Yesterday, I met Royal Marine Commando George Edwin Pointer.

He is 93 and will be 94 later this year. Tomorrow he will be at the palace and meet Harry. He has been a few times and has met the queen.

He confirmed from memory all the things I had read in various books about the Royal Marine Commandos. The special training he received, his volunteering, and how he was first shipped out to Egypt and later took part in D-Day and subsequent battles to capture bridges to help the many soldiers of the Allied forces proceed through Germany as quickly as possible.

He confirmed from memory all the things I had read in various books about the Royal Marine Commandos. The special training he received, his volunteering, and how he was first shipped out to Egypt and later took part in D-Day and subsequent battles to capture bridges to help the many soldiers of the Allied forces proceed through Germany as quickly as possible.

He has a very sharp wit, making fun of his daughters, even as they interrupted his conversation with me from time to time, with this or that mundane comment.

He shared how he has the beginnings of Alzheimer’s and I, being somewhat familiar with men who have lived through much, directly told him he seemed very lucid to me, particularly on account of the fact that it was self-evident he was making fun of how he was being treated and how he used it to amuse himself. He chuckled and said, “Oh yes, I am sharp enough, but sometimes I forget names, like, you know.”

It took him a minute or two to recall the name of the general who had given them a few pep talks and whom he recalled at the very near end of the war. Then it came to him with a few gentle reminders. Monty. Montgomery.

He was shot a week or two before the end of the war in the thigh and shipped back home, where he spent a couple of years in hospitals around the country. His leg had developed gangrene and had to be amputated. He showed me the false leg matter of factly, when he described humbly how sometimes, living alone, he can fall over if he doesn’t mind his footing.

He had a cut on his arm from one such fall, which was almost healed. At his age, of course, it takes much longer for a simple injury to heal.

He described everything matter of factly and directly, without any embellishment and indeed only some of that self-effacing English understatement that I have seen only in Englishmen of his generation who had done things that, like his own actions, are written of in history books; he spoke with self-effacing humour of uncommon wit.

He was twenty-one when he lost his leg. He told me he’d met his wife as a result of “going over the wall, like” during his hospital stay to go out drinking with a few friends at the nearby pubs.

His wife passed away a few years ago, and in our conversation, he told me with the same direct way he had told me about losing his leg that when she died, his life ended really. He said they had been like twins, meaning Siamese twins I assumed, doing everything together all the time. He clearly had no fear of death and when his daughter asked him if he wanted a beer, he refused because he only liked a particular brand. His daughter reminded him she had brought that very beer along. He had a half pint and offered me the rest of his bottle. I politely declined. I was not going to drink half of the only two tins or so of the beer he liked. I had tea and listened to him and asked questions.

His wife passed away a few years ago, and in our conversation, he told me with the same direct way he had told me about losing his leg that when she died, his life ended really. He said they had been like twins, meaning Siamese twins I assumed, doing everything together all the time. He clearly had no fear of death and when his daughter asked him if he wanted a beer, he refused because he only liked a particular brand. His daughter reminded him she had brought that very beer along. He had a half pint and offered me the rest of his bottle. I politely declined. I was not going to drink half of the only two tins or so of the beer he liked. I had tea and listened to him and asked questions.

When I asked him about the training he received and weapons he was issued, he stated he’d mostly only had a rifle, though he did add, “you know, depending on what we had to do” in any particular action.

He did like grenades, though. His face lit up remembering them. “Oh yes, grenades are better than weapons… a lot of men were killed by those. They’re like small hand bombs, you know…” This obvious-sounding statement was probably lost on most people in the room, but I knew what he meant. This man had seen bombs. Real ones. That drop from planes, and the devastation they caused. That’s what he meant about grenades.

I asked him about the training in hand to hand combat because on my various researches into it, I had come to conclude that the training received in this was a mixture of mildly useful to farcical. He pretty much confirmed my view when he told me that they basically told you to just box with another lad. He is a tall man and must have been imposing in his youth. He said he couldn’t hit the other lad hard or he’d really hurt him and the other boy was scared of hitting him too, so they just tapped each other a bit and then shook hands and their drill instructor said, “All right, lads, enough of that.”

When I asked him about the training received by the Commandos, which I know was the precursor to SOE and eventually the SAS, he simply said: “Oh yes, I did all that business.”

Glossing over it, I expect, partly because it was a bit boring, as such training invariably is, and partly from a habit of not discussing such details.

It was somewhat surreal to realize I was sitting there, talking to a man who had not only lived through historical events, my own grandparents had done so too after all, and my great-grandfather had been a general and is mentioned in some history books. But this man was alive, in front of me, describing events that I only imagined from historical books I read or documentaries or films I watched, and is really the very embodiment of that type of English reserve and self-effacing dignity you mostly only read about in books today.

