Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Shots Fired in Anger: A Rifleman’s-Eye View of the Activities on the Island of Guadalcanal, by Lt. Col. John B. George (published 1947).

Japanese Rifles: The Arisaka 6.5mm

Japanese rifles used in World War II were all copied from the basic Mauser pattern, and as in the case of other nations’ modifications of Paul Mauser’s good rifle, most of the changes proved to be steps backward. They retained to the last the straight bolt of the old 98 Mauser, made quite a few minor changes in the ignition assembly, adopted a different floor plate latch, and extended the tang portions of both receiver and guard to facilitate the use of a laminated buttstock. It would have been a more practical procedure to have simply tooled up for the Model 98, as was. The Japs simply joined what might well be called an international association of fumblers, who, faced with a near-perfect model to work from which they were absolutely unable to improve, went ahead nevertheless and worked a few of their own ideas, producing their so-called “version” of the good old German man and game killer; and like our own Ordnance Department, they produced a bastard rifle.

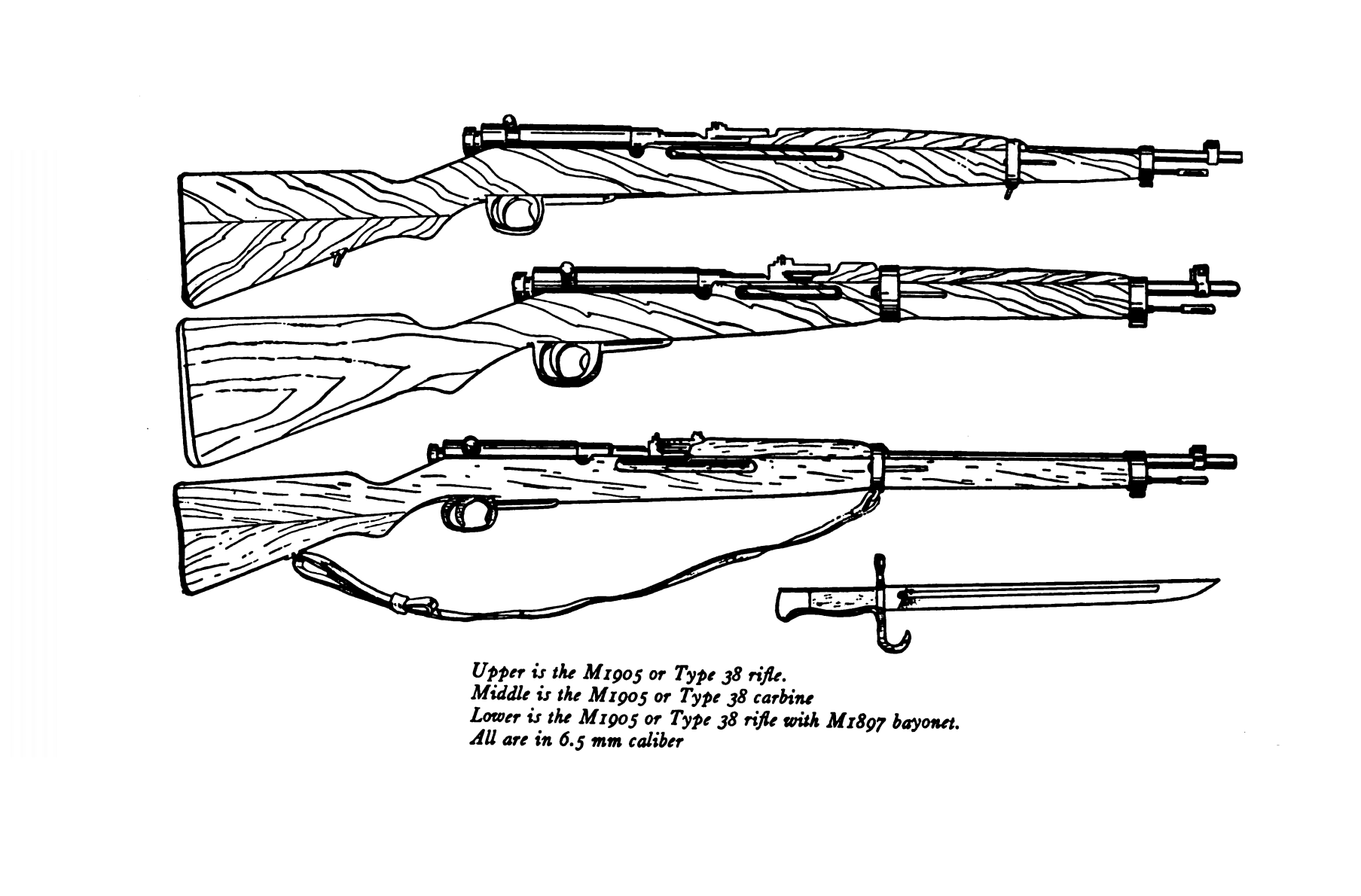

For one thing, they made their rifles entirely too long. The standard Model 38 6.5mm, for instance, had a ridiculous thirty-one and a quarter inches of barrel screwed into it, which gave the weapon an overall length of fifty and a quarter inches. The only worthwhile purpose served by making the barrels that long was a great reduction of muzzle blast and flash — which furnished the American uninformed (including one high ranking general) with reasons for stating erroneously that the Japs had developed an absolutely smokeless powder, much better for jungle fighting than any of ours.

There were, of course, numerous disadvantages to the longer rifles. They were unwieldy and awkward, especially in the jungle. They were too heavy for their caliber. And this excess of weight and length, unlike certain other features built into Jap rifles, was certainly not demanded by any of the peculiarities of the Jap soldier. The Jap doughboy was an awfully little man, on the average, for such a big gun.

Another fixed idiocy of the Japs was manifest in the adoption of the receiver cover for all rifles. Its utilization necessitated the cutting of two deep grooves for almost the full length of the receiver, which certainly did nothing to strengthen the action. The protection which that foolish contrivance could give to the working parts of the rifle was negligible, and if it was kept on during temperature changes — such as those incurred in transferring the weapon from the shade into the sunlight — it worked to facilitate the condensation of moisture and the resultant formation of big gobs of rust on the bolt surface and ignition parts. Whenever the action was operated with the receiver cover on the weapon rattled like all of the proverbial tin pots and pans in hell. I know of at least two Japs who were located by our people because of that rattling sound as they operated their bolts, and who were killed before they fired a second shot.

