Editor’s note: The following sermon was preached in the Congregational Church, Auburndale, Massachusetts, by the Rev. Calvin Cutler on December 23, 1894.

Editor’s note: The following sermon was preached in the Congregational Church, Auburndale, Massachusetts, by the Rev. Calvin Cutler on December 23, 1894.

Luke 2:7. — “There was no room for them in the inn.”

Many a good story will not bear to be told but once. A twice-told tale is tiresome, but not always. There are some old stories so nearly forgotten that they seem to be fresh. There are some old stories that are actually new to each new generation, and of whose real interest thousands of young hearts receive their first vivid impressions from what is said or done at such a time as this. There are some old stories, too, of which even those who hold them in fondest and most familiar recollection never grow weary, and the appetite for which by many repetitions can never be sated nor even satisfied.

Such is the story that is told when Christmas comes. Far as the east is from the west, and almost from pole to pole, is heard the voice of praise for the coming of Christ into the world, as if in answer to the ancient call, “Is any merry? Let him sing.”

It is joy to think how many young hearts are made glad at this season of the year, how many a load of care is lifted off even for a little time, how many a heart that was sinking has been kept up by the sudden conviction, “Somebody cares for me.” And all for Christmas, and Christmas for Christ — and Christ for the world! To many a man bound to business, — like Peter in prison, — when Christmas comes, the chains fall off, the iron gate opens of its own accord, and again in the house, at the sound of his welcome voice, Rhoda loses her wits for gladness.

We hear of the Savior so much in the dark things of life that we are in danger of thinking that the darkness is due to him. We need to see him in that which is bright. He came to bring not darkness, but light; not sorrow, but gladness. The angel had it right: “good tidings,” “great joy,” “to all the people.”

The observance of Christmas is not expressly commanded in the Bible, yet it is a sweet and tender festival to keep our hearts and homes and churches pure. It is in us, when Christian hearts all round the earth are turning to one place, that we should say one to another, “Let us now go even unto Bethlehem and see this thing which is come to pass, which the Lord hath make known unto us.”

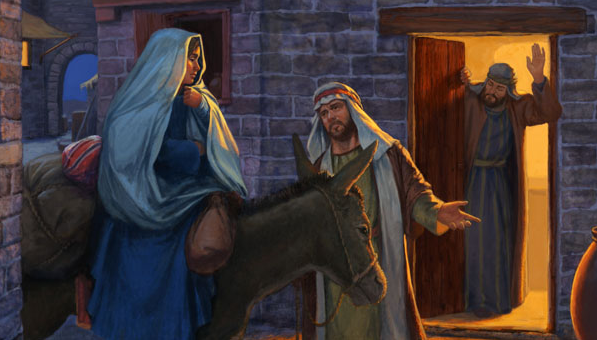

The story, like the festival, is for all the family, especially the children. We will look now at one of the pictures. We see a starry night with one Star conspicuous, a little village on a hill, — a building for travelers to lodge in,— a tired-looking man and woman turning away disappointed, and, underneath, these words written: “No room for them in the inn.” We know who they were,— Joseph and Mary. We know about the inn, how they wished to get lodgings there, and it was full, and how they happened to come at such a time. It was night, and they had nowhere else to stay, and so they had to take to the stable. According to an old tradition, the stable was a cave. There the Lord of all was born, and laid in a manger, the crib where the food was placed for the cattle. And the cattle, as if with friendly eyes seeing what manner of child it was, did not hurt nor destroy him. It makes us think of that Scripture, “The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib.” “There the mother laid her child in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.”

“No peaceful home upon his cradle smiled,

Guests rudely went and came where slept the royal child.”

We think we would like to know the names of those that stayed in the inn that night. What sort of beings could they be? Were they bears? If not, why did they not get up, some of them, and give up their room to these persons? If, afterward, any of them ever became believers, it must have mortified them to think how they were having a good night’s rest, and letting this young mother stay out in a stable, and leaving the child, who was to give his life for them, to be laid in a manger.

