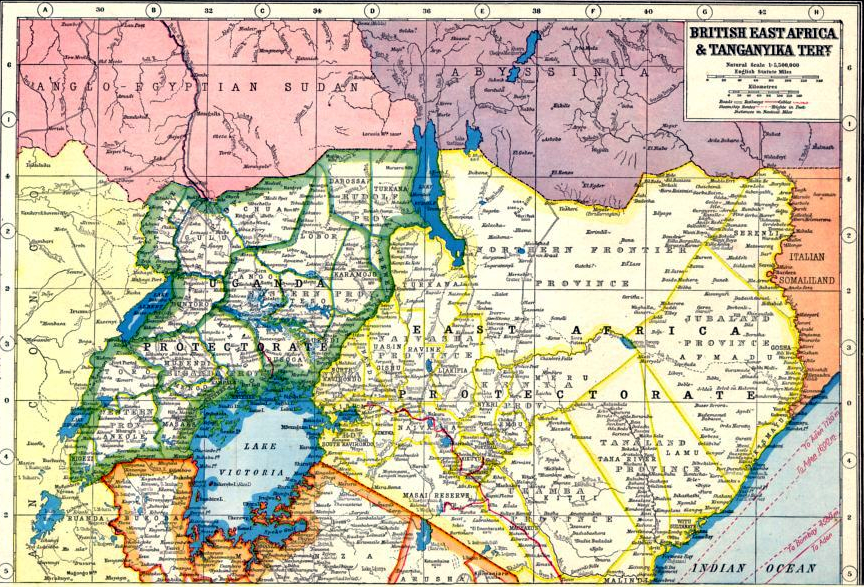

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from My African Journey, by Winston Spencer Churchill (published 1909). All spelling in the original.

It took no little time to stow all our baggage, food and tents upon the launch and its steel boats, and though our camp was astir at half-past three, the dawn was just breaking when we were able to embark. And then the James Martin wedged herself upon a rock a few yards from the shore of the sheltering inlet, and seemed to have got herself hard and fast; for pull as we might with all the force of the launch at full steam, and the added weight of the current to help us, not an inch would she budge. Everything had, therefore, to be unloaded again from the straggler, and when she had thus been lightened and her freight transferred to the attendant canoes, James Kago ordered his tribesmen to leap into the water, which was not more than five feet deep, and push and lift the little vessel whilst the steamer tugged. But this task the natives were most reluctant to perform out of fear of the crocodiles, who might at any moment make a pounce, notwithstanding all the noise and clatter. Thereupon the energetic chief seized hold of them one after another round the waist, and threw them full-splash into the stream, till at least twenty were accumulated round the boat, and then, what with their impatience to finish their uncomfortable job and our straining tow rope, the James Martin floated free, was reloaded, and we were off.

As we drifted out into mid-stream the most beautiful view of the falls broke upon us. It was already almost daylight, but the sun had not yet actually topped the great escarpment over which the Nile descends. The banks on both sides of the river, clad with dense and lofty forest and rising about twice as high as Cliveden Woods from the water’s edge, were dark in shadow. The river was a broad sheet of steel grey veined with paler streaks of foam. The rock portals of the falls were jetty black, and between them, illumined by a single shaft of sunlight, gleamed the tremendous cataract—a thing of wonder and glory, well worth travelling all the way to see.

We were soon among the hippopotami. Every two or three hundred yards, and at every bend of the river, we came upon a herd of from five to twenty. To us in a steam launch they threatened no resistance or danger. But their inveterate hostility to canoes leads to repeated loss of life among the native fishermen, whose frail craft are crumpled like eggshells in the snap of enormous jaws. Indeed, all the way from here to Nimule they are declared to be the scourge and terror of the Nile. Fancy mistaking a hippopotamus—almost the largest surviving mammal in the world—for a water lily. Yet nothing is more easy. The whole river is dotted with floating lilies detached from any root and drifting along contentedly with the current. It is the habit of the hippo to loll in the water showing only his eyes and the tips of his ears, and perhaps now and again a glimpse of his nose, and thus concealed his silhouette is, at three hundred yards, almost indistinguishable from the floating vegetation. I thought they also looked like giant cats peeping. So soon, however, as they saw us coming round a corner and heard the throbbing of the propeller, they would raise their whole heads out of the water to have a look, and then immediately dive to the bottom in disgust. Our practice was then to shut off steam and drift silently down upon them. In this way one arrives in the middle of the herd, and when curiosity or want of air compels them to come up again there is a chance of a shot. One great fellow came up to breathe within five yards of the boat, and the look of astonishment, of alarm, of indignation, in his large, expressive eyes—as with one vast snort he plunged below—was comical to see. These creatures are not easy to kill. They bob up in the most unexpected quarters, and are down again in a second. One does not like to run the risk of merely wounding them, and the target presented is small and vanishing. I shot one who sunk with a harsh sort of scream and thud of striking bullet. We waited about a long time for him to float up to the surface, but in vain, for he must have been carried into or under a bed of reeds and could not be retrieved.

