservatives ventured to oppose it, so popular was the scheme from the first moment that it was broached. It became law almost by acclamation, though there was hardly a prominent man in Rome who would really have supported it had he been free to speak his mind without fear of the multitude. Yet, as a mere measure of foreign policy, it was the best thing that could have been devised. There was no other man in Rome whose reputation would have justified him in asking for the Asiatic command. The one fortunate general of tried ability was the proper person to send against the Pontic king.

Pompey is reported to have received the news of the passing of the Manilian Law without any signs of elation, and to have replied to the congratulations of his friends by complaining that the state gave him no time of leisure, that he was hurried on from one task to another, and hardly was suffered to get a glimpse of his home, his wife and children. “It would be better to be one of the undistinguished many,” he is said to have murmured, “than to be the one Roman who was never granted a holiday.” Of course, his adversaries could see nothing but the most contemptible hypocrisy in such a speech. It is not necessary to think so badly of the man. That Pompey loved power, we cannot deny; he felt (like Lord Carteret) that it was his special avocation “to go about knocking the heads of kings and princes together for the benefit of his country.” But it is equally certain that he loved his home, and after finishing off a heavy task like the suppression of the pirates, he might reasonably repine at being sent forth without a moment’s respite to take in hand another, which might lead him to the Caucasus and the Caspian, perhaps even to the Tanais or the Erythraean Sea.

The Oriental campaigns of Pompey occupied him for very nearly five years (B.C. 66-62). It is as easy to belittle his achievements in the East as his achievements against the pirates; but to call his battles farces and his conquests military promenades is wholly unjust. The enemy who had baffled Lucullus was not to be despised; the wild tribes of Albania and Iberia were not “effeminate Orientals;” the marches through the bleak Armenian uplands and passes, or across the burning sands of the Arabian border were not simple or easy. Remembering all that Pompey did, and the apparent ease of his unending successes, the reader is prone to forget how Rome had failed before in these regions, and how she was destined to fail again. The army which he took with him was of no great strength — little greater, indeed, than that with which Sulla had conquered Greece: he never seems to have had more than 40,000 or 45,000 men. He was operating across utterly unknown country; each successive enemy whom he had to face had different methods of fighting; the devices that were useful against one were futile against another. Yet Pompey went on in an absolutely unchequered series of successes. He was as cautious as he was enterprising, as untiring as he was prudent. He never desisted from a task that he had taken in hand, but he never took in hand any task that was rash or unnecessary. When he first marched against Mithradates, the old king was in possession of his whole kingdom, and had an army that he had at last trained to face the methods of Roman warfare by endless guerilla tactics. Within a year he was not only beaten, but expelled from his Pontic realm; his host had been not only scattered, but annihilated, by a sudden and brilliant night surprise, which formed the unexpected termination of a cautious and careful campaign. When Mithradates had thought that he had been facing Fabius, he suddenly found that he had to do with Hannibal. All that was left to him was to fly over-seas to his distant dependency in the Crimea. With Tigranes Pompey did not have to fight at all: he encouraged the Parthians to assault Armenia, while he was himself engaged with the Pontic king. When he turned towards Artaxata after expelling Mithradates, the Armenian monarch, vexed by foreign war and internal rebellion, refused to fight, did homage to Rome, paid a large war indemnity, and resigned all his claims to his late conquests in Syria and Cilicia. It does not detract in the least from Pompey’s merit that this adversary was so much impressed by his mere approach, that he surrendered without a contest all that could have been asked from him after the most complete victory. Then came the turn of the wild tribes under Caucasus, who had been the vassals and the allies of Mithradates. In B.C. 65 the Roman army was pushed forward along the northern edge of Armenia, and scoured the valley of the Kur, and then by a backward sweep that of the Phasis. The Albanians and Iberians came out against the invaders in full force; they staked the fords and barricaded the passes, tried to cut off the convoys, and fell upon outlying detachments. But it was to no effect. On every occasion, and even on the most favourable ground, they were repulsed. At last they made their submission, surrendered to Pompey the golden table and bed of their king, disowned Mithradates as overlord, and swore allegiance to Rome.

Asia Minor and the lands behind it were now disposed of. Mithradates, it is true, still held out in the Crimea; but though overflowing with wrath against the Romans, he was practically powerless. It was in vain that he crushed his few remaining subjects with taxes and requisitions to raise a new army. He enrolled, it is true, some thousands of slaves and Scythians, and spoke of trying the fortune of war once more. But there was nothing to be feared from his menaces, for his troops were untrustworthy. He spoke of a wild plan of marching by land from the Tauric Chersonese to Italy, across the steppes of the Dnieper and the valley of the Danube. But this was a vain imagining; his mercenaries would not listen to the plan, and the tribes of the steppe would neither have followed him nor allowed him to pass. He was eating out his heart in impotent wrath, slaying his sons and his generals for suspected treason, and earning the bloody end that was soon to come upon him.