Such a thing now would give a bad name to a man or a tavern or a town. It would be notorious as the place where they had no mercy on a little infant and its mother. If in our neighborhood a mother and child were so badly off, some place would be found for them better than a stable. Some kind-hearted neighbor would look after them, or some officer would see that they were cared for, or they would be taken to the hospital. But at that time such a thing as a hospital had not been heard of. That little child brought into the world the spirit that led to the building of hospitals.

It would be thought a mean thing now to treat a woman as the mother of Jesus was treated that night. In such a case there would be many who would exclaim: “No room? They may have my room.” Respect for woman would do as much as that. But this spirit of respect for woman, now so common, was not known when Christ was born.

The noblest product of the Middle Ages was chivalry, and that was due to nothing else but the spirit of Christ. Its dashing courage, to be sure, was an element of the times: but its peculiar excellence, — the taking up the cause of the weak, the wronged, the unprotected,— this had its origin in that lowly birth in Bethlehem, in that child whose mother “laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.”

It was too bad. However, bad as it was, the Savior never laid it up against them. He did not say: “I will treat them as they treated me. When they come to me in their trouble, I will remind them of that night in Bethlehem, and tell them there is no room for them in my Father’s house — none for their children.”

Nothing of that spirit was in him; but he said, “Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbid them not.” The thought of that night touches our hearts as we hear him saying, “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest”; “Him that cometh to me I will in no wise cast out”; “I go to prepare a place for you, that where I am there ye may be also.” That shows the spirit of the child that was born that night in Bethlehem, in a stable.

As to the keeper of the inn,— if there was one,— who did not make a place for Mary and Joseph, and the guests who did not give up their quarters, there is not so much to be said against them, after all. For, in the first place, they probably were not better nor worse than most people of that day. It was the fault of the times rather than of the men. The better usages of our day are due to the coming of Christ. Forgetting this, we are apt to judge the men of other times by the standard of our own. We must think how little light some people have. We do not ourselves see as well in the night as at noonday. We must remember that the principles taught by the Saviour have been working in the world now for more than eighteen centuries, and this makes a great difference between our day and the night when Christ was born.

In the Christian world today there is a humane spirit that was not known in the ancient world. New ties bind people together. There is a spirit of good will that not only goes down with sympathy and aid to the lowest, but goes out beyond the bounds of neighborhood and nation to the most remote. It is still too much and too often disregarded, but it is gaining strength, and is to rule the world. It is the spirit of the child that was born in Bethlehem. From that manger, on through ages that were dark, it has come down to us. Honor for women, care for children, regard for strangers, pity for the suffering, the generous feeling that seeks to lift burdens, to allay grief, good will to all, were set forth in the life of Christ as they never had been before. We must answer for the use we make of this light; but the people in that inn did not have it, and are not to be judged by it.

In the second place, the keeper of that inn in Bethlehem — if there was one — may have acted on the same principle with many now who keep a public house. It was a very busy time in Bethlehem. Natives of the place were crowding in from all the country round. Some of them may have had a wide reputation. But this couple, — no one knew who they were. If it had been a man like Annas, the high priest, or the rich Nicodemus, some way would have been found to keep him overnight; but a man of no reputation, coming along as Joseph did, with Mary, would stand a poor chance in the best hotels today. The looks of the couple and their baggage — if they had any — went against them. They did not drive up with a chariot and servants, as Naaman did to the door of the house of Elisha. That sort of arrival now makes the proprietor and the porter very attentive. But such a couple as Joseph and Mary, — to take them in might give offense to those already there. All that now hallows the name of that child and his mother was then unknown.

And what may have been still more against them was the fact that they were poor. Their outfit showed it, no doubt. They had no money, and were treated accordingly. The Savior may have been told of this afterwards by his mother. When he grew up he became the champion of the poor. One way to please him now is to befriend the friendless. He will keep it in mind and take it as done to himself, and at last from the throne of his glory will say, “I was a stranger, and ye took me in.”