The Jap-instigated alterations of the ignition mechanism tended to increase the weight of the moving parts over those of the Mauser. A hollow firing pin and upper sear engagement such as the Japs developed must have been rather difficult to manufacture — even if it did eliminate the need of the Mauser-type locking arrangement of upper sear engagement and firing rod. It is nice to aim this criticism from an entrenched position. Standing in my own shoes I can criticize the Japs for the changes they wrought in the Mauser firing pin mechanism, but if I happened to be one of the “experts” who developed the action of our own M1903 modification of the Mauser, I would keep awfully quiet about the whole thing. Because compared to the ill-conceived ignition system of our own bolt action, which was designed with no regard whatsoever for the basic principle of firearms design which demands a firm, crisp blow on the primer, the Japanese modification is a dream of perfection. When our own experts chopped the sturdy one-piece Mauser firing pin in two, and then coupled the two poor dismembered parts together for operation with an inherently ill- functioning joint, they succeeded in accomplishing at one stroke of the drawing pen a point of extreme unreliability for the Springfield rifle, and they also made certain that there was at least one part of their rifle that would break with great regularity, causing the target shot to have to fire many alibi runs on the rifle range — and making the soldier do God knows what on the battlefield. The United States and the Japs alike, in my opinion, would have done well to have adopted the Mauser ignition system as it was.

The Japanese extended their dirty work farther back on the bolt and produced a safety and lock that, though mechanically sound, was vastly inferior to the one on the Mauser, being equally difficult to manipulate with cold fingers, and generally more noisy in operation. Its flaring rear, mushrooming outward on the end of the bolt, did provide some protection from the escaping gases which naturally accompanied the use of poorly loaded Japanese ammunition, and its secureness against allowing bolt parts to be blown rearward into the firer’s face was likely greater than the Springfield.

The Japs, like many of our experts, were still living in the dark ages when it came to weapons-sense, and were similarly overly bayonet conscious, going to great lengths to make their rifles into good bayonet handles. They built massive upper bands and hooked good strong studs onto them and kept the front sights and the muzzle ends well adapted to the fitting of these long-obsolete toad stabbers. And they accordingly increased the weight of all of their rifles. The folding bayonet on their Model 1911 6.5 Cavalry carbine with its massive hinge and latch provided the high mark of this foolish and barbaric influence in modern weapons design.

