Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Leading Figures in European History, by R. P. Dunn-Pattison (published 1912).

Go where you will over the Lowlands of Scotland or England, or in western Europe over the countries south of the Danube, you will seldom find a district that cannot boast of Roman remains. Here is a magnificent aqueduct; there a vast amphitheatre; at one place are sumptuous baths, with plumbing work that is still a pattern in these modern days; at another the ruins of some huge villa, its tessellated pavements and artistic remains the delight of all connoisseurs. All along the boundaries of this area you see mighty fortifications and the remains of fortresses, and inside a network of cleverly designed strategic roads. A glance at an ancient atlas will show you that the Roman Empire stretched from the Atlantic to the Rhine, from the Danube to the Sahara, from the Black Sea to the Desert of Arabia. Historians will tell you that by the third century, within these limits there was but one code of law, that all free inhabitants—after the Edict of Caracalla—had equal rights before the law; all were in the fullest sense Roman citizens; that, in a word, within the civilised world there was, for all intents and purposes, one state and one people.

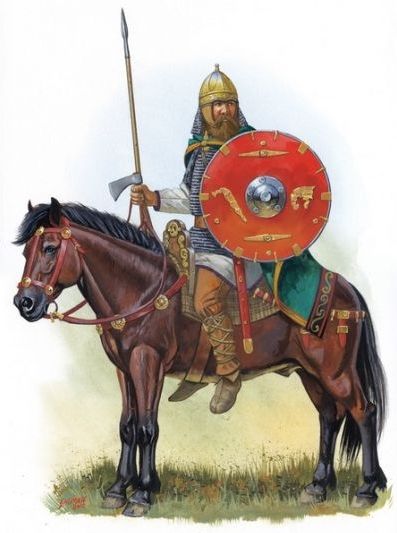

When you remember all this you will find it difficult to realise how such a vast and magnificently organised state fell before the incursion of the hordes of barbarians, whose civilisation was as much below that of Rome as is the Afghan below that of England in the present day. The reasons, however, are not far to seek. The mighty Roman Empire had lived upon itself; emperor had opposed emperor; civil war had eaten out the heart of the empire. Heavy taxation had brought about small families, and this race-suicide had been hastened by the devastation of great plagues. Meanwhile luxury had sapped energy: the practice of arms was no longer a national duty. The legions were full of barbarians, mere mercenaries, who often drifted home to show their fellow tribes the weakness of the Roman power. The frontiers were defended by an arrangement whereby the barbarians of Africa were sent to serve on the Danube or in Britain, while Britons and Teutons were sent to Africa and Spain. But there was no real national army to reinforce these frontier guards. The only troops retained at the seat of empire were the Jovians and Herculians, forming the emperor’s bodyguard. As the emperor’s power became more despotic the upper classes—as in France in the eighteenth century—were deprived to a great extent of political work: removed thus from the sphere of local and imperial politics, they became mere flunkeys at the emperor’s court, while the machinery of government was worked by a close bureaucracy. Thus it was that, when the swarm of barbarians swept away the few highly trained legionaries, there was no one to organise local defence, and the mass of the population, enervated by years of bad government, fell a spiritless and docile prey to their new masters.