The Pontic king having become a negligible quantity, Pompey was able to turn his attention southward to Cilicia and Syria. These regions had been ceded to him by Tigranes, their last owner, but the king’s rule had always been disputed by the late subjects of the Seleucidae. When the last Armenian viceroy withdrew, anarchy set in; two princes, both claiming to represent the old Greek dynasty, half-a-dozen Arab emirs, a local tyrant or two, and the Jewish king from Jerusalem were filling the land with their futile strife. The Phoenician cities had declared themselves independent republics, and the tribes of Amanus were devastating every valley that was within reach of their fastnesses. Pompey saw no way out of the chaos but annexation to Rome. It would have been absurd to set up again some representative of the Seleucidae, whose fratricidal civil wars had been the ruin of Syria in the previous generation.

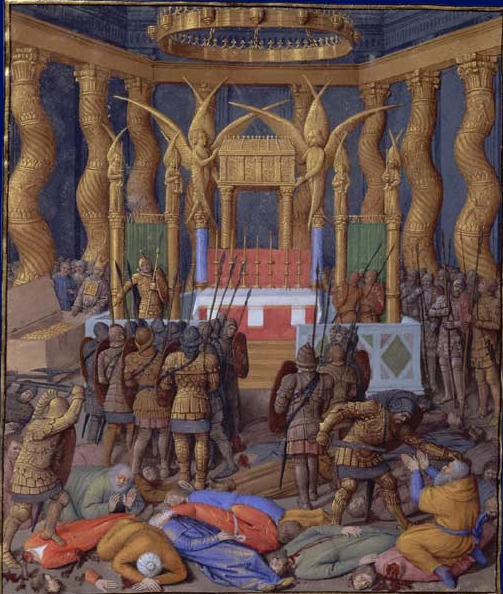

Marching down from Asia Minor, the great general occupied Antioch and proclaimed the incorporation of Syria and Cilicia with the Roman empire. Almost everywhere the change was welcomed as a happy deliverance from anarchy. The cities and dynasts made their submission, and little fighting was needed. A mountain tribe or two had to be chastised, the Arabs were thrust back into their deserts, and a handful of fanatical Jewish patriots, who shut themselves up in the temple of Jerusalem, were beleaguered and annihilated. It was after storming this stronghold that Pompey made his entrance, sword in hand, into the Holy of Holies, and marvelled (as Josephus relates) at the strange sanctuary of the Jews, where a bare room without an image, and now even with out an ark, was set aside for the earthly abode of the invisible God of Zion. The Roman proved a not ungenerous conqueror: but the rabbis of the next generation, and after them many a mediaeval chronicler, loved to tell how he lost his good luck from the moment that he dared to draw aside the curtain and step across the fatal threshold. Hitherto all had gone well with him; from B.C. 63 onwards all was to be disillusion and disappointment.

It was while lying in his camp at Jericho, planning an expedition against the Nabataean Arabs of Petra, that Pompey received the news that Mithradates was dead. The old king had tried too long the patience of his sons and his soldiers. Wearied of his wholesale executions and his wild plans for directing impossible expeditions against Italy, they had risen against him, and he had been forced to save himself from murder by committing suicide. His son and successor, Pharnaces, sent his embalmed body to Pompey, who, shocked at the unfilial act, ordered it to be laid in the family sepulchre of the kings of Pontus at Sinope.

The next year, B.C. 62, when all opposition in the East had been beaten down, was devoted to the delimitation and organisation of the new provinces which Pompey had added to the Empire — Syria, Cilicia, and Bithynia-Pontus. It is universally agreed that the settlement was carried out in a wise, generous, and statesmanlike way. Even Dr. Mommsen acknowledges that “though conducted primarily in the interest of Rome, secondarily in that of the provincials, it was comparatively commendable. The conversion of the chief states into provinces, the better regulation of the eastern frontier, the establishment of a single and a strong government, were full of blessings alike for the rulers and the ruled.” The name of Pompey always remained popular in the East; fifteen years later, when he was engaged in his great civil war with Caesar, he found the Asiatic provinces perfectly loyal, and drew from them his most important resources. His dealings alike with the petty princes and the Hellenized cities were wise and upright. But he set his mark most notably on the land by the great number of towns which he founded or restored. Almost without exception his new colonies proved successful; their sites were well chosen, their constitutions wisely framed; they grew and flourished. Indeed, to Pompey more than to any other single person must the first beginnings of civil life in many parts of Eastern Asia Minor be ascribed; before him towns in the Pontic inland and certain other districts were almost non-existent. Even the places in Cilicia peopled with reclaimed pirates did well. In short, he was in the East almost as great a founder and organiser as Caesar in the West, though his work in this direction has been well-nigh forgotten.