In case the foregoing paragraph has not made my stand in this matter clear, let me give you my own opinion on the bayonet and hand-to-hand combat in general. It is my belief that the bayonet is about as useless a bit of equipment in this present day and age as the cavalry saber. We should have dispensed years ago with both the weapon itself and the hours of wasted effort which went into bayonet instruction. The present-day apologists for the retention of that obsolete item will argue for the first few minutes of a discussion and claim an actual combat value for the weapon; then, when loudly called down and corrected by all of the men in the room who happen to be wearing Combat Infantry Badges, they will lapse into a lot of drivel about “stimulating morale” and “improving the physical condition of the soldier.”

Such arguments are as stupid as they are dangerous. There are plenty of the useful phases of training which will serve to teach a useful subject to a man and harden him physically at the same time. And if you want to give a man calisthenics — well, give him calisthenics. Don’t try to sell an intelligent American on the idea of killing his enemy the way Sir Galahad did. Let the foreign nations retain their ideas about bayonet fighting. After our experience in this war, we can rely on our own judgment — at least in the evaluation of foreign methods.

For all practical purposes, there hasn’t been any bayonet fighting in this war of ours — and it is time we admitted our past foolishness in hanging on to the bayonet all of these years. It will be even more foolish for us to continue to weigh down the front end of our weapons with a lot of extraneous wood and metal in front of the lower band.

(We are not now making that mistake, for the bayonet has been cut to knife length — and is mainly being used as a knife. It was to our advantage that the Japs wasted much more time and effort than we did with pig-stickers. It is to the great discredit of our intelligence that we waited so long to change our bayonet into a sheath knife that would be put on the end of a rifle for morale and other purposes.)

In addition to the features of the Jap weapons which were more or less arbitrarily decided upon by Japanese ordnance authorities, there were a number of points which were more or less demanded by the fact that the Jap soldiers were, on the whole, mechanically stupid. Jap weapons design had to be influenced by the faults of the Jap soldier.

I refer in particular to the barleycorn front sight and the open V rear, which are the simplest, the most rugged, and the most practical sights for the use of men of peasant background and I.Q. After a great amount of personal experience gained in instructing the Chinese, that fact has at last become obvious to me. The great problem faced by the Jap marksmanship instructors was more mechanical than visual. They had to get across the idea of trigger squeeze, so that the canny Jap would not tend to buck his shot two paddy fields to the right of his target. Those people weren’t worried about making their man able to put all of his shots into a ten-inch bull at two hundred yards — they were worried about enabling him to stand some chance of hitting a man standing up at a hundred. (We could have done well at some of our IRTC’s to have reoriented our own training program in that same direction.) The barleycorn sight, age old, familiar, simple as hell, made just as good a sight as any for the mine-run Jap doughboy. Anyone who has faced the abysmal ignorance of the common Oriental soldiers, as I have, will readily back me up in this.

The Japs were more or less forced to use open sights because there were no good military peep sights for them to copy at the time they designed their rifles. The first peep sight which was optically worth a damn was put on the Enfield and the Browning Auto rifles in 1917, and it was a mechanical abortion of the first water. The first practical aperture rear sight which has gotten into popular military use can presently be seen on our own M1. Before its advent, there just wasn’t a good all around peep sight. So, with the exception of a few peep type drift slides seen on an occasional Arisaka, the Japs stuck to the V-notch.

Now, before all of the snipers of World War I jump up and cry for my blood because of my inference that the ’03 Springfield sight is no damned good, let me do a little explaining. It took a highly skilled marksman to use the too-far-forward and entirely-too-small aperture that was on the ’03. The common soldier didn’t fool with it in combat, any more than he did with the sling. And there weren’t enough good shots in either one of our recent wars to cut any ice at all. If, at the outset of this war, we had not had available the excellent M1 rear sight and the properly positioned aperture rear sights which were built into some of the wartime versions of the ’03, I, for my part, would have preferred to see barleycorn-type sights in use on our rifles in preference to the old ’03 sight. Not for my own personal use, mind you, but for the use of the great mass of men who had to be taught to use their weapons in precious few hours time, with a definite limit set upon the amount of marksmanship training of all sorts to be given them. The Japs, at least, recognized one or two of their limitations. If our Garand had been out in time for them to copy it (by 1900 or thereabouts), it might have been a different story — not the war, for it would have taken more than a good rear sight to have changed that — but the Jap that missed my ear a few inches at Morovovo might have hit me in the bean, and that, I think, would have made a big difference, to George at least.