The Murchison, or Karuma, Falls, as the natives call them, are about thirty miles distance from the Albert Lake, and as with the current we made six or seven miles an hour, this part of our journey was short. Here the Nile offers a splendid waterway. The main channel is at least ten feet deep, and navigation, in spite of shifting sandbanks, islands, and entanglements of reeds and other vegetation, is not difficult. The river itself is of delicious, sweet water, and flows along in many places half-a-mile broad. Its banks for the first twenty miles were shaded by beautiful trees, and here and there contained by bold headlands, deeply scarped by the current. The serrated outline of the high mountains on the far side of the Albert Nyanza could soon be seen painted in shadow on the western sky. As the lake is approached the riparian scenery degenerates; the sandbanks became more intricate; the banks are low and flat, and huge marshes encroach upon the river on either hand. Yet even here the traveller moves through an imposing world.

At length, after five or six hours’ steaming, we cleared the mouth of the Victoria Nile and swam out on to the broad expanses of the lake. Happily on this occasion it was quite calm. How I wished then that I had not allowed myself to be deterred by time and croakers from a longer voyage, and that we could have turned to the south and, circumnavigating the Albert, ascended the Semliki river with all its mysterious attractions, have visited the forests on the south-western shores, and caught, perhaps, a gleam of the snows of Ruenzori! But we were in the fell grip of carefully-considered arrangements, and, like children in a Christmas toy shop always looking back, were always hurried on.

Yet progress offered its prizes as well as delay. Some of my party had won the confidence of the engineer of the launch, who had revealed to them a valuable secret. It appeared that “somewhere between Lake Albert and Nimule”—not to be too precise—there was a place known only to the elect, and not to more than one or two of them, where elephants abounded and rhinoceros swarmed. And these rhinoceros, be it observed, were none of your common black variety with two stumpy horns almost equal in size, and a prehensile tip to their noses. Not at all; they were what are called “white” rhino—Burchell’s white rhinoceros, that is their full style—with one long, thin, enormous horn, perhaps a yard long—on their noses, and with broad, square upper lips. Naturally we were all very much excited, and in order to gain a day on our itinerary to study these very rare and remarkable animals more closely, we decided not to land and pitch a camp, but to steam on all through the night. Meanwhile our friend the engineer undertook to accomplish the difficult feat of finding the channel, with all its windings, in the dark.

The scene as we left the Albert Lake and entered the White Nile was of surpassing beauty. The sun was just setting behind the high, jagged peaks of the Congo Mountains to the westward. One after another, and range behind range, these magnificent heights—rising perhaps to eight or nine thousand feet—unfolded themselves in waves of dark plum-coloured rock, crested with golden fire. The lake stretched away apparently without limit like the sea, towards the southward in an ever-broadening swell of waters—flushed outside the shadow of the mountains into a delicious pink. Across its surface our tiny flotilla—four on a string—paddled its way towards the narrowing northern shores and the channel of the Nile.

The White Nile leaves the Albert Lake in majesty. All the way to Nimule it is often more like a lake than a river. For the first twenty miles of its course it seemed to me to be at least two miles across. The current is gentle, and sometimes in the broad lagoons and bays into which the placid waters spread themselves it is scarcely perceptible. I slept under an awning in the Kisingiri, the last and smallest boat of the string, and, except for the native steersman and piles of baggage, had it all to myself. It was, indeed, delightful to lie fanned by cool breezes and lulled by the soothing lappings of the ripples, and to watch, as it were, from dreamland the dark outlines of the banks gliding swiftly past and the long moonlit levels of the water.