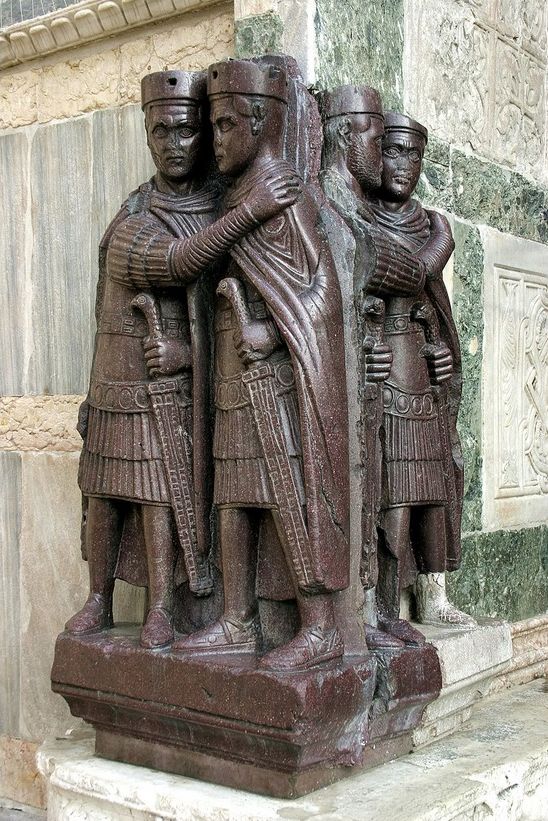

The more far-seeing emperors had recognised that the burden of empire was too heavy for one man, but they were powerless to introduce a new régime without demolishing their own power. Diocletian, indeed, in 303, had attempted to lighten the task of the emperor by associating three colleagues with himself. It was his intention that each of the two seniors should have the title of Augustus, and the two juniors should bear that of Caesar; when a vacancy occurred among the Augusti the senior Caesar would be promoted. Thus he hoped to secure a succession of trained emperors. One Augustus was appointed to Italy and one to the East, while one Caesar took the Danube, and the other the Rhine. Such a system, unfortunately, except in the case of very exceptional men, was bound to lead to a break up of the empire or to civil war. In 330 the Emperor Constantine, finding Italy too much exposed to barbarian inroads, moved the seat of empire from Rome to his newly chosen site on the Bosphorus, where stood the old Greek city of Byzantium. This strategic post on the lines of communication between Europe and the rich lands of Asia, was out of the track of the barbarian invaders from the North. Moreover, it brought the emperor into close communication with the sturdy peasantry of the uplands of Asia Minor, who produced the most famous soldiers within the eastern limits of the empire. It was to bind these soldiers to his cause that Constantine adopted Christianity as the state religion.

For the next one hundred and thirty years there were usually two emperors, one at Constantinople, the other in Italy; though, latterly, the Emperor of the West was merely the coadjutor of the Emperor of the East. Meanwhile, stream after stream of barbarians, Goths, Vandals, Huns and Burgundians, swept over the West. Save for the Huns all these tribes came rather to possess than to destroy. The Vandals occupied north-west Africa, the Visigoths Spain, the Ostrogoths Italy, and the Burgundians central France; gradually they formed for themselves new states. The contact with the empire affected them in three distinct ways. First, they practically all accepted Christianity; but all were tainted with the heresy of Arius. They could not conceive of our Lord as perfect God and perfect man, and they denied His divinity. Secondly, they assimilated as much as they could of the civilisation of the empire. Above all they were influenced to an extraordinary degree by Roman Law, so that they replaced to a great extent their old tribal customs by the law of the conquered; their greatest chieftains issued codes based on the Law of Rome.

Neither the conquered Romans nor their barbarian conquerors believed that the Roman Empire could really perish. ‘When Rome the head of the world shall have fallen,’ wrote Lactantius, ‘who can doubt that the end is come of human things, aye, of the earth itself?’ The Gothic chieftain’s aim was to become an official of the empire. Athaulf, the brother of Alaric, wrote, ‘When experience taught me that the untamable barbarism of the Goths could not suffer them to live beneath the sway of law, and the abolition of the institutions in which the state rested would involve the ruin of the state itself, I chose the glory of renewing and maintaining by Gothic strength the fame of Rome.’

Thus it was that in spite of the capture of Rome by Alaric in 410, it was not till the year 476 that the last Emperor of the West disappeared. In that year, by the advice of his barbarian supporters, the boy-emperor, Romulus, nicknamed Augustulus, surrendered to Zeno of Constantinople the title and insignia of the empire. The empire of the West became reabsorbed in that of the East, and Italy was ruled by Scyrrian and Ostrogothic kings bearing the title of Roman Patricians, nominally acknowledging the suzerainty of Constantinople.

Some sixty years later Justinian, the great Emperor of the East, made an effort to reconquer the lost possession of Italy; his generals, Belisarius and Narses, met with such success that for fifteen years the whole of Italy was regained. But in 568 a new swarm of invaders, the Lombards, came in from the north-east. Still, for the next two centuries Ravenna, Rome, Naples and Calabria remained a part of the empire.

Though the Lombard invasion thus checked the reestablishment of the empire in Italy, strange to say, it was one of the chief causes whereby the idea of the unity of Christendom was furthered. The pre-eminence of the Bishop of Rome dates from the moment of the decline of the western empire; there can be but little doubt that if, at the end of the seventh century, Italy had been definitely regained by the eastern empire, the history of the Papacy would have been very different from what it is. During the first three centuries of the Christian era the Patriarchs of Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Carthage were as important as, in fact more important than, the Bishop of Rome. At the time of the Council of Nicaea, and in the disputes which centred round the name of Athanasius, the Bishop of Rome was only beginning to stand out above his fellow Metropolitans. It was not the mythical donations of the dominion of the West to Sylvester I by Constantine the Great, but the strong action of Julius I in defending Athanasius, and the expelled bishops of Constantinople and Adrianople, against the semi-Arians, that definitely placed the Roman bishop at the head of the western churches; while the withdrawal of the seat of the empire of the West to Milan, Pavia or Ravenna, left the Bishop of Rome the greatest authority in the old Imperial City.