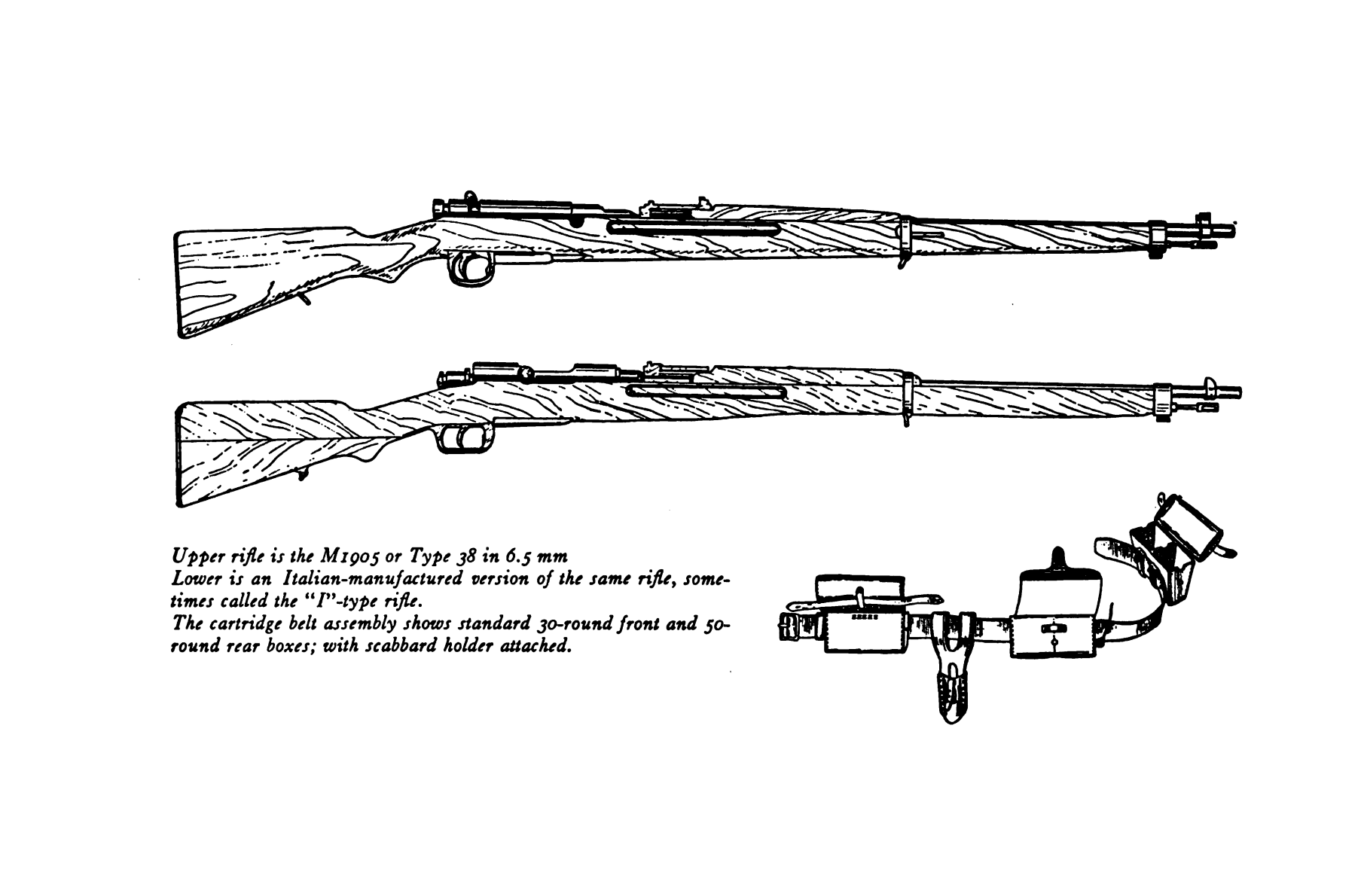

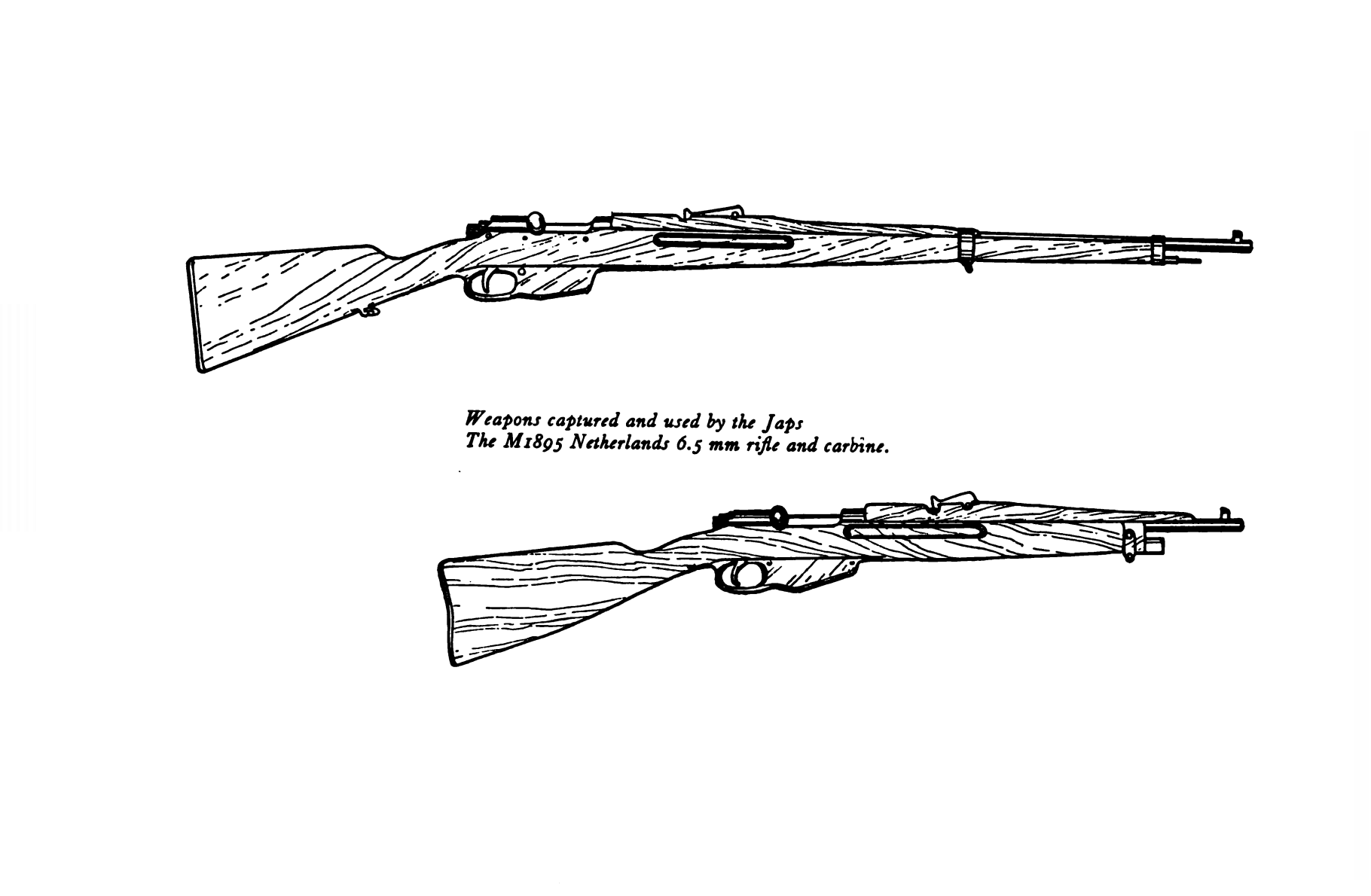

The great mass of rifles which I have so far seen in the hands of Japs has been almost entirely made up of the types commonly referred to as the Arisaka rifles. These are all of the various models officially adopted, which are normally issued to the Japanese Infantry. The great variety of rifles that were seen on every Jap front was present because of the Jap’s great hesitancy to discard anything he had captured, regardless of its uselessness or the unavailability of ammunition. Then too, the Japs frequently captured certain models of rifles and machine guns in such quantities that they thought it wise to load ammunition in their own factories to fit the captured weapons. So, we found large numbers of British Enfields, Dutch Steyrs, American M1917 Enfields, Mausers and Krags in the possession of the Japs on Guadalcanal, with ample evidence that their use was not the idea of individuals, but rather the carrying out of a directive from higher authority. The M1917 Enfields I saw had been modified a bit to take the Jap bayonet, and quantities of Japanese-loaded ammunition were on hand in .303 British caliber for use in the captured British weapons.

There were, of course, far more Japanese than captured weapon around, the long-barrelled Arisaka .25 being seen most often.

The Japanese Model 38 6.5mm Rifle (which is the official name for the standard length .25 Arisaka) is not a bad gun, in spite of the things you have read elsewhere and the derogatory remarks I have just finished making about it. With the exception of the innovation of a hollow firing pin with an inside mainspring, a combination bolt head and safety lock, and the addition of a third lug, the bolt itself is rigidly held to Mauser pattern.