To be a stranger, and poor at that, is a hard lot. In the Bible the one that stands for all those who are neglected is “he that hath no money.” And as yet we see only the dawn of a better day. For, “What is a man worth?” in our mother tongue still means, how much money has he? As much as to say, “If he has no money, he is worth nothing.”

Not so much a wonder then, after all that Joseph and Mary fared badly at the inn. If they had been rich, perhaps they might have had a place, but as they had no money there was no room for them; they might go to the stable.

Who can tell the straits people have been brought into for the want of money! Giving up the luxury they had been brought up in, putting the old homestead, where they were born, and where their fathers had lived, under the hammer of the auctioneer, dropping out of the social circle in which they had been delighted to move, pinching at every point where once they had been lavish of expense, seeing their loved ones suffer for lack of comforts which they can no longer afford to buy, tempted to dishonor, — all for the want of money; the averted look, the cold shoulder, perhaps the sneer, for no earthly reason but this, that they have lost their property.

Noble exceptions to this there are, increasing in numbers with each returning Christmas, of those who, undazzled by the glitter of wealth, undismayed by the signs of want, estimate a family by the worth of character that is in them rather than by the cost of the clothing that is on them or the size of the house in which they live. In this they are followers of him “who, though he was rich, for our sakes became poor,” who was born in a stable and cradled in a manger. True to that pre-existent love and lowly birth, he makes the richest offers of his grace to the poor, — not exclusively, but expressly. And when from all the world he would single out one who should represent the world, to whom he would make known his richest promise, the man to whom he looked was that same poor man, — “he that hath no money.”

And now on his throne in heaven he remembers his humble birth, and puts within the reach of the lowest the terms of heavenly life, sending forth this latest message, “Whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely!”

When is it that we learn best the mind that was in Christ? Is it not when we see him living with the poor, having compassion on them, teaching them and healing their sick? When we see him who was born in a stable, meeting, whichever way he turned, the dark frown, the malignant eye, the whispered sneer, the pitiless look, the insulting taunt, — yet giving out treasures of truth and love with unabated meekness, and answering blows with prayers for those who despitefully used him? In these things we come to know the mind of Christ.

If ever we are tempted to lament our lowly lot, we may compare it with that of the Savior, and take heart. He was born in a stable, he had not where to lay his head, — yet his position was high enough, his means were ample, for him to show his greatness. Let us, then, not keep thinking how much we would do if only we had the means, but think this, rather: How much are we doing with the means we have? The best that could be said of anyone with truth was said of one who was found fault with for doing what she did, “She hath done what she could.”

In the third place, it is not enough that we think how the Savior was treated that night in Bethlehem. It concerns us more to think how we are treating him ourselves.

“Oh,” you say, “we did not have a chance; we would not have treated him so.”

“But,” he says, “you do have a chance.”

You say again, “We had no place in that inn, and how could we keep him out?”

But you have a room in your own house; do you give him that? Many delightful visits you have enjoyed with your friends whom you had invited; did you ever have one with him? How long have you been keeping house? How is it at your office or school? Is there any room for him there? You have put up with great inconvenience for some friends; did you ever put yourself out any for him? How much room in our heart and life do we allow for him?

He does not now come in bodily form; but by his Spirit he comes to every heart, not by force that would destroy, but by love that would persuade. He respects our proprietorship, such as it is; at the most it is only stewardship. He asks our consent. He will not abide with us against our will. He is waiting now our answer: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If any man” — that is he knocking at the door of every heart — “if any man hear my voice and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.” So, then, he may be kept out from our hearts as truly as he was from the inn at Bethlehem. So present is he by his Spirit and his word, and we are keeping him out of our hearts so far as we fail to give him a welcome. Does he have the place he is seeking now in our thoughts? Or are we shutting him out? Does he have the best place in our love, or about the poorest? The largest place in our life, or none?