The action of the various popes, notably Leo I (440), in defending the city against the barbarians, added immensely to the prestige of the papal office. So much so that Leo protested against a decree of the Council of Chalcedon, which placed the see of Constantinople next to that of Rome—giving it pre-eminence over the sees of Antioch and Alexandria—on the ground that Rome was supreme and there could be no second to her. In this no doubt he was right, for Rome was busily engaged in winning the barbarians to the Christian faith, while Constantinople and the churches of the East were fully occupied with the subtle question as to the true nature of our Lord. Hence it was that, in spite of their Arianism, the many conquerors of the West regarded the Bishop of Rome as their spiritual head and the personification of the unity of Christendom. The bishops of Rome, from their jealousy of those of Constantinople, looked to the barbarian rulers of Italy, such as Odoacer and even Theodoric, for support, and acquiesced in their supervision of papal elections. It was thanks to the genius of Gregory I, who became bishop in 590, that Rome for long withstood the assaults of the Lombards. Without consulting the imperial exarch Gregory actually entered into treaties with the Lombard dukes; gradually, through his influence, the whole of the Lombard tribes became converted to the Christian faith. His missionary efforts were not confined to Italy, and we have to thank him for the introduction of Christianity into southern Britain by Augustine. It was also through his influence that Spain was won over to the Catholic faith and her king Reccared converted from Arianism. In spite of the many shortcomings of his successors, the Roman see never entirely lost the temporal and spiritual predominance that he had gained for it.

While the sixth century witnessed in Italy the phenomenon of the gradual extension of the spiritual and the temporal power of the Papacy, in the North a new dominion was springing up into existence, which, together with the Papacy, was to be the controlling influence in Europe for many centuries. The Franks were a section of the Teutonic race which, in the advance westwards, had settled part in Flanders, Artois and Picardy, and part along the banks of the Rhine from Mainz to Cologne and on the Moselle from Coblentz to Metz. The northern sections of this confederacy were known as the Salian, the southern as the Ripuarian Franks. In the year 481, Clovis, a petty king of the Salians, came to the throne of Tournai, and, after a reign of thirty years, gained for himself the sovereignty over all Franks, subduing to his rule three-fourths of France, the Rhine valley, and a great part of south-western Germany. By the year 535, his sons had actually established an overlordship of the Bavarians, and pushed their frontiers into Italy to the valley of the Adige. The Roman pontiff was glad to seek an ally in Clovis; for the Franks, the last invaders in the field, were not tainted by the heresy of Arianism. This alliance between the Frankish king and Roman bishop was to bear much fruit in the future.

But Clovis’ premature empire had within itself no latent strength; it depended not on organisation and law, but on the force and vitality of its rulers. The house of the Merovings, divided against itself and sapped by luxury and excess, was unable to bear the burden of empire after the second generation. Gradually its outlying possessions fell into the hands of their former rulers, provincials, like the Dukes of Aquitaine and Provence, or native Bavarian or Burgundian chiefs. Even Frankland became divided into what was known as Neustria, that is, Flanders, Champagne, Normandy and central France as far as the Loire, and Austrasia, the territory of the Rhine and the Moselle. Each division was ruled by a Meroving, the holder of Neustria usually claiming supremacy. Dagobert I, who died in 635, was the last of the race to display royal energy. After him they reigned, but did not govern; few lived beyond the age of twenty-five, and gradually all the royal authority fell into the hands of the chief officer called the ‘Mayor of the Palace.’ This official was the power behind the king as, in our own day, the shogun was the power behind the mikado, or the grand vizir the power behind the sultan. In Neustria the office did not become hereditary, being usually filled by one of the great nobles; but in Austrasia, about the year 615, there arose a Mayor of the Palace, whom we know as Pippin of Landen: his daughter married the son of his great friend St. Arnulf, Bishop of Metz.