In the winter of 62 Pompey had at last completed his long and laborious task, and set out on his homeward way, bearing his enormous spoils, and with his victorious legions at his back. Of the stir and disquiet that his approach produced we have already written, while dealing with Crassus and Cato; but when the “New Sulla,” as his disloyal critics chose to call him, landed at Brundisium, he showed no intention of marching on the city or starting a proscription; he behaved like a victorious general of the good old days, duly disbanded his soldiery, and came up to Rome unarmed, to receive, as he supposed, the thanks and the credit that were most certainly due to him.

It was an astonishing piece of civic virtue, if we consider the temptations to a man of ambition. If he had chosen to stretch forth his hand and ask for supreme power, it would undoubtedly have been within his grasp. The Democrats were cowed by the failure of the Catilinian conspiracy; the Optimates had no army to oppose to the victorious legions of the East. But the crown and the sceptre were not his desire. He had no notion of upsetting the Republic, in which he only desired to be the first citizen. It is absurd to say with Mommsen that “fortune never did more for any mortal than for Pompey, but on those who lack courage the gods lavish all things in vain.” Is it the duty of every capable man to snatch at a tyranny? And why should Pompey be called a coward for refusing to subvert the immemorial constitution of Rome? He had no political schemes to work out, no great programme of reform to broach. All that he asked was to be the first servant of the state, the man to whom practical tasks of first-rate importance should be assigned in times of difficulty, and who in times of peace should live in dignity and quiet, enjoying the honours that he had earned. He demanded no more at present than the ratification of his arrangement in Asia, and a liberal provision of land or money for his faithful legions.

Expecting to find the people grateful for all his splendid successes in the East, Pompey came confidently before them to give an account of his doings of the last five years. To his surprise, he found that the Roman public was only half-informed as to his achievements, and rather disposed to be indifferent to them. “His first oration,” says Cicero, “promised nothing to the poor; it gave no encouragement to the Democrats; to the wealthy it was unsympathetic; to the Optimates it seemed trivial.” Instead of meeting with a brilliant reception, he was pestered with a hail of questions on domestic politics from the spokesmen of the rival parties in the state. Did he or did he not approve of the execution of the Catilinian conspirators? Was Cicero pater patriae or guilty of judicial murder? Pompey was surprised and gave no certain sound: itaque frigebat, says Cicero — he was coldly received by every one.

The Senate, nevertheless, might have made him their good friend by a little courtesy and encouragement, for he disliked Crassus far more than any of the leaders of the Optimates, and he quite realised the way in which the Democratic party had been worked against him in his absence. Cicero hoped for a time to secure the alliance, but there were insuperable difficulties in the way. In the first place, the orator could not speak for his party or conclude any bargain in its behalf, for the short-sighted oligarchs, whose leader he imagined that he was, declined to follow him. When Lucullus and Cato declared that Pompey was not a safe ally, the majority of the senatorial party trusted them rather than Cicero. They adopted an attitude of covert hostility to the great general, and when the critical day came round, would not vote that his requests should be conceded. If anything more was needed to estrange Pompey from the Optimates it was the personal character of Cicero. The orator wished to be friendly with him; he loved to go about in his company and to hear him called in jest “Gnaeus Cicero;” but this was merely because it gratified his vanity to be able to treat as an equal the man to whom he had once looked up as a leader. The two were not really suited to be friends. Pompey was stolid and solid and wholly uninterested in literature or society ; Cicero was a literary man to the finger tips, with all the self-consciousness and vanity of the “artistic temperament.” It is certain that they bored each other, and that their friendship was a hollow and lukewarm affair.

Pompey might have continued to tolerate Cicero, if the latter had been able to carry out his share in the projected alliance — to induce the Optimate party to grant the ratification of the Asiatic treaties, and the provision of land and money for the disbanded veterans. But this Cicero proved utterly unable to do: meanwhile he irritated his would-be friend by his ludicrous vanity and his oratorical airs and graces. We have already seen, while dealing with the life of Crassus, how he succeeded in offending Pompey by his autolatrous harangues in the Senate, and his frank assumption of equality with his former chief.