At daybreak we were at Wadelai. In twenty-four hours from leaving Fajao we had made nearly a hundred miles of our voyage. Without the sigh of a single porter these small boats and launch had transported the whole of our “safari” over a distance which would on land have required the labours and sufferings of three hundred men during at least a week of unbroken effort. Such are the contrasts which impress upon one the importance of utilising the water-ways of Central Africa, of establishing a complete circulation along them, and of using railways in the first instance merely to link them together.

Wadelai was deserted. Upon a high bank of the river stood a long row of tall, peaked, thatched houses, the walls of a fort, and buildings of European construction. All was newly abandoned to ruin. The Belgians are evacuating all their posts in the Lado enclave except Lado itself, and these stations, so laboriously constructed, so long maintained, will soon be swallowed by the jungle. The Uganda Government also is reducing its garrisons and administration in the Nile province, and the traveller sees, not without melancholy, the spectacle of civilization definitely in retreat after more than half a century of effort and experiment.

We disembarked and climbed the slopes through high rank grass and scattered boulders till we stood amidst the rotting bungalows and shanties of what had been a bold bid for the existence of a town. Wadelai had been occupied by white men perhaps for fifty years. For half a century that feeble rush-light of modernity, of cigarettes, of newspapers, of whisky and pickles, had burned on the lonely banks of the White Nile to encourage and beckon the pioneer and settler. None had followed. Now it was extinguished; and yet when I surveyed the spacious landscape with its green expanses, its lofty peaks, its trees, its verdure, rising from the brink of the mighty and majestic river, I could not bring myself for a moment to believe that civilization has done with the Nile Province or the Lado Enclave, or that there is no future for regions which promise so much.

All through the day we paddled prosperously with the stream. At times the Nile lost itself in labyrinths of papyrus, which reproduced the approaches to Lake Chioga, and through which we threaded a tortuous course, with many bumps and brushings at the bends. But more often the banks were good, firm earth, with here and there beautiful cliffs of red sandstone, hollowed by the water, and rising abruptly from its brim, crowned with luxuriant foliage. In places these cliffs were pierced by narrow roadways, almost tunnels, winding up to the high ground, and perfectly smooth and regular in their construction. They looked as if they were made on purpose to give access to and from the river; and so they had been—by the elephants. Legions of water-fowl inhabited the reeds, and troops of cranes rose at the approach of the flotilla. Sometimes we saw great, big pelican kind of birds, almost as big as a man, standing contemplative on a single leg, and often on the tree-tops a fish-eagle, glorious in bronze and cream, sat sunning himself and watching for a prey.

I stopped once in the hope of catching butterflies, but found none of distinction—only a profuse variety of common types, a high level of mediocrity without beauties or commanders, and swarms of ferocious mosquitoes prepared to dispute the ground against all comers; and it was nearly four in the afternoon when the launch suddenly jinked to the left out of the main stream into a small semi-circular bay, five hundred yards across, and we came to land at “Hippo Camp.”

We thought it was much too late to attempt any serious shooting that day. There were scarcely three and a half hours of daylight. But after thirty-six hours cramped on these little boats a walk through jungle was very attractive; and, accordingly, dividing ourselves into three parties, we started in three different directions—like the spokes of a wheel. Captain Dickinson, who commanded the escort, went to the right with the doctor; Colonel Wilson and another officer set out at right angles to the river bank; and I went to the left under the guidance of our friend the engineer. I shall relate very briefly what happened to each of us. The right-hand party got, after an hour’s walking, into a great herd of elephants, which they numbered at over sixty. They saw no very fine bulls; they found themselves surrounded on every side by these formidable animals; and, the wind being shifty, the hour late, and the morrow free, they judged it wise to return to camp without shooting. The centre party, consisting of Colonel Wilson and his companion, came suddenly, after about a mile and a half’s walk, upon a fine solitary bull elephant. They stalked him for some time, but he moved off, and, on perceiving himself followed, suddenly, without the slightest warning on his part and no great provocation on theirs, he threw up his trunk, trumpeted, and charged furiously down upon them; whereupon they just had time to fire their rifles in his face and spring out of his path. This elephant was followed for some miles, but it was not for three months afterwards that we learned that he had died of his wounds and that the natives had recovered his tusks.