This additional duo-functional lug on the forward part of the bolt which follows the left lug race, is slightly to the rear of the left lug proper, and acts as a bolt stop, thereby saving the important rear surface of the lug itself from being battered, during manipulation, by the bolt stop. This feature, combined with a rearward lengthening of the receiver, acts to prevent the cramping of the bolt in rearmost position. This benefit is secured through firm support of the bolt in its rearmost position where it retains more than two full inches of its length within the receiver barrel. This is an improvement over the Mauser, but it is gained at some cost, for it tends to increase the overall length of the receiver for a particular cartridge.

The extractor is of conventional Mauser design, attached to the bolt by means of the usual collar, and riding in the right lug race. The bolt handle is projected straight outward from the bolt in a direction at right angles to the axis of the locking lugs and is positioned three-quarters to the rear on the length of the bolt. It is some two-and-a-quarter inches in length; and its knob is elliptical in cross section, and its base is square, forming a substantial safety lug. The rifle I have present at hand has a single, large gasport cut through the left side (closed position) of the bolt just forward of the extractor collar. But there were varied types of gasports in other Arisaka bolts which I have seen.

The Arisaka bolt can be disassembled faster than any others of the Mauser type; a rank amateur can jerk it into its five basic units in four seconds and keep a hand free to toy with his gal’s ear all the while, if she happens to be close by.