As the year B.C. 60 wore on, Pompey came gradually to see that he would never get his very moderate demands conceded by the Senate. His disgust was complete when Cato, at the instigation of Lucullus, proposed, and carried, a motion to the effect that his Asiatic acta should not be ratified, but that the Senate should go through and criticise every treaty and edict that he had made, con firming or rejecting each as it might think proper. The proposal to provide land for the veterans was also taken into consideration, but it came to nothing, on the excuse that the treasury was empty, a manifest evasion, since the enormous Asiatic spoils had been very recently paid into the public chest. When Pompey set up his friend the tribune L. Flavius to propose a plebiscitum giving a competent grant of land to the soldiers, Democrats and Optimates combined against him, and the bill had to be dropped.

It is impossible not to regret the unwisdom of Cicero and the suspicious hostility of Cato, which frustrated the chance that Pompey might settle down once more into an honourable retirement. But his present position was unbearable. Because he had neither armed cohorts at his back, nor bands of hired rioters to sweep the streets, he was impotent. He might still have got what he wanted by raising his hand and bidding his old legions reassemble: forty thousand angry and disappointed men would have rallied around him in a moment. But how ever much provoked, he shrank from open treason and from civil war. Before all things he was a good citizen, and now, as in B.C. 71, he made no unconstitutional move.

But when he received the offer of the Democratic chiefs to do for him what the Senate had refused, and to obtain for him complete legal satisfaction for his desires, he did not now hold back. Caesar had shown his willingness for an alliance by supporting Metellus Nepos in B.C. 62; Crassus also now came forward with proffers of friendship though he had almost fled from before Pompey’s face when first he returned to Italy, and though he had been doing his best to thwart him ever since. Seeing no other way out of his difficulties, the Conqueror of the East reluctantly accepted their advances, and the “First Triumvirate” came into being.

Once before, in B.C. 71, Pompey had leagued himself with his rival; then the alliance had been a passing phase in politics, and no permanent results had followed from it. But the “First Triumvirate” was a very different matter: it was the dominating fact of the next ten years, and marked a new stage in the decadence of the Roman Republic. The state had experienced before the tyrannical domination of a party, under Cinna and Sulla; but the triumvirs were not a party: it would be ridiculous to call their success a triumph of the Democratic faction. They were three men of very different character and aims, who had combined to secure their personal ends, and not to carry out any party programme.

Pompey received all that he had asked in the matter of grants and laws, and was, no doubt, satisfied for the moment; but it must very soon have been borne in upon him that he had now made himself a mere partner in a firm. The days when his personal influence could be exerted for any end that he chose were over: in all his doings he would have for the future to consult his partners. He was no longer responsible to himself only, but had to consider the wishes of Caesar and Crassus.

Meanwhile there was no crisis either at home or abroad which seemed likely to provide work for Pompey. In such times of peace he had been wont to relapse into a dignified retirement till he should again be wanted. This was once more the line that he took in B.C. 59 forgetting that his whole position had now been altered by the fact that he had accepted a place in the triumvirate. It is a different thing to be a general taking holiday on furlough, and to be a sleeping partner in a great firm. The soldier, liable to be called back to the field at any moment, has no responsibilities save to his country, and may do much as he pleases; but the partner who does not take his share in everyday business, and prefers dignity and leisure to the incessant work of supervising details, gradually loses his controlling power. When he does, on occasion, sally forth from his retirement, he finds that he has got out of touch with the affairs of the firm. He may resent the situation, but he will find it difficult to reassert himself.

This is more or less what happened to Pompey during his long alliance with Caesar and Crassus. No sooner had he seen the bills in which he was interested safely passed through the Comitia, than he withdrew for a space into private life. As one of the pledges of the alliance, he had married Julia, the young and charming daughter of Caesar. He retired with her to his Alban villa, seldom came down into Rome, and took no important part in public business. Of his colleagues, Crassus seems to have relapsed once more into his obscure wire-pulling behind the scenes. Caesar had gone off to Gaul, there to build up the army which was one day to make him the master of the world. There was no doubt that the triumvirs could, when they pleased, make their power felt, and do anything that they might choose: but for a space they did not assert themselves, and allowed the local politics of the streets and the Senate-house to drift on in their old fashion. The fact had yet to be realised that those who have taken responsibility upon themselves must interfere in small matters as well as in great, if they wish their power to be remembered and respected. While Pompey lived the life of the Aristotelian megalopsychos and kept aloof from the dirty details of politics, while Crassus jobbed and intrigued, and Caesar slew Germans and Helvetii in Eastern Gaul, the city was disturbed by all manner of unnecessary riots and tumults, the work of that irresponsible and absurd personage, the demagogue Clodius.