So much for my friends. Our third left party prowled off, slanting gradually away inland from the river’s bank. It was a regular wild scrub country, with high grass and boulders and many moderate-sized trees and bushes, interspersed every hundred yards or so by much bigger ones. Near the Nile extensive swamps, with reeds fifteen feet high, ran inland in long bays and fingers, and these, we were told, were the haunts of white rhino. We must have walked along warily and laboriously for nearly three-quarters of an hour, when I saw through a glade at about two hundred yards distance a great dark animal. Judging from what I had seen in East Africa, I was quite sure it was a rhinoceros. We paused, and were examining it carefully with our glasses, when all of a sudden it seemed to treble in size, and the spreading of two gigantic ears—as big, they seemed, as the flaps of French windows—proclaimed the presence of the African elephant. The next moment another and another and another came into view, swinging leisurely along straight towards us—and the wind was almost dead wrong.

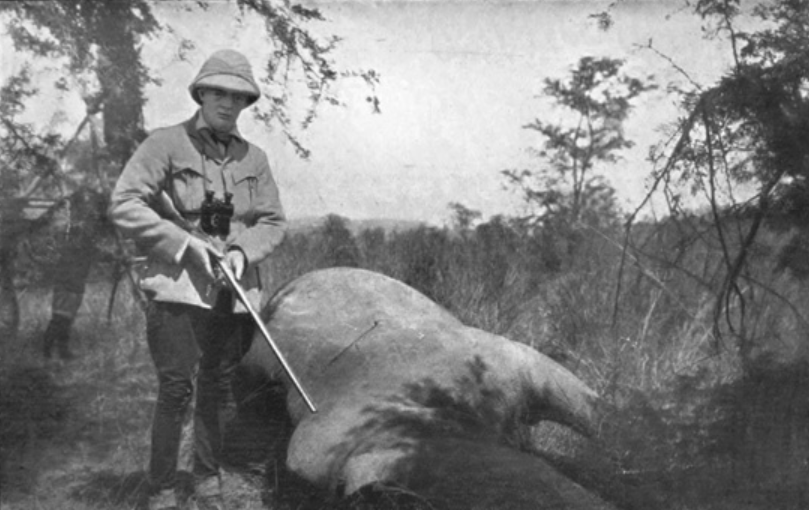

We changed our position by a flank march of admirable celerity, and from the top of a neighbouring ant-bear hill watched, at the distance of about one hundred and fifty yards, the stately and awe-inspiring procession of eleven elephants. On they came, loafing along from foot to foot—two or three tuskers of no great merit, several large tuskless females, and two or three calves. On the back of every elephant sat at least one beautiful white egret, and sometimes three or four, about two feet high, who pecked at the tough hide—I presume for very small game—or surveyed the scene with the consciousness of pomp. These sights are not unusual to the African hunter. Those who dwell in the wilderness are the heirs of its wonders. But to me I confess it seemed a truly marvellous and thrilling experience to wander through a forest peopled by these noble Titans, to watch their mysterious, almost ghostly, march, to see around on every side, in large trees snapped off a few feet from the ground, in enormous branches torn down for sport, the evidences of their giant strength. And then, while we watched them roam down towards the water, I heard a soft swishing sound immediately behind us, and turning saw, not forty yards away, a splendid full-grown rhinoceros, with the long, thin horn of his rare tribe upon him—the famous white rhinoceros—Burchell himself—strolling placidly home after his evening drink and utterly unconscious of the presence of stranger or foe!

We had very carefully judged our wind in relation to the elephants. It was in consequence absolutely wrong in relation to the rhinoceros. I saw that in another fifty yards he would walk right across it. For my own part, perched upon the apex of a ten-foot ant-bear cone, I need have no misgivings. I was perfectly safe. But my companions, and the native orderlies and sailors who were with us, enjoyed no such security. The consequences of not killing the brute at that range and with that wind would have been a mad charge directly through our party. A sense of responsibility no doubt restrained me; but I must also confess to the most complete astonishment at the unexpected apparition. While I was trying to hustle the others by signals and whispers into safer places; the rhino moved steadily, crossed the line of wind, stopped behind a little bush for a moment, and then, warned of his danger, rushed off into the deepest recesses of the jungle. I had thrown away the easiest shot I ever had in Africa. Meanwhile the elephants had disappeared.

