Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Famous Frontiersmen and Heroes of the Border, by Charles H. L. Johnston (published 1913).

When Lewis and Clark were on their way to the Pacific coast they had with them two trappers, one of whom was to meet with extraordinary adventures. These were John Colter [1] and Lemuel Potts—both sturdy sons of the West—who obtained permission from the leaders of the expedition to remain near the headwaters of the Missouri River, in order to hunt and to trap. They intended to overtake the main body, after a short time, and hoped to obtain enough beaver skins to net them a good sum of money upon their return to civilization. You probably remember that Lewis had trouble with the Blackfeet, when near the Missouri, one of whom he had to kill because he began to run off the horses. For this reason these two trappers knew that they would have to use extreme caution or else they would fall into the clutches of some of these savages. The vengeance of an Indian is always swift and sure.

Knowing that the redskins were all about them, the trappers decided upon the following plan: they would lie hidden during the day, would set their traps late in the evening, and would visit them in order to remove the game in the gray of the early morning. Success met their efforts, and, before long, they had a goodly quantity of skins. No Indians were seen, although Indian sign was abundant, and they knew that there were plenty of Blackfeet in the vicinity.

One morning, while paddling up a winding stream where numerous traps were set, to their keen ears came the sound of heavy tramping.

“Those are redskins,” whispered Colter. “Let’s decamp at once, and get back to our starting-place.”

But Potts thought differently.

“Those are buffalo,” said he. “Wait until we round the corner and you will find out that I am right.”

Just then they swirled around the bend in the stream, and to their dismay, found both banks fairly swarming with Blackfeet. Escape was impossible, and, although cold shivers began to run up and down his spine, Colter ran the bow of the canoe towards the bank.

The red men began to whoop loudly, as they saw them approach, and called to them to come ashore. This they did, and, as they stepped upon the bank, a burly savage jumped forward and snatched the rifle which Potts carried, from his hand. Colter was a man of great physical strength and courage, who was not afraid of twenty savages. He wrested the weapon away from the redskin, handed it back to Potts, and confronted the startled braves with a face filled with determination and fire. Potts jumped into his canoe, pushed out into the stream, and started to paddle away, in spite of the commands of Colter, who cried to him to come back and take him with him.

Suddenly an arrow whizzed from the bank and Potts cried out, “I’m wounded, Colter. I cannot come to your assistance.”

In spite of this, he raised his rifle, fired, and killed the redskin who had shot him. A wild yelping now arose from the other savages, and, before five minutes had passed, the body of Potts fell into the water, riddled with hundreds of arrows.