Since the downfall of the Concordia Ordinum and the triumph of the triumvirs, the Senate was wholly incapable of keeping order in the streets. On the other hand, the new triple alliance did not choose to undertake the task; indeed, there was no legal machinery by which they could have done so. So while the fortunes of the world were really being settled in Gaul, the city was at the mercy of the noisy young aristocrat who wished to be taken for the heir of the Gracchi and of Saturninus. Clodius was an accurate copy of Caesar, so far as debts, debauchery, and a talent for mob-oratory could go; he called himself the last of the great Democratic tribunes, but he was really nothing more than an exuberant rowdy who loved rioting for rioting’s sake. His only redeeming qualities were a sense of humour and a love of practical jokes. It is impossible to take him seriously; if we did, we should have to denounce him as the worst example of the decadent Roman. He was of no real political importance; his programme was a patchcloth of flimsy odds and ends from the rag-bag of the practically defunct Democratic party. Any one that had the command of half-a-dozen cohorts could have disposed of him in ten minutes: the days were past in which the city mob was a factor of serious importance in Roman politics. But as long as the triumvirs let him alone, he could do much as he pleased in the Forum, and he made himself an intolerable nuisance for seven long years.

The proper way to have dealt with this pestilent fellow would have been to borrow half a legion from Caesar and clear him and his myrmidons out of the city. The Senate could not do this, and Pompey and Crassus would not. At first he had been their tool. When he set up in business for himself, they suffered him for a long time to deal with the Optimates as he chose. Pompey would not even intervene to save Cicero from banishment, in spite of all the orator’s appeals. He considered that he had been badly treated by him in B.C. 60, and was not unwilling that he should have a lesson which would show him the vanity of his belief in his own political importance.

After no very long time of waiting the orator was avenged, for Clodius, intoxicated with his long series of successes in the Forum, took to treating Pompey himself with less respect than was his due. He began with releasing, contrary to the triumvir’s wishes, the captive son of Tigranes, the Armenian king, who was being kept at Rome to prevent him from raising trouble in the East. Then he prosecuted some of Pompey’s dependents, and when their patron came down to give evidence in their behalf, assailed him with ribald insults and set a carefully selected mob to hoot at him. Pompey’s dignity was hurt. He had often been the object of hate and fear in his earlier years, but it was a new thing to be the butt of vulgar jokes — to be called in one breath the tyrant of Rome and “the man who scratches his head with one finger.”

It may be hard to say what is the right course for a respectable politician of first-rate importance to take, when he has been mocked and flouted by a vulgar demagogue. It is clear, however, that Pompey’s reply to Clodius was a hideous mistake. He summoned clients and pugilists about him, and replied by violence to the violence of the tribune. This was undignified, unwise, and unprofitable. It was honouring the rowdy overmuch to copy his methods. But the worst thing of all was that Pompey was not even successful. His bands were amateurs in rioting compared with the partisans of Clodius: they were several times out of the field, and he himself was beleaguered in his house.

This wretched interlude lasted throughout the later months of the tribunate of Clodius, and it was not till he had gone out of office that things righted themselves a little, and Pompey was able to reassert himself. In the next year he took his revenge on the demagogue, by assisting the leading Optimates to recall Cicero from exile, The orator had learnt his lesson, and no longer over-estimated his own power and authority. He never for gave Pompey for having allowed him to be expelled in B.C. 58. However, he was constrained to behave as if gratitude for his tardy return was his only sentiment. Shortly after reaching Rome he is found supporting an important proposal for the creation of a new special com mission for Pompey’s benefit.

Some five years had now passed since the great general had held any office, and he seems to have thought that it was high time that he should again come forward. Some thing must be done to make the Senate and People forget the ignominious contest with Clodius, in which he had cut such a poor figure. No war was raging at the moment, save indeed the Belgic campaign, in which Caesar was winning new laurels; but if Pompey could not ask for military work, there was a tiresome administrative problem on hand, with which he thought himself competent to deal. The year B.C. 57 was a time of dearth and famine all over the Mediterranean lands, and even Rome itself was suffering from scarcity. There was no regular machinery in the constitution for dealing with such troubles, and in earlier years famines had been met by special decrees of the Senate appointing persons to buy corn. At a hint from Pompey, his friends (led by the tribune Messius) brought forward the proposal that a special commissionership should be assigned to him, em powering him not only to deal with the existing dearth, but to reorganise the corn-supply of Italy on a permanent basis. Remembering the times of plenty which had fol lowed on his campaign against the pirates, the people eagerly took up the cry, even though Clodius tried to persuade them that the famine had been brought about by a deliberate “corner in wheat” got up by Pompey’s friends. The accusation was a little too absurd to deceive even the denizens of the Suburra. In spite of the demagogue’s noisy opposition, and the secret intrigues of the irreconcilable Optimates, a commission was granted to Pompey, which gave him charge of the corn-supply for five years, placed a large sum of money at his disposal, and granted him proconsular authority, concurrent with that of the governors, in the provinces. A very unnecessary addition, to the effect that he should also be empowered to raise a war fleet and a land force, if he found it necessary, was rejected. It does not seem that Pompey himself asked for such a grant. It was probably the invention of some of those over-zealous friends with whom most statesmen are cursed.