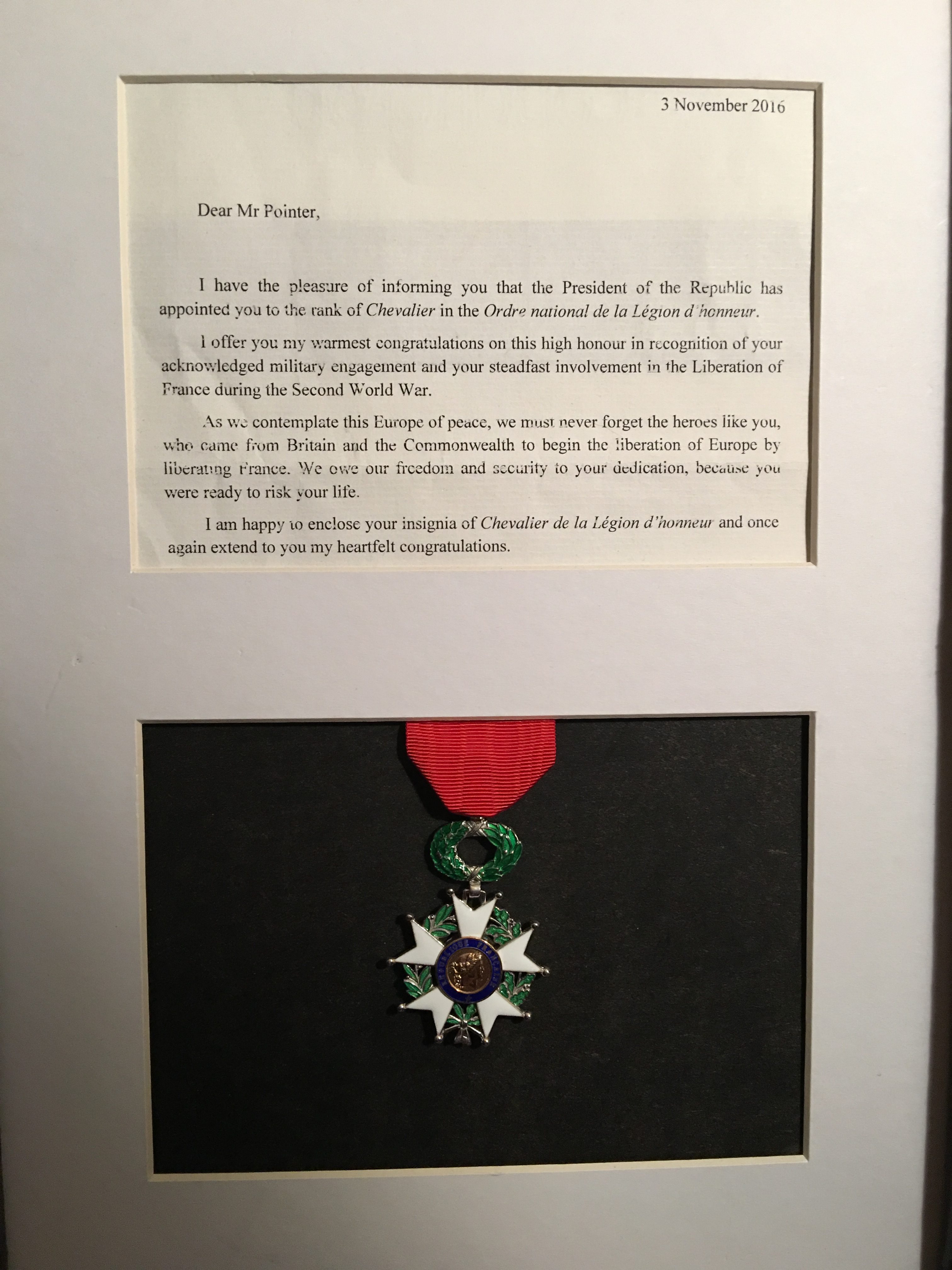

I asked him if it would be all right to take a few pictures of his medals and of him with his granddaughter. He graciously said it was fine.

Men like George Edwin Pointer quite literally saved Europe from a nightmare of death that only socialism and communism have ever achieved on the habitual and horrific industrial scales they invariably do. In all of human history, never have such levels of murderous evil taken place as the regimes created by socialists and communists with their anti-reality, inhuman demands of totalitarian submission to the party line and groupthink.

Men like George Edwin Pointer stopped them.

He lost friends doing so. He lost a leg doing so. And God only knows what else he suffered through his life in the quiet dignity he still conserves.

Tomorrow at the palace, the Queen’s grandson will once more recognize him for his sacrifices.

So should all of us.

And may his example remind men of my generation and after that at times, fighting evil means killing people. A lot. And sacrificing your health. And your future. And sometimes your life.

Thank you Mr. Pointer.

4.5

So, Kurgan, you were a godless heathen? How does that work then, seeing as Heathens did/do belong to a belief system that has gods/goddesses. Whether you believe in them or not is not the point. The point is that heathenism is not godless – they’re just not of the Jew-on-stick variety.

You realize that “godless heathen” is a normal phrase, right? Don’t get bogged down in semantics. His point was that he was not a Christian.

Autistic screeching noted.

5