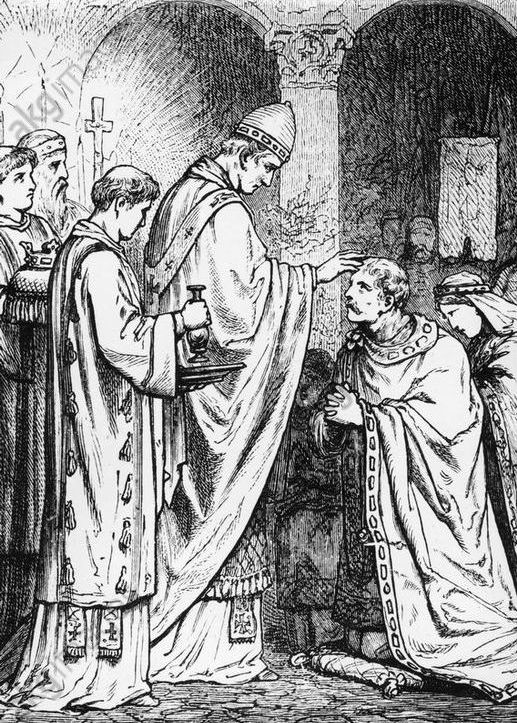

The Frankish history of the seventh and eighth centuries is but a record of how this family gradually made the office of Mayor of the Palace a hereditary possession. There was a futile attempt at usurping the kingship in 656, but it was almost a hundred years later that, in 750, the then Mayor of the Palace, another Pippin, deposed the last roi fainéant, and, with the authority of Pope Zacharias, proclaimed himself King of the Franks. As the Chronicle puts it, ‘Pope Zacharias therefore answered their (Pippin’s emissaries) question, that it seemed more expedient to him, that he should be called and be king, who had power in the kingdom, rather than he was was falsely called king. Therefore, the aforesaid pope commanded the king and people of the Franks, that Pippin, who exercised the royal power, should be called king and placed on the royal seat, which was accordingly done by the anointing of the holy Archbishop Boniface (the West Saxon) in the city of Soissons. Pippin is called king, and Childeric, who falsely bears that title, receives the tonsure and is sent into a monastery.’

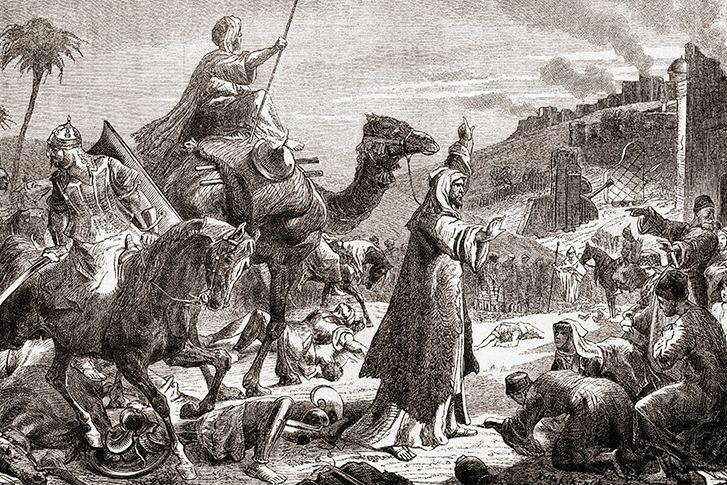

While, in the West, the important circumstance of the seventh century is the rise of the house of St. Arnulf to power among the Franks in alliance with the Papacy, in the East the emperor at Constantinople was faced by a religious convulsion, which shook the very foundations of his power. This phenomenon, even to the present day, is still to a great extent the dominating factor in the politics of Asia and northern Africa. The prophet of this new religion was Mohammed, the son of Abdullah, who preached to the northern tribes of Arabia a rigid Unitarian creed and a reformation of morals. At first the new prophet met with but little success. The year 622 saw his flight from Mecca, the famous ‘Hijrah,’ the event from which all Moslem history takes its date. But within ten years from the Hijrah Mohammed had converted all Arabia. His success was largely won by pandering to the habits and superstitions of his fellow tribesmen, hence a spirit of self-indulgence entered into his teaching which was fatal to its purity as a religion. Mohammed promised his followers in this world the goods of their enemies, and in the world to come a heaven of gross sensual enjoyment. He preached the extirpation of all unbelievers, and the sure possession of this voluptuous heaven by all killed in warfare against those whom he was pleased to term the infidels. The fatalism of the East, which was absorbed into Mohammedanism, supplied an invincible but short-lived driving power. Hence Islam became the religion of the warrior tribes of the East, and as an aggressive agent it stands unrivalled in the chronicles of the world. Scarcely had the prophet died when, in 633, his successor, Abu Bekr, led forth from the wilds of Arabia two armies to conquer Persia for Islam. With the cry from their leaders ‘Paradise is before you, the devil and hell fire behind you,’ the Moslem fanatics overthrew the army of the eastern empire at Hieromax (Yermak) in the summer of 634. By 640 they had conquered all Syria, and threatening Asia Minor were crossing the desert of Suez to invade Egypt. Pushing along the southern shore of the Mediterranean they subdued all northern Africa, and crossing to Spain, in the year 711, they so completely overwhelmed the Visigothic kingdom, that practically nothing is known of the last hundred years of its existence. By 713, the Moslems were rulers of the whole of Spain, except along the mountainous coast of the Bay of Biscay, where the Basques and the Visigothic highlanders of Asturias retained a precarious liberty.