There is nothing wrong with this bolt except the rather glaring fault of a straight bolt handle. Except for that major shortcoming it would seem to me that the Japs actually committed less non-constructive butchery on the Mauser than did the designers of the ’03 rifle. The guts of the bolt are certainly more foolproof than the unnecessarily complex ’03 arrangement of striker, collar, firing pin rod, and spring; and I don’t think there would have been as much field breakage with the Arisaka if the Japs had used metals equal to ours in their weapons.

The receiver itself follows the old Mauser design with the most apparent alteration being an extension of the tang strip to the rear, for an inch or so. This is mainly for the purpose of facilitating the joining of the two pieces of wood which make up the buttstock of the Arisaka and to provide bedding necessary with the usage of such soft gunstock woods. I doubt if there are any other reasons of importance. The guard, of course, is similarly extended on the under side of the grip and the two are joined at the rear by an extra guard screw set into the rear of the receiver tang through both pieces of steel so that the wood joint is gripped tightly be tween the guard rear and the receiver tang. The bottom cut for the sear is positioned much farther forward in the receiver than on the Mauser, and the engagement is forward, within the rear receiver ring. This position is necessary because of the deeply (forward) cut stroke-space in the rear of the bolt, which allows the use of a relatively short firing pin with its full length retained, at cock or relaxed, within the actual body of the bolt proper. The action does not have a bolt sleeve, its functions being taken over by the rear of the bolt and the safety lock assembly.