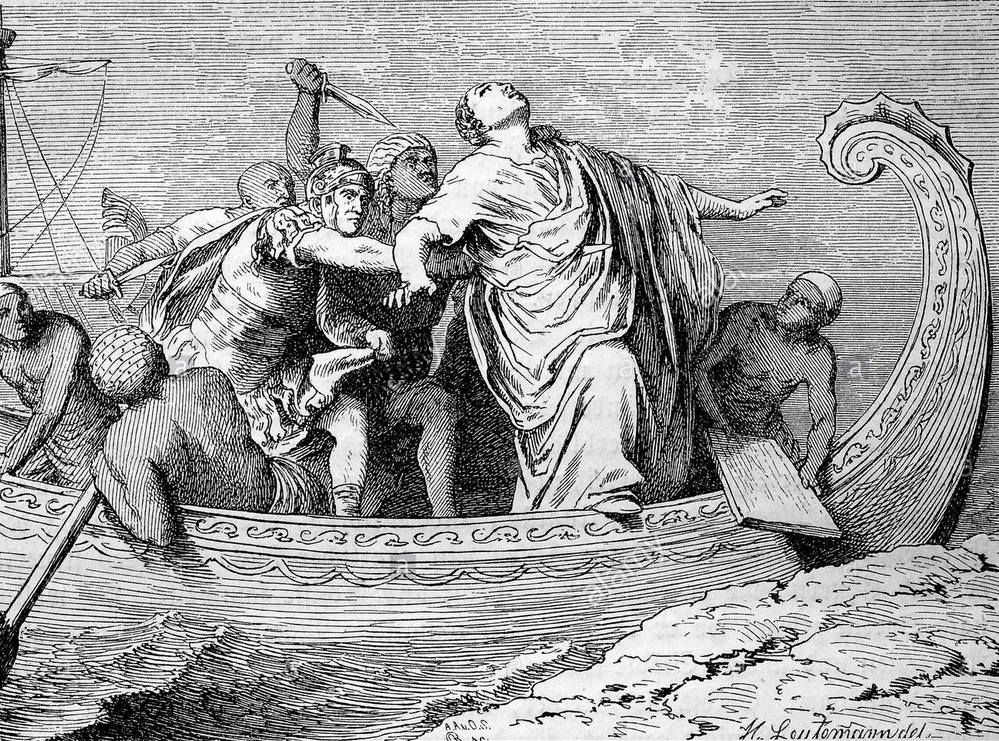

The famine was daily growing worse, and the high commissioner did not delay his departure. He announced that he himself would visit Sicily, Africa, and Sardinia, while his legates should deal with the remoter provinces. He set sail in the midst of a fearful tempest early in November B.C. 57. The captain of his vessel made much ado as to starting, and asked him to wait for a few days till the gale should have blown over. “It is necessary to sail, it is not necessary to live,” replied Pompey, and put to sea in the face of the tempest.

In this commission, as in every other administrative work that he took in hand, Pompey acquitted himself in the most satisfactory way. His winter voyage to Sicily and Africa turned out most prosperously. When he sought for corn he found it: apparently the dearth had been due as much to maladministration by the local governors as to a real shortness of supply. He insisted that, in spite of the season, ships should be sent out at once to carry the grain that he had collected to Italy. “In short, his success was answerable to his energy. He covered the sea with vessels and filled the markets with wheat, insomuch that there was soon an overplus in Rome to feed the provinces, and plenty, as if from a fountain, flowed over the world from the city.” Nor was it only the needs of the moment that were provided for: Pompey made permanent arrangements for the improvement of the corn-supply, which worked perfectly well during the short remainder of the Republican régime.

While he was still absent in Sicily there was a complicated interlude at Rome. The worthless King of Egypt, Ptolemy Auletes, who had just been expelled from his realm by the Alexandrines, came to Italy to ask for help. There was considerable competition among the leading men at Rome for the commission to restore him to his throne, for such jobs were always profitable to the commander to whom they were intrusted. Lentulus Spinther and several others intrigued for the post, and while they were wrangling Pompey’s friends proposed that he should be sent to Egypt as soon as his present task was completed. The Optimates hunted up a Sibylline oracle, to the effect that “the king must not be restored by an army.” But when the news reached Pompey, he sent back a message that he was prepared to restore Ptolemy without asking for a single cohort: it would merely be a matter for negotiations. In accordance with this hint, the tribune Caninius brought forward a bill providing that Pompey should be sent to Alexandria with no more retinue than two lictors, in order to reconcile the king to his subjects. But the Optimates used all their influence against the proposal, employing the hypocritical plea that so valuable a life must not be risked among the turbulent Egyptians. The Caninian bill was rejected, and Ptolemy went back to the East; in the next year he got himself restored by a private bargain with Gabinius, the proconsul of Syria — a simpler if not a cheaper method than that of making a formal appeal to the Senate and People.