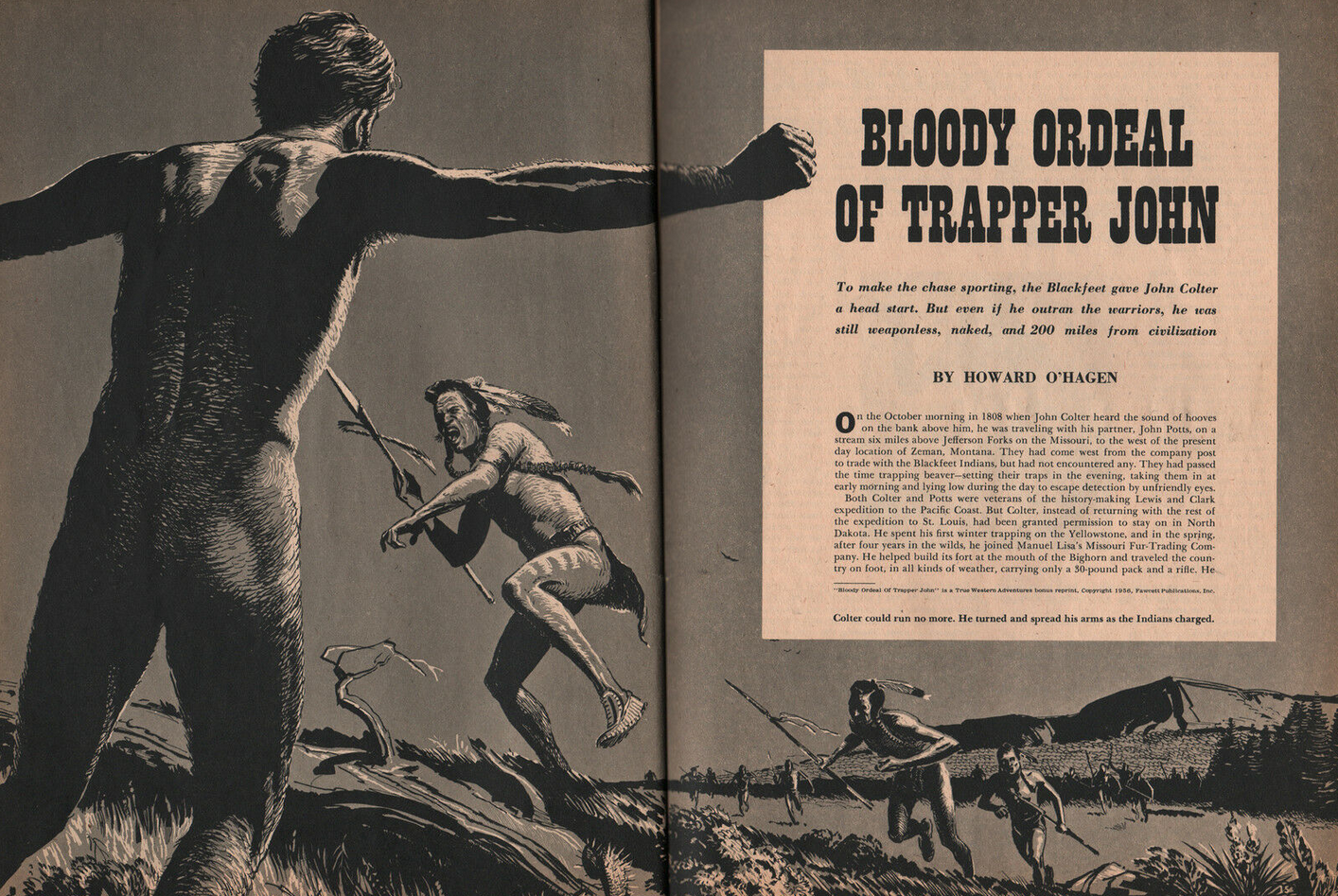

Colter stood upon the bank, unarmed and alone. The Blackfeet swarmed around him; stripped him of his clothes and then held a pow-wow, while they determined what they should do with him.

“Let’s skin him alive!” said one.

“No, whip him to death!” suggested another.

“Burn him at the stake!” shouted a great many.

The wrangling thus continued, until it was decided to let him run a race for his life. He was to get away if he could, but, if he could not, he was to be burned at the stake. All seemed to be much pleased at this decision.

A chief now approached the captive and said: “Paleface, you run fast, eh?”

“No, no, chief,” answered the trapper, “I am very poor runner, I slow as the tortoise.”

This was an untruth, for Colter was one of the swiftest foot racers upon the border, but his reply was hailed with loud shouts. Led upon a sandy plain by the chief, he was followed by six hundred armed red men, who gave him a start of three hundred yards, and then told him to go.

As Colter dashed away, a fierce whoop arose from all the red men and they started in pursuit with continued yelping. In a few moments they saw that it would take their swiftest runners to overhaul the white man, for he sped along like a greyhound. They had, however, a great advantage over him, for his feet were naked, and there were prickly plants, sand bars, and sharp stones upon the plain. Their feet, on the other hand, were protected by stout deer-skin moccasins.

On, on, sped the gallant scout, although his feet were cruelly lacerated by the stones and shrubs. On, on, he went, while the shouting of the red men died away, as they perceived that he was out-distancing them. None caught up to him, in fact, he drew rapidly away from the very swiftest of them all.

After a run of three miles Colter glanced back over his shoulder and saw that one of his pursuers was holding his own with him. He had headed towards the Jefferson Fork of the Missouri River, and knew that if he once reached the water he could doubtless hide himself. The pursuing red man had a spear in his hand, and, so fleet was he, that he was soon within a hundred yards of the trapper.

“If I do not stop this Indian,” said Colter to himself, “it is all over with me.”

Straining every muscle in order to get away, Colter suddenly felt the blood gushing from his nose, and knew that a slight hemorrhage had been occasioned by his efforts. He was but a mile from the river, and, again looking back, saw the Indian within twenty yards of him. Escape was now impossible. Turning swiftly around,—he stood absolutely still and opened his arms.

The red man was astounded at this unexpected action, and, in endeavoring to check his headway, fell to the ground. The lance, meanwhile, flew from his hand and stuck into the earth a considerable distance from him, where it broke off. Luck was with the half-winded man of the plains, who now turned about, seized the broken spear-head, and darted swiftly to the side of the prostrate red man.

The trapper aimed the sharp lance at the Indian, and drove it into him with such force that he was pinned to the earth. A deep groan came from the helpless brave, as the backwoodsman again turned to run towards the river, although he was now exhausted by loss of blood and by the terrible race for life. His pursuers were still far behind, and he reached Jefferson’s Fork so far ahead of them that they could not see him. One spring—he had leaped into the water—and was swimming towards a little island about a hundred yards from the bank.