We returned with empty hands and beating hearts to camp, not without chagrin at the opportunity which had vanished, but with the keenest appetite and the highest hopes for the morrow. Thus in three hours and within four miles of our landing-place our three separate parties had seen as many of the greatest wild animals as would reward the whole exertion of an ordinary big-game hunt. As I dropped off to sleep that night in the little Kisingiri, moored in the bay, and heard the grunting barks of the hippo floating and playing all around, mingling with the cries of the birds and the soft sounds of wind and water, the African forest for the first time made an appeal to my heart, enthralling, irresistible, never to be forgotten.

At the earliest break of day we all started in the same order, and with the sternest resolves. During the night the sailors had constructed out of long bamboo poles a sort of light tripod, which, serving as a tower of observation, enabled us to see over the top of the high grass and reeds, and this proved of the greatest convenience and advantage, troublesome though it was to drag along. We spent the whole morning prowling about, but the jungle, which twelve hours before had seemed so crowded with game of all kinds, seemed now utterly denuded. At last, through a telescope from a tree-top, we saw, or thought we saw, four or five elephants, or big animals of some kind, grazing about two miles away. They were the other side of an enormous swamp, and to approach them required not only traversing this, but circling through it for the sake of the wind.

We plunged accordingly into this vast maze of reeds, following the twisting paths made through them by the game, and not knowing what we might come upon at every step. The ground under foot was quite firm between the channels and pools of mud and water. The air was stifling. The tall reeds and grasses seemed to smother one; and above, through their interlacement, shone the full blaze of the noonday sun. To wade and waddle through such country carrying a double-barrelled ·450 rifle, not on your shoulder, but in your hands for instant service, peering round every corner, suspecting every thorn-bush, for at least two hours, is not so pleasant as it sounds. We emerged at last on the farther side under a glorious tree, whose height had made it our beacon in the depths of the swamp, and whose far-spreading branches offered a delicious shade.

It was three o’clock. We had been toiling for nine hours and had seen nothing—literally nothing. But from this moment our luck was brilliant. First we watched two wild boars playing at fighting in a little glade—a most delightful spectacle, which I enjoyed for two or three minutes before they discovered us and fled. Next a dozen splendid water-buck were seen browsing on the crest of a little ridge within easy shot, and would have formed the quarry of any day but this; but our ambition soared above them, and we would not risk disturbing the jungle for all their beautiful horns. Then, thirdly, we came slap up against the rhinoceros. How many I am not certain—four, at least. We had actually walked past them as they stood sheltering under the trees. Now, here they were, sixty yards away to the left rear—dark, dim, sinister bodies, just visible through the waving grass.

When you fire a heavy rifle in cold blood it makes your teeth clatter and your head ache. At such a moment as this one is almost unconscious alike of report and recoil. It might be a shot-gun. The nearest rhino was broadside on. I hit him hard with both barrels, and down he went, to rise again in hideous struggles—head, ears, horn flourished agonizingly above the grass, as if he strove to advance, while I loaded and fired twice more. That was all I saw myself. Two other rhinos escaped over the hill, and a fourth, running the other way, charged the native sailors carrying our observation tower, who were very glad to drop it and scatter in all directions.

To shoot a good specimen of the white rhinoceros is an event sufficiently important in the life of a sportsman to make the day on which it happens bright and memorable in his calendar. But more excitement was in store for us before the night. About a mile from the spot where our victim lay we stopped to rest and rejoice, and, not least, refresh. The tower of observation—which had been dragged so painfully along all day—was set up, and, climbing it, I saw at once on the edge of the swamp no fewer than four more full-grown rhinoceros, scarcely four hundred yards away. A tall ant-hill, within easy range, gave us cover to stalk them, and the wind was exactly right. But the reader has dallied long enough in this hunter’s paradise. It is enough to say that we killed two more of these monsters, while one escaped into the swamp, and the fourth charged wildly down upon us and galloped through our party without apparently being touched himself or injuring any one. Then, marking the places where the carcasses lay, we returned homeward through the swamp, too triumphant and too tired to worry about the enraged fugitives who lurked in its recesses. It was very late when we reached home, and our friends had already hewn the tusks out of a good elephant which Colonel Wilson had shot, and were roasting a buck which had conveniently replenished our larder.

Such was our day at Hippo Camp, to which the ardent sportsman is recommended to repair, when he can get some one to show him the way.

Nice!