In spite of the fact that he had stopped the famine, Pompey found that he was in a more unenviable position than ever when he returned to Rome. The Optimates, elated by the rejection of the Caninian bill, raised their heads and dared openly to oppose him: Clodius began once more to make him the mark of the foulest abuse and to raise mobs against him: Crassus, in spite of the fact that the alliance of B.C. 60 was still ostensibly in existence, intrigued against him, and even (so Pompey complained) became privy to a plot for his assassination. So helpless did he feel, that he resolved at last to appeal to Caesar, the one man who was able, if he chose, both to make Clodius keep silence and to frighten the Optimates. This must have been a bitter humiliation to him; he had to confess that he had proved totally unable to manage domestic affairs, and to ask for the second time for his father-in-law’s help. Caesar was now a very different personage from the mere Democratic politician of B.C. 59. His Helvetian, German, and Belgic campaigns had raised him to the highest rank as a general, and he already had a numerous and devoted army at his back. Pompey must have felt that their relative importance was much changed since they had last met each other on the eve of Caesar’s departure for Gaul. Then he had been Rome’s only general, and his colleague a clever demagogue with a doubtful past : now he was a notorious political failure and Caesar the idol of the soldiery. But the Gallic wars were only half over, and it is probable that the elder man did not even yet realise his ally’s full genius. It was to Caesar, the manager of Rome’s politics, not to Caesar, the master of many legions, that he was appealing.

Pompey’s visit to his father-in-law’s province was made in the guise of a mere side-excursion. While purporting to be on his way to Corsica and Sardinia, to reorganise the corn-supply, he turned aside to Lucca, where Caesar had fixed his quarters for the winter of B.C. 57-56. He was not the only visitor whom the proconsul of Gaul had received. Crassus had been with Caesar at Ravenna a few weeks before, bent on the opposite design. He thought that he at last saw his opportunity for edging Pompey entirely out of his political position. If Caesar refused him help, he would sink into insignificance, and become a mere negligible quantity. But it was not the intention of the conqueror of Gaul to break with either of his colleagues. He preferred that during his absence there should be a balance of power at Rome. It would not suit him that either Pompey or Crassus should be reduced to impotence ; still less was it his game that the Optimates should be allowed to seize the reins of power. The more distracted were home politics, the more important would be his own position. Some day he would come back to Rome to work his will; and when that day should come, he would prefer to find the city masterless and ill-governed. Meanwhile, there was still much work to be done in Gaul; the province was but half subdued, and his own army was not as yet so large or so devoted to himself as he hoped to make it.