It seemed for a time as if western Europe was to fall before the Moslems. By 720, they had subdued the province of Narbonne or Septimannia, and, in 725, the penetrated as far as Autun, in the heart of Burgundy. What was more ominous, they found an ally in Eudo, the provincial Duke of Aquitaine. But the sword of Charles Martel, the father of King Pippin, and the treachery of the Moslems, taught Duke Eudo the foolishness of such an alliance. In the year 732, Abderahman, the great Moslem leader, started from Pampeluna with a vast host, bent on the conquest of Gaul. Sweeping aside the Aquitainians and their duke, he completely overcame that province and penetrated as far north as Poictiers. But there he found, covering the only passage between the lower spurs of the Auvergne Mountains and the Bocage, the might of the Franks under the great Mayor of the Palace, Karl, or, as he is otherwise known, Charles Martel, ‘the hammer.’ The great struggle followed which was to decide whether the Koran or the Gospel was to be the religion of the West. For seven days the hosts of Mohammed and Christ faced each other; the issue was so uncertain that the leaders on either side were almost afraid to take the initiative. At last Abderahman set his troops in motion, and the fiery Moslems hurled themselves against the masses of Frankish infantry. Of the details of the fight we know nothing; the Spanish chronicler Isidore is our only guide. ‘The northern natives,’ he tells us, ‘stood immovable as a wall or as if frozen to their places by the rigorous weather of winter, but hewing down the Arabs with their swords. But when the Austrasian people, by the might of their massive limbs, and with iron hands striking straight from the chests their strenuous blows, had laid multitudes of the enemy low, at last they found the king (Abderahman) and robbed him of life. Then night separated the combatants, the Franks brandishing their swords on high in scorn of the enemy.’ The remnants of the Moslem hosts fled in disorder, and so ended the danger to western Christendom from the followers of the prophet. The next important event in the eighth century in the drama of western Europe was the final disappearance of the power of the eastern emperor from Italy, and the consequent complete emancipation of the Bishop of Rome.

We must return for a short period to the eastern empire. In 634, the fatal weakness of the empire was proved at the battle of Hieromax. But it was not till 717, that after varying fortune the Moslems, after ravaging Phyrgia and Cappadocia, threatened the heart of the eastern empire. Fortunately, in that year, out of the throes of revolution, there appeared a soldier capable of mastering the situation. Leo, the Isaurian, seized the Imperial Crown from his incompetent master Theodosius III; and when a few months later, for the second time, the Moslem fleet and armies appeared before Constantinople, they again found an opposition worthy of the Roman name. After the vicissitudes of a siege lasting a full year the enemy fell back exhausted. It was primarily, no doubt, thanks to the impregnable walls of Constantinople and to Greek fire that the leaguer failed; but without the courage, energy and skill of Leo, mere fortifications would have availed but little. The successful defence of Constantinople was, in its way, no less important for Europe than the battle of Poictiers. The Mohammedan power had received a complete set back, and for the next five centuries Europe had little to fear on her eastern flank; in fact, Leo’s successors regained a great deal of their lost Asiatic possessions owing to divisions in the Mohammedan camp.

To return now to the relations between Constantinople and the Papacy. For fifty years after the death of Pope Gregory I there was a period of comparative agreement. But in 655 Constans II, finding his decrees on the Monothelite heresy treated with disdain by the fiery Pope Martin, seizing a favourable opportunity had the contumacious Martin carried off in chains to the Crimea. This did much to estrange the loyalty of the Romans. In 663, Constans actually paid a visit to Italy, and, finding the Romans disloyal, attempted to neutralise the power of the Roman Church by granting to the Archbishop of Ravenna a formal exemption from spiritual obedience to the Bishop of Rome. Constans’ son, Constantine V, reversed this policy. Indeed, in 681, he even went so far as to announce, that, if the suffrage of the clergy, people and soldiery of Rome were unanimously cast for one candidate that man might at once be consecrated pope without awaiting an imperial mandate from Constantinople.