The bolt stop and ejector assembly is a clever gadget. It is similar to the Mauser in appearance but a little different in function. The bolt stop acts as does the stop of the Mauser, though it butts against the third lug on the bolt instead of the usual left locking lug. The cleverness of the assembly shows up when we examine the ejector. It is of the pivoting type, similar in principle but not in appearance to the Springfield, and much stronger and more certain. It does not depend upon the continuously maintained pressure of an ejector spring as does the Mauser; nor upon the short radiused and critically timed pivoting action which is used in the Springfield. The Arisaka has instead a long-radius pivoting type ejector which is actuated by the third lug (“bolt stop lug”) as the bolt approaches its rearmost position during the back stroke. There can be no failure due to a clogged or tired spring, which frequently causes trouble in the Mauser, and it is not unduly delicate of construction or critical of fit as is the ejector of ye good old Springfield. The size of the ejector and bolt stop assembly was increased over the copied Mauser in order to gain the advantage described above and, it would seem, the advantage was sufficient to warrant the additional weight and bulk.

The trigger mechanism is roughly similar to that of the Mauser, producing the orthodox military type trigger pull, with a preliminary take up before the full resistance of the engaged sear is felt by the trigger. The trigger looks to be positioned in a much more forward position than the Mauser — an appearance created by the increased length of the Arisaka receiver and the forward position of the Arisaka sear.

The receiver ring is not enlarged to exceed the diameter of the receiver proper and it has two holes in its top, drilled concentrically through the ring. These are presumably gasports; I have seen a few rifles that did not have any, and some which had one such hole.

Throughout my description of the receiver, I have been unconsciously avoiding mention of the useless metal cover which I spoke of earlier in the text. Its stupidity of design is too obvious to merit more than a mere speaking of, and the two unsightly grooves which are cut lengthwise along the receiver to guide the contraption back and forth and keep it in place as the bolt is operated are even worse. The guy that thought that abortion up did dirt to the Jap soldier. Most of the Japs on Guadalcanal were smart enough to throw away this bolt cover and use the rifle with the unblued bolt flashing boldly forth in the sunlight.

The barrels are — in wise retention of the Mauser design — fitted and cut for the extractor in such a way as to give the greatest possible support to the cartridge case. The entire cartridge, head of case and all, enters into the chamber of the rifle, as does the head of the bolt, and the breech closure is the most complete of any modern bolt action rifle in existence today.

The follower is a metal stamped adaptation of the Mauser and the follower spring is a wire substitute for the flat strip equivalent in the Mauser and Springfield. The floorplate is essentially the same as the Springfield, as is the entire guard, though the latch is a modified one of simple lever design to replace the hidden Mauser type. Also, the guard is extended rearward to match the metal of the receiver tang above and to furnish a rearward location for a third guard screw — an artifice meant to hold together the two- piece buttstock. There is ample room in the trigger guard for a heavily gloved finger, though it is not as large as the standard military Mauser’s. The possibility of releasing the floorplate latch with the trigger finger during firing is only theoretical, the latch spring being powerful enough to insure against such mishap.

The profile of the Arisaka’s 31.4 inch barrel is not shaped for accuracy, being bottlenecked abruptly from a point about 1 1/2 inches in front of the receiver. The barrel from that point forward is rather small in diameter, tapering only slightly outward to the muzzle. The rear sight, of the long, folding leaf design, is mounted on a base fixed to the barrel, after the manner of the Springfield, but a little farther forward, with the rear end of its fixed base jutting against a shoulder in the bottleneck of the barrel instead of the receiver itself. The tall, roughly graduated leaf swings upward from the front from a folded-down carry position, pivoting on a pin-type hinge similar to the one on the ’03. It is graduated up to 2,400 meters in increments of 100 meters each, starting with 500, and is scored on the side with a notch for each graduation. The battle leaf is presumably set at 500 and the bottom of the leaf has a notch cut in it to provide a 400 meter setting. These sights are obviously crude and unscientific, but nevertheless highly suitable for the Oriental soldiers to use. The open V notch, which is the only rear sight profile used (there are three separate Vs cut into the rear sight leaf and slide assembly) is matched up with a barleycorn-type, sharp-pointed front sight. The forward position of the rear sight, several inches in front of the Springfield’s, is less critical of focus and has the desirable effect of sharpening up the definition of the rear sight for older eyes — a feature that becomes more desirable when barleycorn and open V sights are used.