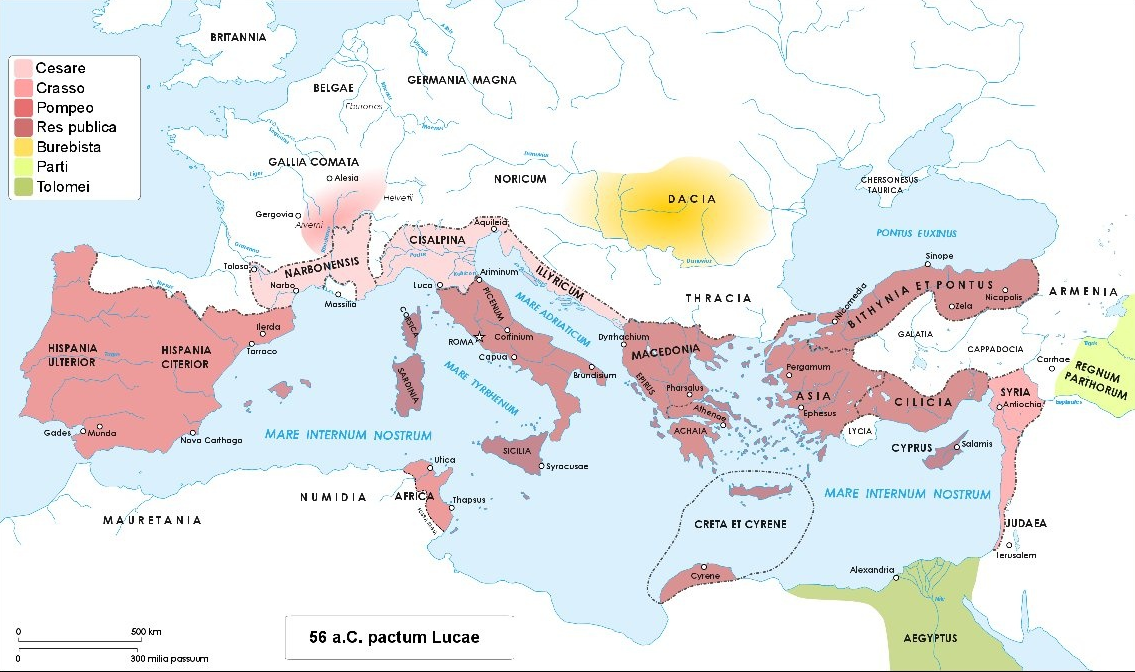

Hence it came to pass that the conference at Lucca ended in a way that must have been unexpected to many of the onlookers. Caesar insisted that Pompey and Crassus should both remain his allies, and once more (as in B.C. 70) they went through a solemn farce of reconciliation, and professed to put away their old quarrels. The next step was to draw up the political programme for the ensuing year. Caesar claimed nothing more for himself than the renewal of his proconsulship in Gaul for another five years, and the right to raise more legions. In return for this concession he undertook not only to get Pompey and Crassus made consuls for B.C. 55, but to allow each of them to take a province and an army when their year of consulship should have expired. Pompey was to receive Spain, Crassus Syria. These were astoundingly liberal terms! Caesar seemed to be arming his colleagues against himself, and to be making them the present of a position which they could not have obtained by their own exertions. For it was he, and not they, who managed the whole business; he had but to give the signal and pull the wires, and immediately Clodius relapsed into silence, and the Optimates drew in their horns and stood still. It is not till we mark the consequences of the conference of Lucca that we realise how predominant was the position that Caesar had already acquired. To his ancient power of intrigue and mob-management he now added the command of an ample provincial treasury and a large army. Absent though he was from Rome, he could secure that his desires should be carried out. If he now assigned provinces and legions to his confederates, it was because he knew their characters well, and did not fear them. They would always be at secret enmity with each other, and would practically cancel each other as factors in the political situation. Meanwhile they would, as he calculated, keep the Optimates quiet; each of them had suffered too much from the senatorial party to be willing to conclude an alliance with it.

In making this political forecast Caesar committed an error. Pompey and Crassus duly received their consulships and provinces, and the Optimates were duly repressed. Cicero, as their representative, was forced to make that apology for his late attempts to kick against the triumvirs which he called his “recantation” [palinodia]. So far things went well for Caesar, but he had not allowed for two possibilities. The first was the death of Crassus, who lost his life and his army at Carrhae in B.C. 53. By his removal from the scene the counterweight which kept Pompey in check ceased to exist. The second factor in the new situation was the growth of an overmastering jealousy in Pompey’s mind, which led him into paths where it had seemed unlikely that he would ever stray. The elder general did not want to be king or dictator of Rome; this he had proved half-a-dozen times already. But he was also entirely resolved that no one else should aspire to such a position, and month by month it grew more clear that Caesar might do so. This Pompey was determined to prevent; he had given himself a colleague, but he did not intend that his colleague should become his master. Such was the secret at the bottom of that gradual estrangement between the two men which grew more and more evident as the years B.C. 53-50 rolled on. Both morally and legally Pompey’s suspicions of Caesar were entirely justifiable. But unfortunately he had placed himself under great obligations to his colleague; his conduct was bound to wear an invidious aspect when he began first to take measures of precaution against the man who had helped him out of his difficulties, and then openly to oppose him. Of this he was himself well aware; it was the main reason for his long hesitation and hanging back, before he finally declared himself the foe of his benefactor. When Cato, not long before hostilities commenced, taunted him with having allowed Caesar to grow to his present greatness unopposed, Pompey replied that the man had been his friend and his father-in-law.

Those who, with Mommsen, attribute to Pompey nothing but the meanest impulses, call personal jealousy alone the cause of his breach with Caesar. And that feeling was undoubtedly a powerful element among the mixed motives which swayed his mind ; but there was something more: there was the honest political conviction that Rome did not want a despot. He himself, whose opportunities in the past had been so great, had not chosen to be king; why should another be allowed to snatch at the crown? The literary partisans of Caesar justify their hero by replying that he turned out to be a heaven-sent saviour of society. But even granting that this is true, how could any Roman of B.C. 51 have known it? Caesar was naturally judged by his dubious past, not by the glorious present in Gaul; his future no man could have foreseen.