During the twenty years of anarchy preceding the reign of Leo the Isaurian, the popes John II and Gregory II levied taxes, made treaties, and accepted or refused to acknowledge the mushroom emperors. So independent had they become that when, in 726, Leo the Isaurian issued the famous edict, forbidding the worship of statues and paintings, Gregory II treated this decree with contumacy, telling him that he was little better than an ignorant school-boy. It was thanks to the power of the great Lombard king, Liutprand, that the rebellious pope escaped the arm of the exarch who was sent by the emperor to punish him. But, in 740, his successor Gregory III quarrelled with Liutprand, who was now, to all intents, the ruler of Italy. The pope could not hope for any help from the emperor whom he had so lately insulted. Accordingly, in his extremity he turned to Charles Martel, and as a bribe invested him with the title of Roman Patrician, which title was not his to give. He sent him also the golden keys of the tomb of St. Peter. Charles refused to quarrel with Liutprand, who had helped him against the Moslems at Poictiers and elsewhere. So in the end the pope was forced to make terms with Liutprand. The diplomacy of Pope Gregory III has vast significance, because it foreshadows the temporary alliance between the ruler of the Franks and the Bishop of Rome, which, sixty years later, re-established the Roman Empire of the West, and led to the supremacy of the Papacy.

It was, as we have already said, ten years later, in 750, that the descendant of St. Arnulf at last, with the connivance of the pope, deposed the Merovings, and stood forth as ruler of the Franks in name as well as in fact. There were many reasons for the sanction thus given by the Papacy. The house of Arnulf had, all through its history, lent a willing hand to the famous band of missionaries who, during the eighth century, were so active in converting the heathen to the east of the Rhine, Saxons, Frisians and Wends. These missionary bishops were most zealous upholders of the spiritual domination of the Bishop of Rome. It was therefore only meet that the greatest of them, Boniface, an Englishman from Crediton, should be selected by the pope to crown King Pippin. By way of adding sanctity to the ceremony, Boniface anointed him, like David, with holy oil. Another great reason for the papal action was the fear of the Lombards. Having got rid of the authority of the absentee emperor, the pope had no desire to fall under the influence of the ever present rulers of Pavia, who were now attempting to exercise the forgotten rights of the emperor over Rome and its church.

Very soon the pope called upon the gratitude of the new king. Early in January 754, Stephen II arrived at Ponthieu at Pippin’s court, demanding vengeance on the Lombards, who, he declared, were attempting to spoil St. Peter of his patrimony. Some time was spent in negotiations, during which, at St. Denis, the pope ‘anointed the most pious Prince Pippin, King of the Franks, with the oil of holy anointing, according to the custom of the ancients, and at the same time crowned his two sons, who stood next to him, in happy succession, Charles and Carloman, with the same honors.’

Charles or Karl, better known as Charlemagne, is the first of our portraits, and with him we will begin a new chapter, but before closing this one we will take a rapid glance at the map of Europe, in the year 754. The whole of the Iberian peninsula, save Tras os Montes and Asturias (i.e. the northern slopes of the Cantabrian Mountains) had fallen beneath the yoke of the Saracens. The old kingdom of Septimannia between the Pyrenees and the Rhone, and the duchy of Aquitaine, might any day be invaded by them.

The Frankish kingdom extended over all modern France and included Frisia: the boundary then ran south down the Rhine, until it diverged east along the Taunus as far as the Harz Mountains, then down the Saale to the Bohemian Wald, including Bavaria as far as the river Inn. But though the limits were thus great, the Frankish kingdom was by no means homogeneous, and might at any moment split up along old tribal lines.

In Italy the Lombards held the valley of the Po, Tuscany, and the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. Diagonally across the Lombard states ran the remains of the old exarchate, till lately subordinate to the empire of the East. It included the strip of territory on the east of the Appenines from the mouth of the Po to Ancona, and Rome, Naples, Salerno, and most of Apulia. Calabria and Sicily still owned allegiance to Constantinople.

Central Europe, save for the Teutonic tribe of Saxons, whose lands stretched from the Harz Mountains to the Oder, was inhabited by Slavic tribes, Serbs, Czechs, Wends and Croats, and Mongolian Avars.

Fascinating. I will have to look into this author and his book. Thanks for bringing it to my attention.