Is he waiting to be received by us, and is any one still putting him off, from the pressure of other things? If so, it is just what we disapprove in that innkeeper with the little light he had. He did not know who it was that he was turning away; he had no means of knowing. Perhaps if he had known, he would not have suffered the child to be born in a stable and laid in a manger.

But we do know him. To us the child is born. He comes to us who know the story of his birth and life, his grace and truth, his power and love, his lowliness and meekness and long-suffering. Since that night in Bethlehem we have seen him in Nazareth and Capernaum, in Jericho and Jerusalem, in Bethany and Gethsemane, on Calvary and Olivet. He has opened the eyes of the blind, stilled the raging of the sea, healed the sick, made the lepers clean, and called the dead to life. We have watched him in festive scenes and in seasons of grief. He has shed light on our path so that we need no longer to walk in darkness, but may have the light of life. He has spoken words of more power to guide, to comfort, to bless, than those of anyone else that ever was born. The brightest hope that is known in the world shines forth from his word. The noblest deeds that have been done in the world have been prompted by his Spirit. The purest lives that have been lived in the world have been formed after his example. By his Spirit he is doing more today than any one else that ever lived in the world to make the world better for the life that now is.

All this is no news to us. He comes to us today, bearing proofs infallible and uncounted of his truth and love. Is there one here, who, knowing all this, has no room for him?

Who are those whom you do receive instead of him? In our day, those who keep a hotel keep a record of all the guests, — when they came, where they came from, what their names are, and what rooms they have. We do not learn from Solomon how to keep a hotel, but it is written in the Proverbs, “Keep thy heart with all diligence.” There must be a register, if it is anything like a hotel,— that’s your memory; and a clerk,— that’s your conscience; so, if you want to find out how it is that there is no room in your heart for the Savior, all you have to do is to ask the clerk, or look at the book. Sometimes the best rooms are filled with desires for pleasures, or even the whole inn is taken up in that way, for there is a large party of them.

This does not mean that where the Savior is there is an end of pleasure; but where the whole heart is given up to pleasure-seeking, there is no room left for him; room enough for self-indulgence, but no room for self-denial; room enough for a dance, but not for a prayer meeting; room enough for outward adorning, — the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eye, and the pride of life, — but not for the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit; room enough to meet the demands of the table, of dress, of style, for books, pictures, study, travel, but for the living incarnation of the Son of God in the person of his poor, for the work of the church, for the conversion of the world, — no room! “Very sorry, but the house is full; no room left — but the stable! Might go there!”

Now there are pleasures — and pleasures. And those pleasures that cannot stay in the heart if Christ is received, it would be better to turn them out. There will be enough left. The house will not run down. He will bring enough others to make good their places. There are not any that would need to leave except those that are bad, — not one. All the others can stay with Christ, only some may need to take a smaller room; they are excessive. There is plenty of room for the children, with their sports, for all the wholesome pleasures of the table, for all the joys of domestic and social life. On these the Savior never frowned. Any guest but sin will find in him good company. There is room for amusement, but not the whole house, for that is not the end for which we were made.

But it may not be pleasure that leaves no room for the Savior; it may be business; everything is given up to that. It takes every room, — all the time and thought and strength. The reason some people cannot get out to a religious meeting, or take up Christian work, is business. No room for a family altar, — the house is full. Perhaps they work so hard all the week that they cannot get up in season Sunday morning to get to church; but that is business. Business claims so much that there is left no room for the Savior.

Now the proprietor of such a house, knowing who the Savior is, ought to say to those guests: “Whoever is to be turned away from my house, it must not be the Savior. There is room enough for him with all the business that I ought to do. Business that keeps him out is bad business, or too much business for me.”

Every day of our life the Savior has come to us, but Christmas especially reminds us of it. If you have given him no room as yet, will you not receive him today?

“As many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God.” Make room in your heart and life for him.

“Turn out his enemy and thine;

Turn out thy soul-enslaving sin,

And let the heavenly stranger in.”