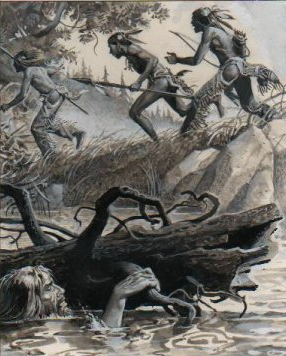

Upon the edge of this had lodged a clump of sticks and floating brush. Colter made for it and dove beneath the tangled mass; emerging somewhere in its centre, with his head between two giant logs. Breathing with great difficulty, and faint from his exhausting run, he waited with throbbing heart for the red men to arrive. This they did very shortly.

They had stopped beside the body of their comrade and found that he was in his death-agony. Infuriated by this, and with terrific yells, they again set out in pursuit of Colter, who heard their vindictive screeching as they reached the bank. Some of them swam out to the island and punched about in the drift with their spears. As they did so, the trapper drew down in the water so that only his nose was exposed. He remained thus for about half an hour, when the redskins gave up their search and returned to the body of the fallen chieftain. Colter feared that they might set fire to the drift, but this idea did not seem to have entered the minds of the Blackfeet, who began a hideous wailing as they gathered around their leader. Carrying him upon their shoulders, they started back to their camp, and gradually their wild lamentations died away in the shadows of the forest.

The trapper was in a desperate predicament, for he was without either clothes or rifle. His feet had been lacerated by the stones and plants so that he could walk only with difficulty, and his body was chilled by his long immersion in the cold waters of the river. Certainly there was no brilliant prospect before him, for he was miles from any settlement. Would you not think that he would have become absolutely disheartened and would have given up in despair?

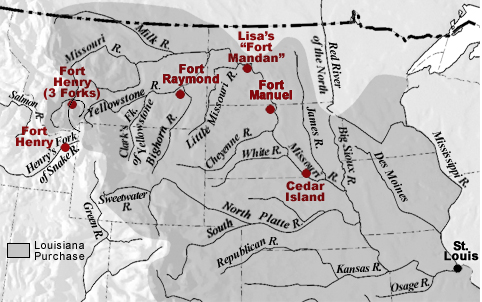

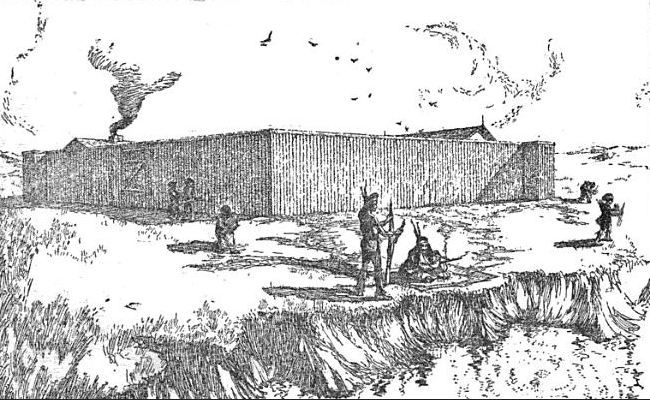

Not so with this bold follower of Lewis and Clark. After a day’s rest and a meal of berries, grass and stalks from a shrub known as the sheep sorrel, he started for Lisa’s Fort on the Yellowstone, a distance of a week’s hard journey. Fortune favored this man of iron. Toads, frogs, and insects became his food, and with clothing of bark and reeds he finally reached the hospitable shelter of Manuel Lisa’s trading station. He was scarcely recognizable.

Colter had suffered untold agony from thirst, from hunger and from cold. The evenings are chilly in this country—even in summer—and, although he made a fire by rubbing two dry sticks together, he shivered all through the night. The wild sheep sorrel had given him most needed nourishment, while the body of a dead rabbit, which he fortunately stumbled upon, had brought sufficient strength to carry him to the Fort. No wonder that the trappers there gave three rousing cheers for this frontier hero.

In ten days after his arrival at the group of log huts, John Colter was again fit for service, but Lewis and Clark were already far away upon their transcontinental journey. He remained at the Fort, had several brushes with the Blackfeet, and eventually found his way back to the settlements, where he was much admired for his nerve and courage in eluding the wild denizens of the plains near the headwaters of the Missouri. Certainly he had good reason to be proud of his escape from the bloodthirsty hands of the Blackfoot warriors. Three cheers for brave John Colter! He well deserves to be remembered as a Marathon runner who ran a more thrilling race than the tame affairs of the present day, where no band of savages, who are thirsting for one’s gore, pursue the struggling athletes.

________________________

[1] In the original text, the author mistakenly uses the name Samuel Colter. This has been corrected to John Colter throughout.

Entertaining yarn, but seems to have a bit more…editorializing…than your typical offerings Mr. Mantel. Good find nonetheless, and an enjoyable read.

I first read about Colter’s run in 4th grade. Harrowing stuff.