Adjustments (for elevation only) are made in the rear sight by pressing a latch on the right side of the elevating slide and moving the slide freely to the desired elevation, where the latch, when released, will take hold in the proper notch on the right side of the rear sight leaf. There is no ready provision for lateral adjustment or windage, although the front sight blade can be driven over to obtain a mean zero. An allowance for bullet drift is not provided for in the design of the rear sight, and in view of the myriad in exactitudes inherent in the barleycorn-type of sights and Japanese marksmanship alike, we can certainly excuse the Jap ordnance experts for skipping over the relatively unimportant factor of drift allowances. This neglect, however, provides proof that in spite of the 2,400 meter rear sight leaf, there was no intent to build a weapon suitable for ultra long range fire at individual targets.

The sling swivels are widely separated on the rifle to make it easy for the rifleman to carry the weapon diagonally across his back and yet keep both hands free for climbing or carrying. The sturdy lower band, which carries the upper sling swivel, is set far out on the forearm of the stock, much too far to permit any use of the sling for shooting purposes, unless the sling might possibly be used in connection with the legs in the Continental back position. The lower sling swivel was almost identical with that of the Springfield, but situated much closer to the grip. In some rifles I saw the lower band was cleverly bedded-down upon a steel fixture neatly fitted into the forearm; this prevented bending the long barrel. The handguard was “packed” against the barrel here with a pad of thin greased cloth.

The stock and handguard, along with the excessively massive buttplate and sling swivels, were obviously constructed with the constant thought of bayonet employment in mind, and they were much stronger than would have ordinarily been necessary for such a light calibered rifle. However, some of that appearance of undue thickness was brought about by the required usage of third-rate wood of which the stocks were made.

The upper band was also heavily built and rather tightly fit about the barrel. The bayonet stud was an integral part of it, cut out of the same piece of metal and placed in the same position as the Springfield or Mauser. A good, steel cleaning rod projected outward from a hole in the forend inside the upper band and was held securely in place by a spring loaded latch inletted into the forend at six o’clock, just to the rear of the upper band. The slings furnished with the rifle, as seen on Guadalcanal, were mostly of good leather, though a few rubberized canvas ones had begun to come through by that time. Later on, in Burma, the Japs seemed to have run entirely out of leather.

The accepted Jap method of firing this long rifle from the prone position seemed to call for gripping the forearm just in front of the trigger guard and lying at the usual twenty-five degree angle from the line of fire while aiming. This put the left forearm nearly vertical, which has its advantages (when not using the sling) with a hell of a lot of long barrel quivering out in front. It could not have been an especially steady position. The more deadly Jap shots, of whom I have encountered a few, were past masters at the improvisation of different forearm rests, which enabled them to fire with greatly increased accuracy. There were not so many Dead-Eye-Dicks to be found, thank God. It doesn’t take very many to be too many and much of the respect which I now have for the deadly effectiveness of rifle sniping is based upon later experiences which, though few in number, drove home in my mind a first hand knowledge of the terror-instilling damage to individual and unit morale which can be meted out by a few accurately aimed rifle shots.

The Arisaka rifle I have just described is a pretty good gun. It is clumsier than any of ours, but in slow fire it is easier to shoot. It has practically no recoil, what with its lengthy barrel, its moderately loaded cartridge, and its weight of ten pounds with sling. It has fair accuracy up to about 500 yards and a muzzle velocity of 2,400 foot seconds, which puts it up in the high power military class and gives it a maximum range of some 2,600 yards. It loads and operates in the same manner as any Mauser type rifle, and although it would not show up as well as the ’03 (or, of course, the Garand) on the rifle range, especially in rapid fire, it would not be much slower to operate and reload under combat conditions.

All of the other rifles I will describe in following chapters have evolved themselves from, or were forerunners of, this basic rifle of the Japanese Army. It was, I believe, the most extensively used Jap weapon in World War II and although it was superseded by later models of different caliber it remained popular with the troops. All of the Japs I have talked to expressed a marked preference for the old reliable Arisaka 6.5 over any of the later Jap guns and all of the foreign guns — except for the Garand. In spite of all of its shortcomings, some of which were so stupid that they defied belief (almost as much as certain of our own ordnance inanities concerned with the adoption of our Springfield) it proved to be a good, reliable combat rifle. And it killed many thousand Americans who were armed with the best weapons in the world.

(Continue to Part 2)

5